For actor-screenwriter-playwright Derek Lively, it’s all a matter of intentionality

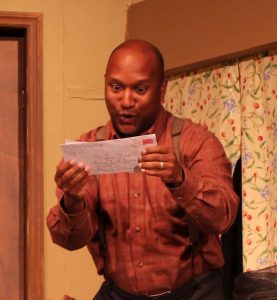

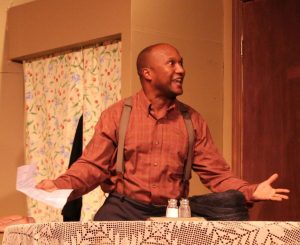

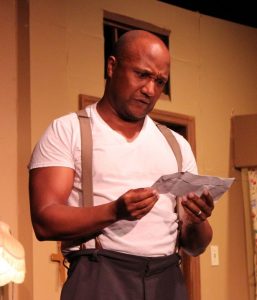

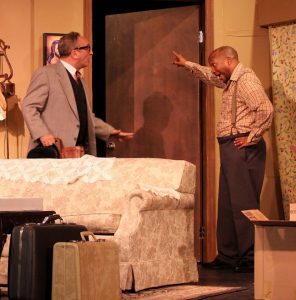

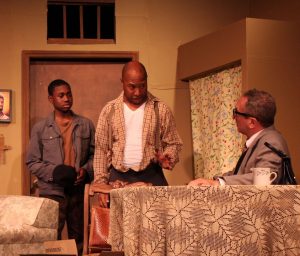

Southwest Florida theater-goers are still raving about Derek Lively’s portrayal of Walter Lee Younger in Theatre Conspiracy’s recent production of Lorraine Hanberry’s masterwork, A Raisin in the Sun. It was his best role to date, but not his first “tour d’force” performance. That appellation was employed by a theater critic nearly 20 years ago as well – then, to describe his performance in Dreamin’ in Church, a one-actor dramedy by playwright Robert O’Hara that was part of Worth Street Theater Company’s Snapshots 2000. In spite of a nearly 18-year hiatus, it would seem, the veteran actor has barely missed a step.

Southwest Florida theater-goers are still raving about Derek Lively’s portrayal of Walter Lee Younger in Theatre Conspiracy’s recent production of Lorraine Hanberry’s masterwork, A Raisin in the Sun. It was his best role to date, but not his first “tour d’force” performance. That appellation was employed by a theater critic nearly 20 years ago as well – then, to describe his performance in Dreamin’ in Church, a one-actor dramedy by playwright Robert O’Hara that was part of Worth Street Theater Company’s Snapshots 2000. In spite of a nearly 18-year hiatus, it would seem, the veteran actor has barely missed a step.

If you’re not familiar with Worth Street Theater, it produced shows at New York’s Joseph Papp Public  Theater, Samuel Beckett Theatre and Tribeca Playhouse. By the turn of the century, Lively had been prominent in the Manhattan theater scene for more than 20 years, with over 40 productions to his credit over that span. He was regularly seen at regional and Off-Broadway venues. In addition to Public Theater and Samuel Beckett, he also took the boards at La Mama Experimental Theatre Club in the East Village, where emerging artists learn from established artists and where artists from around the globe share work and ideas.

Theater, Samuel Beckett Theatre and Tribeca Playhouse. By the turn of the century, Lively had been prominent in the Manhattan theater scene for more than 20 years, with over 40 productions to his credit over that span. He was regularly seen at regional and Off-Broadway venues. In addition to Public Theater and Samuel Beckett, he also took the boards at La Mama Experimental Theatre Club in the East Village, where emerging artists learn from established artists and where artists from around the globe share work and ideas.

Although his degree  is in business management and economics, he went to acting school in New York. “I had some really well-known teachers,” teases Derek, who finally drops the names of Arthur French and Salem Ludwig. He also studied at Herbert Berghof’s HB Studio. One of New York’s original acting ateliers, HB supports vigorous, lifelong practice in theater based on a solid foundation of practical training.

is in business management and economics, he went to acting school in New York. “I had some really well-known teachers,” teases Derek, who finally drops the names of Arthur French and Salem Ludwig. He also studied at Herbert Berghof’s HB Studio. One of New York’s original acting ateliers, HB supports vigorous, lifelong practice in theater based on a solid foundation of practical training.

“And in addition to my classes,  I would run to Lincoln Center every weekend and soak up everything I could possibly learn. I would study productions at the Gilbert, the Simon, the Hackett and the [70-seat] Gene Frankel down on Bond Street. Frankel was the first person to direct an all-black cast – I think it included James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson and Roscoe Lee Browne.” Louis Gossett Jr. and Maya Angelou were also members of that cast, which ran for more than three

I would run to Lincoln Center every weekend and soak up everything I could possibly learn. I would study productions at the Gilbert, the Simon, the Hackett and the [70-seat] Gene Frankel down on Bond Street. Frankel was the first person to direct an all-black cast – I think it included James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson and Roscoe Lee Browne.” Louis Gossett Jr. and Maya Angelou were also members of that cast, which ran for more than three  years, toured Europe and led to Frankel’s third Obie award.

years, toured Europe and led to Frankel’s third Obie award.

“I was doing pretty well with stage work and had a solo show that was well-received,” he reminisces, referring to Welcome to My Soul, which he wrote and performed at HERE as part of PSNBC’s talent showcase for NBC executives, leading to a first-look development deal with Universal.

But he put so  much of himself into both his acting and the solo show that he decided he needed a break, so he stepped away from theater to focus on screenwriting for a while.

much of himself into both his acting and the solo show that he decided he needed a break, so he stepped away from theater to focus on screenwriting for a while.

It was an inevitable step in the actor/playwright’s creative evolution. After all, in addition to acting, he had studied writing at the New York’s esteemed Playwright’s Horizon. Affiliated with NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts on Lafayette Street, Playwrights Horizon is a writer’s theater dedicated to the support and development of contemporary American playwrights,  composers and lyricists – and to the production of their new work. Since its founding, Playwrights Horizons has produced numerous groundbreaking Pulitzer, Tony, Olivier and Obie award winning plays and musicals, including The Flick, Clybourne Park, Grey Gardens, I Am My Own Wife, Violet, The Heidi Chronicles, Driving Miss Daisy, Once on This Island, and Sunday in the Park with George.

composers and lyricists – and to the production of their new work. Since its founding, Playwrights Horizons has produced numerous groundbreaking Pulitzer, Tony, Olivier and Obie award winning plays and musicals, including The Flick, Clybourne Park, Grey Gardens, I Am My Own Wife, Violet, The Heidi Chronicles, Driving Miss Daisy, Once on This Island, and Sunday in the Park with George.

Applying the same fervidness  that characterized his acting, Lively met with quite a bit of success in playwriting and screenwriting as well. His play, Two Realities, was the co-winner of the Around the Block 2006 Short Play Reading Series and was a semi-finalist in the American Globe Theatre’s Fifteen Minute Play Festival. His screenplay, The Nigga, was the winner of the 2008 Hollywood Black Film Festival Storyteller Competition and was subsequently optioned by Harrison Reiner, production executive for the Academy Award-winning films My Left Foot and Cinema Paradiso. And he was invited to participate in the HBO Writers’ Lab sponsored by the American Black Film Festival.

that characterized his acting, Lively met with quite a bit of success in playwriting and screenwriting as well. His play, Two Realities, was the co-winner of the Around the Block 2006 Short Play Reading Series and was a semi-finalist in the American Globe Theatre’s Fifteen Minute Play Festival. His screenplay, The Nigga, was the winner of the 2008 Hollywood Black Film Festival Storyteller Competition and was subsequently optioned by Harrison Reiner, production executive for the Academy Award-winning films My Left Foot and Cinema Paradiso. And he was invited to participate in the HBO Writers’ Lab sponsored by the American Black Film Festival.

Then, three years ago, Derek and his wife decided they needed a change of climate. So they left their native New York for the land of sun, fun and palm trees. It took him a couple of years to acclimate to the area, but he was already assessing the theater scene here in Southwest Florida even before he departed New York. When Bill Taylor and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance for the Arts decided to produce August Wilson’s Seven Guitars, he decided to come out of his self-imposed semi-retirement and audition for the play. Sonya McCarter cast him in the role of Canewell.

Then, three years ago, Derek and his wife decided they needed a change of climate. So they left their native New York for the land of sun, fun and palm trees. It took him a couple of years to acclimate to the area, but he was already assessing the theater scene here in Southwest Florida even before he departed New York. When Bill Taylor and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance for the Arts decided to produce August Wilson’s Seven Guitars, he decided to come out of his self-imposed semi-retirement and audition for the play. Sonya McCarter cast him in the role of Canewell.

“I never really stopped acting,” Lively remarks off-handedly. But he acknowledges that it still took some time for him to mesh mentally, emotionally and physically all the same. Perhaps, but his performance was strong, powerful and confident. Hell, he even learned to play the harmonica for the role.

“I never really stopped acting,” Lively remarks off-handedly. But he acknowledges that it still took some time for him to mesh mentally, emotionally and physically all the same. Perhaps, but his performance was strong, powerful and confident. Hell, he even learned to play the harmonica for the role.

“It’s like riding a bike,” Derek shrugs. “You never forget it. You still know what to do because you’re a professional.”

In the latter regard, he’s a member in good standing of both the Actor’s Equity Association and SAG-AFTRA.

“But it takes time to get back into condition,  to get your timing, rhythm and awareness back,” he concedes. “By the end of the run, I felt like I finally got my sea legs.”

to get your timing, rhythm and awareness back,” he concedes. “By the end of the run, I felt like I finally got my sea legs.”

And just a handful of months later, he followed his supporting role as Canewell with the lead in A Raisin in the Sun.

“It was amazing to do August Wilson and Lorraine Hansberry  in a single season. But [Canewell and Walter Lee Younger are] two very different types of roles. With Canewell, it’s kind of like Shakespeare; you work from the outside in, letting the poetry of the text guide what you’re feeling internally,” Derek explains. “With Hansberry, you have to work from the inside out. Even though it’s beautifully written, there is so much going on with the character that you really have to peel the layers like an onion to find out what’s going on inside. [Director] Sonya [McCarter] did a great job of providing a roadmap to knowing this sort

in a single season. But [Canewell and Walter Lee Younger are] two very different types of roles. With Canewell, it’s kind of like Shakespeare; you work from the outside in, letting the poetry of the text guide what you’re feeling internally,” Derek explains. “With Hansberry, you have to work from the inside out. Even though it’s beautifully written, there is so much going on with the character that you really have to peel the layers like an onion to find out what’s going on inside. [Director] Sonya [McCarter] did a great job of providing a roadmap to knowing this sort  of person and allowing that to shape the character.”

of person and allowing that to shape the character.”

In lesser hands, there’s the danger that the audience might perceive Walter as an entitled, self-absorbed middle-aged guy who just screams a lot. The key to infusing the character with the depth and dimensionality that Hansberry intended is a fundamental appreciation that Walter’s anger emanates from fear, anguish and a cognizance of his own mortality. Not only is life passing him by without him achieving the success he deserves in his own mind, his job as a chauffeur requires him to squire around those who have achieved the success he  knows he’s capable of attaining if he could just catch a break.

knows he’s capable of attaining if he could just catch a break.

“When I picked up the script and started reading it, I said, ‘Oh yeah, I get this,’ which goes back to working from the inside out,” says Lively. “Sometimes you connect to material on a very organic level. It just hits you and you really relate to the character.  You don’t have to figure out the character because you know the character at heart.”

You don’t have to figure out the character because you know the character at heart.”

While Derek has achieved a great deal over the course of his career and been showered with favorable reviews, accolades and awards, he’s also experienced the disappointments that are inevitable in the performance arts.  He’s had brief flirtations with Hollywood, and had his soul zapped after laying it all out there a time or two. Harder to take, though, is seeing some of his contemporaries from the New York theater scene make it on television even though he has talent equal to, or more

He’s had brief flirtations with Hollywood, and had his soul zapped after laying it all out there a time or two. Harder to take, though, is seeing some of his contemporaries from the New York theater scene make it on television even though he has talent equal to, or more  formidable than, theirs.

formidable than, theirs.

“So I get what’s eating at Walter,” Derek says quietly. “He knows he could be just as successful [as the people he chauffeurs around], but he’s been held back and now senses that his life slipping away.”

Most people readily admit that getting a break at the right time is instrumental in achieving great success. Lively agrees, but he defines luck as opportunity meeting preparation. And sometimes you just have to make your own breaks to get what  and where you want.

and where you want.

“It’s all about how strong your intentionality is. If your intentionality is very strong, you’ll figure it out.”

And Lively’s intention is to strive for new heights in acting, playwriting, screenwriting – and even directing and producing – here in Southwest Florida. “This is home now,” he says without hesitation.

Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance for the Arts is likely to figure prominently into Lively’s future. “[Producing Artistic Director] Bill [Taylor] and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance are devoting their time to doing plays by and with people of color – as opposed to plays that have people of color in clichéd roles like maids or gardeners. As a result, you’re starting to see a set of artists grow and develop there. Sonya [McCarter] and Bill are [laying the foundation] for something that could eventually be really, really exciting. Time will tell.”

Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance for the Arts is likely to figure prominently into Lively’s future. “[Producing Artistic Director] Bill [Taylor] and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance are devoting their time to doing plays by and with people of color – as opposed to plays that have people of color in clichéd roles like maids or gardeners. As a result, you’re starting to see a set of artists grow and develop there. Sonya [McCarter] and Bill are [laying the foundation] for something that could eventually be really, really exciting. Time will tell.”

And other venues  are taking notice of the progress that Theatre Conspiracy is making in this direction. “Florida Rep is doing Fences this season, and Laboratory Theater is doing Anna in the Tropics, which contemplates an all Latin cast written by a Latino playwright who won a Pulitzer.”

are taking notice of the progress that Theatre Conspiracy is making in this direction. “Florida Rep is doing Fences this season, and Laboratory Theater is doing Anna in the Tropics, which contemplates an all Latin cast written by a Latino playwright who won a Pulitzer.”

For its part, Theatre Conspiracy will celebrate its 25th consecutive season with productions of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (its third play from playwright August Wilson’s  Century Cycle exploring the African-American experience in America on a decade-by-decade basis) and The Agitators (the story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass).

Century Cycle exploring the African-American experience in America on a decade-by-decade basis) and The Agitators (the story of Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass).

Lively also plans to continue to do both playwriting and screenwriting, and won’t rule out acting, directing and even producing independent film. “I don’t like to put any limitations on myself, so I’m definitely going to explore any ideas that may pop into my head.”

He’d also like to do another one-man show. But he’d especially like to get back into Shakespeare. Hamlet and Richard III would be dreams come true.

He’d also like to do another one-man show. But he’d especially like to get back into Shakespeare. Hamlet and Richard III would be dreams come true.

“If you can do Shakespeare, you can do anything,” Derek avers. “It’s always great to make Shakespeare part of the cultural experience in any community.”

In fact, Lively would like to do  what Joe Papp did with The Public Theater in bringing theater to the people. It’s a lofty but laudable goal. Since its founding more than 60 years ago, The Public has produced a wide range of accessible programming, including Shakespeare in the Park, The Mobile Unit touring throughout New York City’s five boroughs and both the Public Forum and Under the Radar.

what Joe Papp did with The Public Theater in bringing theater to the people. It’s a lofty but laudable goal. Since its founding more than 60 years ago, The Public has produced a wide range of accessible programming, including Shakespeare in the Park, The Mobile Unit touring throughout New York City’s five boroughs and both the Public Forum and Under the Radar.

Sometimes  leaving a place like New York is good for a person.

leaving a place like New York is good for a person.

Sometimes it’s also good for the place to which that person moves.

Time will tell.

But odds are good that this thoughtful, intelligent, ambitious actor,  playwright, screenwriter and director will leave his mark here in Southwest Florida. It’s a matter of intentionality.

playwright, screenwriter and director will leave his mark here in Southwest Florida. It’s a matter of intentionality.

May 21, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ considered one of 20th Century’s greatest plays

- ‘Raisin in the Sun’ a race relations conversation starter

Without role models, mentors and sponsors, dreams shrivel like ‘A Raisin in the Sun’

Without role models, mentors and sponsors, dreams shrivel like ‘A Raisin in the Sun’- ‘Raisin in the Sun’ actor Patricia Idlette in the spotlight

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ actor Cantrella Canady in the spotlight

- Spotlight on ‘Raisin in the Sun’ actor Rose Thomas and her character Beneatha

- Spotlight on ‘Raisin in the Sun’ actor Keehnon Jackson

- Spotlight on ‘Raisin in the Sun’ actor Kenneth Jones

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ actor James Robinson in the spotlight

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ actor Sandra Dixon in the spotlight

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ play dates, times and ticket info

- Community talk-backs to follow two ‘Raisin in the Sun’ performances

- ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ director Sonya McCarter in the spotlight

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.