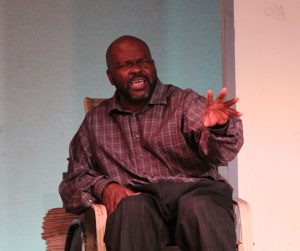

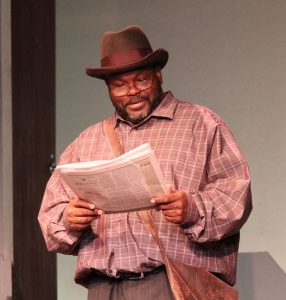

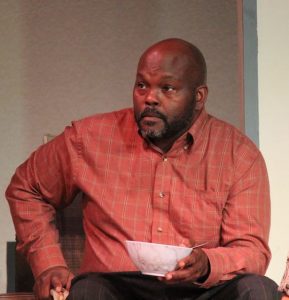

Cicero McCarter uses inner conflict to infuse August Wilson characters with depth and believability

A few years ago, Producing Artistic Director Bill Taylor and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance decided to showcase more plays written by both black and female playwrights. Since then, they’ve not only produced Mountaintop by Katori Hall, A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf by the late Ntozake Shange, but four plays from August Wilson’s Pittsburgh or Century Cycle, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Seven Guitars, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone and King Hedley II. Cicero McCarter’s been in each of those last four, and it hasn’t been easy.

A few years ago, Producing Artistic Director Bill Taylor and Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance decided to showcase more plays written by both black and female playwrights. Since then, they’ve not only produced Mountaintop by Katori Hall, A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf by the late Ntozake Shange, but four plays from August Wilson’s Pittsburgh or Century Cycle, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Seven Guitars, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone and King Hedley II. Cicero McCarter’s been in each of those last four, and it hasn’t been easy.

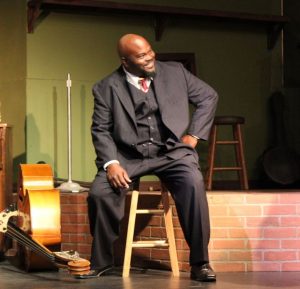

“Of all the August Wilson’s that I’ve done, Slow Drag [in Ma Rainey] was  the only character I could possibly be [in real life]. He enjoyed life. He played base fiddle. He was a cool dude,” McCarter muses.

the only character I could possibly be [in real life]. He enjoyed life. He played base fiddle. He was a cool dude,” McCarter muses.

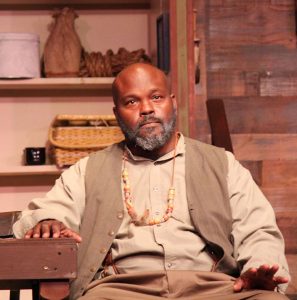

In Seven Guitars, McCarter played Hedley, an old man with tuberculosis, a religious fetish and a big knife with which he kills chickens for the sandwiches he sells. Having turned his back on the white world he loathes, he’s a believer in saints, spirits, prophets and the ghost of Charles (Buddy) Bolden, the legendary New Orleans trumpeter who died in an insane asylum.

In fact, more  than anything else, Hedley would like to sire a messiah.

than anything else, Hedley would like to sire a messiah.

“I grew up in Fort Myers and used to hang with my great-grandfather,” Cicero begins. “He’d take us hunting, and some of the crowd that he ran with were the ones who distilled moonshine. They weren’t the healthiest of people physically or mentally, but they were okay. Even with their faults, they always had something that they would say that would stick with you.”

And these figures from his past provided Cicero with a window into the mind, spirituality and ritualism practiced by his character.

But  at the same time, Hedley’s belief system sharply conflicted with McCarter’s own values, religious beliefs and personal philosophy. And, of course, he commits murder in the end.

at the same time, Hedley’s belief system sharply conflicted with McCarter’s own values, religious beliefs and personal philosophy. And, of course, he commits murder in the end.

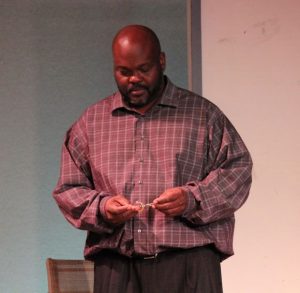

That conflict widened into a veritable chasm with in the character of Bynum Walker in Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

“He’s a root worker, but a good one. He didn’t going around putting hexes on people,” Cicero explains.

Rootwork (also known as Hoodoo and conjuring) is Southern folk magic grounded in centuries of African American heritage within the southern United States. It is a system that blends the magical technology of the Congo slaves who were taken from Africa in the slave trade with Native American herbal knowledge, bits of European folk magic and even Jewish mysticism. While most rootwork practitioners

Rootwork (also known as Hoodoo and conjuring) is Southern folk magic grounded in centuries of African American heritage within the southern United States. It is a system that blends the magical technology of the Congo slaves who were taken from Africa in the slave trade with Native American herbal knowledge, bits of European folk magic and even Jewish mysticism. While most rootwork practitioners  are Protestant Christians, they employ the Psalms and The Lord’s Prayer in aid of the spells they cast to attract money, love and protection from illness, enemies and evil. As a result, there is room in rootwork for both healing and causing sickness, for drawing blessings as well as laying down curses.

are Protestant Christians, they employ the Psalms and The Lord’s Prayer in aid of the spells they cast to attract money, love and protection from illness, enemies and evil. As a result, there is room in rootwork for both healing and causing sickness, for drawing blessings as well as laying down curses.

“But that kind of thing is seriously taboo in basic Pentecostal  Christianity, messing with that,” Cicero quickly adds. “There were some people down my street when I was younger who dabbled in stuff like that and the more you put in a thing like that, the more you make it real. If you believe in it hard enough, you make it real. And Bynum was one of those kind of people.”

Christianity, messing with that,” Cicero quickly adds. “There were some people down my street when I was younger who dabbled in stuff like that and the more you put in a thing like that, the more you make it real. If you believe in it hard enough, you make it real. And Bynum was one of those kind of people.”

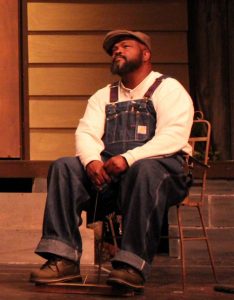

Bad enough, but then along came Canewell in King Hedley II.

The chasm morphed into a gulf.

“I’m still  trying to get over some of the things he did and said,” Cicero somberly proclaims. “He started filtering into my real life. Some of my acquaintances [who saw the show] still haven’t gotten over it.”

trying to get over some of the things he did and said,” Cicero somberly proclaims. “He started filtering into my real life. Some of my acquaintances [who saw the show] still haven’t gotten over it.”

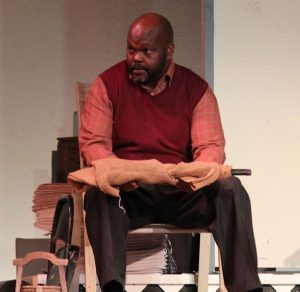

Reflective, introspective, deeply religious and very private, McCarter found himself at odds with so much of what Stool Pigeon (Canewell’s perjorative nickname)  lays down in King Hedley II. More to the point, he found it, well, disrespectul, sacriligious and downright blasphemous.

lays down in King Hedley II. More to the point, he found it, well, disrespectul, sacriligious and downright blasphemous.

“But that’s the playwright. He draws that aspect of the character out and gives it life,” Cicero concedes. “One of the themes in August Wilson’s plays is the conflict between the religious beliefs the slaves brought with them from Africa and the tenets of Christianity the slave owners thrust upon them. And honestly, Christianity was used more to enslave at that time than set them spiritually free.”

With laws in place to criminalize teaching slaves to read, plantation owners knew they could read their minions Biblical passages that seemingly provided a justification for slavery without their slaves ever finding out differently. But then they heard the story of Moses and Pharaoh and the Israelites, and the lesson they learned to the dismay and chagrin of their overseers is that God wants his people to be free.

With laws in place to criminalize teaching slaves to read, plantation owners knew they could read their minions Biblical passages that seemingly provided a justification for slavery without their slaves ever finding out differently. But then they heard the story of Moses and Pharaoh and the Israelites, and the lesson they learned to the dismay and chagrin of their overseers is that God wants his people to be free.

And then Jesus is  born and begins his ministry. For slaves, both before and following Emancipation, Jesus is a latter-day Moses, freeing people from sin and the shackles of the establishment and the strictures of the Old Testament.

born and begins his ministry. For slaves, both before and following Emancipation, Jesus is a latter-day Moses, freeing people from sin and the shackles of the establishment and the strictures of the Old Testament.

But while that may have resonated with the African-Americans that August Wilson wrote about and depicted in Ma Rainey, Seven Guitars, Joe Turner, Hedley and his other Century Cycle plays, many blacks who made their own exodus following the Civil War to places like Chicago, Pittsburgh and other northern cities  questioned how their ancestors could not only accept but embrace the God of their enslavers.

questioned how their ancestors could not only accept but embrace the God of their enslavers.

“Black church culture is still enslaved by a lot of erroneous teachings that were taken from the Bible, from Scripture, and misused and mishandled, and it’s hard to get away from that. But everybody has their own road to travel. You can’t be somebody that you’re not just because they say you should be.”

While McCarter’s  understanding of this dynamic on an intellectual, spiritual and visceral plane uniquely enables him to portray this tension between the old African-based beliefs and New World Christian principles, it exacerbates his own internal conflict and turmoil in having to speak the words that Bynum, Hedley and Stool Pigeon say in Seven Guitars, Joe Turner and King Hedley II.

understanding of this dynamic on an intellectual, spiritual and visceral plane uniquely enables him to portray this tension between the old African-based beliefs and New World Christian principles, it exacerbates his own internal conflict and turmoil in having to speak the words that Bynum, Hedley and Stool Pigeon say in Seven Guitars, Joe Turner and King Hedley II.

“Honestly, it’s hard for me to explain how I feel while I’m doing it.  I know when I’m on stage I need to look and sound as convincing as possible, but inside as I’m saying [my lines], I’m cringing. I’m cringing when I say a lot of the things that I’m saying.”

I know when I’m on stage I need to look and sound as convincing as possible, but inside as I’m saying [my lines], I’m cringing. I’m cringing when I say a lot of the things that I’m saying.”

While it’s generally the overarching goal of every actor to merge and become one with his character, McCarter uses the conflict between his own beliefs and values and those of his characters to infuse them with a level of depth and believability that’s otherwise impossible to achieve.

More, this dichotomy also enables Cicero to give voice to the very incongruity that August Wilson is trying to express through both his plays and his characters. It doesn’t work against him, but for him. As a result, both the quality of the production and the audience members who see the shows benefit at McCarter’s expense.

More, this dichotomy also enables Cicero to give voice to the very incongruity that August Wilson is trying to express through both his plays and his characters. It doesn’t work against him, but for him. As a result, both the quality of the production and the audience members who see the shows benefit at McCarter’s expense.

“One thing I did focus on to reconcile myself to Stool Pigeon is to think about who the Apostles were,” Cicero suddenly interjects. “They were fishermen. And no doubt when they saw [Jesus] do  some of the miracles that he performed, the things that came out of their mouth were probably not the kind of things you’d say when referring to God. ‘What the bleep?’ But while Jesus hung with the rougher elements of society and was probably exposed to a more vernacular manner of expression, our church members are not.”

some of the miracles that he performed, the things that came out of their mouth were probably not the kind of things you’d say when referring to God. ‘What the bleep?’ But while Jesus hung with the rougher elements of society and was probably exposed to a more vernacular manner of expression, our church members are not.”

And so McCarter’s internal conflict deepens and widens.

But August Wilson can help out with this.

“Go to Aunt Ester. She will take care of you.”

Throughout the Century Cycle, Aunt Ester helps people get their souls washed, cleanse themselves of guilt, and get rid of the weight of the past so that they can move ahead, run toward the finish line of redemption.

Throughout the Century Cycle, Aunt Ester helps people get their souls washed, cleanse themselves of guilt, and get rid of the weight of the past so that they can move ahead, run toward the finish line of redemption.

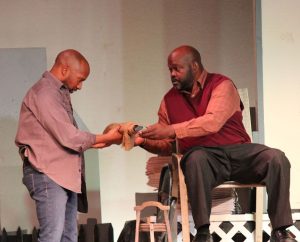

Of course, Hedley II is the play in which Aunt Ester dies, at 366 years of age, from the grief of her children forgetting their history and assimilating into  their white communities. And it’s Cicero’s character, Stool Pigeon, who not only announces her death, but that she’s coming back. It’s an allusion to Good Friday and the death of a son by his mother’s gun. It symbolizes the sacrifice of one for the salvation of many.

their white communities. And it’s Cicero’s character, Stool Pigeon, who not only announces her death, but that she’s coming back. It’s an allusion to Good Friday and the death of a son by his mother’s gun. It symbolizes the sacrifice of one for the salvation of many.

Through the sacrifices he makes in order to portray the characters he’s played, Cicero McCarter is helping all of us – black, white, red and Latinx – to understand the cost and the dangers associated with giving up who we are in order to follow someone  else’s path. And with that hopefully comes a fuller comprehension of the arrogance and the folly of demanding that people – whether they trace their lineage to Africa or are new to our soil – give up their identity, their language and their past and assimilate into our society. Instead, we should be encouraging them to retain heritage, perspectives and ways of

else’s path. And with that hopefully comes a fuller comprehension of the arrogance and the folly of demanding that people – whether they trace their lineage to Africa or are new to our soil – give up their identity, their language and their past and assimilate into our society. Instead, we should be encouraging them to retain heritage, perspectives and ways of life so that they can enrich, expand and diversify our thinking, our culture and our collective quality of life.

life so that they can enrich, expand and diversify our thinking, our culture and our collective quality of life.

If COVID-19 has taught us nothing else, it has underscored that we truly are all in this together.

May 29, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.