“I was just thinking of something that would serve as a protector in a sense, or symbolically, for the area, for all downtown, after what we had with Hurricane Ian,”  Acevedo relates. “So I thought of the mangrove as a natural protector of the land and its natural protection of the coast. I thought the mangrove would be the ideal symbol.”

Acevedo relates. “So I thought of the mangrove as a natural protector of the land and its natural protection of the coast. I thought the mangrove would be the ideal symbol.”

In the U.S. alone, mangroves prevent $11.3 billion in property damage and protect 8,800 miles from flooding each year, with the greatest flood protection benefits occurring during tropical cyclones. According to the US Geological Survey, mangroves reduce surge heights at a rate of two to three feet per mile across the width of a mangrove forest.

“I’m not an expert by any means, but I heard many times that it’s basically what protects our coast and has all of these benefits to it.”

While The Living Lands  mosaic is an ode to the mangroves that naturally protect our coastlines, it also acknowledges that mangroves are endangered. Unfortunately, 62% of the mangroves in Southwest Florida suffered canopy damage during Hurricane Irma. While mangroves on well-drained sites (83%) re-sprouted new leaves within one year after that storm, those on poorly-drained inland sites experienced

mosaic is an ode to the mangroves that naturally protect our coastlines, it also acknowledges that mangroves are endangered. Unfortunately, 62% of the mangroves in Southwest Florida suffered canopy damage during Hurricane Irma. While mangroves on well-drained sites (83%) re-sprouted new leaves within one year after that storm, those on poorly-drained inland sites experienced  one of the largest mangrove diebacks on record (10,760 ha). No information is yet available on the damage suffered by Southwest Florida mangroves and mangrove forests as a result of Hurricane Ian. When damage from Ian is factored in, scientists fear that Southwest Florida’s mangrove population may have been pushed to the brink of collapse by the

one of the largest mangrove diebacks on record (10,760 ha). No information is yet available on the damage suffered by Southwest Florida mangroves and mangrove forests as a result of Hurricane Ian. When damage from Ian is factored in, scientists fear that Southwest Florida’s mangrove population may have been pushed to the brink of collapse by the  strong and sustained winds, storm surge, prolonged flooding, sedimentation and coastal erosion we have seen as a consequence of Hurricanes Irma and Ian.

strong and sustained winds, storm surge, prolonged flooding, sedimentation and coastal erosion we have seen as a consequence of Hurricanes Irma and Ian.

Like the Edison light bulb, royal palm and pineapple, Acevedo hopes his mangrove will one day become distinctively associated with the sustainability of our coastal ecology and our resilience as a community.

Acevedo’s Connection to the River District

David Acevedo has played an important role in bringing art to the River District in the aftermath of the four-year Streetscape project that ended in 2008. Through his DAAS Co-op Gallery, the Union Artist Studios, Arts & Eats Café at the Alliance for the Arts and as an Art Walk co-founder in 2008, Acevedo has played an instrumental role in transforming downtown Fort Myers from an infrequently-visited business district that figuratively rolled up its sidewalks after 5 p.m. to a trendy art district with a thriving nighttime economy. Against this backdrop, he’s now thrilled to have a public art presence in the town he loves so dearly.

“I feel like a contributor to the beauty of our downtown, the River District, in a sense, because there’s … a … beautiful little corner of downtown with very vibrant colors, a mural that people can take selfies on and just say, hey, I was in Fort Myers. That makes me proud.”

More, it adds to the image that the City projects to its citizens and the outside world.

“You can tell the level of culture or the level of what’s really going on in the city, the progress of the city when you see beautifully made murals and mosaics and public art sculptures and things like that. I think it elevates the quality of the area. It brings beauty into the whole spectrum of what those surroundings are, and I honestly feel it’s incredibly necessary.”

Acevedo encourages other developers to take a page from Zimmer Development’s playbook.

“In my opinion, every developer should follow that same lead. Every developer, anybody who builds something that is going to be like a primary architectural landmark in our city, should bring in also art with it … something to give back to the City or the public and the people in the community, like a beautiful sculpture or painting or mural, whatever it is. Including art in a project is not only good citizenship, it’s good business.”

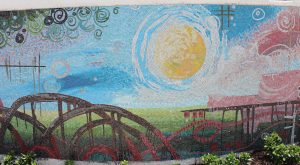

Located at the busy corner of Fowler and First in the downtown Fort Myers River District, The Living Lands is Fort Myers first largescale mosaic. Installed by Zimmer Development Company of Wilmington, North Carolina at The Ivy, a 274-unit apartment complex being constructed on the site previously owned the United Methodist Church, the mosaic measures five feet tall by twenty-five feet in

Located at the busy corner of Fowler and First in the downtown Fort Myers River District, The Living Lands is Fort Myers first largescale mosaic. Installed by Zimmer Development Company of Wilmington, North Carolina at The Ivy, a 274-unit apartment complex being constructed on the site previously owned the United Methodist Church, the mosaic measures five feet tall by twenty-five feet in  length.

length. long day at work,” Acevedo remarks. “These colors reenergize and invigorate us all and I strive to remind everyone driving by the importance of our skies.”

long day at work,” Acevedo remarks. “These colors reenergize and invigorate us all and I strive to remind everyone driving by the importance of our skies.” which represents the connections we make in life; and the swirls or circles, which represent cycles in life, memories and life experiences. There is also a faint Royal Palm, making reference to the nearby McGregor Boulevard – where I have my studio and gallery. Being an abstract-expressionistic piece,

which represents the connections we make in life; and the swirls or circles, which represent cycles in life, memories and life experiences. There is also a faint Royal Palm, making reference to the nearby McGregor Boulevard – where I have my studio and gallery. Being an abstract-expressionistic piece,  it has more elements which remain open to interpretation.”

it has more elements which remain open to interpretation.” When he got the commission, Acevedo, like so many people in Charlotte, Lee and Collier counties, was still dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Acevedo knows the financial and emotional toll of hurricanes first-hand. He lost touch with his extended family back home for three long months following Hurricane Maria. And since moving to Fort Myers in 2000, he’s also weathered Charley, Wilma and Irma. So he wanted his mosaic at The Ivy to remind folks that we have a natural buffer to hurricane-generated storm surge – mangroves.

When he got the commission, Acevedo, like so many people in Charlotte, Lee and Collier counties, was still dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Ian. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Acevedo knows the financial and emotional toll of hurricanes first-hand. He lost touch with his extended family back home for three long months following Hurricane Maria. And since moving to Fort Myers in 2000, he’s also weathered Charley, Wilma and Irma. So he wanted his mosaic at The Ivy to remind folks that we have a natural buffer to hurricane-generated storm surge – mangroves.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.