Samuel Beckett’s ‘Not I’ may be best work Stella Zuri has ever done

Anyone who’s ever seen Stella Zuri perform can’t help but be impressed. She executes the roles she undertakes with the precision of a surgeon – not with the delicacy of a Christian Bernard, but rather with the ferocity of Jack the Ripper. So it’s somewhat incongruous to cast her as Mouth in Not I because Samuel Beckett’s most emphatic stage direction for his knife-edge play is “Don’t act.”

Anyone who’s ever seen Stella Zuri perform can’t help but be impressed. She executes the roles she undertakes with the precision of a surgeon – not with the delicacy of a Christian Bernard, but rather with the ferocity of Jack the Ripper. So it’s somewhat incongruous to cast her as Mouth in Not I because Samuel Beckett’s most emphatic stage direction for his knife-edge play is “Don’t act.”

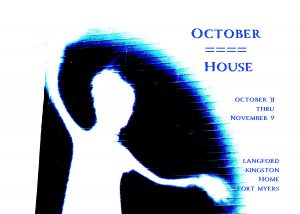

Not I is part of Ghostbird Theatre Company’s production of  October House, an aggregation of four live and one pre-recorded play on video that explores our confusion, disembodiment and helplessness in the face of an uncaring and often punitive natural world. It comes at the mid-point of the evening, in a second floor bedroom in the historic Langford Kingston Home, following a looped introductory video

October House, an aggregation of four live and one pre-recorded play on video that explores our confusion, disembodiment and helplessness in the face of an uncaring and often punitive natural world. It comes at the mid-point of the evening, in a second floor bedroom in the historic Langford Kingston Home, following a looped introductory video  of Heiner Muller’s Nightpiece, and jarring performances of Beckett’s Rockaby and Breath. Each is designed to immerse the Ghostbird audience in short, disorienting pieces that, quite frankly, play on the audience’s jangled nerves.

of Heiner Muller’s Nightpiece, and jarring performances of Beckett’s Rockaby and Breath. Each is designed to immerse the Ghostbird audience in short, disorienting pieces that, quite frankly, play on the audience’s jangled nerves.

For Not I, the audience enters a darkened bedroom and  gathers at the foot and along the side of a bed in which Zuri lies presumably strapped down under a black sheet or bedspread. It’s impossible to tell because the only thing visible in the narrow beam cast by the spotlight mounted over her right shoulder is Zuri’s mouth and the underside of her flared nostrils. It’s completely disconcerting even if you don’t suffer from claustrophobia.

gathers at the foot and along the side of a bed in which Zuri lies presumably strapped down under a black sheet or bedspread. It’s impossible to tell because the only thing visible in the narrow beam cast by the spotlight mounted over her right shoulder is Zuri’s mouth and the underside of her flared nostrils. It’s completely disconcerting even if you don’t suffer from claustrophobia.

The tension in the room is palatable. It’s virtually suffocating.

And  once the last foot has shuffled into place, words begin to tumble frantically from the lighted mouth in a helter-skelter stream of consciousness so quick and nimble that it is all but impossible to keep up. There are no pauses, not even so that Zuri can swallow. The words just keep coming and coming and coming. From dense layers of interruptions, interjections and repeated fragments a sad tale begins to emerge. It begins with ambiguous images of birth, uncaring parents and a father who vanishes into thin air. The mouth makes a reference to the godforsaken hole” into which she was born

once the last foot has shuffled into place, words begin to tumble frantically from the lighted mouth in a helter-skelter stream of consciousness so quick and nimble that it is all but impossible to keep up. There are no pauses, not even so that Zuri can swallow. The words just keep coming and coming and coming. From dense layers of interruptions, interjections and repeated fragments a sad tale begins to emerge. It begins with ambiguous images of birth, uncaring parents and a father who vanishes into thin air. The mouth makes a reference to the godforsaken hole” into which she was born  and the “godforsaken hole” into which she was banished because of her inability to communicate growing up.

and the “godforsaken hole” into which she was banished because of her inability to communicate growing up.

The story skips ahead to the woman’s old age. “Nothing of note” before that, she remarks, dismissing the entirety of her childhood and adult life. There are references to a courtroom, a mound on which she shed tears for the first time since her childhood, a desolate field in which she was forced to lay face down, and interminable buzzing and an intrusive  beam of light that haunt her and threaten to drive her and the audience mad. However, because the words recounting the story are spoken with such blazing, unpunctuated speed, only snippets and disjointed phrases register. The rest is as unintelligible as music droning in the background just out of earshot.

beam of light that haunt her and threaten to drive her and the audience mad. However, because the words recounting the story are spoken with such blazing, unpunctuated speed, only snippets and disjointed phrases register. The rest is as unintelligible as music droning in the background just out of earshot.

Beckett himself directed but one performance of Not I, and besides telling his actor not to act, he famously said, “You can’t go fast enough for me.” If one can’t listen fast enough to make out the story, how in the world is it possible for any actor to speak so fast that the audience is rendered incapable of  thinking?

thinking?

And yet, Zuri does just that!

Few actors are capable of such high-speed staccato storytelling. Even fewer are willing to tackle a script that’s close to being unlearnable. Billie Whitelaw famously broke down in rehearsals under the pressure that Beckett placed on her and Jessica Tandy (who originated the part in New York in 1972) had to have an autocue to get through the text. More, Beckett chastised her for taking 22 minutes to deliver the monologue. Zuri did it in a little more than half the time!

Zuri  said after final dress rehearsal that she runs through the fractured narrative no less than five times a day. That quantum of rehearsal is necessary to banish all vestiges of linear thinking that might operate to prevent or undermine the required steam-of-consciousness delivery mandated by Not I.

said after final dress rehearsal that she runs through the fractured narrative no less than five times a day. That quantum of rehearsal is necessary to banish all vestiges of linear thinking that might operate to prevent or undermine the required steam-of-consciousness delivery mandated by Not I.

It’s one reason the piece is so rarely performed.

At the end of Zuri’s blacked-out monologue, we’re led to the inescapable conclusion that like the woman in Not I, aren’t we all shockingly disconnected from our own thoughts, emotions and personal histories – and the community of which we aspire to be accepted?

We must take personal responsibility for some of that, no doubt. But so much more is beyond our control.

must take personal responsibility for some of that, no doubt. But so much more is beyond our control.

“We sputter,” says Ghostbird in the playbill for October House. “We are lost, sometimes frozen in uncertainty, sometimes charged with panic motion. We long to see reality, but reality renders itself elusive at the very moment of our apprehension.”

But of one thing there can be no confusion. Stella Zuri’s  performance in Not I is one of the most remarkable theatrical feats you will ever have the opportunity to witness. In fact, it may be the best work she’s ever done, and that is saying a Mouth-ful.

performance in Not I is one of the most remarkable theatrical feats you will ever have the opportunity to witness. In fact, it may be the best work she’s ever done, and that is saying a Mouth-ful.

October House is a production you must experience. It plays in the Langford-Kingston Home this weekend and next.

October 31, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.