Fort Myers: An Alternative History

Located on the eastern face of the federal courthouse in the downtown Fort Myers River District is a 20 foot tall by 100 foot long ceramic tile mural. Dominating a brick paved courtyard that the federal building shares with Hotel Indigo and Starbucks, the sepia-toned mural depicts Chief Billy Bowlegs, a section of stockade of the old fort

Located on the eastern face of the federal courthouse in the downtown Fort Myers River District is a 20 foot tall by 100 foot long ceramic tile mural. Dominating a brick paved courtyard that the federal building shares with Hotel Indigo and Starbucks, the sepia-toned mural depicts Chief Billy Bowlegs, a section of stockade of the old fort  for which the city is named, a contingent of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops that defended the fort from Confederate attack in the waning days of the Civil War, a cattle rancher leaning against one of his steers and the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad locomotive that brought rail

for which the city is named, a contingent of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops that defended the fort from Confederate attack in the waning days of the Civil War, a cattle rancher leaning against one of his steers and the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad locomotive that brought rail  service to the fledgling town on February 20, 1904. Named Fort Myers: An Alternative History, this 1999 public art installation by public artist and photography professor Barbara Jo Revelle encapsulates Fort Myers’ early history, a 46-year period denoted by conflict, struggle, and even abject shame.

service to the fledgling town on February 20, 1904. Named Fort Myers: An Alternative History, this 1999 public art installation by public artist and photography professor Barbara Jo Revelle encapsulates Fort Myers’ early history, a 46-year period denoted by conflict, struggle, and even abject shame.

Where it is

The mural overlooks a courtyard that is shared by the federal courthouse on the west, Hotel Indigo to the south and Starbucks Coffee to the east. You can access the courtyard either by going through the arcade leading past Vino de Notte and Icheban restaurant to Hotel Indigo or via the entrance on First Street. [The mural’s physical address is 2167 First Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901. It sits at Latitude N 26° 37′ 13.4381″ and Longitude W 81° 52′ 20.9912″.]

The mural overlooks a courtyard that is shared by the federal courthouse on the west, Hotel Indigo to the south and Starbucks Coffee to the east. You can access the courtyard either by going through the arcade leading past Vino de Notte and Icheban restaurant to Hotel Indigo or via the entrance on First Street. [The mural’s physical address is 2167 First Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901. It sits at Latitude N 26° 37′ 13.4381″ and Longitude W 81° 52′ 20.9912″.]

What it Depicts

In choosing the subject matter for this mural,” states Barbara Jo Revelle, “I wanted to represent an alternative history of Fort Myers, not the official one we are accustomed to, the one featuring Thomas Edison, the electrical wizard who for nearly half a century was a winter resident of Fort Myers.” Revelle felt with good cause that Edison and his story, as well as that of his friend and

In choosing the subject matter for this mural,” states Barbara Jo Revelle, “I wanted to represent an alternative history of Fort Myers, not the official one we are accustomed to, the one featuring Thomas Edison, the electrical wizard who for nearly half a century was a winter resident of Fort Myers.” Revelle felt with good cause that Edison and his story, as well as that of his friend and  fellow inventor Henry Ford, were characterized adequately in various ways and pieces throughout the community. “In this mural, I wanted to represent some of the lesser known (and perhaps even suppressed) chapters in Fort Myers history, some of the events associated with the actual Fort Myers fort.”

fellow inventor Henry Ford, were characterized adequately in various ways and pieces throughout the community. “In this mural, I wanted to represent some of the lesser known (and perhaps even suppressed) chapters in Fort Myers history, some of the events associated with the actual Fort Myers fort.”

The ignominy of the United States’ deportation of  the bedraggled remnants of Seminole nation to reservations in Oklahoma, the fact that Fort Myers was a Union stronghold during the Civil War, the role played by black soldiers in depriving the Confederacy of much needed beef and defending the fort from Confederate attack on February 20, 1865, Fort Myers’ role as a cow town in the last half of the 19th century and the city’s struggles to bring rail service to the town are “crucial in any attempt to characterize Fort Myers’ real history,” Revelle contends. And that represents the guide to appreciating the images Revelle used as content for Fort Myers: An Alternative History.

the bedraggled remnants of Seminole nation to reservations in Oklahoma, the fact that Fort Myers was a Union stronghold during the Civil War, the role played by black soldiers in depriving the Confederacy of much needed beef and defending the fort from Confederate attack on February 20, 1865, Fort Myers’ role as a cow town in the last half of the 19th century and the city’s struggles to bring rail service to the town are “crucial in any attempt to characterize Fort Myers’ real history,” Revelle contends. And that represents the guide to appreciating the images Revelle used as content for Fort Myers: An Alternative History.

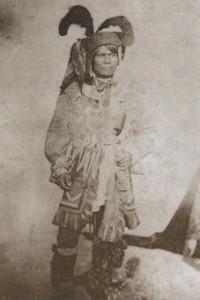

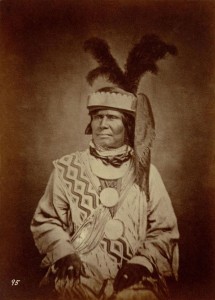

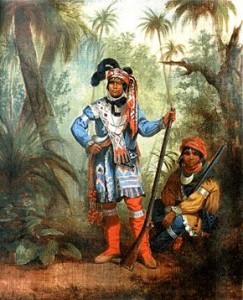

Chief Billy Bowlegs, his tribe and the Steamer Grey Cloud

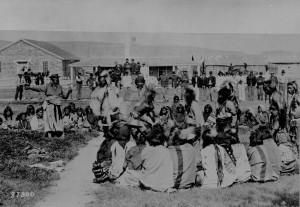

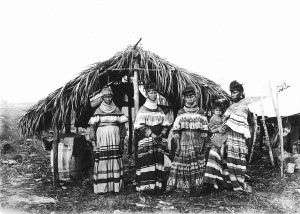

The left (south) quadrant of the mural depicts a contingent of Seminole Indians standing on the shore of the Caloosahatchee River next to Chief Billy Bowlegs with the steamer Grey Cloud in the background. According to the muralist, Barbara Jo Revelle, this vignette represents “one of the darkest chapters in Fort Myers’ history” and

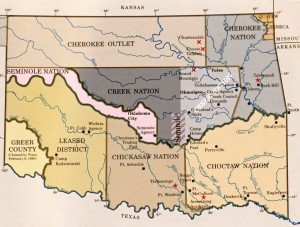

The left (south) quadrant of the mural depicts a contingent of Seminole Indians standing on the shore of the Caloosahatchee River next to Chief Billy Bowlegs with the steamer Grey Cloud in the background. According to the muralist, Barbara Jo Revelle, this vignette represents “one of the darkest chapters in Fort Myers’ history” and  depicts the sad conclusion to the Seminole wars, during which the Seminole people, “including elders, women and children, were hunted with bloodhounds, rounded up like cattle, and forced onto ships that carried them to New Orleans,” up the Mississippi and ultimately to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma and Arkansas “where they were attacked by other tribes in a fierce competition for the scarce resources they all needed to survive.”

depicts the sad conclusion to the Seminole wars, during which the Seminole people, “including elders, women and children, were hunted with bloodhounds, rounded up like cattle, and forced onto ships that carried them to New Orleans,” up the Mississippi and ultimately to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma and Arkansas “where they were attacked by other tribes in a fierce competition for the scarce resources they all needed to survive.”

Billy Bowlegs’ life can be viewed as a metaphor for the plight of all the Indians who migrated to Florida in the first third of the 19th century. For the Yemassee, Choctaw, Yuchi, Mikasuki and the Seminoles who came from the north and west, Florida was home. They loved the land  and could see no reason why they would ever want to give up their fields, forests and fishing for the arid lands in Arkansas and Oklahoma. But wealthy slave owners wanted the lands they occupied in and around Lake Okeechobee for sugar cane and rice plantations, and they lobbied Washington and whipped up local sentiment for deporting the Indians from the territory. When the army and white settlers inevitably tried squeezing them out, they defended the lands they’d been promised even though it was clear from the outset that they were vastly outnumbered and out-gunned.

and could see no reason why they would ever want to give up their fields, forests and fishing for the arid lands in Arkansas and Oklahoma. But wealthy slave owners wanted the lands they occupied in and around Lake Okeechobee for sugar cane and rice plantations, and they lobbied Washington and whipped up local sentiment for deporting the Indians from the territory. When the army and white settlers inevitably tried squeezing them out, they defended the lands they’d been promised even though it was clear from the outset that they were vastly outnumbered and out-gunned.

The Second Seminole War started in 1836. It didn’t go well for the Indians, and by the end of 1838, the Army had rounded up and  deported more than 2,000 Indian men, women and children. So when Major General Alexander Macomb offered a new peace treaty in May of 1839, the remaining tribes had little choice but to meet with the commander-in-chief of the American Army. They were lead by Chitto-Tustenugger, principal chief of the Seminoles. Chief Billy Bowlegs was also a member of the council.

deported more than 2,000 Indian men, women and children. So when Major General Alexander Macomb offered a new peace treaty in May of 1839, the remaining tribes had little choice but to meet with the commander-in-chief of the American Army. They were lead by Chitto-Tustenugger, principal chief of the Seminoles. Chief Billy Bowlegs was also a member of the council.

General Macomb promised the Indians a tract of land that stretched south from Charlotte Harbor and the Peace River and east from the center of Lake Okeechobee and the Shark River  west to the Gulf. (This was practically all of what is now Lee County and major portions of Charlotte, Glades, Hendry and Collier counties.) But while Macomb led the Indians to believe that these lands would be theirs forever, he only meant for the arrangement to be a delaying tactic aimed at giving him time to reinforce his positions in and surrounding Indian territory.

west to the Gulf. (This was practically all of what is now Lee County and major portions of Charlotte, Glades, Hendry and Collier counties.) But while Macomb led the Indians to believe that these lands would be theirs forever, he only meant for the arrangement to be a delaying tactic aimed at giving him time to reinforce his positions in and surrounding Indian territory.

When the Indians discovered Macomb’s deception, they were furious. A war council was convened involving leaders of every tribe remaining in Florida. Afterwards, Bowlegs led an attack against a trading outpost that was being built by the Army on the north bank of the Caloosahatchee about nine miles down river from the present site of Fort Myers. Told  that Indians coming to the post were to be detained and deported, two hundred warriors led by Bowlegs and two Spanish Indian chiefs (who represented the last remnants of the mighty Calusa nation that once rule the southern half of Florida from their capital on Mound Key in Estero Bay) attacked the fort, killing 18 soldiers, a trader and his two clerks.

that Indians coming to the post were to be detained and deported, two hundred warriors led by Bowlegs and two Spanish Indian chiefs (who represented the last remnants of the mighty Calusa nation that once rule the southern half of Florida from their capital on Mound Key in Estero Bay) attacked the fort, killing 18 soldiers, a trader and his two clerks.

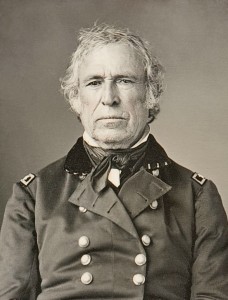

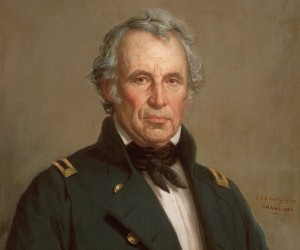

Of course, white settlers insisted that the massacre be avenged, and this duty was assigned to a brigadier general by the name of Zachary Taylor. As part of his campaign against the Indians, he re-established Fort Dulany (as well as Forts Denaud and Thompson further up river) and harried the Seminoles and their  allies in every possible way. As muralist Barbara Jo Revelle notes in her Guidebook, Taylor even purchased 33 bloodhounds from Cuba (at a cost of $151.72 each), but the dogs were trained to hunt for escaped slaves and would not follow the scent of the Indians, leaving Taylor the butt of criticism and derisive jokes.

allies in every possible way. As muralist Barbara Jo Revelle notes in her Guidebook, Taylor even purchased 33 bloodhounds from Cuba (at a cost of $151.72 each), but the dogs were trained to hunt for escaped slaves and would not follow the scent of the Indians, leaving Taylor the butt of criticism and derisive jokes.

While Taylor’s experiment with bloodhounds may have proved unsuccessful, the rest of his campaign  was highly effective. Spanish Indian Chief Chekika and five of his warriors were captured and hung in 1840 and the following November, Chief Coacoochee, the most brilliant Indian leader since Osceola, was deported west with 300 of his people. In February of 1842, 230 more Indians of various tribes were shipped out as well. In all, 3,930 Indians were deported to Arkansas and Oklahoma and hundreds more died in battle or from starvation and disease. Less than 600 Indians remained in all of Florida. But the cost of removing the Indians had been exorbitantly high. The seven year war cost the U.S. government more than $40 million and the lives of 1,466 soldiers.

was highly effective. Spanish Indian Chief Chekika and five of his warriors were captured and hung in 1840 and the following November, Chief Coacoochee, the most brilliant Indian leader since Osceola, was deported west with 300 of his people. In February of 1842, 230 more Indians of various tribes were shipped out as well. In all, 3,930 Indians were deported to Arkansas and Oklahoma and hundreds more died in battle or from starvation and disease. Less than 600 Indians remained in all of Florida. But the cost of removing the Indians had been exorbitantly high. The seven year war cost the U.S. government more than $40 million and the lives of 1,466 soldiers.

By the time the Army extended a new offer of peace, the only chief of any significance still remaining was Billy Bowlegs. He adamantly refused to be deported west. After lengthy talks, the war-weary government agreed to let Billy and the few remaining Indians live in peace on the very lands they’d been promised by General Macomb in 1939.

By the time the Army extended a new offer of peace, the only chief of any significance still remaining was Billy Bowlegs. He adamantly refused to be deported west. After lengthy talks, the war-weary government agreed to let Billy and the few remaining Indians live in peace on the very lands they’d been promised by General Macomb in 1939.

With this as backdrop, one can only imagine what went through Billy Bowlegs’ mind when he got word in 1850 that a new fort was being established on the banks of the Caloosahatchee, nine miles up river from the site of the 1839 trading post massacre. But Bowlegs did not attack the new  fort. Instead, he made a trip there to speak to the major who was building it and told the major that he and his people “were satisfied with their new homes [in the Big Cypress], and wanted nothing more than to be left alone.” But the slave owners in the northern part of Florida still dreamed of converting the Everglades into lucrative sugar cane and rice plantations, and they continued to lobby the federal government for removal of the remaining Indians. In 1851, the federal

fort. Instead, he made a trip there to speak to the major who was building it and told the major that he and his people “were satisfied with their new homes [in the Big Cypress], and wanted nothing more than to be left alone.” But the slave owners in the northern part of Florida still dreamed of converting the Everglades into lucrative sugar cane and rice plantations, and they continued to lobby the federal government for removal of the remaining Indians. In 1851, the federal  government acceded to their demands.

government acceded to their demands.

At their insistence, steps were taken to persuade Billy and his people to leave the state. In fact, Chief Bowlegs and three of his people accompanied an Indian agent by the name of Luther Blake to Washington in 1851 to meet with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and they even signed an agreement consenting to be relocated. But nothing came of it after Bowlegs returned to Florida. So two years later, the federal government upped the ante.

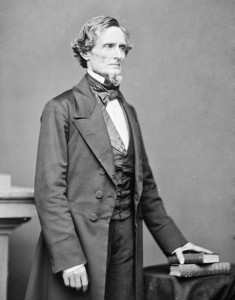

On May 3, 1854, Blakes’ replacement, Captain John C. Casey, presented a two-prong plan to U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who openly  sympathized with the “Indian hating” plantation owners who wanted to put 100,000 slaves to work in the deep, rich muckland around Lake Okeechobee planting, cultivating and harvesting sugar cane and rice (“but not with the Seminoles living on the edge of the Everglades in that precious muckland”). First, all Florida trading posts were to be immediately closed to the Indians in order to cut off their access to supplies, provisions and most of all, ammunition. Second, scouting parties would systematically encroach on Indian lands to let the Indians know that civilization was advancing and settlers were on the way. Of course, the ultimate goal of Casey’s plan was to goad the Indians into a new war.

sympathized with the “Indian hating” plantation owners who wanted to put 100,000 slaves to work in the deep, rich muckland around Lake Okeechobee planting, cultivating and harvesting sugar cane and rice (“but not with the Seminoles living on the edge of the Everglades in that precious muckland”). First, all Florida trading posts were to be immediately closed to the Indians in order to cut off their access to supplies, provisions and most of all, ammunition. Second, scouting parties would systematically encroach on Indian lands to let the Indians know that civilization was advancing and settlers were on the way. Of course, the ultimate goal of Casey’s plan was to goad the Indians into a new war.

In 1855, the War Department’s topographical engineers were ordered to begin making surveys in Indian Territory, and on December 7, 1855, Lt. George Hartsuff and a survey party were dispatched from the fort to the Big Cypress to find out where the Seminoles were living. Historians believe that Hartsuff provoked an incident in order to create support for rounding up the Seminoles. According to historian Karl H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers, on December 19 Hartsuff’s men “trampled down [Chief Bowlegs’] banana stalks, smashed the pumpkins growing nearby and uprooted [his] potatoes. Soon afterward, Billy returned. He was

In 1855, the War Department’s topographical engineers were ordered to begin making surveys in Indian Territory, and on December 7, 1855, Lt. George Hartsuff and a survey party were dispatched from the fort to the Big Cypress to find out where the Seminoles were living. Historians believe that Hartsuff provoked an incident in order to create support for rounding up the Seminoles. According to historian Karl H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers, on December 19 Hartsuff’s men “trampled down [Chief Bowlegs’] banana stalks, smashed the pumpkins growing nearby and uprooted [his] potatoes. Soon afterward, Billy returned. He was  enraged. And when he demanded compensation, Hartsuff’s men laughed uproariously. They tripped Billy and sent him sprawling. When he arose, his face was covered with dirt. Seething with anger, Billy left.”

enraged. And when he demanded compensation, Hartsuff’s men laughed uproariously. They tripped Billy and sent him sprawling. When he arose, his face was covered with dirt. Seething with anger, Billy left.”

Hartsuff underestimated the swiftness of Bowlegs’ reprisals. At daybreak on the morning of December 20, Bowlegs and a small band of Seminoles attacked Hartsuff’s camp. Two surveyors were killed and Hartsuff and three more of his men were wounded before they repelled the attack and retreated back to Fort Myers. Grismer maintains that while the destruction of Bowlegs’ garden may have been the spark that set off the  powder keg, it was only a matter of time before the Seminoles went on the warpath because of the effects of Casey’s plan. But even so, there was limited damage they could do as there were less than 600 Seminoles left in the entire State of Florida by that time. “And that number included women and children, cripples and men too old to fight.

powder keg, it was only a matter of time before the Seminoles went on the warpath because of the effects of Casey’s plan. But even so, there was limited damage they could do as there were less than 600 Seminoles left in the entire State of Florida by that time. “And that number included women and children, cripples and men too old to fight.  The number of warriors did not exceed one hundred and fifty.”

The number of warriors did not exceed one hundred and fifty.”

For more than two years, Bowlegs and his warriors engaged in a campaign of guerrilla warfare. They ambushed the soldiers by day and attacked them  under cover of darkness at night before slipping back into the impenetrable swamps in the Big Cypress. “Women and children, and men too old to fight, were sent deep into the Big Cypress to secret places where no white men had ever gone.” This time, human bloodhounds were used. Induced by a reward of $500 for each captured warrior and $100 for women and children, three companies of Florida volunteers were formed to track the Indians to their secret lairs, burn their homes, destroy their crops, kill those who resisted and capture those didn’t. But in all of 1857, only 30 Seminoles were rounded up. They were interred at the federal stockade on Egmont Key in the mouth of Tampa Bay.

under cover of darkness at night before slipping back into the impenetrable swamps in the Big Cypress. “Women and children, and men too old to fight, were sent deep into the Big Cypress to secret places where no white men had ever gone.” This time, human bloodhounds were used. Induced by a reward of $500 for each captured warrior and $100 for women and children, three companies of Florida volunteers were formed to track the Indians to their secret lairs, burn their homes, destroy their crops, kill those who resisted and capture those didn’t. But in all of 1857, only 30 Seminoles were rounded up. They were interred at the federal stockade on Egmont Key in the mouth of Tampa Bay.

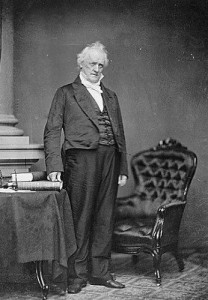

Prompted by this lack of progress, President James Buchanan issued orders to renew efforts to remove the remaining Seminoles by peaceful means. One of the reasons Bowlegs was reluctant to relocate his people was because the Seminoles and their sworn enemies the Creeks had been forced to live on the same reservation in Arkansas. Now, they were given separate tracts as well as cash settlements, some of which was contingent upon them persuading Bowlegs and his people to leave Florida. Toward this end, 40 Seminoles and six Creeks accompanied Arkansas Superintendent of Indian Affairs Colonel Elias Rector to Fort Myers in February of 1858. Bowlegs agreed to meet them, and came under truce to the fort on March 4.

Prompted by this lack of progress, President James Buchanan issued orders to renew efforts to remove the remaining Seminoles by peaceful means. One of the reasons Bowlegs was reluctant to relocate his people was because the Seminoles and their sworn enemies the Creeks had been forced to live on the same reservation in Arkansas. Now, they were given separate tracts as well as cash settlements, some of which was contingent upon them persuading Bowlegs and his people to leave Florida. Toward this end, 40 Seminoles and six Creeks accompanied Arkansas Superintendent of Indian Affairs Colonel Elias Rector to Fort Myers in February of 1858. Bowlegs agreed to meet them, and came under truce to the fort on March 4.

“A shrewd bargainer,” reports muralist Revelle, “Billy Bowlegs received $7,500 for himself and generous amounts for his tribe.” (Grismer breaks down the amount as $5,000 for Bowlegs, $2,500 for the cattle that had been stolen from him by the soldiers at the fort, $1,000 for each warrior and $100 for each woman and child.) He also received assurances that he and his tribe would be settled on land apart from the Creeks living in the

“A shrewd bargainer,” reports muralist Revelle, “Billy Bowlegs received $7,500 for himself and generous amounts for his tribe.” (Grismer breaks down the amount as $5,000 for Bowlegs, $2,500 for the cattle that had been stolen from him by the soldiers at the fort, $1,000 for each warrior and $100 for each woman and child.) He also received assurances that he and his tribe would be settled on land apart from the Creeks living in the  resettlement area. The deal struck, small groups of Indians began arriving at the fort toward the end of March. They set up camp on a creek about a mile north of the fort close to where the Fort Myers Cemetery is located today. Because this was the spot where Billy’s people surrendered, the creek has ever after been called Billy’s Creek, writes Grismer.

resettlement area. The deal struck, small groups of Indians began arriving at the fort toward the end of March. They set up camp on a creek about a mile north of the fort close to where the Fort Myers Cemetery is located today. Because this was the spot where Billy’s people surrendered, the creek has ever after been called Billy’s Creek, writes Grismer.

By May 1, a total of 124 warriors,women, children and elders had gathered in the camp. On May 4, 1858, they boarded the steamer Grey Cloud bound for New Orleans and ultimately the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. En route, the Grey Cloud stopped at Egmont Key, where the 41 Indians captured by federal troops and Florida volunteers were  taken aboard. Regrettably, Bowlegs did not have the opportunity to enjoy much of the relocation money he and his tribe received. He died on April 27, 1859, shortly after reaching the lands set aside for him and his tribe in Oklahoma. Unfortunately for him, Oklahoma was in the throes of a small pox epidemic, and the Seminole Chief contracted and succumbed to the scourge that killed tens of thousands of Native Americans between 1837 and 1870.

taken aboard. Regrettably, Bowlegs did not have the opportunity to enjoy much of the relocation money he and his tribe received. He died on April 27, 1859, shortly after reaching the lands set aside for him and his tribe in Oklahoma. Unfortunately for him, Oklahoma was in the throes of a small pox epidemic, and the Seminole Chief contracted and succumbed to the scourge that killed tens of thousands of Native Americans between 1837 and 1870.

Although the fort was abandoned that June, Arkansas Superintendent of Indian Affairs Elias Rector returned the following January and persuaded 70 more Seminoles to leave. They were the last group of Indians to be deported from the state. “The others [about 300] were allowed to stay. “Those who remained behind were the undefeated,” sums up Grismer. “But now they did

Although the fort was abandoned that June, Arkansas Superintendent of Indian Affairs Elias Rector returned the following January and persuaded 70 more Seminoles to leave. They were the last group of Indians to be deported from the state. “The others [about 300] were allowed to stay. “Those who remained behind were the undefeated,” sums up Grismer. “But now they did  not possess an acre they could call their own. They had no rights as citizens; legally they were trespassers on others’ land. Not until 1917 …. did the State of Florida set aside 100,000 acres for them as a reservation – 100,000 acres of swamp, and sawgrass, and wilderness.”

not possess an acre they could call their own. They had no rights as citizens; legally they were trespassers on others’ land. Not until 1917 …. did the State of Florida set aside 100,000 acres for them as a reservation – 100,000 acres of swamp, and sawgrass, and wilderness.”

It is small wonder that muralist Barbara Jo Revelle calls this “one of the darkest chapters in Fort Myers’ history.”

* * * * *

The fort on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River

“One important function public art can serve is to help us remember the lived history of a particular site,” writes Barbara Jo Revelle. “[T]he site of the Federal Building and Court House is actually on the land formerly occupied by the old fort.”

“One important function public art can serve is to help us remember the lived history of a particular site,” writes Barbara Jo Revelle. “[T]he site of the Federal Building and Court House is actually on the land formerly occupied by the old fort.”

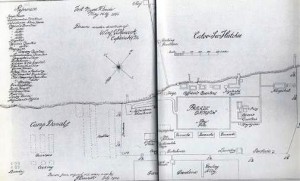

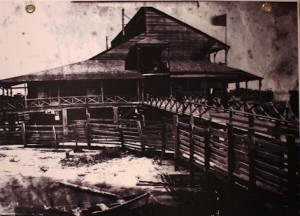

Actually, the fort depicted in Revelle’s mural was massive. Although sources disagree on the fort’s size and dimensions, those based on the links-based survey of the fort conducted in 1856 (and filed of record in the Federal Register) suggest that the fort’s wooden stockade ran from just east of Broadway to just east of Royal Palm,  and from Main Street on the south to the river bank, which meandered along what is Bay Street today.

and from Main Street on the south to the river bank, which meandered along what is Bay Street today.

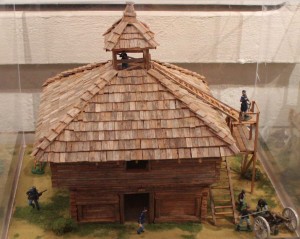

It consisted of as many as three dozen hewn pine buildings which included officers’ quarters (running along the area now occupied by the Arcade and the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center),  barracks, administration offices, a 2½-story hospital with plastered rooms, warehouses for the storage of munitions and general supplies, a guard house (see model at Southwest Florida Museum of History, below right), blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a kitchen, bakery, laundry, a sutler’s store, stables for horses and mules, a gardener’s shack, and even a bowling alley and bathing pier and pavilion.

barracks, administration offices, a 2½-story hospital with plastered rooms, warehouses for the storage of munitions and general supplies, a guard house (see model at Southwest Florida Museum of History, below right), blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a kitchen, bakery, laundry, a sutler’s store, stables for horses and mules, a gardener’s shack, and even a bowling alley and bathing pier and pavilion.

It also boasted a pier nearly 700 feet long that had a  wide dock and rails that enabled the soldiers to bring in supplies by tram without having to lighter them ashore. The buildings were sided and topped by cedar shingles shipped in from Pensacola and Apalachicola, together with doors, windows and flooring. The interior featured parade grounds, a

wide dock and rails that enabled the soldiers to bring in supplies by tram without having to lighter them ashore. The buildings were sided and topped by cedar shingles shipped in from Pensacola and Apalachicola, together with doors, windows and flooring. The interior featured parade grounds, a  carefully-tended velvety lawn, two immense vegetable gardens, rock-rimmed river banks, shell walks, lush palms and even citrus trees.

carefully-tended velvety lawn, two immense vegetable gardens, rock-rimmed river banks, shell walks, lush palms and even citrus trees.

The fort replaced a small outpost named Fort Harvie that was built in November of 1841 after Fort Dulany, built some 15 miles downriver at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River, was washed away in a hurricane. Fort Harvie’s tenure was destined to be short-lived. It was abandoned just  four months later on March 21, 1842 when the Second Seminole War came to an end. But after five Indians killed a trader by the name of Whidden toward the end of the decade, the United States Secretary of War ordered a new fort built for the purpose of rounding up the few Seminoles remaining in southwest Florida.

four months later on March 21, 1842 when the Second Seminole War came to an end. But after five Indians killed a trader by the name of Whidden toward the end of the decade, the United States Secretary of War ordered a new fort built for the purpose of rounding up the few Seminoles remaining in southwest Florida.

“[Major] General [David] Emanuel Twiggs signed the order for the new fort on February 14, 1850,” reports Barbara Jo Revelle in her Guidebook on the mural. “A week later, Major Ridgely of the 4th Artillery sailed up the Caloosahatchee, spotted the clearing where Fort Harvie stood eight years previously, and landed.” The date was February 20, 1850. “Fort Myers was born.”

Fort Harvie had been almost completely destroyed by fires. “Probably set by revengeful Indians,” speculates historian Karl H. Grismer. So Ridgely and his men had to rebuild the post, which was renamed Fort Myers in honor of Colonel Abraham C. Myers, who was soon to wed General Twigg’s daughter. Myers was the chief quartermaster of Florida at the time, and although there is no record of him ever visiting his namesake, all buildings had to be constructed in accordance with plans he alone approved. With nearly unlimited funds, the fort became one of the finest, if not the most expensive, in the country. “So much government money was spent on the fort during the 1850s that the War Department ordered an investigation.”

Fort Harvie had been almost completely destroyed by fires. “Probably set by revengeful Indians,” speculates historian Karl H. Grismer. So Ridgely and his men had to rebuild the post, which was renamed Fort Myers in honor of Colonel Abraham C. Myers, who was soon to wed General Twigg’s daughter. Myers was the chief quartermaster of Florida at the time, and although there is no record of him ever visiting his namesake, all buildings had to be constructed in accordance with plans he alone approved. With nearly unlimited funds, the fort became one of the finest, if not the most expensive, in the country. “So much government money was spent on the fort during the 1850s that the War Department ordered an investigation.”

Abandoned in June of 1858 after Billy Bowlegs and his tribe boarded the Grey Cloud for New Orleans, the fort sat vacant for five years. But in January of 1964, it was newly garrisoned – not by Confederate forces, but by the Union Army whose mission it was “to send horse soldiers into the area north of the Caloosahatchee River to confiscate the stock from cattle ranchers, thus preventing the shipment of beef herds to the Confederate Army in Georgia.” The fort also became a refuge for a handful of escaped slaves and Union sympathizers.

Abandoned in June of 1858 after Billy Bowlegs and his tribe boarded the Grey Cloud for New Orleans, the fort sat vacant for five years. But in January of 1964, it was newly garrisoned – not by Confederate forces, but by the Union Army whose mission it was “to send horse soldiers into the area north of the Caloosahatchee River to confiscate the stock from cattle ranchers, thus preventing the shipment of beef herds to the Confederate Army in Georgia.” The fort also became a refuge for a handful of escaped slaves and Union sympathizers.

“Using the fort as the central image for this mural,” Revelle explains, “allowed a pretext for picturing many events important to representing an alternative and perhaps more objective history of Fort Myers.”

* * * * *

The 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops

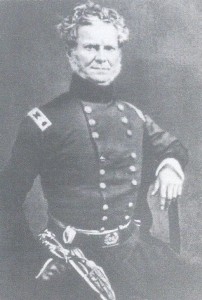

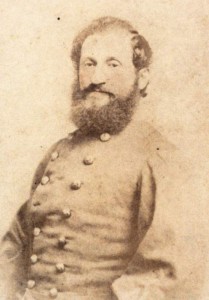

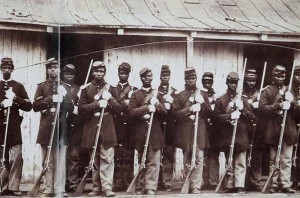

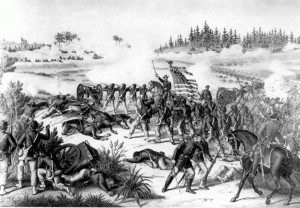

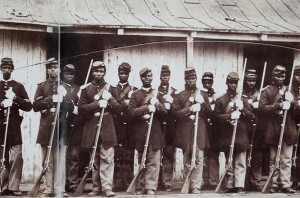

Depicted to the right of Chief Billy Bowlegs and beneath the stockade of the old fort are 15 members of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. The 2nd and 99th regiments served under the command of Union Army General

Depicted to the right of Chief Billy Bowlegs and beneath the stockade of the old fort are 15 members of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. The 2nd and 99th regiments served under the command of Union Army General  Daniel P. Woodbury, Department of the Gulf’s District of Key West. (It is not known whether these soldiers were detached to Company D or Company I.)

Daniel P. Woodbury, Department of the Gulf’s District of Key West. (It is not known whether these soldiers were detached to Company D or Company I.)

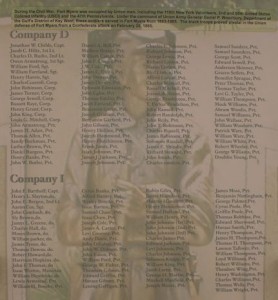

Many accounts place the number of African American troops assigned to Fort Myers in 1865 at 250, but the roster provided by the Williams  Academy Black History Museum in Dunbar contains but 168 names, 91 belonging to Company D and 77 to Company I. Whatever the actual number, they were called up from Fort Zachary Taylor in the Florida Keys to reinforce members of the 2nd Florida Calvary and 110th New York Infantry when resistance from local cattle ranchers threatened to become violent as soldiers in the fort began confiscating their herds.

Academy Black History Museum in Dunbar contains but 168 names, 91 belonging to Company D and 77 to Company I. Whatever the actual number, they were called up from Fort Zachary Taylor in the Florida Keys to reinforce members of the 2nd Florida Calvary and 110th New York Infantry when resistance from local cattle ranchers threatened to become violent as soldiers in the fort began confiscating their herds.

The soldiers of Companies D and I served with enthusiasm and valor during the waning days of the Civil War, and defended Fort Myers from Confederate  attack in a battle that took place on February 20, 1865. Their story is recounted in connection with another tribute to their bravery and sacrifice, D.J. Wilkins’ Clayton, a statue that stands in the eastern section of the River District’s Centennial Park.

attack in a battle that took place on February 20, 1865. Their story is recounted in connection with another tribute to their bravery and sacrifice, D.J. Wilkins’ Clayton, a statue that stands in the eastern section of the River District’s Centennial Park.

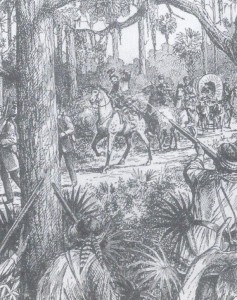

At right is a photograph of a mock-up of the battle on display at the IMAG History & Science Center. As the diorama depicts, by 1865, the wooden stockade (fence) that was built in the 1850s no longer existed and had been replaced by earthen breastworks 15 feet wide by 7 feet in height. The fort’s  cannons had to be wheeled outside the earth works in order to be fired upon the attacking Confederate forces. The actual distance between the attacking forces was actually greater than could be depicted in the diorama.

cannons had to be wheeled outside the earth works in order to be fired upon the attacking Confederate forces. The actual distance between the attacking forces was actually greater than could be depicted in the diorama.

“Fort Myers was a Union stronghold in a state  otherwise predominately held by the Confederates,” writes Barbara Jo Revelle of this section of her mural. “African American slaves actually built the Fort Myers fort, and have had, for many reasons, a very important place in the history of the community … The African American character and culture and the unique social and economic contribution of these people to the

otherwise predominately held by the Confederates,” writes Barbara Jo Revelle of this section of her mural. “African American slaves actually built the Fort Myers fort, and have had, for many reasons, a very important place in the history of the community … The African American character and culture and the unique social and economic contribution of these people to the  history of Fort Myers is complex and multi-faceted. However, I believe the image of African American Union soldiers who occupied the fort during the Civil War will be a source of pride for this community, and for the city as a whole.”

history of Fort Myers is complex and multi-faceted. However, I believe the image of African American Union soldiers who occupied the fort during the Civil War will be a source of pride for this community, and for the city as a whole.”

To understand this sentiment, it helps to know that in January of 1997, an article in Population Today magazine named the greater Fort Myers area “one of the most segregated in the South.” The magazine quoted a University of Michigan study of living patterns indicated by the 1990 U.S. Census Bureau, and within days concerned members of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Fort Myers established an ad hoc committee under the name of Lee County Pulling Together (LCPT) to explore what the community could do to reduce racial division. The mural was created and dedicated in the aftermath of this controversial report, as was D.J. Wilkins’ statue of Clayton, which is dedicated to the more than 180,000 African Americans who fought on the side of the Union in the Civil War.

* * * * *

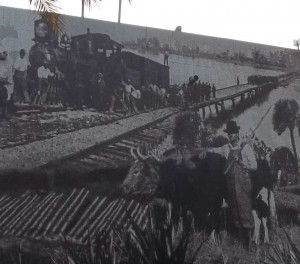

Many people are surprised to discover that Fort Myers was also a cattle town during the latter half of the 19th Century. “After the Civil War, a primary reason Fort Myers grew and prospered was that it was the one and only accessible trading center for a rapidly growing cattle industry,” writes Revelle in her Guidebook for the mural. “Fort Myers was for many years a cow town, and since the actual fort figured early on into the cattle raids that played a major role in the Civil War, it seemed important to

Many people are surprised to discover that Fort Myers was also a cattle town during the latter half of the 19th Century. “After the Civil War, a primary reason Fort Myers grew and prospered was that it was the one and only accessible trading center for a rapidly growing cattle industry,” writes Revelle in her Guidebook for the mural. “Fort Myers was for many years a cow town, and since the actual fort figured early on into the cattle raids that played a major role in the Civil War, it seemed important to  reference cattle in the mural.

reference cattle in the mural.

As a technical point, however, the trading center for the cattle operation was not located in Fort Myers but on Punta Rassa near the location where Fort Dulany had been destroyed by a hurricane in 1841. “To support the blockade of Florida during the Civil War,” notes Revelle, “the U.S. Army had built barracks and warehouses for troops … When  the troops at Fort Myers began bringing in cattle from the Rebel ranches, the herds were shipped out of Punta Rassa to Key West [and] cattle loading chutes had to be built … to get the animals aboard the boats.” The cattle chutes were left intact, and after the Spanish army was sent to quell a rebellion in Cuba, Punta Rassa became a thriving

the troops at Fort Myers began bringing in cattle from the Rebel ranches, the herds were shipped out of Punta Rassa to Key West [and] cattle loading chutes had to be built … to get the animals aboard the boats.” The cattle chutes were left intact, and after the Spanish army was sent to quell a rebellion in Cuba, Punta Rassa became a thriving  port for cattle shipments to Havana.

port for cattle shipments to Havana.

Fort Myers benefited as well. Rather than live on the prairies where the cattle grazed, the cattlemen moved their families into the tiny hamlet of Fort Myers. “Relatives joined them, and by 1873 about ten families were living in the little settlement.”

* * * * *

While Fort Myers grew as a direct and proximate result of the thriving cattle trade, its development was limited by its lack of rail service. “The nearest railroad was at Cedar Key, 200 miles up the coast … Without railroad or commercial activities, making a living depended on the occasional sailboat that came to take a few farm products to Key West. The citizens of Fort Myers lived mainly on fish, game, and their homegrown vegetables and beef.”

The city grew slowly. By the early 1880s, the town had 300 residents, with several hundred more living in the surrounding countryside. By 1890, the town had 1,500 people. And the population doubled in the ensuing 10 years. “[But] by most standards, the little town was still a backwater community,” Revelle notes. In the end, it wasn’t cattle, sugar or Alligator hides that secured rail service to the hamlet of Fort Myers. It was citrus. After the “Big Freeze of 1894 and another longer freeze in February of 1895 ravaged the state’s citrus groves everywhere but in Lee County. “After the freeze, the growers from the north came to buy whatever groves were available and land to plant new groves. The citrus industry along the Caloosahatchee River became viable and extremely profitable and that attracted” first steamboats and, in 1904, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad.

“The last tracks were laid February 20, 1904. As the locomotive chugged forward pushing the flat car carrying the rails to be laid, the ladies of the town who had bedecked the steam engine, including the engineer, with garlands of flowers, took control of the train and kept the bell ringing and the whistle blowing. A brass cannon fired a salute, the crowd cheered and Fort Myers was at last launched into the twentieth century.”

* * * * *

Why Barbara Jo Revelle

The General Services Administration in Washington commissioned photography artist Barbara Jo Revelle to make the mural in 1997 following a national call for artists’ submissions. [Please see below for more information on the federal government’s Art in Architecture Program.]

The General Services Administration in Washington commissioned photography artist Barbara Jo Revelle to make the mural in 1997 following a national call for artists’ submissions. [Please see below for more information on the federal government’s Art in Architecture Program.]

Revelle gained national notoriety in 1991 when she completed a photo-based, computer-generated tile  mural on the Denver Convention Center that is two city blocks long. Titled A People’s History of Colorado, it is still one of the largest outdoor public art murals in the world. Between 1991 and 1997, Ms. Revelle went on to render murals on the new public library in Lafayette, Colorado, the clock tower that is part of the Safety and Justice Building in Longmont, Colorado, and a documentary photo-mural for the Hancock Center, IBM Building and Uptown Hull House Gallery in Chicago that was sponsored by the Chicago Council of Fine Arts.

mural on the Denver Convention Center that is two city blocks long. Titled A People’s History of Colorado, it is still one of the largest outdoor public art murals in the world. Between 1991 and 1997, Ms. Revelle went on to render murals on the new public library in Lafayette, Colorado, the clock tower that is part of the Safety and Justice Building in Longmont, Colorado, and a documentary photo-mural for the Hancock Center, IBM Building and Uptown Hull House Gallery in Chicago that was sponsored by the Chicago Council of Fine Arts.

Prior to her retirement from teaching in 2011, Revelle served as a Professor and Director of the Photography Area of the University of Florida in Gainesville, where she had also served as Director of the School of Art and Art History between 1996 and 2000. Prior to that, she was director of the Photography and Electronic Media Program at the University of Colorado in Boulder for 13 years.

Prior to her retirement from teaching in 2011, Revelle served as a Professor and Director of the Photography Area of the University of Florida in Gainesville, where she had also served as Director of the School of Art and Art History between 1996 and 2000. Prior to that, she was director of the Photography and Electronic Media Program at the University of Colorado in Boulder for 13 years.

Over a span of more than 30 years, Revelle has taught art in many locations throughout the country, including San Francisco Art Institute, UCLA, the University of Colorado in Boulder, The School of the Art Institute and The Institute of Design in Chicago, Arizona State University, N.Y. State University College in Buffalo and the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence.

Revelle has exhibited nationally and internationally in more than 35 individual and 130 group shows in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Japan, Mexico, Germany, France, Sweden, Australia and England. Her work is owned by 41 public collections here and abroad including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York,

Revelle has exhibited nationally and internationally in more than 35 individual and 130 group shows in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Japan, Mexico, Germany, France, Sweden, Australia and England. Her work is owned by 41 public collections here and abroad including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York,  the Bibliotheque National in Paris, the Eikoh Hosoe Collection in Tokyo, the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Her work has received critical acclaim in Art Forum, Z Magazine, Ten/8, Art Week, Afterimage, the New Art Examiner and a host of other journals and art publications.

the Bibliotheque National in Paris, the Eikoh Hosoe Collection in Tokyo, the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Her work has received critical acclaim in Art Forum, Z Magazine, Ten/8, Art Week, Afterimage, the New Art Examiner and a host of other journals and art publications.

How it was made

To create Fort Myers: An Alternative History, Revelle spent two years pouring over historical documents and treatises, including James W. Covington’s The Seminoles of Florida; Karl H. Grismer’s The Story of Fort Myers; and The New History of Fort Myers, edited by Michael Gannon. She created vanilla folders for Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs, the Seminole Indians, the fort built along the banks of the  Caloosahatchee River during the Seminole Wars, and the soldiers of Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops which occupied and defended the fort during the waning days of the Civil War in what turned out to be the southernmost engagement of that conflict. The USCT was assigned to the fort in order to prevent the shipment of cattle to Confederate troops

Caloosahatchee River during the Seminole Wars, and the soldiers of Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops which occupied and defended the fort during the waning days of the Civil War in what turned out to be the southernmost engagement of that conflict. The USCT was assigned to the fort in order to prevent the shipment of cattle to Confederate troops  fighting in Georgia by ranchers who had established a bustling cattle ranching industry prior to the South’s cessation from the United States.

fighting in Georgia by ranchers who had established a bustling cattle ranching industry prior to the South’s cessation from the United States.

Revelle digitized the photographs and then transferred the digital prints to thousands of ceramic tiles using print technologies considered innovative in the 1990s. The resulting sepia-toned graded mosaic tiles then had to be affixed to the pre-cast concrete walls of the courthouse by masons using a master digital montage print-out like the blueprint to an immense jigsaw puzzle.

The installation required the same techniques and preparation that swimming pool contractors use when installing ceramic tile accents to a pool or water feature. Revelle recommended that the smooth precast concrete be sand blasted “immediately prior to the installation to fully clean the surface,” which needed to be devoid of oil and release agents. Working from an intricate network of scaffolds, the masons then applied a 1/8th inch thick coat of skim coat to the concrete substrate before bedding the tiles in thin-set latex-modified Portland cement mortar. These practices were required as a precaution against cracking in the torrid temperatures that the surface of the mural can reach during afternoons in the blazing southwest Florida sun.

The result is a breathtaking mural that pictorially chronicles a 46-year span framed by the departure of Chief Billy Bowlegs and 123 of his people aboard the steamer Grey Cloud bound for New Orleans on May 4, 1858 and the arrival of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad in Fort Myers on February 20, 1904.

A Note about the Federal Art-in-Architecture Program

Incorporating art in U.S. government buildings has been a tradition since 1855, when Congress commissioned Constantino Brumidi to paint frescoes in the committee hearing rooms of the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. Today, the Public Buildings Service of the General Services Administration or GSA continues this tradition of commissioning fine art for federal buildings nationwide through its Art in Architecture Program, which mandates that up to one-half of one percent (0.5%) of the cost of constructing a federal building be allocated for works of art.

As a matter of public policy, the concept of dedicating a percentage of construction costs for the acquisition of public art dates back to the New Deal and the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, which was established in 1934. That program set aside approximately one percent of a federal building’s cost for artistic decoration. The program had nothing to do with New Deal welfare relief or make-work initiatives. It merely codified the nation’s longstanding practice of decorating its public buildings. Unfortunately, the concern for public art waned with America’s entry into World War II, and the program was officially disbanded in 1943.

The percent-for-art program reappeared 20 years later after President Kennedy’s Ad Hoc Committee on Government Office Space recommended that fine art be incorporated, where appropriate, in the design of federal buildings. But just three years after the Government Services Administration re-established it in the spring of 1963, the program was again suspended, this time because of budgetary pressures relating to the war in Southeast Asia and widespread apathy on the part of the general public.

Today’s iteration of the federal percent-for-art program takes its impetus from a presidential directive issued by President Richard Nixon on May 16, 1972 that once again espoused “a program for including artworks in new Federal buildings.” Taking its lead from the Nixon directive, the GSA reinstated the Art-in-Architecture policy that September, declaring “a fresh commitment to commission the finest American artists,” and the country has enjoyed a percent-for-art program ever since.

Today, hundreds of GSA-commissioned works of fine art enrich federal buildings in every part of the country, including downtown Fort Myers, which boasts Fort Myers: An Alternative History by Barbara Jo Revelle.

N.B.: Twenty-one states also embrace public art through percent-for-art statutes. Florida is one of them, with section 255.043 of the Florida Statutes creating Florida’s Art in State Buildings program. Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, Washington and Wyoming have also adopted percent-for-art laws, with Maryland, North Carolina and Vermont requiring annual allocations for public art from either general revenues or their capital improvement funds.

Lee County does not have a formal public art program. The city of Fort Myers does, but its percent-for-art ordinance is voluntary rather than mandatory. As presently structured, Fort Myers Ordinance 118.7.7 encourages “private and public developments … with a building construction value of $250,000 or more … to donate an amount of not less than 0.75 percent of such costs for acquisition and installation of fine art on the development site, but not to exceed the sum of $75,000 ….”

Fast Facts.

- The mural was commissioned in 1997.

- The cost of the commission was $110,000.

- Revelle received an additional $14,000 to prepare a Guidebook pertaining to the mural and its creation.

- The mural was installed in January of 1999.

- Chief Billy Bowlegs also went by the name of Hollatter Micco or Halpuda Mikko, which means Alligator Chief in Seminole. His surname Bowlegs is not a reference to the chief being bowlegged as a result of riding horses bareback. Rather, he had a remote French ancestor in the form of a French trader named Beaulieu, which became contracted somehow or other to Bolek. But when Billy pronounced the name, it sounded like “Bowlegs,” which is what the whites called him.

- Bowlegs had a reputation of being a hot head, but in reality, he and the Indian nations of Florida were lied to so frequently and consistently, he can hardly be blamed for despising the white soldiers and settlers who made his life and those of his fellow tribesmen a living hell. One shameful example involved Major General Alexander Macomb, commander-in-chief of the American Army, who told the Indians that they could have all the lands south of the Peace River and west of Lake Okeechobee when, in reality, the treaty he negotiated was only meant to be temporary, until they could be rounded up and deported to Indian territory in Arkansas.

- Some authors mistakenly claim that Billy Bowlegs gained distinction after his arrival in Oklahoma serving as a captain in the Union Army’s First Indian Regiment, “protecting his new home from Confederate attempts to control it.” However, is was Sonuk Mikko, not Halpuda Mikko, who gained fame as a captain in the Union Army during the Civil War. Both Halpuda Mikko and the later Sonuk Mikko were called Billy Bowlegs.

Other Public Art Installations in City of Fort Myers

Fort Myers: An Alternative History is one of 7 major public art installations in the City of Fort Myers. The others include Fire Dance, a 25-foot Dupont red proto-architectural piece by Ohio metal sculptor David Black; Parallel Park by Marylyn Dintenfass, a 30,000 square foot project that has transformed the 5-story Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage into an outdoor work of experiential art; Caloosahatchee Manuscripts by Jim Sanborn, which lights up the façade of the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center at night; Naiad by Albert Paley, a colorful 30-foot tall polychromed steel sculpture that guards the front entrance of the St. Tropez/Riviera Condominium Complex on East First Street; Uncommon Friends by D.J. Wilkins, which includes a fountain, a 40-foot diameter pool and a 20-foot island on which Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone lounge around a campfire no doubt discussing their next great inventions; and Clayton, D.J. Wilkins’ memorial to the men of Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops.

Related Articles.

Conservation of Barbara Jo Revelle mural underway in downtown Fort Myers River District (03-11-15)

Conservation of Fort Myers: An Alternative History is underway in the downtown Fort Myers River District. The $92,892 project is designed to reattach rows of tiles that have been popping off the mural as the underlying concrete wall slabs expand and contract in the searing Southwest Florida sunshine and torrid heat.

Conservation of Fort Myers: An Alternative History is underway in the downtown Fort Myers River District. The $92,892 project is designed to reattach rows of tiles that have been popping off the mural as the underlying concrete wall slabs expand and contract in the searing Southwest Florida sunshine and torrid heat.

Located on the eastern face of the federal  courthouse, which fronts on the courtyard that it shares with Hotel Indigo and Starbucks, Fort Myers: An Alternative History is a 100 foot long by 20 foot, 8 inch tall sepia tone ceramic tile mural. It was commissioned in 1997 by the Public Buildings Service of the Government Services Administration pursuant to the U.S. government’s Art in Architecture Program, which mandates that

courthouse, which fronts on the courtyard that it shares with Hotel Indigo and Starbucks, Fort Myers: An Alternative History is a 100 foot long by 20 foot, 8 inch tall sepia tone ceramic tile mural. It was commissioned in 1997 by the Public Buildings Service of the Government Services Administration pursuant to the U.S. government’s Art in Architecture Program, which mandates that  one-half of one percent (0.5%) of the cost of constructing a federal building be allocated for works of art. Then Director of the School of Art and Art History Barbara Jo Revelle was chosen for the mural project following a national call to artists.

one-half of one percent (0.5%) of the cost of constructing a federal building be allocated for works of art. Then Director of the School of Art and Art History Barbara Jo Revelle was chosen for the mural project following a national call to artists.

The mural features historical photographs that  span a 54-year period (roughly 1850-1904) of Fort Myers’ pre and early history which Revelle found, digitized and transferred to thousands of 1-in-square ceramic tiles.

span a 54-year period (roughly 1850-1904) of Fort Myers’ pre and early history which Revelle found, digitized and transferred to thousands of 1-in-square ceramic tiles.

“The wall is covered with approximately 248 tiles vertically (1 inch square) and approximately 1,200 tiles in the horizontal direction,” reports McKay Lodge, Inc., which is doing the restoration work. “The total number of tiles is therefore approximately 297,600,” although McKay Lodge notes that determining the precise number of tiles is  complicated by the fact that a number of 1 x 1 inch tiles are actually composed of 4¼ inch squares.

complicated by the fact that a number of 1 x 1 inch tiles are actually composed of 4¼ inch squares.

But problems occurred during the tiles’ original installation. Today, best practices require the use of a crack suppression membrane whenever and wherever ceramic tile or Travertine crosses and expansion joint. The 13 concrete panels that comprise the east wall of the federal building are separated by 12 vertical expansion joints, but when the original team of masons first installed the  mural, they bed the tiles in latex-fortified Portland mortar without crack suppression, and that’s where the tiles have been popping off the wall for several years now.

mural, they bed the tiles in latex-fortified Portland mortar without crack suppression, and that’s where the tiles have been popping off the wall for several years now.

“There are many places where tiles are not bonding, especially over all of the expansion joints,” reports McKay Lodge, which adds that  many tiles have been lost and need to be replaced. “After considerable mock-up experiments, a solution to keeping tiles bonded over expanding and contracting joints has been developed at McKay Lodge, Inc. The treatment will remove all tiles over the expansion joints and reinstall them over the joints in a way that expansion and contraction can occur without causing disbonding or obvious vertical lines.”

many tiles have been lost and need to be replaced. “After considerable mock-up experiments, a solution to keeping tiles bonded over expanding and contracting joints has been developed at McKay Lodge, Inc. The treatment will remove all tiles over the expansion joints and reinstall them over the joints in a way that expansion and contraction can occur without causing disbonding or obvious vertical lines.”

In addition to wall paintings, murals and mosaics, McKay Lodge has been active in the conservation of paintings, works on paper, architectural features, sculpture, public art, monuments, metal artifacts and both modern and historic fountains for more than 25 years. Run by founder Robert Lodge and his son Emmett, the company functions as a general contractor utilizing conservation experts, assistants and others throughout the United States as its “staff” to accomplish its conservation work. Employees of Oberlin Conservation Associates, LLC, located at 9

In addition to wall paintings, murals and mosaics, McKay Lodge has been active in the conservation of paintings, works on paper, architectural features, sculpture, public art, monuments, metal artifacts and both modern and historic fountains for more than 25 years. Run by founder Robert Lodge and his son Emmett, the company functions as a general contractor utilizing conservation experts, assistants and others throughout the United States as its “staff” to accomplish its conservation work. Employees of Oberlin Conservation Associates, LLC, located at 9  West College Street in Oberlin, Ohio, serve as the core of the company’s “staff.”

West College Street in Oberlin, Ohio, serve as the core of the company’s “staff.”

The mural contains photo-based images of Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs and members of his tribe preparing to board the steamer Gray Cloud bound for deportation to Indian territory in Oklahoma; the pine stockade of the fort from which Fort Myers derives its name; a contingent of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops that defended the outpost from  Confederate attack in the waning days of the Civil War; a rancher representing the cattlemen who built Fort Myers into a rowdy, rough and tumble cow town in the last quarter of the 19th Century; and the day (February 20, 1904) that the last spike was driven by Julia Isabel Frierson Hendry into the railroad ties that brought the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad to town, propelling Fort Myers into the modern era.

Confederate attack in the waning days of the Civil War; a rancher representing the cattlemen who built Fort Myers into a rowdy, rough and tumble cow town in the last quarter of the 19th Century; and the day (February 20, 1904) that the last spike was driven by Julia Isabel Frierson Hendry into the railroad ties that brought the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad to town, propelling Fort Myers into the modern era.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.