Fort Myers’ love affair with Edison films dates back to 1908

At sunset (8:00ish) on Friday, May 14, the Edison and Ford Winter Estates will host the Fort Myers Film Festival, screening four films on the lawn of the Henry Ford Estate. Seated outdoors along the picturesque Caloosahatchee River, guests will watch movies under the stars. The films will include an Edison silent picture, a production about the late Sam Galloway, and two feature films, Stay Wild and A Greenlander. The site is one

At sunset (8:00ish) on Friday, May 14, the Edison and Ford Winter Estates will host the Fort Myers Film Festival, screening four films on the lawn of the Henry Ford Estate. Seated outdoors along the picturesque Caloosahatchee River, guests will watch movies under the stars. The films will include an Edison silent picture, a production about the late Sam Galloway, and two feature films, Stay Wild and A Greenlander. The site is one  of several locations hosting the Film Festival occurring May 12-16.

of several locations hosting the Film Festival occurring May 12-16.

It’s an appropriate partnership given Fort Myers’ long love affair with pictorial storytelling and the man who invented much of the technology that made filmmaking possible.

The town’s fascination  with film dates back to September 1, 1908. On that date, an enterprising young man by the name of John Towles Hendry introduced Fort Myers to the realm of motion pictures in a tiny one-room affair with bench seats and a hunk of canvas tacked up on one wall. The premiere was so heavily attended that Hendry had to play the film over and over again for three solid hours while his wife provided musical accompaniment for the silent movie on an upright piano for the SRO crowds who crammed into the Royal

with film dates back to September 1, 1908. On that date, an enterprising young man by the name of John Towles Hendry introduced Fort Myers to the realm of motion pictures in a tiny one-room affair with bench seats and a hunk of canvas tacked up on one wall. The premiere was so heavily attended that Hendry had to play the film over and over again for three solid hours while his wife provided musical accompaniment for the silent movie on an upright piano for the SRO crowds who crammed into the Royal  Palm Theatre.

Palm Theatre.

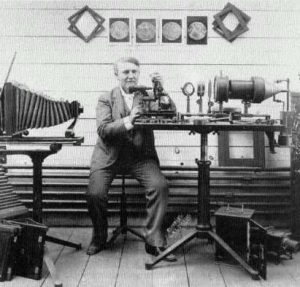

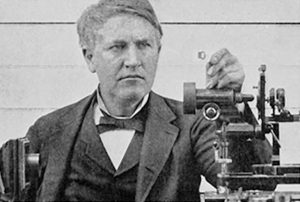

It wasn’t just the novelty of this new form of entertainment that captured Fort Myers’ fancy. Moviegoers were predisposed to love photoplays because of Thomas Edison. The town loved everything Edison. Residents, young and old, celebrated the inventor’s birthday and arrival back in town each winter with  a zeal surpassed only by Washington’s birthday, which was the biggest event each year (topping even the Fourth of July, Christmas and New Year’s Eve). And it was Thomas Alva Edison and experimental staff member William Dickson who invented a motion picture camera and a peephole viewing device called the kinetoscope in 1891, which he upgraded within a handful of years with technology capable of projecting moving images on a screen that could be viewed by an entire room full of people.

a zeal surpassed only by Washington’s birthday, which was the biggest event each year (topping even the Fourth of July, Christmas and New Year’s Eve). And it was Thomas Alva Edison and experimental staff member William Dickson who invented a motion picture camera and a peephole viewing device called the kinetoscope in 1891, which he upgraded within a handful of years with technology capable of projecting moving images on a screen that could be viewed by an entire room full of people.

Of course projectors  are nothing without the films they play, so beginning in 1896, Edison turned his attention to filmmaking, building a tarpaper-covered black filmmaking studio at his West Orange, New Jersey lab that he tongue-in-cheek called “The Doghouse.” Dickson and his co-workers gave it another name – the Black Maria – because the studio’s cramped quarters reminded them of the paddy wagons the police

are nothing without the films they play, so beginning in 1896, Edison turned his attention to filmmaking, building a tarpaper-covered black filmmaking studio at his West Orange, New Jersey lab that he tongue-in-cheek called “The Doghouse.” Dickson and his co-workers gave it another name – the Black Maria – because the studio’s cramped quarters reminded them of the paddy wagons the police  used at that time.

used at that time.

Over the next eight years, Dickson and his cohorts made hundreds of films at the Black Maria, and as word spread, performers from across the country began showing up in West Orange looking for work. Never one to miss a photo op, Edison posed with  dozens of the actors, dancers, boxers, magicians and vaudeville entertainers who made it into his films for newspaper articles promoting the films and Edison’s pioneering efforts to promote and expand the industry.

dozens of the actors, dancers, boxers, magicians and vaudeville entertainers who made it into his films for newspaper articles promoting the films and Edison’s pioneering efforts to promote and expand the industry.

The studio had a special fondness for westerns, filming two of the earliest of this genre ever made in 1899. With a run time of under a minute,  Cripple Creek Bar Room Scene featured not only a prototypical western saloon, but a barmaid played by a man. Set during the Alaska Gold Rush, Poker at Dawson City revolved around a crooked poker game and the industry’s seminal barroom fight.

Cripple Creek Bar Room Scene featured not only a prototypical western saloon, but a barmaid played by a man. Set during the Alaska Gold Rush, Poker at Dawson City revolved around a crooked poker game and the industry’s seminal barroom fight.

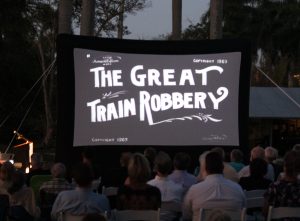

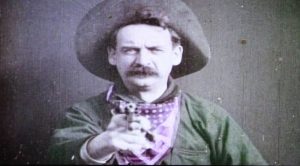

Edison closed the Black Maria in 1901 and built a glass-enclosed rooftop movie studio in New York City, but continued to make westerns from this new location including Edwin S. Porter’s groundbreaking silent short (at 12 minutes long), The Great Train Robbery, considered to be  the first American action film in history.

the first American action film in history.

Porter was a former Edison Studios cameraman, but with The Great Train Robbery, he stepped up his game, writing, directing, editing and producing the film. Porter used a number of innovative techniques, including composite editing, on-location shooting (at the South Maintain Reservation in Milltown,  New Jersey and along the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad), and frequent camera movement. The film is one of the earliest to employ cross cutting, in which two scenes are shown to be occurring simultaneously but in different locations. Some prints were also hand colored in certain scenes. And the final scene (occasionally played at the beginning) in which the leader of the bandits empties his pistol point-blank at the camera is believed to have inspired the gun barrel sequence that opens each James Bond film.

New Jersey and along the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad), and frequent camera movement. The film is one of the earliest to employ cross cutting, in which two scenes are shown to be occurring simultaneously but in different locations. Some prints were also hand colored in certain scenes. And the final scene (occasionally played at the beginning) in which the leader of the bandits empties his pistol point-blank at the camera is believed to have inspired the gun barrel sequence that opens each James Bond film.

Boasting a modest budget of just $150 (less than $5,000 in today’s money), the film became a blockbuster by modern standards and remained one of the most popular films of the silent era until the release of The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Starring Alfred C. Abadie, Broncho Billy Anderson and Justus D. Barnes (although there were no credits), The Great Train Robbery was selected in 1990

Boasting a modest budget of just $150 (less than $5,000 in today’s money), the film became a blockbuster by modern standards and remained one of the most popular films of the silent era until the release of The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Starring Alfred C. Abadie, Broncho Billy Anderson and Justus D. Barnes (although there were no credits), The Great Train Robbery was selected in 1990  for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

And fittingly, The Great Train Robbery was played for guests during the 9th Annual Fort Myers Film Festival in  2019.

2019.

Neither FMFF nor EFWE has identified which silent film it will screen for guests this year, the fun starts around sunset on Friday, May 14 on the lawn of the Mangoes along the Caloosahatchee River.

May 1, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.