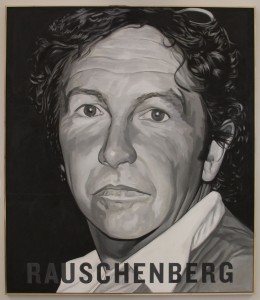

Bob Rauschenberg

On this page you will find articles about artist Bob Rauschenberg.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Dede Sweet reflects back on the night Bob Rauschenberg popped into the grand opening of her North Naples gallery (10-29-14)

“Who owns this gallery?” Robert Rauschenberg demanded loudly as he walked through the red French doors of Sweet Art Gallery in North Naples. He was alone, wearing a festive holiday vest, clearly on his way to a Christmas party somewhere else in Naples later that night. But that’s not what the gallery’s owner, Dede Sweet, was thinking as she ran up to meet him.

“Who owns this gallery?” Robert Rauschenberg demanded loudly as he walked through the red French doors of Sweet Art Gallery in North Naples. He was alone, wearing a festive holiday vest, clearly on his way to a Christmas party somewhere else in Naples later that night. But that’s not what the gallery’s owner, Dede Sweet, was thinking as she ran up to meet him.

“Are you Code Enforcement?” she asked, frantic. Just her luck. She’d jumped the starting gun and opened without having her C.O. (Certificate of Occupancy) in place, and now she was about to suffer the embarrassment and indignation of being closed down on opening night with a gallery full of first time guests and potential lifelong patrons. Someone on Trade Center Way must have turned her in.

In spite of turning almost hypoxic, Sweet was taken aback by how handsome the inspector was. “He looked like Peter O’Toole,” Sweet recalled as she recounted the story on what would have been the artist’s 89th birthday a handful of days ago.

In spite of turning almost hypoxic, Sweet was taken aback by how handsome the inspector was. “He looked like Peter O’Toole,” Sweet recalled as she recounted the story on what would have been the artist’s 89th birthday a handful of days ago.

“No one ever opens a gallery without inviting me,” the man chided. “I’m a collector,” he added with a grin, allowing Sweet to breathe again now that he’d  reassured her that she’d dodged the Code Enforcement bullet.

reassured her that she’d dodged the Code Enforcement bullet.

But now a new form of anxiety welled up in Sweet’s computer-efficient business mind. She had apparently offended an important local private collector by omitting his name from her extensive  guest list. How could that happen? “Do you live in Naples?” she asked, scanning in her mind’s eye the Naples communities she’d scoured for invitees to her grand opening.

guest list. How could that happen? “Do you live in Naples?” she asked, scanning in her mind’s eye the Naples communities she’d scoured for invitees to her grand opening.

“I live on the beach,” Bob said flatly as he allowed the tall, statuesque blond to take him by the bicep and escort him around.

“I’m sorry. That’s my bad,” Sweet apologized. “I’m Dede Sweet and I’ll make it up to you,” she told him. He reached out a hand to her. “I’m Jonathan Green, and you could start by offering me something stronger than a glass of wine.”

Sweet glanced at the Woodbridge on the makeshift bar. “I’m sorry  for the second time,” she said shaking her head woefully. “This is all I have.”

for the second time,” she said shaking her head woefully. “This is all I have.”

Sweet fretted about the encounter the rest of the night. “I really felt that I’d insulted him by not having him on my guest list,” she says, thinking back on that night several years ago. “So the next day I tried to find Jonathan Green in Port Royal, on Gulfshore Drive, in Old Naples. I was going to  send him a flask of the best Vodka I could find with a note saying that from now on he would never be left off my invitation list. But I couldn’t find any address for a Jonathan Green on the beach.”

send him a flask of the best Vodka I could find with a note saying that from now on he would never be left off my invitation list. But I couldn’t find any address for a Jonathan Green on the beach.”

As luck would have it, a girlfriend invited Dede to go with her some time later to a birthday party for a friend by the name of Jonathan Green. “Could it be the same Jonathan Green,” Sweet asked herself on the way to the party. But this Jonathan Green didn’t live on the beach and when her friend introduced her, Sweet was  disappointed to find that it wasn’t the same man. As she told the actual Jonathan Green her story, he tilted his head back and roared. “That was Bob Rauschenberg,” he told a dumbfounded Sweet between peals of laughter. And it had been his Christmas party that Bob had been on his way to the night he’d dropped in on Sweet’s grand opening.

disappointed to find that it wasn’t the same man. As she told the actual Jonathan Green her story, he tilted his head back and roared. “That was Bob Rauschenberg,” he told a dumbfounded Sweet between peals of laughter. And it had been his Christmas party that Bob had been on his way to the night he’d dropped in on Sweet’s grand opening.

Sweet never did get to see Rauschenberg again. “I was at abstract artist Mary Ann Flynn-Flouse’s house when we heard the news that Bob had died. We both cried and shared a moment of grief over having lost one of our great ones,” says Sweet, choking up even now.

Just this past month Sweet got to share her story with Darryl Pottorf’s sister, Jennifer Benton, at the Arts for ACT Fine Art Auction preview that Sweet Art hosted. The Abuse & Counseling Treatment director knew Rauschenberg well. Not only was her brother Bob’s closest friend, studio assistant and artistic collaborator, but Bob supported ACT’s mission by donating prints and original works to the Arts for ACT Fine Art Auction for years preceding his death in 2008. In fact, three Rauschenberg prints will be included in this year’s fine art auction in the Harborside Event Center on November 8.

Just this past month Sweet got to share her story with Darryl Pottorf’s sister, Jennifer Benton, at the Arts for ACT Fine Art Auction preview that Sweet Art hosted. The Abuse & Counseling Treatment director knew Rauschenberg well. Not only was her brother Bob’s closest friend, studio assistant and artistic collaborator, but Bob supported ACT’s mission by donating prints and original works to the Arts for ACT Fine Art Auction for years preceding his death in 2008. In fact, three Rauschenberg prints will be included in this year’s fine art auction in the Harborside Event Center on November 8.

“Sounds just like him,” Benton said when Sweet completed the story.

And what would Sweet have done had the artist given her his real name that night at her grand opening? “If he would have told me he was Bob Rauschenberg, I would have fainted on the spot,” Sweet admits. “But he was such a card. He was cutting up that night and didn’t want me to know who he was. He wanted to remain incognito.”

It was just Bob being Bob, and that night, it was Dede Sweet who got to deal with it.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Recalling how revolutionary and transcendent Bob Rauschenberg was on the 89th anniversary of his birth (10-22-14)

Today is the anniversary of Bob Rauschenberg’s birthday. He would have been 89. With the assistance of the Guggenheim Museum’s Julia Blaut and author and cultural provocateur Dave Hickey, today might be a great time to remind ourselves just how revolutionary and transcendent Captiva’s favorite son really was.

Today is the anniversary of Bob Rauschenberg’s birthday. He would have been 89. With the assistance of the Guggenheim Museum’s Julia Blaut and author and cultural provocateur Dave Hickey, today might be a great time to remind ourselves just how revolutionary and transcendent Captiva’s favorite son really was.

“Rauschenberg’s art was always one of thoughtful inclusion,” Blaut wrote for Guggenheim Bilbao in 1998. “Working with a wide range of subjects, styles, materials and techniques, Rauschenberg was called a forerunner of virtually every postwar movement since Abstract Expressionism. He remained, however, independent of any particular affiliation. At the time he began making art in the late 1940s, his belief  that painting relates to both art and life presented a direct challenge to the prevalent Modernist aesthetic. The celebrated Combines begun in the mid1950s brought real world images and objects into the realm of abstract painting and countered sanctioned divisions between painting and sculpture. These works established the artist’s ongoing dialogue between mediums, between the handmade and the readymade, and between the gestural brushstroke and the mechanically reproduced image.”

that painting relates to both art and life presented a direct challenge to the prevalent Modernist aesthetic. The celebrated Combines begun in the mid1950s brought real world images and objects into the realm of abstract painting and countered sanctioned divisions between painting and sculpture. These works established the artist’s ongoing dialogue between mediums, between the handmade and the readymade, and between the gestural brushstroke and the mechanically reproduced image.”

“Bob’s taste for fecundity and radicalism was what made Bob, Bob,” observed Hickey, who had occasion to reflect  back on his longtime professional and personal relationship with Rauschenberg during an ArtSPEAK @ FSW lecture in the Rush Auditorium on Saturday, October 4. “Bob was unconventional. In fact, when he found himself in a conventional setting, he did the opposite of what was expected.”

back on his longtime professional and personal relationship with Rauschenberg during an ArtSPEAK @ FSW lecture in the Rush Auditorium on Saturday, October 4. “Bob was unconventional. In fact, when he found himself in a conventional setting, he did the opposite of what was expected.”

Rauschenberg did not just combine disparate subjects, styles, materials, techniques and genres. His expansive artistic philosophy included, notes Blaut, a “lifelong commitment to collaboration with performers, printmakers, engineers, writers and artisans from around the world” – both during and in the decades following R.O.C.I. (the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange). [In fact,] fostering  working relationships between artists and engineers was the founding principle of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), an organization established in 1966 by Rauschenberg with, among others, Bell Laboratories research scientist Billy Kluver.” The latter collaboration enabled Rauschenberg to integrate light, sound and motion into large-scale interactive sculptural environments.

working relationships between artists and engineers was the founding principle of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), an organization established in 1966 by Rauschenberg with, among others, Bell Laboratories research scientist Billy Kluver.” The latter collaboration enabled Rauschenberg to integrate light, sound and motion into large-scale interactive sculptural environments.

Taking a chapter out of Napoleon Hill’s Master Mind Principle, collaboration allowed Bob to live in the “big present.” Hickey explains. “For Bob, the present extended back 40 years. It was only there that art history started. By  opening the door to a 40-year present, it gave Bob a big box in which to work, in which to indulge himself.”

opening the door to a 40-year present, it gave Bob a big box in which to work, in which to indulge himself.”

“Rauschenberg’s reputation as the leading artist of his generation was secured,” says Blaut, “by his first solo exhibition, held in 1963, at the Jewish Museum in New York, and the Grand Prize for Painting awarded him the following year at the Venice Biennale.” But Bob didn’t let reputation or success deter him from experimenting in ways that dismayed and confounded his contemporaries, reviewers and critics.

“Bob ran off his own entropy,” Hickey summarizes. “A lot of what made Bob a good artist is that he did bad things. Sparks would fly off  him. He was a good guy who was not a good guy.” His rowdiness, drunkenness and irreverence (like the time he erased a Willem de Kooning drawing as a “happening” or performance art piece) earned him a much-deserved and undoubtedly cherished rep and rap as the bad boy of art.

him. He was a good guy who was not a good guy.” His rowdiness, drunkenness and irreverence (like the time he erased a Willem de Kooning drawing as a “happening” or performance art piece) earned him a much-deserved and undoubtedly cherished rep and rap as the bad boy of art.

“Bob didn’t give a shit,” Hickey says bluntly.

He didn’t have time to worry about what others thought or were doing. “He improvised so quickly,” observed Hickey during his ArtSPEAK remarks, with a shake of the head that underscored his incredulity and admiration.

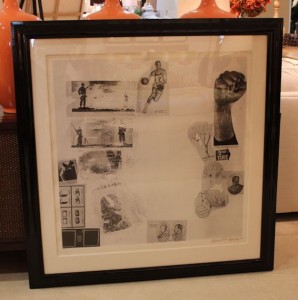

“Expanding upon Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade, Rauschenberg gave new significance to such ordinary objects as a patchwork quilt or an automobile tire by juxtaposing them with unrelated items and placing them in the context of art,” writes Blaut. “By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the found image had become paramount in Rauschenberg’s visual vocabulary. Reproductions from newspapers and magazines were incorporated into his drawings, prints and paintings as he perfected techniques of solvent transfer, lithography and silkscreening. With his move in 1970 from New York to Captiva … he now favored an abstract idiom and the use of natural fibers, such as fabric and paper.” And in 1979, Bob renewed his interest

“Expanding upon Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade, Rauschenberg gave new significance to such ordinary objects as a patchwork quilt or an automobile tire by juxtaposing them with unrelated items and placing them in the context of art,” writes Blaut. “By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the found image had become paramount in Rauschenberg’s visual vocabulary. Reproductions from newspapers and magazines were incorporated into his drawings, prints and paintings as he perfected techniques of solvent transfer, lithography and silkscreening. With his move in 1970 from New York to Captiva … he now favored an abstract idiom and the use of natural fibers, such as fabric and paper.” And in 1979, Bob renewed his interest  in photography. “From this point forward, images incorporated into Rauschenberg’s work in all mediums were drawn exclusively from his own photographs.”

in photography. “From this point forward, images incorporated into Rauschenberg’s work in all mediums were drawn exclusively from his own photographs.”

“But Bob didn’t just create one work of art,” Hickey adds. “’You build one work off of another and another until you have a show,’ Bob said often. ‘You’re always working toward the next show.’”

What made all of his accomplishments possible was his unabashed willingness to take risks and to fail. “He’d make ten works to get one [keeper],” notes Hickey. By contrast,  Jasper Johns (who shared Rauschenberg’s interest in deriving art from the commonplace) would produce two to get one. “Bob was aware of the difference,” chuckles Hickey. “’We’re all on a tightrope,’ he told me once. But Jasper’s tightrope is only three feet off the ground.’”

Jasper Johns (who shared Rauschenberg’s interest in deriving art from the commonplace) would produce two to get one. “Bob was aware of the difference,” chuckles Hickey. “’We’re all on a tightrope,’ he told me once. But Jasper’s tightrope is only three feet off the ground.’”

There is a tendency nowadays to lionize Robert Rauschenberg. Art historians want to canonize him for the role he played in pop art and all aspects of post-modernism. Collectors want to include him on their walls even if they don’t particularly understand or appreciate his art. And according to Hickey, the artist’s own Foundation (which is run by his son, Christopher) wants to turn his paintings into bearer bonds. “But Bob would hate smoothness, political correctness, corporateness and branding. Bob was a free spirit in the woods with some work to do.”

So, given Hickey’s cautionary tale, how should we honor Bob’s memory and evaluate his legacy on this, the 89th anniversary of his birth? Perhaps it is best to reflect not as much on his art and his place in the art world, but on the qualities that distinguished him among his peers and people in general. By that standard, Bob was inclusive, encompassing, expansive and collaborative. He was curious, inquisitive and always willing to experiment and take chances. Not one to let image or brand get in his way, he didn’t mind falling flat on his face and looking like a fool or incurring the wrath, cataclysmic hatred, opprobrium or

So, given Hickey’s cautionary tale, how should we honor Bob’s memory and evaluate his legacy on this, the 89th anniversary of his birth? Perhaps it is best to reflect not as much on his art and his place in the art world, but on the qualities that distinguished him among his peers and people in general. By that standard, Bob was inclusive, encompassing, expansive and collaborative. He was curious, inquisitive and always willing to experiment and take chances. Not one to let image or brand get in his way, he didn’t mind falling flat on his face and looking like a fool or incurring the wrath, cataclysmic hatred, opprobrium or  ridicule of the art world, as he did with the de Kooning happening and R.O.C.I.

ridicule of the art world, as he did with the de Kooning happening and R.O.C.I.

Some might even call Rauschenberg courageous. But they would do so at the risk of Dave Hickey wagging a scolding finger at such an attempt to idolize the man. “That’s antithetical to Bob’s life and lifestyle,” asserts Hickey. “He was willful. Same as Warhol. Bob did not have a biographical narrative. His was an episodic narrative. He saw, interpreted and expressed.”

In other words, he was just Bob being Bob. Deal with it.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Five years later, Bob Rauschenberg still exerts influence on Southwest Florida art community (10-23-13)

Yesterday, Bob Rauschenberg would have turned 88. Although he’s been gone nearly 5 and 1/2 years, Bob’s influence can still be felt on a daily basis throughout the Southwest Florida art community.

Yesterday, Bob Rauschenberg would have turned 88. Although he’s been gone nearly 5 and 1/2 years, Bob’s influence can still be felt on a daily basis throughout the Southwest Florida art community.

Art critics and historians are quick to point out that Rauschenberg’s legacy is as a pioneer whose experimental approach to craft and media paved the way for the likes of Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and all the pop, conceptual, process and performance artists who followed in his wide wake. But Bob did more than merely lay the groundwork for later iconic artists and art movements. His body of work gives continuing permission to subsequent generations of artists to stretch the boundaries of art. To obscure the lines between painting, photography, printmaking, sculpture and performance art even more than he did. To push, prod and re-conceive the media in which they choose to work.

Bob is often remembered for incorporating found objects into his compositions. But Rauschenberg did so much more than further the imperatives begun by Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Schwitters, Joseph Cornell and Louise Nevelson. It wasn’t that he used objets trouve on the surface of his combines and collages. No, he convinced the art world that junk – the flotsam and jetsam produced by everyday life – could not only become artistic media, but could produce beautiful art. “I feel sorry for people who think things like soap dishes or mirrors or Coke bottles are ugly,” Bob once famously stated, “because they’re surrounded by things like that all day long, and it must make them miserable.”

By that standard, then, the artists who work and exhibit in the River District must be happy, vital souls because so many of them constantly push their personal and artistic envelops, blending and blurring media and genre, embracing found objects of every type and description into their imaginative and often perplexing two-dimensional compositions and sculptural pieces. Walk into Arts for ACT or the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center on any given day, and you’ll likely see aspects of Rauschenberg in the work of mixed media artists like Michael St. Amand, Cesar Aguilera, Susan Mills, Bradford Hermann(right), Jonathan Kane and Lisa Freidus. Oh, that’s not to suggest they are intentionally trying to replicate Bob’s work. They don’t have to. His influence persists nonetheless, even if they’re not aware of the debt they owe him for the freedom of artistic expression they enjoy today.

By that standard, then, the artists who work and exhibit in the River District must be happy, vital souls because so many of them constantly push their personal and artistic envelops, blending and blurring media and genre, embracing found objects of every type and description into their imaginative and often perplexing two-dimensional compositions and sculptural pieces. Walk into Arts for ACT or the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center on any given day, and you’ll likely see aspects of Rauschenberg in the work of mixed media artists like Michael St. Amand, Cesar Aguilera, Susan Mills, Bradford Hermann(right), Jonathan Kane and Lisa Freidus. Oh, that’s not to suggest they are intentionally trying to replicate Bob’s work. They don’t have to. His influence persists nonetheless, even if they’re not aware of the debt they owe him for the freedom of artistic expression they enjoy today.

And the fact that so many of these artists find a voice at Arts for ACT would undoubtedly please Bob to no end, as he was an avid supporter during his later years of the gallery and the work ACT does in helping the victims of sexual assault, domestic violence and human trafficking, and their families.

One River District artist who especially exemplifies Bob’s bravado and artistic temperament is Marcus Jansen. Like Rauschenberg, Marcus combines technical skill and expertise with a profound sense of purpose and a truly unique awareness of the world. Like Bob, Marcus addresses major themes of worldwide concern without bombast or pretence. He, too, exploits the messiness of everyday life. He, too, appropriates media images and pop brands like Dorothy from Oz into works that are simultaneously homage and parody. And then there’s that whole car tire and bicycle thing as well, not to mention Jansen’s ever-present quest to incorporate technology in ever more imaginative and inventive ways into not only his startling urban landscapes, but his equally surprising aerials as well.

One River District artist who especially exemplifies Bob’s bravado and artistic temperament is Marcus Jansen. Like Rauschenberg, Marcus combines technical skill and expertise with a profound sense of purpose and a truly unique awareness of the world. Like Bob, Marcus addresses major themes of worldwide concern without bombast or pretence. He, too, exploits the messiness of everyday life. He, too, appropriates media images and pop brands like Dorothy from Oz into works that are simultaneously homage and parody. And then there’s that whole car tire and bicycle thing as well, not to mention Jansen’s ever-present quest to incorporate technology in ever more imaginative and inventive ways into not only his startling urban landscapes, but his equally surprising aerials as well.

Given these similarities, it is interesting that Bob’s former gallery assistant Jonas Stirner is now collaborating with Jansen at UNIT A. And it is through Stirner, Lawrence Voytek, Darryl Pottorf and even Kat Epple that Rauschenberg’s influence continues to be exerted on the Southwest Florida art community. All worked closely with Bob for many years, and although their art is uniquely their own, their process and inventiveness cannot help but reflect their tutelage in Bob’s studio and print shop on Captiva Island. In fact Pottorf is still perfecting the transfer solvent printmaking technique that Bob first developed more than two decades ago.

Given these similarities, it is interesting that Bob’s former gallery assistant Jonas Stirner is now collaborating with Jansen at UNIT A. And it is through Stirner, Lawrence Voytek, Darryl Pottorf and even Kat Epple that Rauschenberg’s influence continues to be exerted on the Southwest Florida art community. All worked closely with Bob for many years, and although their art is uniquely their own, their process and inventiveness cannot help but reflect their tutelage in Bob’s studio and print shop on Captiva Island. In fact Pottorf is still perfecting the transfer solvent printmaking technique that Bob first developed more than two decades ago.

Thanks to the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s $350 million endowment over the next decade and a half, his Captiva compound is now home to 42 artists in residence whose aim is to evoke the cross-fertilization, free-flowing exchange of ideas that Bob experienced first at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College art community and later during his six-year partnership in New York with Jasper Johns, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. (“The four-way exchanges were quite marvelous,” Cage later recalled. “It was the climate of being together that would suggest the work to be done.”) It remains to be seen how this new iteration of Rauschenberg’s art compound will impact the community, but if the lessons Bob taught about the value of collaboration are retaught and relearned, the ripples will soon be felt.

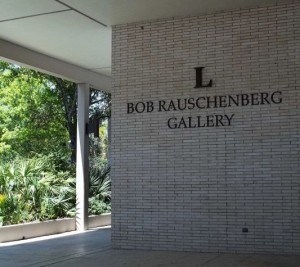

And last, but by no means least is the gallery that bears Bob’s name. With the departure earlier this year of long-time director Ron Bishop, the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Edison State College is now under the stewardship of Jade Dellinger, who many Southwest Florida art lovers and collectors met when he curated a ten-year retrospective of John Cage’s work. Dedicated to furthering the legacy of the gallery’s namesake, Dellinger is busily finalizing plans for a number of exciting exhibitions that will build upon the important – although undervalued – work that Bob did in going overseas to bring art to the world, and the world to Fort Myers.

And last, but by no means least is the gallery that bears Bob’s name. With the departure earlier this year of long-time director Ron Bishop, the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Edison State College is now under the stewardship of Jade Dellinger, who many Southwest Florida art lovers and collectors met when he curated a ten-year retrospective of John Cage’s work. Dedicated to furthering the legacy of the gallery’s namesake, Dellinger is busily finalizing plans for a number of exciting exhibitions that will build upon the important – although undervalued – work that Bob did in going overseas to bring art to the world, and the world to Fort Myers.

Bob Rauschenberg may be gone in body, but his irrepressible, effervescent spirit lives on in many forms and guises here in the Southwest Florida art community that he loved so dearly.

________________________________________________

Robert Rauschenberg’s connection to local arts community

Depressed and in need of a change, he moved from New York City to Captiva Island in 1971. From then until his death on May 12, 2008, his 38-acre compound in Captiva became an epicenter for his artistic output. Not only did he attract a legion of world-class, internationally-renowned artists to Southwest Florida, Rauschenberg supported a host of local galleries and causes, including helping the victims of sexual assault, domestic violence and human trafficking, and their families. Many in this area met the artist and have found memories of him, and a number of his gallery assistants and protégés, including Darryl Pottorf, Lawrence Voytek, Mary Voytek, Jonas Stirner and Kat Epple, exert an ongoing influence over the arts in Southwest Florida. Thanks

Depressed and in need of a change, he moved from New York City to Captiva Island in 1971. From then until his death on May 12, 2008, his 38-acre compound in Captiva became an epicenter for his artistic output. Not only did he attract a legion of world-class, internationally-renowned artists to Southwest Florida, Rauschenberg supported a host of local galleries and causes, including helping the victims of sexual assault, domestic violence and human trafficking, and their families. Many in this area met the artist and have found memories of him, and a number of his gallery assistants and protégés, including Darryl Pottorf, Lawrence Voytek, Mary Voytek, Jonas Stirner and Kat Epple, exert an ongoing influence over the arts in Southwest Florida. Thanks  to the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s $350 million endowment over the next decade and a half, his Captiva compound is now home to 42 artists in residence whose aim is to evoke the cross-fertilization, free-flowing exchange of ideas that Bob experienced first at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College art community and later during his six-year partnership in New York with Jasper Johns, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. And last but by no means least, Rauschenberg’s namesake gallery at Florida SouthWestern State College seeks today to explain, honor and further his artistic legacy. Founded as Edison State College Gallery of Fine Art in 1979, the gallery was renamed on June 4, 2004 as the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery to honor and commemorate its

to the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s $350 million endowment over the next decade and a half, his Captiva compound is now home to 42 artists in residence whose aim is to evoke the cross-fertilization, free-flowing exchange of ideas that Bob experienced first at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College art community and later during his six-year partnership in New York with Jasper Johns, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. And last but by no means least, Rauschenberg’s namesake gallery at Florida SouthWestern State College seeks today to explain, honor and further his artistic legacy. Founded as Edison State College Gallery of Fine Art in 1979, the gallery was renamed on June 4, 2004 as the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery to honor and commemorate its  long-time association and friendship with the artist. Over more than three decades until his death, the Gallery worked closely with Rauschenberg to present world premiere exhibitions including multiple installations of the ¼ Mile or Two Furlong Piece. The artist insisted on naming the space the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery (versus the “Robert Rauschenberg Gallery”) as it was consistent with the intimate, informal relationship he maintained with both the local Southwest Florida community and the community college.

long-time association and friendship with the artist. Over more than three decades until his death, the Gallery worked closely with Rauschenberg to present world premiere exhibitions including multiple installations of the ¼ Mile or Two Furlong Piece. The artist insisted on naming the space the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery (versus the “Robert Rauschenberg Gallery”) as it was consistent with the intimate, informal relationship he maintained with both the local Southwest Florida community and the community college.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.