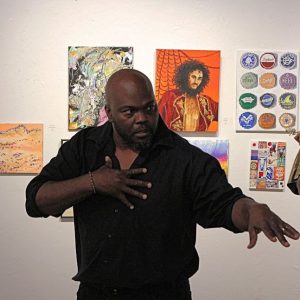

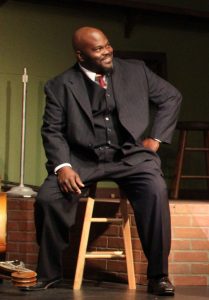

Cicero McCarter just happy to work with, learn from and be around other actors

Cicero McCarter did not come to theater in the normal way. He didn’t perform from the time he could walk, and didn’t study theater in high school or college. He didn’t get prodded or pressured into tackling a role in an August Wilson play by his actor/director wife Sonya. Heck, he didn’t even attend or graduate from the Alliance’s CHANGE program. He actually took his first fledgling steps at his church, performing in skits and short one-act plays that his mother-in-law wrote and his wife directed.

Cicero McCarter did not come to theater in the normal way. He didn’t perform from the time he could walk, and didn’t study theater in high school or college. He didn’t get prodded or pressured into tackling a role in an August Wilson play by his actor/director wife Sonya. Heck, he didn’t even attend or graduate from the Alliance’s CHANGE program. He actually took his first fledgling steps at his church, performing in skits and short one-act plays that his mother-in-law wrote and his wife directed.

“One was called Christmas in the Neighborhood, which we performed at the S.T.A.R.S. Complex,” Cicero recalls. “It was packed and  people really loved it. I felt like I was on the other side of the movie. You know how you talk to a movie screen or your TV? Well, people were actually doing that kind of stuff during the play, and it was kind of fun trying to hold character as people in the audience were doing that at the same time. My wife said, ‘You know, if you really want to try your hand at some real theater, you can audition at the Alliance. I did. And I got a part in Toys in the Attic.”

people really loved it. I felt like I was on the other side of the movie. You know how you talk to a movie screen or your TV? Well, people were actually doing that kind of stuff during the play, and it was kind of fun trying to hold character as people in the audience were doing that at the same time. My wife said, ‘You know, if you really want to try your hand at some real theater, you can audition at the Alliance. I did. And I got a part in Toys in the Attic.”

That was an eye-popping experience. Besides Cicero,  the cast which Director Stephanie Davis assembled for that show included Rachel Burttram, Karen Goldberg, Jason Drew and Elvis Mortley.

the cast which Director Stephanie Davis assembled for that show included Rachel Burttram, Karen Goldberg, Jason Drew and Elvis Mortley.

“They are really, really good, and I was hooked.”

Not just by the rush of adrenaline and the exhiliration of applause. Cicero liked watching, learning from and just being around the other actors. And it’s been that way with each play he’s subsequently done.

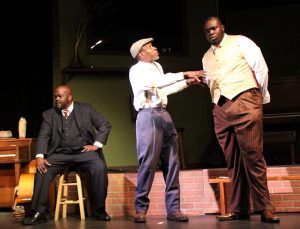

“Working with and taking notes from fellow cast members is great,” Cicero amplifies. “Thomas Marsh,  dang, that guy be anyone, from a talking pig to [Joseph Merrick] The Elephant Man. don’t even have to tell you how good Cantrella is. Or Derek Lively. When I’m sitting quietly backstage and they’re talking, I’m listening and just soaking it all in, trying to get better. If I’m going to do it, I want to get better each time I do.”

dang, that guy be anyone, from a talking pig to [Joseph Merrick] The Elephant Man. don’t even have to tell you how good Cantrella is. Or Derek Lively. When I’m sitting quietly backstage and they’re talking, I’m listening and just soaking it all in, trying to get better. If I’m going to do it, I want to get better each time I do.”

Besides his interactions with his fellow cast mates, McCarter relishes seeing how the production comes together and turns out.

“From the time  they we get together and read the play for the first time to the opening, it’s a journey. Just seeing characters come alive, it’s a lot of fun. I didn’t think I was going to enjoy it as much as I do.”

they we get together and read the play for the first time to the opening, it’s a journey. Just seeing characters come alive, it’s a lot of fun. I didn’t think I was going to enjoy it as much as I do.”

In fact, he loves just about everything theater. Everything, that is, except for memorizing his lines.

“That’s been hard on me,” he confesses. “I’m not a young guy.”

He admits to having the “actor’s nightmare” more than occasionally. That’s the dream many performers have in which they’re on stage, typically on opening night, and cannot remember any of their lines.

typically on opening night, and cannot remember any of their lines.

“A couple of times it happened for real,” he jokes. “But it’s funny how by the time you get on stage, the lines just come to you based on where you’re standing and what you’re doing. The stage directions really help a lot [with the memorization].”

Every actor develops their own technique for memorizing their lines.

Some simply read the script over and over again in much the same way you learned the lyrics to a song on the radio as a kid. Others use a sheet of scrap paper to cover over everything but the line they’re memorizing and the one before it (the cue line). Many walk while memorizing because the activity assists in the process in some undefined way. And a lot of actors take a power nap immediately after memorizing a chunk

Some simply read the script over and over again in much the same way you learned the lyrics to a song on the radio as a kid. Others use a sheet of scrap paper to cover over everything but the line they’re memorizing and the one before it (the cue line). Many walk while memorizing because the activity assists in the process in some undefined way. And a lot of actors take a power nap immediately after memorizing a chunk  of dialogue because somehow the brain processes short-term memory and pushes all the new information into long-term recall.

of dialogue because somehow the brain processes short-term memory and pushes all the new information into long-term recall.

One popular mnemonic device that many actors use involves writing down the first letter of each word in the line. For example, “Look, I don’t want to assume anything about him” is LIDWTAAAH. If you jot that down on a piece of scrap paper and look at it when you finish reading this article, I’ll be you’ll also remember the line of dialogue!

There’s also the “memory palace”  or “body parts” technique, where information is stored in a mental room or on body parts. This is the method espoused years ago by the Mega Memory guy, Kevin Trudeau.

or “body parts” technique, where information is stored in a mental room or on body parts. This is the method espoused years ago by the Mega Memory guy, Kevin Trudeau.

And, of course, there are those who write their lines on index cards. The science behind that is interesting. Last month (May, 2020),  Scientific American published research that found that “students who write out their notes on paper or index cards actually learn more” than those who use a laptop.

Scientific American published research that found that “students who write out their notes on paper or index cards actually learn more” than those who use a laptop.

Running lines with someone else helps you not only learn your lines, but listen to what the other character is  saying in the scene. There’s even an app called Rehearser that works as a digital scene partner. “You record all the lines, and then it will read your partner’s dialogue back to you and give you a beep when it’s your turn to speak. And if you need help, you can tap the screen, and it’ll show you what your line is. It’s so helpful for those quick turnarounds for commercial auditions.”

saying in the scene. There’s even an app called Rehearser that works as a digital scene partner. “You record all the lines, and then it will read your partner’s dialogue back to you and give you a beep when it’s your turn to speak. And if you need help, you can tap the screen, and it’ll show you what your line is. It’s so helpful for those quick turnarounds for commercial auditions.”

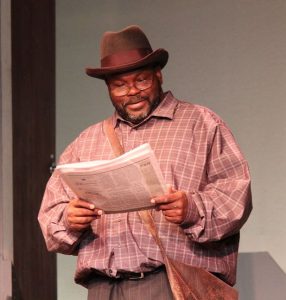

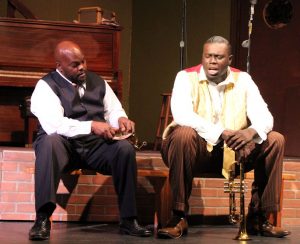

Of course, it doesn’t help that McCarter’s been a mainstay in the plays of August Wilson, a playwright known not only for wordiness, but a type of prose that, like Shakespeare, taxes the ability of actors to memorize the dialogue he writes. [He was Canewell (Stool Pigeon) in King Hedley II, Bynum Walker in Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Hedley in Seven Guitars and Slow  Drag in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.]

Drag in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.]

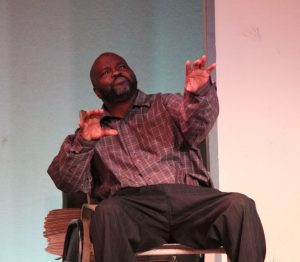

“Honestly, it’s one reason I like doing staged readings. It takes the pressure off learning lines and blocking. With staged readings, it is more about the words coming off the page and the feeling behind them than it is about all the movement that’s involved in a stage play. It’s not necessarily easier, but it’s less stressful.”

As with most decisions in life,  there are advantages and disadvantages associated with staged readings in lieu of full productions.

there are advantages and disadvantages associated with staged readings in lieu of full productions.

“The downside is that you don’t get as close to your castmates and the camaraderie is one of the things I like most about acting in a stage play.”

And the after-party, Cicero quickly amends.

“It’s not like that. We’re not swinging from chandeliers or anything.  But there’s this sense of elation that comes with that first performance in front of a live audience after six, eight weeks of table reads and rehearsals.”

But there’s this sense of elation that comes with that first performance in front of a live audience after six, eight weeks of table reads and rehearsals.”

By the time a show opens, cast and crew have generally bonded as family, and their sense of euphoria following that opening night performance is as  palpable as high school or college graduation.

palpable as high school or college graduation.

“The people that you’re there with, you kind of get drawn into their personal life. Somebody’s not feeling well and they’re not going make it tonight, you’re genuinely concerned not because they’re not going to be there but because it’s somebody you know now.”

Many of those  relationships continue after the production ends, and you’re likely to see many of the same faces at auditions or in your next show.

relationships continue after the production ends, and you’re likely to see many of the same faces at auditions or in your next show.

“We’re such a small community in this area. You start seeing the same people. You know what to expect from them. You know how to step up your game when you’re with them and performing with them. I like that.”

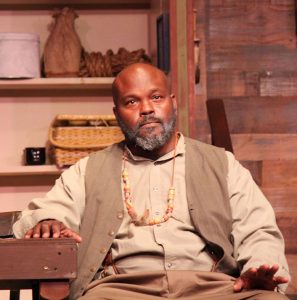

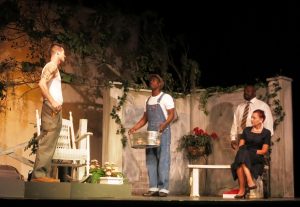

Although you’ll likely see more of Cicero in staged readings at the Alliance and elsewhere, he expects to continue to take roles in full productions. He notes wryly that there are still six more plays in August Wilson’s Pittsburgh or Century Cycle that Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance has yet to produce. And the thought of being in a musical especially intrigues Cicero.

Although you’ll likely see more of Cicero in staged readings at the Alliance and elsewhere, he expects to continue to take roles in full productions. He notes wryly that there are still six more plays in August Wilson’s Pittsburgh or Century Cycle that Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance has yet to produce. And the thought of being in a musical especially intrigues Cicero.

“There’s talk of doing a musical version of The Color Purple. I’m think it would kind of be fun to try a musical once. I’m hoping I can get a part in that. We’ll see.”

That we shall.

As folk rock composer/singer James Taylor is wont to say, “All things in the fullness of time.”

June 4, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.