Karen Glaser Photographs

Florida Gulf Coast University’s public art collection consists of both monumental outdoor sculptures and indoor paintings, photographs and mobiles. Among FGCU’s indoor public art collection are four photographs by renowned photographer Karen Glaser:

Florida Gulf Coast University’s public art collection consists of both monumental outdoor sculptures and indoor paintings, photographs and mobiles. Among FGCU’s indoor public art collection are four photographs by renowned photographer Karen Glaser:

- Dust Storm, a 2006 pigment print photo hanging in the 2nd floor corridor of Academic Building 5 (above right);

- Fire in the Pines #1, a 2010 pigment print photo hanging in Conference Room 210 in Academic Building 5;

- Ichetucknee Fog, a 2010 pigment print photo hanging in the 3rd floor corridor of Academic Building 5; and

- Ichetucknee Cypress, a 2010 pigment print photo hanging in Conference Room 309 of Academic Building 5.

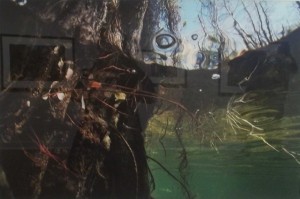

Dust Storm, Ichetucknee Fog (left) and Ichetucknee Cypress come form a series of pictures that Glaser shot predominantly in the pristine freshwater rivers and springs of north and central Florida, places like the Orange Grove Sink in the Peacock Springs Cave System in Suwannee County, Silver Glen in the Ocala National Forest in Marion County, Manatee Springs State Park and

Dust Storm, Ichetucknee Fog (left) and Ichetucknee Cypress come form a series of pictures that Glaser shot predominantly in the pristine freshwater rivers and springs of north and central Florida, places like the Orange Grove Sink in the Peacock Springs Cave System in Suwannee County, Silver Glen in the Ocala National Forest in Marion County, Manatee Springs State Park and  the crystalline Ichetucknee River that flows for six glorious miles through shaded hammocks and wetlands before it joins with the Sante Fe River. But Glaser didn’t trek to the Ichetucknee to tube the river with hordes of students from nearby University of Florida. “My husband and I snorkled the Ichetucknee in winter, when the air was 40 degrees and the water 68,” Glaser recalls. “But we didn’t go then merely to avoid the tubers. That’s when the garfish spawn.” (Above, right.)

the crystalline Ichetucknee River that flows for six glorious miles through shaded hammocks and wetlands before it joins with the Sante Fe River. But Glaser didn’t trek to the Ichetucknee to tube the river with hordes of students from nearby University of Florida. “My husband and I snorkled the Ichetucknee in winter, when the air was 40 degrees and the water 68,” Glaser recalls. “But we didn’t go then merely to avoid the tubers. That’s when the garfish spawn.” (Above, right.)

Before entering a spring, river or swamp to snap pictures, Glaser always does her homework to find out what’s in the body of water she is interested in shooting. Hearkening back to lessons learned in SCUBA, the photographer is also an unwavering adherent of the buddy system. “I always take a partner,” Glaser insists. “You don’t have a long time to take a picture because things change very quickly.” As a result, she has a tendency to become rather single-minded when she is in the middle of an underwater or swamp shoot. “I tend to follow points of interest without paying attention, and that’s where having a partner proves invaluable.”

Before entering a spring, river or swamp to snap pictures, Glaser always does her homework to find out what’s in the body of water she is interested in shooting. Hearkening back to lessons learned in SCUBA, the photographer is also an unwavering adherent of the buddy system. “I always take a partner,” Glaser insists. “You don’t have a long time to take a picture because things change very quickly.” As a result, she has a tendency to become rather single-minded when she is in the middle of an underwater or swamp shoot. “I tend to follow points of interest without paying attention, and that’s where having a partner proves invaluable.”

Her work in north and central Florida’s rivers and springs inculcated a desire in Glaser to shoot Florida’s swamps, so she applied to become an artist in residence at the Big Cypress National Preserve. This move gave her unequaled access to places other people don’t get to explore. Here, too, homework and the buddy system proved invaluable. Asked to relate the worst thing that ever happened to her while shooting in a swamp, Glaser credited her reliance on rangers and other park employees with excusing her from any incidents more harmful than “being covered with welts from mosquito bites.” She also credits park rangers and a helicopter pilot with providing her access to the fire she shuttered for Fire in the Pines #1(right), an image that might have otherwise eluded her.

Her work in north and central Florida’s rivers and springs inculcated a desire in Glaser to shoot Florida’s swamps, so she applied to become an artist in residence at the Big Cypress National Preserve. This move gave her unequaled access to places other people don’t get to explore. Here, too, homework and the buddy system proved invaluable. Asked to relate the worst thing that ever happened to her while shooting in a swamp, Glaser credited her reliance on rangers and other park employees with excusing her from any incidents more harmful than “being covered with welts from mosquito bites.” She also credits park rangers and a helicopter pilot with providing her access to the fire she shuttered for Fire in the Pines #1(right), an image that might have otherwise eluded her.

About Karen Glaser

For more than two decades, Karen Glaser has been photographing underwater ecosystems, including deep water oceans, coastal reefs, freshwater springs, outdoor swimming pools, and wild swamplands. Taking her camera both above and below the surface of America’s coastal waters and Florida’s wetlands, she has captured diverse forms of life that have existed since prehistoric times. Glaser’s photographs of these remote spaces have a timeless quality in the tradition of Audubon’s ornithological watercolors or Da Vinci’s water drawings. Taken with a 35mm camera and only using available light, the images appear distinctively grainy, further abstracting these rarely seen worlds. They elevate the complexity and fragility of aquatic systems that lie beyond the day-to-day perspective of most people.

For more than two decades, Karen Glaser has been photographing underwater ecosystems, including deep water oceans, coastal reefs, freshwater springs, outdoor swimming pools, and wild swamplands. Taking her camera both above and below the surface of America’s coastal waters and Florida’s wetlands, she has captured diverse forms of life that have existed since prehistoric times. Glaser’s photographs of these remote spaces have a timeless quality in the tradition of Audubon’s ornithological watercolors or Da Vinci’s water drawings. Taken with a 35mm camera and only using available light, the images appear distinctively grainy, further abstracting these rarely seen worlds. They elevate the complexity and fragility of aquatic systems that lie beyond the day-to-day perspective of most people.

Glaser’s photography has found a very wide audience through commissions and permanent public art installations. For example, her photographs are held in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Fine Arts in Houston; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City: Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; Portland Art Museum in Oregon; National Park Service; Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago; Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego; Parque de los Deseos in Medellin, Columbia; the LaSalle Bank and Chase Bank collections in Chicago; the New York Public Library; the University of Louisville; the Museum of Science in Miami; Illinois Collection, State of Illinois Center; the Port of Miami; and the David C. and the Sarajean Ruttenberg Collection, Chicago, IL.

Glaser’s photography has found a very wide audience through commissions and permanent public art installations. For example, her photographs are held in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Fine Arts in Houston; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City: Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; Portland Art Museum in Oregon; National Park Service; Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago; Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego; Parque de los Deseos in Medellin, Columbia; the LaSalle Bank and Chase Bank collections in Chicago; the New York Public Library; the University of Louisville; the Museum of Science in Miami; Illinois Collection, State of Illinois Center; the Port of Miami; and the David C. and the Sarajean Ruttenberg Collection, Chicago, IL.

Her work has been featured in many solo exhibitions and been represented in numerous group exhibitions across the United States. In 2011 alone, her photography was the subject of three prestigious solo shows, Dark Sharks/Light Rays at PHOTO in Oakland, California (9/22-10/29/11), The Hillsborough River from the Green Swamp to the Bay at the Tampa Museum of Art (7/2-10/16/11), and The Mark of Water: Florida’s Springs and Swamps, a touring exhibition organized and circulated by the Southeast Museum of Photography, Daytona State College, Daytona Beach, Florida. The Mark of Water exhibited locally at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Edison State College from October 7 through December 3, 2011 and resulted in the highest attendance recorded by the gallery in two years.

Her work has been featured in many solo exhibitions and been represented in numerous group exhibitions across the United States. In 2011 alone, her photography was the subject of three prestigious solo shows, Dark Sharks/Light Rays at PHOTO in Oakland, California (9/22-10/29/11), The Hillsborough River from the Green Swamp to the Bay at the Tampa Museum of Art (7/2-10/16/11), and The Mark of Water: Florida’s Springs and Swamps, a touring exhibition organized and circulated by the Southeast Museum of Photography, Daytona State College, Daytona Beach, Florida. The Mark of Water exhibited locally at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Edison State College from October 7 through December 3, 2011 and resulted in the highest attendance recorded by the gallery in two years.

Glaser’s underwater photographs of manatees are documented in the book, Mysterious Manatees, published by the University Press of Florida and the Center for American Places. A travelling exhibition of her manatee work was organized by the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. It then toured to more than twenty venues in the United States, including the Georgia Museum of Natural History; Ocean Life Center in Atlantic City; Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History in California; the Museum of History and Natural Sciences in Florida; the Naval Undersea Museum inKeyport, Washington; the Natural History Museum of the University of Kansas; and the Natural Science Center of Greensboro, North Carolina.

Glaser’s underwater photographs of manatees are documented in the book, Mysterious Manatees, published by the University Press of Florida and the Center for American Places. A travelling exhibition of her manatee work was organized by the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. It then toured to more than twenty venues in the United States, including the Georgia Museum of Natural History; Ocean Life Center in Atlantic City; Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History in California; the Museum of History and Natural Sciences in Florida; the Naval Undersea Museum inKeyport, Washington; the Natural History Museum of the University of Kansas; and the Natural Science Center of Greensboro, North Carolina.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Glaser holds a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute and an MFA from Indiana University, Bloomington. She is an adjunct instructor of photography in Chicago and has been a guest lecturer at Wild Photos, Royal Geographical Society, London; the USF Humanities Institute (which hosted events celebrating the Hillsborough River through art, literature, history, archeology and ecology in the Fall of 2012); the May, 2013 Blue Mind 3 summit (an annual conference that brings together neuroscientists, oceanographers, explorers, educators and artists to consider “the human brain on water”); the Everglades National Park; Big Cypress National Preserve; Fanning Springs State Park; University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Museum of Science, Miami; Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History, California; University of Illinois at Chicago; Northlight Gallery, Arizona State University; and at Centro Colombo Americano, Escuela Popular de Artes, Universidad de Medellín as part of FotoFiesta.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Glaser holds a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute and an MFA from Indiana University, Bloomington. She is an adjunct instructor of photography in Chicago and has been a guest lecturer at Wild Photos, Royal Geographical Society, London; the USF Humanities Institute (which hosted events celebrating the Hillsborough River through art, literature, history, archeology and ecology in the Fall of 2012); the May, 2013 Blue Mind 3 summit (an annual conference that brings together neuroscientists, oceanographers, explorers, educators and artists to consider “the human brain on water”); the Everglades National Park; Big Cypress National Preserve; Fanning Springs State Park; University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Museum of Science, Miami; Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History, California; University of Illinois at Chicago; Northlight Gallery, Arizona State University; and at Centro Colombo Americano, Escuela Popular de Artes, Universidad de Medellín as part of FotoFiesta.

Glaser has received grants from the Illinois Arts Council and Arts Midwest/National Endowment for the Arts, Visual Arts Regional Fellowship. She has been a Fellow at the Hermitage Artist’s Retreat in Florida and Artist in Residence at both Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve. In 2010, Karen was appointed as the Photographer Laureate for the City of Tampa, Florida, and in February of 2012, the Carnegie Museum of Art and Carnegie Mellon University’s CREATE Lab invited her to join a select group of contemporary artists to participate in a collaborative project involving an innovation called GigaPan. It is new technology developed by CREATE Lab, NASA and Google to explore imaging boundaries and create “something we have never seen before or could have even imagined.”

Glaser has received grants from the Illinois Arts Council and Arts Midwest/National Endowment for the Arts, Visual Arts Regional Fellowship. She has been a Fellow at the Hermitage Artist’s Retreat in Florida and Artist in Residence at both Everglades National Park and Big Cypress National Preserve. In 2010, Karen was appointed as the Photographer Laureate for the City of Tampa, Florida, and in February of 2012, the Carnegie Museum of Art and Carnegie Mellon University’s CREATE Lab invited her to join a select group of contemporary artists to participate in a collaborative project involving an innovation called GigaPan. It is new technology developed by CREATE Lab, NASA and Google to explore imaging boundaries and create “something we have never seen before or could have even imagined.”

Her images have been featured and reviewed in Harper’s, Orion Magazine, Photo District News, Lens Culture, Origo (Hungary), Popular Photography, Swimmers: Seventy International Photographers (Aperture), New Chicago Photographers (Museum of Contemporary Photography) and Alternative Photographic Processes.

Her images have been featured and reviewed in Harper’s, Orion Magazine, Photo District News, Lens Culture, Origo (Hungary), Popular Photography, Swimmers: Seventy International Photographers (Aperture), New Chicago Photographers (Museum of Contemporary Photography) and Alternative Photographic Processes.

A Word About her Photographic Process

What makes Glaser’s photography so appealing is her willingness to go remote places that are exceedingly difficult to reach in order to bring back unique views of rare landscapes, most shot underwater. Glaser’s eye is strongly attracted to ambiguous spaces. “When you are underwater, the space is ambiguous,” Glaser notes. As a result of this emphasis, the viewer is often unsure whether a given image portrays underwater or land-born images, a photograph or a watercolor painting. “This ambiguity is their strength,” says Glaser, “and very much part of the world from which they came.”

What makes Glaser’s photography so appealing is her willingness to go remote places that are exceedingly difficult to reach in order to bring back unique views of rare landscapes, most shot underwater. Glaser’s eye is strongly attracted to ambiguous spaces. “When you are underwater, the space is ambiguous,” Glaser notes. As a result of this emphasis, the viewer is often unsure whether a given image portrays underwater or land-born images, a photograph or a watercolor painting. “This ambiguity is their strength,” says Glaser, “and very much part of the world from which they came.”

Glaser’s photographs are influenced by her art background rather than a biological or scientific point of view. “Several critics have called my pictures ‘messy.’ In a good way. They’re honest. I don’t clean them up.” Many are clouded by the mud, muck, pollen and tannins that are common to Florida’s wetlands. While this detritus and particulate matter may mar the water’s clarity, “it is in fact its lifeblood,” or as Glaser more poetically describes it, “the living and breathing matter that seasons the soup and reflects, refracts, and bends the light to create its complexity.”

Glaser’s photographs are influenced by her art background rather than a biological or scientific point of view. “Several critics have called my pictures ‘messy.’ In a good way. They’re honest. I don’t clean them up.” Many are clouded by the mud, muck, pollen and tannins that are common to Florida’s wetlands. While this detritus and particulate matter may mar the water’s clarity, “it is in fact its lifeblood,” or as Glaser more poetically describes it, “the living and breathing matter that seasons the soup and reflects, refracts, and bends the light to create its complexity.”

As a result of her steadfast refusal to clean up her images, they are as layered, complex and powerful as the environments she captures on film. The effect is amplified by her unwillingness to use flash photography. “I only use natural light.” She also still uses analog film. “I will continue shooting analog until they don’t make film any more,” Glaser avers. That’s not because film is any better than digital technology. “I just like the results I get with film.” She does work with a digital guru, who drum scans her negatives and prints her images digitally, and is now exploring digital photography in earnest in connection with the CREATE Lab’s GigaPan project. “Analog is better for some things and digital is better for others. One is a screwdriver and one is a hammer…they are just different tools.”

As a result of her steadfast refusal to clean up her images, they are as layered, complex and powerful as the environments she captures on film. The effect is amplified by her unwillingness to use flash photography. “I only use natural light.” She also still uses analog film. “I will continue shooting analog until they don’t make film any more,” Glaser avers. That’s not because film is any better than digital technology. “I just like the results I get with film.” She does work with a digital guru, who drum scans her negatives and prints her images digitally, and is now exploring digital photography in earnest in connection with the CREATE Lab’s GigaPan project. “Analog is better for some things and digital is better for others. One is a screwdriver and one is a hammer…they are just different tools.”

In 2010, she took her camera into the waters of Florida’s springs, swamps and waterways to provides a unique interpretation of these distinctive environments. She characterizes the Everglades as “primal,” “primitive” and challenging due to its sheer scale.

In 2010, she took her camera into the waters of Florida’s springs, swamps and waterways to provides a unique interpretation of these distinctive environments. She characterizes the Everglades as “primal,” “primitive” and challenging due to its sheer scale.  “The wetland environments of Big Cypress National Preserve and Everglades National Park contain many unique ecosystems,” says Glaser, “including freshwater and saltwater marshes, dry and wet prairies, hardwood hammocks, mangrove forests, vast acres of primeval swamp, and of course the river of grass. The tie that binds these extraordinary regions and these photographs together is water. Much of this underwater world is primordial or aboriginal; and only partially touched by the hand of culture and society.”

“The wetland environments of Big Cypress National Preserve and Everglades National Park contain many unique ecosystems,” says Glaser, “including freshwater and saltwater marshes, dry and wet prairies, hardwood hammocks, mangrove forests, vast acres of primeval swamp, and of course the river of grass. The tie that binds these extraordinary regions and these photographs together is water. Much of this underwater world is primordial or aboriginal; and only partially touched by the hand of culture and society.”

However, Glaser avoids politicizing her pictures. She leaves it to others to use her pictures “to show people what’s worth saving.” Instead, she focuses on merely making her images as seductive. “Seductive images cause people to think versus telling them what to think.” For Glaser, though, part of the seduction is knowing that many of her Big Cypress and Everglades National Park shots came from wild, untouched swamps “a mere forty-five minutes from the sprawl of Miami to the east and Naples to the west.”

Because of the environmental content, depth and resolution of her images, it is tempting to draw comparisons between Glaser’s work and that of Ansel Adams. “I’m closer in temperament to a street photographer, like Henri Cartier-Bresson,” Glaser notes, paraphrasing the quote Cartier-Bresson gave to the Washington Post in 1957: “There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative,” he said. “Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.” [In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his book Images à la sauvette, whose English edition was titled The Decisive Moment. In the book’s 4,500-word preface, Cartier-Bresson reproduced text from the 17th century Cardinal de Retz, who said, “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.” Cartier-Bresson applied this to his photographic style, contending that “photography is simultaneously and instantaneously the recognition of a fact and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that express and signify that fact.”]

Because of the environmental content, depth and resolution of her images, it is tempting to draw comparisons between Glaser’s work and that of Ansel Adams. “I’m closer in temperament to a street photographer, like Henri Cartier-Bresson,” Glaser notes, paraphrasing the quote Cartier-Bresson gave to the Washington Post in 1957: “There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative,” he said. “Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.” [In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his book Images à la sauvette, whose English edition was titled The Decisive Moment. In the book’s 4,500-word preface, Cartier-Bresson reproduced text from the 17th century Cardinal de Retz, who said, “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.” Cartier-Bresson applied this to his photographic style, contending that “photography is simultaneously and instantaneously the recognition of a fact and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that express and signify that fact.”]

The theme that unifies all of Glaser’s images is the desire to “show [viewers] what [they] haven’t seen” before. Each sensuous image affords a moment of awareness, reflection and introspection and conveys the mystery and primal power of this environment in a unique and personal view that is simultaneously unfamiliar, alluring and visceral. She evokes this otherworldly aquatic realm as no other photographer has done before.

The theme that unifies all of Glaser’s images is the desire to “show [viewers] what [they] haven’t seen” before. Each sensuous image affords a moment of awareness, reflection and introspection and conveys the mystery and primal power of this environment in a unique and personal view that is simultaneously unfamiliar, alluring and visceral. She evokes this otherworldly aquatic realm as no other photographer has done before.

As Ms. Glaser sums up in her Artist Statement, “[t]he mystery of these waters and the complicated puzzle of their continued existence inspires these pictures and continues to summon us to look even deeper.”

Fast Facts.

The Anna Lamar Switzer Center of the Visual Arts in Pensacola named Glaser their 2013 Distinguished Artist, an honor they accorded in 2011 to Christo and Jean-Claude.

The Anna Lamar Switzer Center of the Visual Arts in Pensacola named Glaser their 2013 Distinguished Artist, an honor they accorded in 2011 to Christo and Jean-Claude. - The Anna Lamar Switzer Center for the Visual Arts also exhibited Glaser’s Mark of Water show in 2013.

The Harn Museum of Art in Gainesville, Florida will host The Mark of Water from February 11 through July 6, 2014.

The Harn Museum of Art in Gainesville, Florida will host The Mark of Water from February 11 through July 6, 2014.- Glaser’s photography will also be included by Sanibel’s Watson MacRae Gallery in its Landscapes: A Different View exhibition, which opens on February 11, 2014.

Related Articles and Links.

http://www.karenglaserphotography.com

http://www.karenglaserphotography.com- Underwater photographer Karen Glaser coming to Sanibel’s Watson MacRae Gallery (01-30-14)

- Photos by underwater photographer Karen Glaser on permanent display at FGCU (06-22-12)

- FGCU proud to display images by prestigious underwater photographer Karen Glaser (06-22-12)

- Photographer Glaser brings back unique images from remote, dangerous places (06-22-12)

- Spotlight on Karen Glaser and ‘Mark of Water’ exhibit at Rauschenberg Gallery – 1 (10-29-11)

- Spotlight on Karen Glaser and ‘Mark of Water’ exhibit at Rauschenberg Gallery – 2 (10-29-11)

- Spotlight on Karen Glaser and ‘Mark of Water’ exhibit at Rauschenberg Gallery – 3 (10-29-11)

- Reception tomorrow night at Bob Rauschenberg for photographer Karen Glaser (10-27-11)

- Profiling Bob Rauschenberg Gallery photography exhibitor Karen Glaser (10-07-11)

- Underwater photography exhibit opens at Bob Rauschenberg Gallery October 28 (10-07-11)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

The most fantastic photos of the springs and rivers I have ever seen..