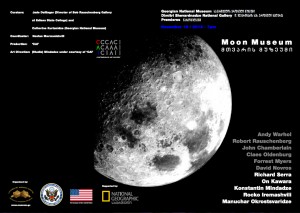

Moon Museum Exhibition

“It was breathing now half asleep. Relaxing with fuelling. The moon rose. My head said for the first time, the moon was going to have company.” Robert Rauschenberg (1969)

ON THIS PAGE YOU WILL FIND ARTICLES ABOUT THE MOON MUSEUM EXHIBITION.

**************************************************************************************

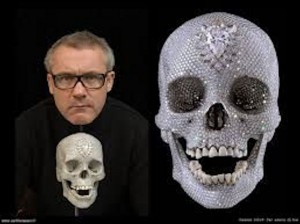

Damien Hirst and Stephen Little may be the first and only artists to land art on Mars (09-07-14)

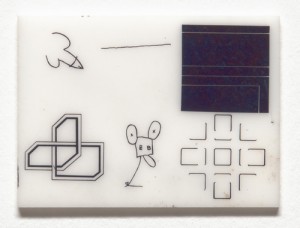

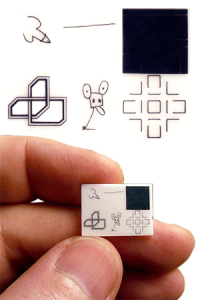

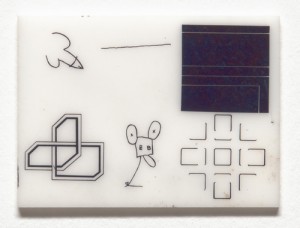

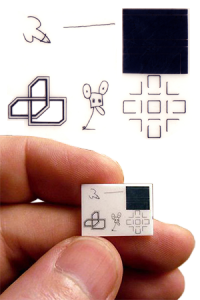

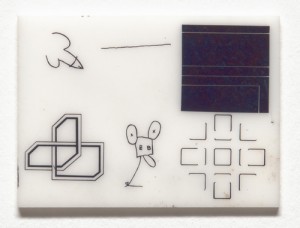

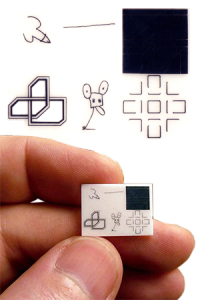

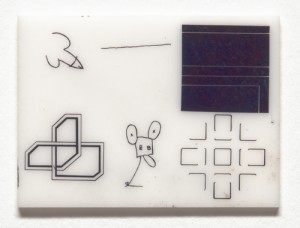

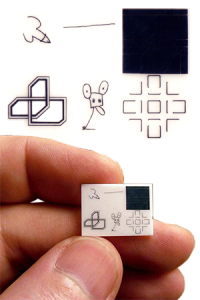

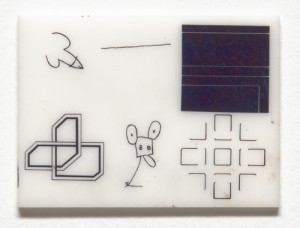

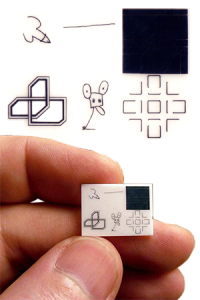

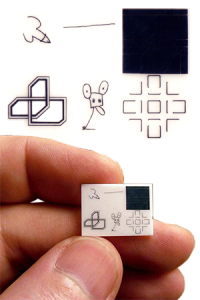

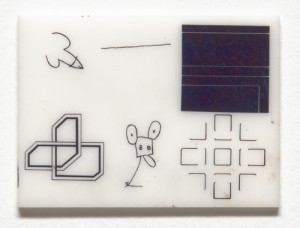

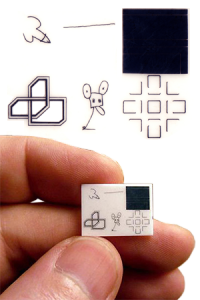

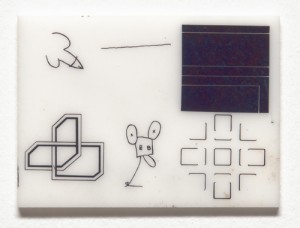

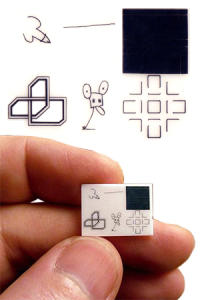

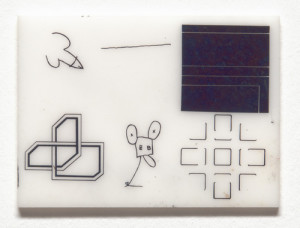

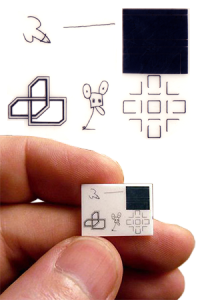

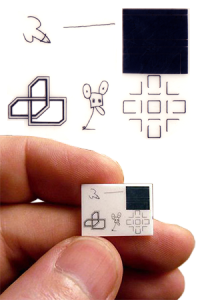

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission is on view now through September 27 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The museum consists of a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. Along with Belgian artist Paul van

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission is on view now through September 27 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The museum consists of a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. Along with Belgian artist Paul van  Hoeydonck (see next article on this page), they are the only artists who have work on the Moon, and that may be true for the foreseeable future. But two artists may have landed artwork on Mars.

Hoeydonck (see next article on this page), they are the only artists who have work on the Moon, and that may be true for the foreseeable future. But two artists may have landed artwork on Mars.

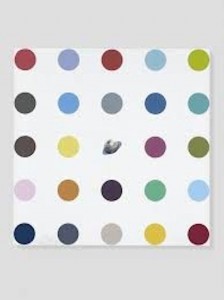

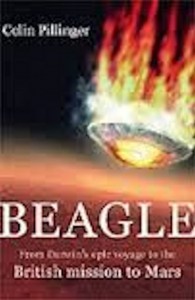

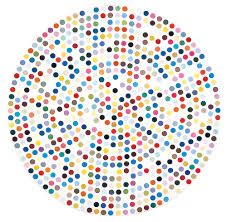

On June 2, 2003, the European Space Agency launched the Mars Express, an orbiter that included a lander named The Beagle 2 (named in tribute to the ship that twice carried Charles  Darwin during the expeditions (to the Galapagos Islands and other destinations) that ultimately lead to the theory of natural selection). Bolted to the lander was a 3-by-3-inch aluminum plate containing a painting consisting of 16 multi-colored spots that, on cursory glance, resembled a child’s watercolor box. Created by artist Damien Hirst, this spot painting also had a functional purpose. The aluminum plate was designed to calibrate the lander’s X-ray equipment. The colors Hirst included in the painting were chosen to

Darwin during the expeditions (to the Galapagos Islands and other destinations) that ultimately lead to the theory of natural selection). Bolted to the lander was a 3-by-3-inch aluminum plate containing a painting consisting of 16 multi-colored spots that, on cursory glance, resembled a child’s watercolor box. Created by artist Damien Hirst, this spot painting also had a functional purpose. The aluminum plate was designed to calibrate the lander’s X-ray equipment. The colors Hirst included in the painting were chosen to  check and calibrate the lander’s camera. And the minerals in the pigment were supposed to correct the sensor measuring the soil’s iron content.

check and calibrate the lander’s camera. And the minerals in the pigment were supposed to correct the sensor measuring the soil’s iron content.

Beagle 2 began its descent to the Martian surface on Christmas morning, 2003. A safe and successful landing necessitated three interrelated steps. First, friction from the Martian atmosphere had to slow Beagle 2 to a  pre-determined target speed. At that point, sensors within Beagle 2 would deploy parachutes to further slow the lander’s descent. Then, at about a mile above the surface, large gas bags would inflate to cushion the landing as Beagle 2 bounced along the red planet’s surface. After Beagle 2 finally came to rest, the gas bags were to deflate, allowing the top of the lander to open, thereby exposing four solar array disks and a UHF antenna. The latter was programmed to send a signal (and possibly an image of the Martian surface) back to Earth.

pre-determined target speed. At that point, sensors within Beagle 2 would deploy parachutes to further slow the lander’s descent. Then, at about a mile above the surface, large gas bags would inflate to cushion the landing as Beagle 2 bounced along the red planet’s surface. After Beagle 2 finally came to rest, the gas bags were to deflate, allowing the top of the lander to open, thereby exposing four solar array disks and a UHF antenna. The latter was programmed to send a signal (and possibly an image of the Martian surface) back to Earth.

Beagle 2 was scheduled to land at 2:54 p.m on Christmas Day and make its initial transmission about 5:30 UT. Another transmission  was to occur the next (local) morning to confirm that Beagle 2 survived the landing and the first night on Mars. But no signal was ever received and, a month later, the European Space Agency declared the Beagle 2 lost. However, it is nevertheless possible that Hirst’s spot painting survived and resides today on the Martian surface.

was to occur the next (local) morning to confirm that Beagle 2 survived the landing and the first night on Mars. But no signal was ever received and, a month later, the European Space Agency declared the Beagle 2 lost. However, it is nevertheless possible that Hirst’s spot painting survived and resides today on the Martian surface.

According to the ESA’s Director of Science, Professor David Southwood, it is unlikely that the lander burned up on descent or glanced off the Martian atmosphere and into deep space. In Southwood’s opinion, two other possibilities are more likely. The first is that the parachutes and gas bags did not work (for a variety of reasons) to adequately slow the lander, causing Beagle 2 to crash into the Martian surface and break apart.  Under this scenario, Hirst’s 3 x 3 inch aluminum plate spot painting could be sitting intact in a debris field scattered over several miles of Martian soil. Another, equally plausible, possibility is that Beagle 2 landed intact, but got entangled in the parachutes and airbags thereby preventing the top from opening. In this case, Hirst’s painting would definitely represent the first art to land on Mars.

Under this scenario, Hirst’s 3 x 3 inch aluminum plate spot painting could be sitting intact in a debris field scattered over several miles of Martian soil. Another, equally plausible, possibility is that Beagle 2 landed intact, but got entangled in the parachutes and airbags thereby preventing the top from opening. In this case, Hirst’s painting would definitely represent the first art to land on Mars.

Even if Hirst’s spot painting survives, it would have held the distinction of being the only art on Mars for just a few short days. That’s because on January 3, 2004, NASA successfully landed its  own rover in Mars’ Gusev Crater. Named Spirit, the rover contained artwork created by London-based Australian artist Stephen Little called Monochrome (for Mars). The artwork is contained in a DVD that includes the names of nearly 4 million enthusiasts who responded to NASA’s invitation to send their names to Mars. Little then engrafted red text reading “Monochrome (for Mars)” on the DVD. “I could have sent a physical object, such as a painting,” said Little at the time, “but it

own rover in Mars’ Gusev Crater. Named Spirit, the rover contained artwork created by London-based Australian artist Stephen Little called Monochrome (for Mars). The artwork is contained in a DVD that includes the names of nearly 4 million enthusiasts who responded to NASA’s invitation to send their names to Mars. Little then engrafted red text reading “Monochrome (for Mars)” on the DVD. “I could have sent a physical object, such as a painting,” said Little at the time, “but it  had to be placed on a DVD, so I was limited by the space I had on it as well.” (Designed to last for three months, Spirit roved for more than six years. The rover sent its last message in March of 2010, and after nearly a year of trying to reestablish communications with the Spirit Mars rover, NASA finally decided to suspend efforts in 2011.)

had to be placed on a DVD, so I was limited by the space I had on it as well.” (Designed to last for three months, Spirit roved for more than six years. The rover sent its last message in March of 2010, and after nearly a year of trying to reestablish communications with the Spirit Mars rover, NASA finally decided to suspend efforts in 2011.)

Of course, to recognize either Hirst or Little as the fist artists on Mars requires an expanded view of  what art is. Some might contend that colors and pigments chosen and arranged to calibrate cameras and sensors should not qualify as real art, and that Little’s lettering is just labelling and not actual art. Or at least not art in the sense of the drawings that Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Forrest Myers included in the Moon Museum. Each of their contributions made a

what art is. Some might contend that colors and pigments chosen and arranged to calibrate cameras and sensors should not qualify as real art, and that Little’s lettering is just labelling and not actual art. Or at least not art in the sense of the drawings that Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Forrest Myers included in the Moon Museum. Each of their contributions made a  statement about the history of art or the state of their own body of work. But if Yoko Ono and her colleagues have taught us anything since the 1960s about conceptual art, if Ben Patterson and his Fluxus contemporaries imparted any wisdom about happenings and performance art, then Hirst’s spot painting and Little’s Monochrome (for Mars) must be accepted as true works of art, and, therefore, Little and possibly Hirst must be recognized as the first and only artists with work represented on the red planet.

statement about the history of art or the state of their own body of work. But if Yoko Ono and her colleagues have taught us anything since the 1960s about conceptual art, if Ben Patterson and his Fluxus contemporaries imparted any wisdom about happenings and performance art, then Hirst’s spot painting and Little’s Monochrome (for Mars) must be accepted as true works of art, and, therefore, Little and possibly Hirst must be recognized as the first and only artists with work represented on the red planet.

Be that as it may, don’t miss your opportunity to see the very first space art. The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com

_______________________________________________

‘Moon Museum’ is not the only art on the moon (09-03-14)

The Moon Museum is not the only art on the moon. Less than two years after Intrepid landed in the Ocean of Storms, Apollo 15 Commander David Scott placed a 3½-inch-tall aluminum sculpture in a crater near his parked lunar rover in moon’s Hadley-Apennine region, between a meandering gulley and a range of steep mountains. Cast by Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, Fallen Astronaut pays tribute to all the astronauts and cosmonauts who lost their lives during the space race between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

The Moon Museum is not the only art on the moon. Less than two years after Intrepid landed in the Ocean of Storms, Apollo 15 Commander David Scott placed a 3½-inch-tall aluminum sculpture in a crater near his parked lunar rover in moon’s Hadley-Apennine region, between a meandering gulley and a range of steep mountains. Cast by Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, Fallen Astronaut pays tribute to all the astronauts and cosmonauts who lost their lives during the space race between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

In “The Sculpture on the Moon: Scandals and conflicts obscured one of the most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age,” American Science’s Acting Editor Corey S. Powell and Emmy-nominated filmmaker Laurie Gwen Shapiro write that Van Hoeydonck flew to Cape Kennedy to pitch the idea to NASA of placing sculpture on the moon at the urging of Louise Tolliver Deutschman, the director of the New York gallery that represented von Hoeydonck and his work. Once there, however, the sculptor ran into the same bureaucratic wall that prompted exasperated New York artist Frosty

In “The Sculpture on the Moon: Scandals and conflicts obscured one of the most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age,” American Science’s Acting Editor Corey S. Powell and Emmy-nominated filmmaker Laurie Gwen Shapiro write that Van Hoeydonck flew to Cape Kennedy to pitch the idea to NASA of placing sculpture on the moon at the urging of Louise Tolliver Deutschman, the director of the New York gallery that represented von Hoeydonck and his work. Once there, however, the sculptor ran into the same bureaucratic wall that prompted exasperated New York artist Frosty  Myers and Bell Labs scientist Fred Waldhauer to induce a Gruman Aircraft technician to secretly slip the Moon Museum ceramic wafer onto the Apollo 12 lunar lander without NASA’s knowledge or permission. In Hoeydonck’s case, he met a guy who arranged for him to have a casual dinner at a Cocoa Beach restaurant with the crew of Apollo 15.

Myers and Bell Labs scientist Fred Waldhauer to induce a Gruman Aircraft technician to secretly slip the Moon Museum ceramic wafer onto the Apollo 12 lunar lander without NASA’s knowledge or permission. In Hoeydonck’s case, he met a guy who arranged for him to have a casual dinner at a Cocoa Beach restaurant with the crew of Apollo 15.

Van Hoeydonck and Commander Scott hit it off from the outset. They discovered that they shared obsessions with archaeology and Mayan mythology. By night’s end, the crewmembers toasted the  star struck sculptor and promised to “get him a sculpture on the moon.” But the Apollo 15 crew had very definite views of what they wanted that sculpture to be. “We came up with the idea of recognizing the guys who’d died in the pursuit of space,” Scott told Powell and Shapiro for their December 16, 2013 piece. “We also wanted to recognize our Soviet colleagues as well,” a remarkable sentiment at the height of the space race.

star struck sculptor and promised to “get him a sculpture on the moon.” But the Apollo 15 crew had very definite views of what they wanted that sculpture to be. “We came up with the idea of recognizing the guys who’d died in the pursuit of space,” Scott told Powell and Shapiro for their December 16, 2013 piece. “We also wanted to recognize our Soviet colleagues as well,” a remarkable sentiment at the height of the space race.

That was not the only restriction Scott and his crew placed on the sculptor. Fallen Astronaut had to be small, unisex, raceless and able to withstand extreme temperature swings, where the highs during the day could reach 250 degrees Farenheit and lows at night could plummet to -250 F as well. Hoeydonck complied, fabricating a lightweight 3½ inch aluminum abstract figurine that Scott secreted aboard Apollo 15. And during his last lunar excursion, he found a home for Fallen Astronaut and an associated plaque as well.

That was not the only restriction Scott and his crew placed on the sculptor. Fallen Astronaut had to be small, unisex, raceless and able to withstand extreme temperature swings, where the highs during the day could reach 250 degrees Farenheit and lows at night could plummet to -250 F as well. Hoeydonck complied, fabricating a lightweight 3½ inch aluminum abstract figurine that Scott secreted aboard Apollo 15. And during his last lunar excursion, he found a home for Fallen Astronaut and an associated plaque as well.

“Irwin distracted Mission Control in Houston with inane chatter while Scott took a few bounding steps north from the lunar rover  and made Fallen Astronaut a citizen of the moon,” Powell and Shapiro report. “He pulled Fallen Astronaut from his oversize pocket, placed it directly on the moon dust, and nestled the memorial plaque next to it. A spiritual man who keeps his faith private, Scott treated the dedication of Fallen Astronaut as a wordless funeral service.”

and made Fallen Astronaut a citizen of the moon,” Powell and Shapiro report. “He pulled Fallen Astronaut from his oversize pocket, placed it directly on the moon dust, and nestled the memorial plaque next to it. A spiritual man who keeps his faith private, Scott treated the dedication of Fallen Astronaut as a wordless funeral service.”

Scott mentioned Fallen Astronaut just once after returning to Earh – in the post-mission press conference. And he failed to name van  Hoeydonck as the sculptor’s creator. “Nor did the official NASA press release that followed. Scott preferred to keep it that way—treating Fallen Astronaut as an anonymous memorial.” Von Hoeydonck was upset that he couldn’t mention, never lone take credit, for the achievement of placing a work of art on the moon’s surface. He was beyond dismayed that Scott had named his sculpture Fallen Astronaut rather than Gateway to the Stars, the name van Hoeydonck had intended and preferred. But after the Smithsonian Institute asked the Apollo 15 crew to have their “workman” cast a replica for the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, van Hoeydonck decided to go on CBS News with Walter Cronkite and announce to the world that he was the artist whose sculpture now looked down on the Earth from the surface of the moon.

Hoeydonck as the sculptor’s creator. “Nor did the official NASA press release that followed. Scott preferred to keep it that way—treating Fallen Astronaut as an anonymous memorial.” Von Hoeydonck was upset that he couldn’t mention, never lone take credit, for the achievement of placing a work of art on the moon’s surface. He was beyond dismayed that Scott had named his sculpture Fallen Astronaut rather than Gateway to the Stars, the name van Hoeydonck had intended and preferred. But after the Smithsonian Institute asked the Apollo 15 crew to have their “workman” cast a replica for the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, van Hoeydonck decided to go on CBS News with Walter Cronkite and announce to the world that he was the artist whose sculpture now looked down on the Earth from the surface of the moon.

“In the VIP area, there’s Jordan’s King Hussein and the two Nixon girls, Vice President Agnew, the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and the Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, the only artist with work on the moon,” began Cronkite, unaware of the Moon Museum and the fact that pop art and modernist icons Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John

“In the VIP area, there’s Jordan’s King Hussein and the two Nixon girls, Vice President Agnew, the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and the Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, the only artist with work on the moon,” began Cronkite, unaware of the Moon Museum and the fact that pop art and modernist icons Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John  Chamberlain, David Novros and Frosty Myers also had works of art on the moon. “Van Hoeydonck, clutching a Fallen Astronaut replica and sporting a white jacket and tie, explained his motivation in creating the sculpture,” recount Powell and Shapiro. “’I thought of the future of man, that the only possible future of man was in the stars.’ He started to describe Fallen Astronaut as the ‘smallest memorial on Earth.’ Cronkite cut him off: ‘—not on Earth, though. Smallest memorial in the universe. And there it is. That’s the way they left it.’”

Chamberlain, David Novros and Frosty Myers also had works of art on the moon. “Van Hoeydonck, clutching a Fallen Astronaut replica and sporting a white jacket and tie, explained his motivation in creating the sculpture,” recount Powell and Shapiro. “’I thought of the future of man, that the only possible future of man was in the stars.’ He started to describe Fallen Astronaut as the ‘smallest memorial on Earth.’ Cronkite cut him off: ‘—not on Earth, though. Smallest memorial in the universe. And there it is. That’s the way they left it.’”

Two weeks after the Cronkite interview, van Hoeydonck told The New Yorker that “amid all the debris of technology left in space, it is the only sign of man’s arts,” expressing a sentiment voiced two years earlier by Frosty Myers, who wanted to leave something more inspiring on the moon’s surface than space detritus.

Two weeks after the Cronkite interview, van Hoeydonck told The New Yorker that “amid all the debris of technology left in space, it is the only sign of man’s arts,” expressing a sentiment voiced two years earlier by Frosty Myers, who wanted to leave something more inspiring on the moon’s surface than space detritus.

Van Hoeydonck thought that the news would make him bigger than Picasso. To his chagrin, people hated the idea that an art “outsider” represented by a second tier gallery had possessed the temerity to place the first and only sculpture on the surface of the moon. Interestingly, one of van Hoeydonck’s most vociferous detractors was New York Times art critic Grace Glueck, who broke the story about the Moon Museum within days of the return of Apollo 12. “Writing in the April 22, 1972, edition of the New York Times, influential art critic Grace Glueck sniffed that the moon sculpture ‘resembles nothing so much as a swollen tuning fork,’” Powell and Shapiro report. Inexplicably, she apparently made no mention of the fact that a group of six prominent New York artists had beaten van Hoeydonck to the moon.

Van Hoeydonck thought that the news would make him bigger than Picasso. To his chagrin, people hated the idea that an art “outsider” represented by a second tier gallery had possessed the temerity to place the first and only sculpture on the surface of the moon. Interestingly, one of van Hoeydonck’s most vociferous detractors was New York Times art critic Grace Glueck, who broke the story about the Moon Museum within days of the return of Apollo 12. “Writing in the April 22, 1972, edition of the New York Times, influential art critic Grace Glueck sniffed that the moon sculpture ‘resembles nothing so much as a swollen tuning fork,’” Powell and Shapiro report. Inexplicably, she apparently made no mention of the fact that a group of six prominent New York artists had beaten van Hoeydonck to the moon.

The rift between van Hoeydonck worsened over the years, as the Powell and Shapiro article describes in delicious detail, with accusations from numerous sources denigrating van Hoeydonck for profiteering and commercial exploitation of the nation’s flights to the moon. Using van Hoeydonck’s experiences as a benchmark, Myers and his Moon Museum colleagues were wise to keep their involvement quiet in the decades that followed the Apollo 12 mission and refrain from publicizing or commercializing the art they’d placed on the moon.

The rift between van Hoeydonck worsened over the years, as the Powell and Shapiro article describes in delicious detail, with accusations from numerous sources denigrating van Hoeydonck for profiteering and commercial exploitation of the nation’s flights to the moon. Using van Hoeydonck’s experiences as a benchmark, Myers and his Moon Museum colleagues were wise to keep their involvement quiet in the decades that followed the Apollo 12 mission and refrain from publicizing or commercializing the art they’d placed on the moon.

For all their copious research, detailed analysis and lengthy reporting about Paul van Hoeydonck and the Fallen Astronaut sculpture, it is simultaneously curious, amusing and disturbing that Powell and Shapiro either did not know of the Moon Museum at the time they published their piece last December or chose, for whatever reasons, not to mention it. But you know that Rauschenberg, Warhol, Oldenburg, Chamberlain, Novros and Myers were the first artists to have work on the moon and that the Moon Museum remains the first and only museum to grace the lunar surface. The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com.

For all their copious research, detailed analysis and lengthy reporting about Paul van Hoeydonck and the Fallen Astronaut sculpture, it is simultaneously curious, amusing and disturbing that Powell and Shapiro either did not know of the Moon Museum at the time they published their piece last December or chose, for whatever reasons, not to mention it. But you know that Rauschenberg, Warhol, Oldenburg, Chamberlain, Novros and Myers were the first artists to have work on the moon and that the Moon Museum remains the first and only museum to grace the lunar surface. The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com.

_____________________________________________________________________

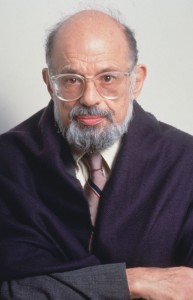

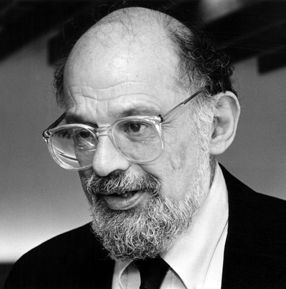

Unopened letter resulted in poet Allen Ginsberg missing flight to the moon (09-01-14)

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission is on view now through September 27 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The museum consists of a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. Somewhere between 16 and 40 chips were printed in the limited, single-run edition. One of the chips has resided on the moon since November 19, 1969, making the Moon Museum 6 the only artists in the world to have work on the lunar surface.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission is on view now through September 27 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The museum consists of a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. Somewhere between 16 and 40 chips were printed in the limited, single-run edition. One of the chips has resided on the moon since November 19, 1969, making the Moon Museum 6 the only artists in the world to have work on the lunar surface.

Myers was the one who conceived and orchestrated the project,  choosing the artists to include on the lunar-bound ceramic platform. But one of the artists that Myers invited missed the flight.

choosing the artists to include on the lunar-bound ceramic platform. But one of the artists that Myers invited missed the flight.

“I sent a letter to Allen Ginsberg,” relates Myers. But it sat unopened long after the other artists’ contributions had made their way to the moon. “As it turned out, Ginsberg sent [a] poem to me just a year or so too late [laughing]. Apparently, it took him that long to get around to answering his mail.”

Ginsberg titled the poem “Neil’s Ashes.” But it didn’t have anything to do with Neil Armstrong. Instead, it referred to Ginsberg’s lover, Neal Cassady. “I think Neil [sic] was alive at the time, but it was a beautiful poem that Allen had written on the backside of a piece of cardboard about the inevitable death of his lover,” Myers adds.

Ginsberg is best remembered as the radical poet who became a leading figure in the Flower Power movement, lecturing in American universities against the Vietnam war and chanting his mesmerizing Hare Krishna Mahamantra. ((This author had the good fortune to attend a reading he gave during an outdoor rally on the campus of the University of Florida in 1972.) His first important relationship was with Neal Cassady, who was a major figure of the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the psychedelic and counterculture movements of the 1960s. Ginsberg

Ginsberg is best remembered as the radical poet who became a leading figure in the Flower Power movement, lecturing in American universities against the Vietnam war and chanting his mesmerizing Hare Krishna Mahamantra. ((This author had the good fortune to attend a reading he gave during an outdoor rally on the campus of the University of Florida in 1972.) His first important relationship was with Neal Cassady, who was a major figure of the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the psychedelic and counterculture movements of the 1960s. Ginsberg  and Cassady met at Columbia University in 1947 and although the bisexual Cassady had a string of wives (LuAnne Cassady, Carolyn Robinson and Diane Hansen), he and Ginsberg maintained a sexual relationship that lasted, on and off, for nearly two decades.

and Cassady met at Columbia University in 1947 and although the bisexual Cassady had a string of wives (LuAnne Cassady, Carolyn Robinson and Diane Hansen), he and Ginsberg maintained a sexual relationship that lasted, on and off, for nearly two decades.

Cassady actually died some 18 months before the Apollo 12 mission, four days short of his 42nd  birthday. It is possible that one of the reasons Ginsberg did not open mail and respond in time to Myers’ invitation to include a poem in the Moon Museum was that he was still mourning his friend and lover’s death. But even though his homage does not grace the moon’s surface, Neal Cassady inspired much more during his brief life than Ginsberg’s untimely Moon Museum ode.

birthday. It is possible that one of the reasons Ginsberg did not open mail and respond in time to Myers’ invitation to include a poem in the Moon Museum was that he was still mourning his friend and lover’s death. But even though his homage does not grace the moon’s surface, Neal Cassady inspired much more during his brief life than Ginsberg’s untimely Moon Museum ode.

Long-time friend and author Jack Kerouac used Cassady as the model for his On the Road  character Dean Moriarty and for “Cody Pomeray” in many of other novels. (Cassady’s friendship with Kerouac was portrayed in John Byrum’s film, Heart Beat, starring Nick Nolte as Cassady and John Heard as Kerouac.) Another friend and author, Ken Kesey, is reputed to have used Cassady as the inspiration for the main character in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Kesey also wrote a fictional account of Cassady’s death in a short story titled “The Day After Superman Died” (published in Kesey’s 1986 Demon Box collection), in which

character Dean Moriarty and for “Cody Pomeray” in many of other novels. (Cassady’s friendship with Kerouac was portrayed in John Byrum’s film, Heart Beat, starring Nick Nolte as Cassady and John Heard as Kerouac.) Another friend and author, Ken Kesey, is reputed to have used Cassady as the inspiration for the main character in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Kesey also wrote a fictional account of Cassady’s death in a short story titled “The Day After Superman Died” (published in Kesey’s 1986 Demon Box collection), in which  Cassady mumbles the number of railroad ties he had counted on the line (64,928) as he expires. In Hunter S. Thompson’s book, Hell’s Angels, Cassady is described as “the worldly inspiration for the protagonist of two recent novels,” drunkenly yelling at police at the famed Hells Angels parties at Ken Kesey’s residence in La Honda, California, an event also chronicled in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Cassady mumbles the number of railroad ties he had counted on the line (64,928) as he expires. In Hunter S. Thompson’s book, Hell’s Angels, Cassady is described as “the worldly inspiration for the protagonist of two recent novels,” drunkenly yelling at police at the famed Hells Angels parties at Ken Kesey’s residence in La Honda, California, an event also chronicled in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Cassady was also memorialized in music by a number of bands and composers. Having lived briefly with The Grateful Dead, Cassady is immortalized in “The Other One” section of their song “That’s It For The Other One” as the bus driver “Cowboy Neal.” Doobie Brothers guitarist and songwriter Patrick Simmons refers to Cassady in his song “Neal’s Fandango” as his incentive for taking to the road. Tom Waits composed and recorded a song named “Jack & Neal” (included in his 1977 Foreign Affairs album)

“The Other One” section of their song “That’s It For The Other One” as the bus driver “Cowboy Neal.” Doobie Brothers guitarist and songwriter Patrick Simmons refers to Cassady in his song “Neal’s Fandango” as his incentive for taking to the road. Tom Waits composed and recorded a song named “Jack & Neal” (included in his 1977 Foreign Affairs album)  about a trip to California with Neal Cassady driving in the company of Jack Kerouac. And just this year, British musician Morrissey featured a track titled “Neal Cassady Drops Dead” in his World Peace Is None of Your Business album.

about a trip to California with Neal Cassady driving in the company of Jack Kerouac. And just this year, British musician Morrissey featured a track titled “Neal Cassady Drops Dead” in his World Peace Is None of Your Business album.

Numerous films have based characters on, or made pop culture references to, Neal Cassady, including Who’ll Stop The Rain. Based on Robert  Stone’s novel, Dog Soldiers, the character of Ray Hicks (played by Nick Nolte) is based on Cassady, with whom Stone became acquainted through novelist Kesey, a classmate of Stone’s in graduate school at Stanford University. Hicks’ death scene on the railroad tracks at the film’s conclusion is patterned after Cassady’s death along a railroad track outside of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico in 1968.

Stone’s novel, Dog Soldiers, the character of Ray Hicks (played by Nick Nolte) is based on Cassady, with whom Stone became acquainted through novelist Kesey, a classmate of Stone’s in graduate school at Stanford University. Hicks’ death scene on the railroad tracks at the film’s conclusion is patterned after Cassady’s death along a railroad track outside of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico in 1968.

The Last Time I Committed Suicide (1997), with Thomas Jane as Cassady, is based on the “Joan Anderson letter” written by Cassady to Jack Kerouac in December 1950. A 2007 short film, Luz Del Mundo, deals with Cassady’s friendship and adventures with Jack Kerouac. Cassady is portrayed in the 2010 film, Howl, which chronicles the creation of Ginsberg’s avant-garde gay culture coming-out poem of the same name, and the obscenity trial surrounding its publication. The 2011 documentary Love Always, Carolyn – A film about Kerouac, Cassady and Me

The Last Time I Committed Suicide (1997), with Thomas Jane as Cassady, is based on the “Joan Anderson letter” written by Cassady to Jack Kerouac in December 1950. A 2007 short film, Luz Del Mundo, deals with Cassady’s friendship and adventures with Jack Kerouac. Cassady is portrayed in the 2010 film, Howl, which chronicles the creation of Ginsberg’s avant-garde gay culture coming-out poem of the same name, and the obscenity trial surrounding its publication. The 2011 documentary Love Always, Carolyn – A film about Kerouac, Cassady and Me  features archive footage as well as interviews with Cassady’s wife Carolyn and children, and Alex Gibney’s 2011 documentary, Magic Trip, uses footage shot by Kesey and the Merry Pranksters during their cross-country bus trip during which the hyperkinetic Cassady is frequently seen

features archive footage as well as interviews with Cassady’s wife Carolyn and children, and Alex Gibney’s 2011 documentary, Magic Trip, uses footage shot by Kesey and the Merry Pranksters during their cross-country bus trip during which the hyperkinetic Cassady is frequently seen  driving the bus, jabbering, and sitting next to a sign that boasts, “Neal gets things done.”

driving the bus, jabbering, and sitting next to a sign that boasts, “Neal gets things done.”

Ginsberg’s and Cassady’s inclusion on the Moon Museum would have undoubtedly added to the project’s allure, but all of us have left the mail unopened a time or two – although perhaps not for a year or more.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com.

__________________________________________________________

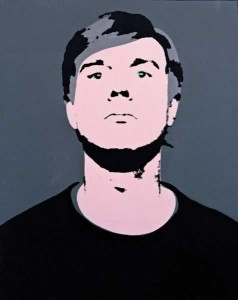

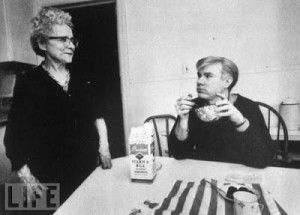

Pondering Andy Warhol’s ‘Moon Museum’ calligraphic spiggle (08-31-14)

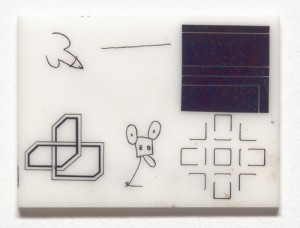

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission opened August 22 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. As the title of the exhibition indicates, the headliner of the show is the Moon Museum, a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros, Forrest “Frosty” Myers and Andy Warhol. A duplicate of the chip was surreptitiously placed on the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and unwittingly delivered to the moon by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission opened August 22 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. As the title of the exhibition indicates, the headliner of the show is the Moon Museum, a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros, Forrest “Frosty” Myers and Andy Warhol. A duplicate of the chip was surreptitiously placed on the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and unwittingly delivered to the moon by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F.  Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. It has resided in the Ocean of Storms ever since, holding the distinction of being the first and, to date, only art museum in outer space, never lone on the moon’s surface.

Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. It has resided in the Ocean of Storms ever since, holding the distinction of being the first and, to date, only art museum in outer space, never lone on the moon’s surface.

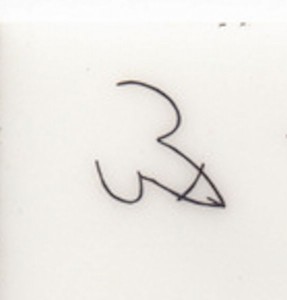

Myers was the one who conceived and orchestrated the project, choosing the artists to include on the lunar-bound ceramic platform. In 1969, Myers described Warhol’s contribution to New York Times reporter Grace Glueck as “a calligraphic spiggle made up of the initials of his signature.” Those were more genteel times, and some postulated the drawing was, a’ propos, a rocket ship. In 2009, Myers fessed up, bluntly characterizing the drawing as “Warhol’s now infamous ‘AW’ penis sketch.”

But Myers is quick to add that it would be easy to dismiss Warhol’s drawing “if you don’t know [his] work.” But ascribing meaning to the calligraphic rendering is as multi-dimensional and layered as Warhol’s overall oeuvre of work, and what Warhol actually meant to convey will remain a matter of conjecture – which is appropriate, given that throughout the course of his career as a fine artist, Warhol refused to explain his work, famously declaring that all you need to know about him and his work is already there “on the surface.”

But Myers is quick to add that it would be easy to dismiss Warhol’s drawing “if you don’t know [his] work.” But ascribing meaning to the calligraphic rendering is as multi-dimensional and layered as Warhol’s overall oeuvre of work, and what Warhol actually meant to convey will remain a matter of conjecture – which is appropriate, given that throughout the course of his career as a fine artist, Warhol refused to explain his work, famously declaring that all you need to know about him and his work is already there “on the surface.”

Father of Pop Art Movement

On one level, the use of phallic imagery could simply signify that Warhol saw himself as the father of the Pop Art movement. Indeed, he was referred to as the “Pope of Pop Art.” However, Warhol assiduously avoided drawing attention to the fact that he was a devout Byzantine Catholic who at times attended services on a daily basis. “Father of Pop Art” would have been an appellation with which he was far more comfortable, and in this regard, Warhol clearly pioneered the Pop movement, not only in art, but in sculpture, photography, film, literature and even

On one level, the use of phallic imagery could simply signify that Warhol saw himself as the father of the Pop Art movement. Indeed, he was referred to as the “Pope of Pop Art.” However, Warhol assiduously avoided drawing attention to the fact that he was a devout Byzantine Catholic who at times attended services on a daily basis. “Father of Pop Art” would have been an appellation with which he was far more comfortable, and in this regard, Warhol clearly pioneered the Pop movement, not only in art, but in sculpture, photography, film, literature and even  music (where he produced the band Velvet Underground). He influenced a host of celebrities, endorsed products, appeared in commercials and made frequent guest appearances on television shows and in films. He appeared in everything from the Love Boat and Saturday Night Live to the Richard Pryor movie Dynamite Chicken.

music (where he produced the band Velvet Underground). He influenced a host of celebrities, endorsed products, appeared in commercials and made frequent guest appearances on television shows and in films. He appeared in everything from the Love Boat and Saturday Night Live to the Richard Pryor movie Dynamite Chicken.

From the time of MoMA’s Symposium on Pop Art in December 1962, it became increasingly clear that there had been a profound change in the culture of the art world and that Warhol was at the center of that shift. Warhol was the one whose work made the cleanest and most radical break with previous art — a rupture that demonstrates the single-mindedness of his conception and the way in which his themes and motifs resonated with the spirit of America’s postwar consumer society. So Warhol can be forgiven if he meant his Moon Museum iconography as a recognition of his seminal role in creating and promoting pop culture.

Frivolity as Antidote to Stodginess of Abstract Expressionists

Was Warhol merely being cavalier or frivolous in providing a sketch that utilizes his initials to evoke a penis-shaped rocket (or vice versa) for the Moon Museum project? Perhaps, but Warhol used frivolity as counterpoint to the lofty and serious discourse embraced by the Abstract Expressionists of his day. To their horror and the disgust of most of the art critics of the 1960s (who often derided him as a hoax or “put-on”), Warhol eschewed conventional artistic motifs in favor of the ubiquitous imagery found in popular culture and the mass media. Thus, celebrity photos from magazines and tabloids, advertising graphics for mass consumer products, and underground comics all became “grist for Warhol’s roving, omnivorous imagination, which transmuted these images into art without altering much of its essential character as visual kitsch,” as one Warhol biographer notes.

Was Warhol merely being cavalier or frivolous in providing a sketch that utilizes his initials to evoke a penis-shaped rocket (or vice versa) for the Moon Museum project? Perhaps, but Warhol used frivolity as counterpoint to the lofty and serious discourse embraced by the Abstract Expressionists of his day. To their horror and the disgust of most of the art critics of the 1960s (who often derided him as a hoax or “put-on”), Warhol eschewed conventional artistic motifs in favor of the ubiquitous imagery found in popular culture and the mass media. Thus, celebrity photos from magazines and tabloids, advertising graphics for mass consumer products, and underground comics all became “grist for Warhol’s roving, omnivorous imagination, which transmuted these images into art without altering much of its essential character as visual kitsch,” as one Warhol biographer notes.

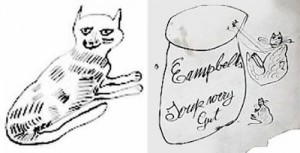

Warhol as Progenitor of Mass Produced Artworks

It is also possible that Warhol employed the penis imagery philosophically. Through the use of silk screens and a bevy of assistants, Warhol mass produced artwork that unabashedly incorporated mass-produced products such as Brillo, Campbell’s Soup Cans and Coca Cola, as well as Hollywood-produced stars like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. Taking pains to minimize the role of his own hand in the production of his art, he would conceive an idea and then oversee or delegate its execution. As he refined this approach, his Factory in Manhattan evolved from an atelier into an office, with Warhol becoming a brand and the essence of the Pop Art movement.

It is also possible that Warhol employed the penis imagery philosophically. Through the use of silk screens and a bevy of assistants, Warhol mass produced artwork that unabashedly incorporated mass-produced products such as Brillo, Campbell’s Soup Cans and Coca Cola, as well as Hollywood-produced stars like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. Taking pains to minimize the role of his own hand in the production of his art, he would conceive an idea and then oversee or delegate its execution. As he refined this approach, his Factory in Manhattan evolved from an atelier into an office, with Warhol becoming a brand and the essence of the Pop Art movement.

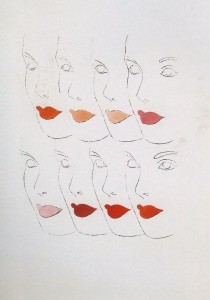

Blotted Line Technique

Prior to launching his career in fine art in the 1960s, Warhol worked in advertising and marketing, where he developed a special type of line drawing known as the blotted line technique. Warhol first experimented with blotted line while still a college student at Carnegie Institute of Technology and continued to refine the technique in his commercial work in New York City throughout the 1950s. Blotted line enabled him to create a variety of illustrations along a similar theme. Presenting multiple drawings to clients increased the likelihood that his work would be chosen for the final advertisement.

Prior to launching his career in fine art in the 1960s, Warhol worked in advertising and marketing, where he developed a special type of line drawing known as the blotted line technique. Warhol first experimented with blotted line while still a college student at Carnegie Institute of Technology and continued to refine the technique in his commercial work in New York City throughout the 1950s. Blotted line enabled him to create a variety of illustrations along a similar theme. Presenting multiple drawings to clients increased the likelihood that his work would be chosen for the final advertisement.

Blotted line combines drawing with very basic printmaking. Warhol  began by making a line drawing on a piece of non-absorbent paper, such as tracing paper. Next, he hinged this piece of paper to a second sheet of more absorbent paper by taping their edges together on one side. With an old fountain pen, Warhol inked over a small section of the drawn lines then transferred the ink onto the second sheet by folding along the hinge and lightly

began by making a line drawing on a piece of non-absorbent paper, such as tracing paper. Next, he hinged this piece of paper to a second sheet of more absorbent paper by taping their edges together on one side. With an old fountain pen, Warhol inked over a small section of the drawn lines then transferred the ink onto the second sheet by folding along the hinge and lightly  pressing or “blotting” the two papers together. Larger drawings were made in sections. Completing a large blotted line drawing could take quite a bit of time and multiple pressings. The process resulted in the dotted, broken, and delicate lines that are characteristic of Warhol’s illustrations. Warhol often colored his blotted line drawings with watercolor dyes or applied gold leaf.

pressing or “blotting” the two papers together. Larger drawings were made in sections. Completing a large blotted line drawing could take quite a bit of time and multiple pressings. The process resulted in the dotted, broken, and delicate lines that are characteristic of Warhol’s illustrations. Warhol often colored his blotted line drawings with watercolor dyes or applied gold leaf.

Warhol credits his mother with inspiring the technique. In fact, Warhol collaborated with his mother, Julia Warhola, throughout his career, and ostensibly appropriated her calligraphic drawing of a Campbell’s Soup can years later in his own iconic Pop Art painting. Warhol especially admired Julia’s distinctive handwriting, and his so-called “calligraphic spiggle” may have been, on some plane, a homage to his mom, who moved to New York City when Andy was a young art director at Doubleday and even shared an apartment with him.

Erotic Photography and Drawings

No analysis of Warhol’s Moon Museum drawing would be complete without at least acknowledging Warhol’s tradition of producing throughout much of his career erotic photography and drawings of male nudes. His portraits of Liza Minnelli, Judy Garland and Elizabeth Taylor as well as films like Blow Job, My Hustler and Lonesome Cowboys draw from gay underground culture and openly explore the complexity of sexuality and desire. The

No analysis of Warhol’s Moon Museum drawing would be complete without at least acknowledging Warhol’s tradition of producing throughout much of his career erotic photography and drawings of male nudes. His portraits of Liza Minnelli, Judy Garland and Elizabeth Taylor as well as films like Blow Job, My Hustler and Lonesome Cowboys draw from gay underground culture and openly explore the complexity of sexuality and desire. The  first works that Warhol submitted to a gallery were homoerotic drawings of male nudes. They were rejected for being too openly gay, which may have prompted Warhol to wryly place a rendering of a penis on the moon, where it could look down on Manhattan and all the provincial, parochial galleries, gallerists and dealers who were so behind the times.

first works that Warhol submitted to a gallery were homoerotic drawings of male nudes. They were rejected for being too openly gay, which may have prompted Warhol to wryly place a rendering of a penis on the moon, where it could look down on Manhattan and all the provincial, parochial galleries, gallerists and dealers who were so behind the times.

It is also possible that his penis drawing was  intended as a rejoinder to Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who found Warhol “too swish” for their liking. “There was nothing I could say to that. It was all too true,” Warhol wrote at the time. “So I decided I just wasn’t going to care because those were all the things that I didn’t want to change anyway, that I didn’t think I ‘should’ want to change… Other people could change their attitudes, but not me.”

intended as a rejoinder to Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who found Warhol “too swish” for their liking. “There was nothing I could say to that. It was all too true,” Warhol wrote at the time. “So I decided I just wasn’t going to care because those were all the things that I didn’t want to change anyway, that I didn’t think I ‘should’ want to change… Other people could change their attitudes, but not me.”

If Forrest Myers knows why Warhol chose to  include a penis-shaped rocket made out of his initials on the Moon Museum, he hasn’t said … at least not publicly. But then again, if Warhol wouldn’t have disclosed his true meaning, why should Myers or anyone else? You decide the significance to accord to Warhol’s spiggle. For that matter, you decide what you would have included had Myers asked you to contribute something for his Moon Museum project.

include a penis-shaped rocket made out of his initials on the Moon Museum, he hasn’t said … at least not publicly. But then again, if Warhol wouldn’t have disclosed his true meaning, why should Myers or anyone else? You decide the significance to accord to Warhol’s spiggle. For that matter, you decide what you would have included had Myers asked you to contribute something for his Moon Museum project.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com

________________________________________________________________________________________

Forrest Myers’ ‘Moon Museum’ drawing based on sculpture that befuddled MIT profs and students (08-30-14)

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission opened August 22 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. As the title of the exhibition indicates, the headliner of the show is the Moon Museum, a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty”

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission opened August 22 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. As the title of the exhibition indicates, the headliner of the show is the Moon Museum, a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, David Novros and Forrest “Frosty”  Myers. A duplicate of the chip was surreptitiously placed on the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and unwittingly delivered to the moon by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F. Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. It has resided in the Ocean of Storms ever since, holding the distinction of being the first and, to date, only art museum in outer space, never lone on the moon’s surface.

Myers. A duplicate of the chip was surreptitiously placed on the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and unwittingly delivered to the moon by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F. Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. It has resided in the Ocean of Storms ever since, holding the distinction of being the first and, to date, only art museum in outer space, never lone on the moon’s surface.

It was Myers who orchestrated the Moon Museum project, and he’s the one who chose the other five artists who would enjoy the distinction of being the first artists to send their work into outer space. To find out what Bob Rauschenberg intended with the line drawing that he provided for the project, pick up the current edition of Art Districts magazine. To decode the drawings submitted for the Moon Museum by Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain and David Novros, please scroll down on this page in Art Southwest Florida. And to learn what Myers himself sought to convey, visit the gallery and refer to the

It was Myers who orchestrated the Moon Museum project, and he’s the one who chose the other five artists who would enjoy the distinction of being the first artists to send their work into outer space. To find out what Bob Rauschenberg intended with the line drawing that he provided for the project, pick up the current edition of Art Districts magazine. To decode the drawings submitted for the Moon Museum by Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain and David Novros, please scroll down on this page in Art Southwest Florida. And to learn what Myers himself sought to convey, visit the gallery and refer to the  exhibition catalogue provided for the show by curator and Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger. Inside, Dellinger reprints an excerpt of a conversation he had with Myers on March 28, 2009 in advance of his on-going mission to bring the Moon Museum to light so as to expand and expound upon the legacy of Robert Rauschenberg and the other Moon Museum participants.

exhibition catalogue provided for the show by curator and Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger. Inside, Dellinger reprints an excerpt of a conversation he had with Myers on March 28, 2009 in advance of his on-going mission to bring the Moon Museum to light so as to expand and expound upon the legacy of Robert Rauschenberg and the other Moon Museum participants.

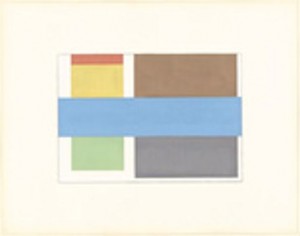

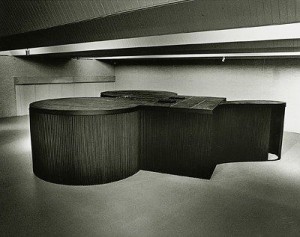

“[My contribution is] a drawing for (0r related to)  a sculpture …. I was involved with a collective or artists, including Mark DiSuvero, who started the Park Place Gallery [in the SoHo region in Manhattan],” Myers told Dellinger by way of introduction. “We exhibited together often in the mid-1960s, and were invited to participate in a group show at MIT during this period. I presented a large (perhaps seven feet high) metal sculpture in the exhibition. It was deceptively simple. At first glance, it appears to be aligned geometric forms, but upon closer inspection, you realize that the forms are interlocking and that they are derived from a continuous line,” resembling the lay-out of a Formula One racetrack that you might find at Monza, Hockenheim or Watkins Glen.

a sculpture …. I was involved with a collective or artists, including Mark DiSuvero, who started the Park Place Gallery [in the SoHo region in Manhattan],” Myers told Dellinger by way of introduction. “We exhibited together often in the mid-1960s, and were invited to participate in a group show at MIT during this period. I presented a large (perhaps seven feet high) metal sculpture in the exhibition. It was deceptively simple. At first glance, it appears to be aligned geometric forms, but upon closer inspection, you realize that the forms are interlocking and that they are derived from a continuous line,” resembling the lay-out of a Formula One racetrack that you might find at Monza, Hockenheim or Watkins Glen.

“When the work was being installed,” Myers continues, “I was approached by several students and then by their professors at MIT. Astonished by my sculpture, they confessed that my work was a precise physical manifestation of a computer rendering they had spent the entire semester plotting. They had been contemplating some

“When the work was being installed,” Myers continues, “I was approached by several students and then by their professors at MIT. Astonished by my sculpture, they confessed that my work was a precise physical manifestation of a computer rendering they had spent the entire semester plotting. They had been contemplating some  complicated mathematical problem by assigning coordinates to create a virtual object that was identical to the sculpture I had created for the exhibition.”

complicated mathematical problem by assigning coordinates to create a virtual object that was identical to the sculpture I had created for the exhibition.”

This was at a time when PCs, tablets, Photoshop, Paint Box and other illustration programs were yet to be conceived. “The MIT computer didn’t even have a mouse,” Myers noted. “They were using something that looked like a joy stick but,  much to my surprise, they were able to take my sculptural form and manipulate it in virtual space. With their primitive joy stick, you could rotate and spin my sculpture effortlessly – as if it were floating in a zero-gravity environment. They made the form weightless, and could stop motion with equal ease. The ‘computer drawing’ I included on the Moon Museum was, in fact, one of several screen-captures taken with a Polaroid camera.”

much to my surprise, they were able to take my sculptural form and manipulate it in virtual space. With their primitive joy stick, you could rotate and spin my sculpture effortlessly – as if it were floating in a zero-gravity environment. They made the form weightless, and could stop motion with equal ease. The ‘computer drawing’ I included on the Moon Museum was, in fact, one of several screen-captures taken with a Polaroid camera.”

Thus, Myers’ Moon Museum drawing was a tw0-dimensional representation of a sculptural form that was plotted in virtual space by the MIT team independently of Myers’ 3D sculpture.

Thus, Myers’ Moon Museum drawing was a tw0-dimensional representation of a sculptural form that was plotted in virtual space by the MIT team independently of Myers’ 3D sculpture.

“They had created this form through tedious computation, and were very curious to know how I had visualized mine,” Myers revealed, no doubt grinning widely as he recounted the story to Dellinger in his New York digs. “They kept asking me to reveal exactly how, as a sculptor, I had come to the same basic solution. Unfortunately, when I  explained that my inspiration came from some combination of alcohol, drugs and depression – verging on serious thoughts of suicide – they lost interest immediately. My MIT collaborators quickly realized I wasn’t the mathematical genius they assumed I must be!”

explained that my inspiration came from some combination of alcohol, drugs and depression – verging on serious thoughts of suicide – they lost interest immediately. My MIT collaborators quickly realized I wasn’t the mathematical genius they assumed I must be!”

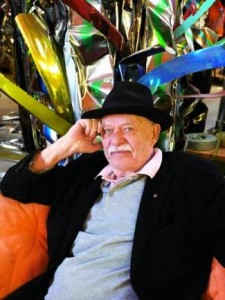

Self-deprecating to the last, Myers is remembered and regarded as one of the pioneers of the SoHo art district of the 1960s, a place where, in the words of writer Joelle Panisch, an artist could get “a 5,000 foot loft for three hundred dollars a month,” “genius roamed the streets like the dinosaur roamed the earth,” and “community grew out of necessity, bonds were formed,  inspirations shared and careers launched … fueled by creativity,” its product being change. And Myers was in the thick of it from the start. “There was just a lot of forces coming together,” Myers told Panisch in 2008. “There were several different disciplines going on at the same time–pop art, abstract expressionism, hard edge in both painting and sculpture, minimalism. These happened and at the same time they were overlapping each other. The discussions and the philosophies that were going around were just amazing for

inspirations shared and careers launched … fueled by creativity,” its product being change. And Myers was in the thick of it from the start. “There was just a lot of forces coming together,” Myers told Panisch in 2008. “There were several different disciplines going on at the same time–pop art, abstract expressionism, hard edge in both painting and sculpture, minimalism. These happened and at the same time they were overlapping each other. The discussions and the philosophies that were going around were just amazing for  artists. We didn’t have the kind of communication that we have today and the art magazines were pathetic. You’d go to a certain opening and your life was changed when you left. The art actually changed the way people saw things.” And among the artists with whom Myers rubbed shoulders in SoHo at the time were the other Moon Museum artists like Rauschenberg, Warhol, Chamberlain, Novros, and Oldenburg.

artists. We didn’t have the kind of communication that we have today and the art magazines were pathetic. You’d go to a certain opening and your life was changed when you left. The art actually changed the way people saw things.” And among the artists with whom Myers rubbed shoulders in SoHo at the time were the other Moon Museum artists like Rauschenberg, Warhol, Chamberlain, Novros, and Oldenburg.

Critical success came early. Myers was a founding member of the Park Place Gallery, which he believes was the first gallery in the neighborhood. He also designed Max’s Kansas City, a bar where artists working in different genres could meet and debate ideas. Myers’ Search Light Sculpture appeared in Tompkins Square Park during 1967, the same year he enjoyed a solo show at Paula Cooper. His boxy aluminum Fold Chair was shown at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan and in 1974 his monumental piece, The Wall, was unveiled on the side of 599 Broadway, at the corner of Broadway and Houston. After being threatened for a number of years, The Wall has recently been recognized as an historic site, hopefully securing the piece for the public’s enjoyment for generations to come.

Critical success came early. Myers was a founding member of the Park Place Gallery, which he believes was the first gallery in the neighborhood. He also designed Max’s Kansas City, a bar where artists working in different genres could meet and debate ideas. Myers’ Search Light Sculpture appeared in Tompkins Square Park during 1967, the same year he enjoyed a solo show at Paula Cooper. His boxy aluminum Fold Chair was shown at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan and in 1974 his monumental piece, The Wall, was unveiled on the side of 599 Broadway, at the corner of Broadway and Houston. After being threatened for a number of years, The Wall has recently been recognized as an historic site, hopefully securing the piece for the public’s enjoyment for generations to come.

Myers has remained active as an artist over the intervening decades, making new work in a variety of media and revisiting older works. He continues to exhibit his work in both solo and group shows around the country.

Myers has remained active as an artist over the intervening decades, making new work in a variety of media and revisiting older works. He continues to exhibit his work in both solo and group shows around the country.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Art Districts article delineates how Moon Museum exhibit sheds new insight on Bob Rauschenberg’s legacy (08-23-14)

The Moon Museum exhibition at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery prompts several important questions. One of them is, presented with the opportunity to make a statement about art in general and his own body of work in particular, what did Robert Rauschenberg intend to convey by the slightly ascending line he drew on the Moon Museum ceramic chip that was secreted to the lunar surface aboard the landing module, Intrepid? This author attempts to answer that question with the help of Bob Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger and Moon Museum quarterback Forrest “Frosty” Myers in an article titled “‘Moon Museum’ Exhibit Sheds New Insight on the Rauschenberg Legacy” that appears in the current (No. 31, August/September) issue of ArtDistricts magazine. Pick up you copy now. And to read more about the clandestine plot to land a museum on the moon and what the other Moon Museum 6 intended to impart with their drawings, please click here.

The Moon Museum exhibition at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery prompts several important questions. One of them is, presented with the opportunity to make a statement about art in general and his own body of work in particular, what did Robert Rauschenberg intend to convey by the slightly ascending line he drew on the Moon Museum ceramic chip that was secreted to the lunar surface aboard the landing module, Intrepid? This author attempts to answer that question with the help of Bob Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger and Moon Museum quarterback Forrest “Frosty” Myers in an article titled “‘Moon Museum’ Exhibit Sheds New Insight on the Rauschenberg Legacy” that appears in the current (No. 31, August/September) issue of ArtDistricts magazine. Pick up you copy now. And to read more about the clandestine plot to land a museum on the moon and what the other Moon Museum 6 intended to impart with their drawings, please click here.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Don’t get waylaid by ‘Moon Museum’ mystique, chip offers lessons about artists and nature of a museum (08-23-14)

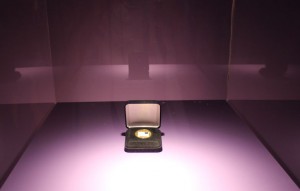

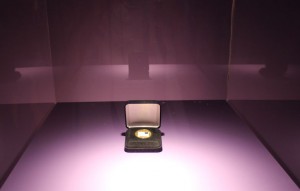

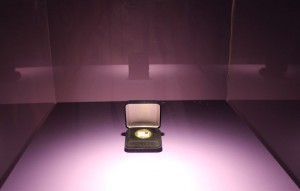

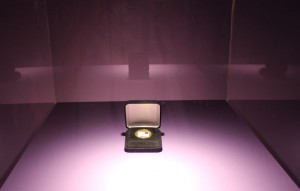

Last night, the Moon Museum opened at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The exhibit showcases a paper thin ceramic chip that contains truncated drawings by some of the 1960’s most iconic artists, Andy Warhol, Bob Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. A duplicate of the one on view in a lighted vitrine display inside the

Last night, the Moon Museum opened at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The exhibit showcases a paper thin ceramic chip that contains truncated drawings by some of the 1960’s most iconic artists, Andy Warhol, Bob Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, John Chamberlain and Forrest “Frosty” Myers. A duplicate of the one on view in a lighted vitrine display inside the  Rauschenberg Gallery was snuck onto the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and flown to the Ocean of Storms by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F. Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. without their knowledge. To this day, it is the only art on the moon’s surface and one of the few artworks to ever leave the earth’s atmosphere.

Rauschenberg Gallery was snuck onto the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander, Intrepid, and flown to the Ocean of Storms by astronauts Alan Bean, Richard F. Gordon and Charles Conrad, Jr. without their knowledge. To this day, it is the only art on the moon’s surface and one of the few artworks to ever leave the earth’s atmosphere.

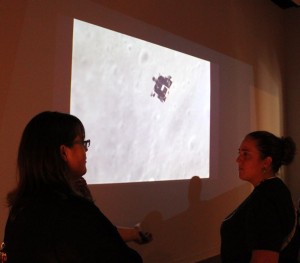

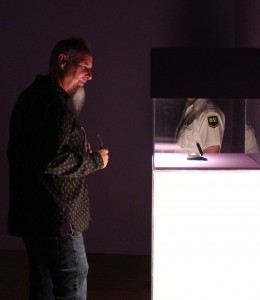

Perhaps it was the chip’s ridiculously miniscule size or the improbable set of circumstances that resulted in its delivery to the moon without NASA’s permission or knowledge, but most of the guests who attended the opening approached the glass case housing the duplicate with the bated-breath reverence of a Brit beholding the crown jewels or Indiana Jones laying widening self-satisfied eyes on the Holy Grail. New arrivals took scant notice of the video playing against the right wall of the Intrepid gliding toward its preordained

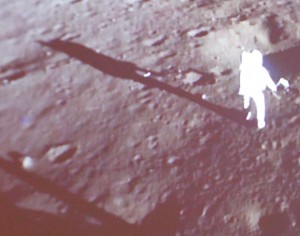

Perhaps it was the chip’s ridiculously miniscule size or the improbable set of circumstances that resulted in its delivery to the moon without NASA’s permission or knowledge, but most of the guests who attended the opening approached the glass case housing the duplicate with the bated-breath reverence of a Brit beholding the crown jewels or Indiana Jones laying widening self-satisfied eyes on the Holy Grail. New arrivals took scant notice of the video playing against the right wall of the Intrepid gliding toward its preordained  pocked landing site or Alan Bean bounding along the powdery crater beneath the lunar module’s metal feet. They didn’t pause to gander at the glass-encased photographs, kapton foil, NASA patches and other artifacts in the display extending down the opposing wall. There would be time enough for all that later on. Instead, each newcomer, in turn, made a beeline for the

pocked landing site or Alan Bean bounding along the powdery crater beneath the lunar module’s metal feet. They didn’t pause to gander at the glass-encased photographs, kapton foil, NASA patches and other artifacts in the display extending down the opposing wall. There would be time enough for all that later on. Instead, each newcomer, in turn, made a beeline for the  Moon Museum, bending and leaning in to peer piously at the tiny communion-style wafer laying on its gold bed inside a velvety jewelry box.

Moon Museum, bending and leaning in to peer piously at the tiny communion-style wafer laying on its gold bed inside a velvety jewelry box.

It took but a few intimate seconds for the Moon Museum to work its magic. It’s doubtful in that brief encounter that many viewers paused to really embrace the artworks rendered by the Moon Museum 6. It seemed sufficient for them to know that they were laying private eyes on an object that  few of the planet’s other 8 billion humans were even aware of, never lone seen. Like the artists, engineers and other scientists who hatched and executed the clandestine plot to land a museum on the moon, they were now part of the too, too delicious conspiracy.

few of the planet’s other 8 billion humans were even aware of, never lone seen. Like the artists, engineers and other scientists who hatched and executed the clandestine plot to land a museum on the moon, they were now part of the too, too delicious conspiracy.

Some may have fashioned themselves a future space explorer, happening upon a relic from a long-passed civilization. Others might have envisioned themselves a real life a modern-day Man from U.N.C.L.E. or edgy Ethan Hunt. Was Tincture gallery  owner Terry Tincher imagining himself as Jason Bourne or Austin Powers? Was Mound House/Mound Key archaeologist Theresa Schober conjuring her inner Evelyn Salt or Sydney Brestow?

owner Terry Tincher imagining himself as Jason Bourne or Austin Powers? Was Mound House/Mound Key archaeologist Theresa Schober conjuring her inner Evelyn Salt or Sydney Brestow?

Whatever drew them to the chip like iron to an electromagnet, and whatever they experienced while gazing raptly at the chip, this author certainly hopes that whether then, now or some day in the future, each Moon Museum viewer contemplate two important things. First, presented with the unparalleled and unrepeated opportunity to extend their legacy into outer space, what did the Moon Museum 6 intend to convey with the drawings they had their Bell Lab co-conspirators engraft  onto the lunar-bound wafer? And secondly, could it really be that a ceramic wafer no bigger than a thumbnail qualified as a real and true museum?

onto the lunar-bound wafer? And secondly, could it really be that a ceramic wafer no bigger than a thumbnail qualified as a real and true museum?

To learn what Bob Rauschenberg meant to convey with his upward inclining line, please pick up the current edition of Art Districts magazine (ed. 31, August/September 2014) and read “’Moon Museum’ Exhibit Sheds New Insight on the Rauschenberg Legacy” on pages 26-28. To discover the message behind Claes Oldenburg’s Geometric  Mouse, John Chamberlain’s grid drawing and David Novros’ movable mural architectural panel, please refer to the applicable article posted under “Moon Museum Exhibition” on Art Southwest Florida. And to discern Warhol’s and Myers’ intent, pick up a copy of the exhibition brochure and read the interview that Forrest Myers gave Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger in 2008. It’s tough stuff, but important reading if you really want to gain insight into the minds and legacies of six of the most

Mouse, John Chamberlain’s grid drawing and David Novros’ movable mural architectural panel, please refer to the applicable article posted under “Moon Museum Exhibition” on Art Southwest Florida. And to discern Warhol’s and Myers’ intent, pick up a copy of the exhibition brochure and read the interview that Forrest Myers gave Rauschenberg Gallery Director Jade Dellinger in 2008. It’s tough stuff, but important reading if you really want to gain insight into the minds and legacies of six of the most  important artists of the last 50 or 60 years.

important artists of the last 50 or 60 years.

But to fathom the depths of the second philosophical/philological conundrum, all you have to do is harken back to the lessons that Dellinger has tried to impart since assuming the reins of the Rauschenberg Gallery. A museum is so much more than a building in which art is displayed. As Dellinger and Sean Miller demonstrated via the John Erickson Museum of  Art (JEMA), a museum can fit into a location-variable box that gives the exhibiting artists the freedom to create unfettered by the shackles of scale, logistics and above all, economics. A’ la Bethany Taylor, a museum can accommodate installations that crawl up and around walls, spilling outside and into the street. In the tradition of Art Guy Jack Massing, a museum can even be subsumed in a bottle and cast

Art (JEMA), a museum can fit into a location-variable box that gives the exhibiting artists the freedom to create unfettered by the shackles of scale, logistics and above all, economics. A’ la Bethany Taylor, a museum can accommodate installations that crawl up and around walls, spilling outside and into the street. In the tradition of Art Guy Jack Massing, a museum can even be subsumed in a bottle and cast  upon the seas to turn up like a Friendly Floatee on some unknown distant shore. And then there’s Yoko Ono, who in her inimitably quietly flamboyant style has spent a distinguished career teaching that like art itself, a museum can be purely conceptual like a light house or as powerfully ephemeral as shafts of light thrust thousands of feet into the stratosphere casting

upon the seas to turn up like a Friendly Floatee on some unknown distant shore. And then there’s Yoko Ono, who in her inimitably quietly flamboyant style has spent a distinguished career teaching that like art itself, a museum can be purely conceptual like a light house or as powerfully ephemeral as shafts of light thrust thousands of feet into the stratosphere casting  furtive wishes for peace to every mind and heart around the globe.

furtive wishes for peace to every mind and heart around the globe.

So there you have it. Compliments of one Forrest “Frosty” Myers and his compatriots Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain and David Novros, a museum can fit on the side of a ceramic wafer and travel like light from Ono’s Imagine Peace Tower into the depths of inner space.

What other lessons will Dellinger serve up during his  tenure as director of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery? Only time will tell. But the next iteration in his master plan unfolds October 22 through December 17 when the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery will premiere RAUSCHENBERG: China/America Mix, the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work at the Gallery since his death in 2008. Until then, get thee to the gallery for a dose of the first space object to land in Southwest Florida. There’s still much to be learned.

tenure as director of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery? Only time will tell. But the next iteration in his master plan unfolds October 22 through December 17 when the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery will premiere RAUSCHENBERG: China/America Mix, the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work at the Gallery since his death in 2008. Until then, get thee to the gallery for a dose of the first space object to land in Southwest Florida. There’s still much to be learned.

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission runs through September 27, 2014. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Saturdays. The gallery is closed on Sundays and holidays. For additional information, please call 239-489-9313 or visit www.RauschenbergGallery.com.

____________________________________________________________________

David Novros interesting choice for ‘Moon Museum’ for variety or reasons (08-15-14)

The Moon Museum (1969): Apollo XII’s Secret Art Mission opens August 22 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery. The headliner of the show is the Moon Museum, a thumbnail-sized ceramic chip that contains drawings by Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, John Chamberlain, Forrest “Frosty” Myers and David Novros. A duplicate of the chip was surreptitiously placed on the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar lander,