Creating a copy of ‘The Birth of Venus’ for ‘Botticelli in the Fire’

Jonathan Johnson works at Lab Theater as their lighting and sound tech. He fashions himself as a jack of all trades (“but expert at none”). Always up for a challenge, he was relatively nonplussed when the Lab’s Artistic Director Annette Trossbach issued a surprising challenge several weeks ago. “I want you to recreate Sandro Botticelli’s masterpiece The Birth of Venus and protect the painting in a way that will allow Steven Coe to deface it during each performance without destroying the painting.”

Jonathan Johnson works at Lab Theater as their lighting and sound tech. He fashions himself as a jack of all trades (“but expert at none”). Always up for a challenge, he was relatively nonplussed when the Lab’s Artistic Director Annette Trossbach issued a surprising challenge several weeks ago. “I want you to recreate Sandro Botticelli’s masterpiece The Birth of Venus and protect the painting in a way that will allow Steven Coe to deface it during each performance without destroying the painting.”

Trossbach knew that Johnson majored in art in college. He has an Associate  Degree in graphic design and commercial art from Southern Arkansas University and had visions of moving into a studio apartment in Manhattan after graduation, where “I’d throw paint on canvases and people would come and throw money at my feet.”

Degree in graphic design and commercial art from Southern Arkansas University and had visions of moving into a studio apartment in Manhattan after graduation, where “I’d throw paint on canvases and people would come and throw money at my feet.”

It didn’t quite work out like he’d dreamt.

Ironically, in Botticelli in the Fire – on stage at the Lab through Easter Sunday, April 4 – it’s actor Steven Coe who’s throwing the paint.

Having an art degree is one thing. Recreating a life-size Renaissance  masterpiece is quite another, especially when the artist is Sandro Botticelli and that masterpiece is 5’8” by 9’2”.

masterpiece is quite another, especially when the artist is Sandro Botticelli and that masterpiece is 5’8” by 9’2”.

“Ours is actually 5 inches smaller due to accessibility issues back stage,” Johnson corrects. “But it’s still massive.”

And the scope and magnitude of the undertaking grew exponentially more massive as Johnson and cohorts immersed  themselves in the project.

themselves in the project.

First of all, Trossbach didn’t want them to just paint The Birth of Venus. She also wanted hand-painted reproductions of a cadre of other paintings the Renaissance master purportedly threw on the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497. Set designer Michael Eyth, who has a Masters in Art, provided an assist with this,  painting two de novo on his own.

painting two de novo on his own.

But the focal point of the play is The Birth of Venus, and rendering an exact copy is a tall order for even a seasoned art forger like Han van Meegeren (who famously sold one of his fake Vermeers to Nazi Field Marshal Hermann Goering during World War II) or unforgettable Provenance villain John Drewe.

Jonathan cops  to “cheating” in recreating the painting.

to “cheating” in recreating the painting.

“We projected the image on the canvas with an HD projector and I drew everything in,” Johnson confides.

The use of technology to create hyper-realistic oil and acrylic paintings has attracted its fair share of controversy in recent years.  Some modern-day realists do paint freehand, but just as many use high def computers and projectors to help them replicate 3D imagery on two-dimensional supports such as canvas, glass and metal sheets. But truth be told, the use of technology to render realistic paintings dates back to the ancients, although it was perfected by none other than Leonardo da Vinci himself.

Some modern-day realists do paint freehand, but just as many use high def computers and projectors to help them replicate 3D imagery on two-dimensional supports such as canvas, glass and metal sheets. But truth be told, the use of technology to render realistic paintings dates back to the ancients, although it was perfected by none other than Leonardo da Vinci himself.

Back  then the technology went by another name. It was known as camera obscura (meaning “dark room” in Latin). It provided a handy dandy alternative to meticulously measuring the lengths and angles of a particular subject or scene. Leonardo published the first clear description of the camera obscura in 1502 in Codex Atlanticus, a 12-volume bound set of his drawings and writings where he also talked about other inventions such as flying machines and

then the technology went by another name. It was known as camera obscura (meaning “dark room” in Latin). It provided a handy dandy alternative to meticulously measuring the lengths and angles of a particular subject or scene. Leonardo published the first clear description of the camera obscura in 1502 in Codex Atlanticus, a 12-volume bound set of his drawings and writings where he also talked about other inventions such as flying machines and  musical instruments.

musical instruments.

The device would project onto a canvas whatever its little peephole viewfinder was pointed at. All the artist had to do was trace the lines and shapes from the projected image. The the image was upside down and reversed, but still, it enabled the artist to capture an exact likeness of whatever subject he wanted to paint. [Female artists were virtually unheard of in Renaissance times.]

Although there is no documented evidence to prove it, art historians have suggested that 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Vermeer also used camera obscura to create his super-realistic paintings. But even if da Vinci or Vermeer used camera obscura to achieve photographic perspective, the image is merely a projection. They still had to possess the technical skill, eye, mastery and time to render a lifelike image within the lines provided by the camera.

Although there is no documented evidence to prove it, art historians have suggested that 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Vermeer also used camera obscura to create his super-realistic paintings. But even if da Vinci or Vermeer used camera obscura to achieve photographic perspective, the image is merely a projection. They still had to possess the technical skill, eye, mastery and time to render a lifelike image within the lines provided by the camera.

And the same  was true for Johnson.

was true for Johnson.

After drawing the outline of Venus, the winged god Zephyr, his female companion, Aura, and the female figure holding a lavish cloak to cover Venus when she reaches the shore, the next step was for Jonathan and his Lab Theater “apprentices,” Ariana Davis and Amanda Kranich – both high school art teachers – to block in the figures and other components  of the composition.

of the composition.

“Normally you paint the entire background and engraft the subjects of the painting over the top of that,” Jonathan remarks. “We didn’t have the time to do that.”

It took Botticelli roughly two years to complete his masterwork. Johnson, Davis and Kranich had to complete the reproduction in just two months.

“It was almost like  a giant paint by numbers thing.”

a giant paint by numbers thing.”

Except when you purchase a paint-by-numbers kit, the paint is included and the colors come pre-mixed. Here, Jonathan had to mix his own colors, using modern acrylics to replicate hand-ground, mineral-based pigments that no longer exist.

“I’ve always had  an eye for color,” Jonathan acknowledges. “I can look at something and know exactly what pigments I need to mix together, and in what proportions, to get the color I want.”

an eye for color,” Jonathan acknowledges. “I can look at something and know exactly what pigments I need to mix together, and in what proportions, to get the color I want.”

But the catch here was that because acrylics dry so quickly, you can only mix so much color at one time. And when you are covering 52 square feet of canvas, you’re constantly  having to mix more paint and it has to match what you mixed an hour ago or yesterday or last week!

having to mix more paint and it has to match what you mixed an hour ago or yesterday or last week!

“But what was especially daunting was the shading, the shadowing and the highlighting, especially with the folds of the fabric, where there are 12 to 15 different shades of red that go into the folds.”

The ocean that Venus  is blowing in on proved particularly problematic. It stretches across seven and one-half feet of the nine foot canvas.

is blowing in on proved particularly problematic. It stretches across seven and one-half feet of the nine foot canvas.

“I’d go across with my first swipe and by the time I got to the end, the beginning had already dried,” Jonathan recounts. “I didn’t want to water [the paint] down so that it looked like a water color. I wanted to retain the depth and thickness of the paint. I went through two bottles of  acrylic retarder because I was trying to get to the consistency I was comfortable with oils. But even so, I’d only get 30 minutes of working time – compared to the 5 minutes I was getting when we started he painting.”

acrylic retarder because I was trying to get to the consistency I was comfortable with oils. But even so, I’d only get 30 minutes of working time – compared to the 5 minutes I was getting when we started he painting.”

Johnson didn’t merely experiment with drying times. Before making his first brush stroke on the canvas, he researched how best to  use acrylics. He even made a number of calls to his old art teacher back in Illinois, Len Smith, for pointers and trade secrets, like adding a drop of water or Dawn dishwashing liquid to the pigment to extend the drying time.

use acrylics. He even made a number of calls to his old art teacher back in Illinois, Len Smith, for pointers and trade secrets, like adding a drop of water or Dawn dishwashing liquid to the pigment to extend the drying time.

He gained a greater appreciation of what Botticelli and other Renaissance masters were up against. Although Leonard Bocour and Sam  Golden did not develop acrylic paints for fine artists until 1946-1949 (under the brand of Magna paint), Botticelli and his contemporaries used a medium that dried just as fast, if not even faster. It was called egg tempera and, as the name suggests, it’s a medium in which pigment is dissolved into egg yolk.

Golden did not develop acrylic paints for fine artists until 1946-1949 (under the brand of Magna paint), Botticelli and his contemporaries used a medium that dried just as fast, if not even faster. It was called egg tempera and, as the name suggests, it’s a medium in which pigment is dissolved into egg yolk.

“It’s really tricky,” Johnson supplments. “It also dries real fast if you  don’t get the consistency just right. We had to [work with egg tempera] in college. Mine weren’t that great.”

don’t get the consistency just right. We had to [work with egg tempera] in college. Mine weren’t that great.”

On top of the challenges of scale, dimension, color mixing and impossibly short drying times, Johnson and company were also compelled to deal with the incredible detail that Botticelli built into every nook and cranny of his composition.

“When you get into the details, you discover that every single element in the painting, whether it’s the background or  the subject of the composition, is a study in and of itself – like the leaves on the tree. Every little blade of grass, every leaf, every petal on a flower is a separate study. Every single thing is over the top, and trying to recreate that is challenging.”

the subject of the composition, is a study in and of itself – like the leaves on the tree. Every little blade of grass, every leaf, every petal on a flower is a separate study. Every single thing is over the top, and trying to recreate that is challenging.”

It also warrants mentioning that Botticelli did not aspire to make his paintings visually accurate. As opposed to the hyper-realism of today, Botticelli employed an idealistic style  in which various aspects of a figure were distorted in aid of creating a more aesthetic or appealing end product. But in this regard, what was aesthetic or appealing in 1485-1487 (when Botticelli painted The Birth of Venus, although playwright Jordan Tannahill postulates that he completed the work after the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497) is different than what we think today. Judging the painting by today’s standards,

in which various aspects of a figure were distorted in aid of creating a more aesthetic or appealing end product. But in this regard, what was aesthetic or appealing in 1485-1487 (when Botticelli painted The Birth of Venus, although playwright Jordan Tannahill postulates that he completed the work after the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497) is different than what we think today. Judging the painting by today’s standards,  art critics have panned Botticelli’s Venus for a handful of reasons. Her head is cocked at a weird angle. Her neck is elongated. One shoulder is much lower than the other. And her right arm is bent at an unnatural angle. This required Johnson, Davis and Kranich to suspend present-day artistic sensibilities in order to pay homage to Botticelli’s actual rendering.

art critics have panned Botticelli’s Venus for a handful of reasons. Her head is cocked at a weird angle. Her neck is elongated. One shoulder is much lower than the other. And her right arm is bent at an unnatural angle. This required Johnson, Davis and Kranich to suspend present-day artistic sensibilities in order to pay homage to Botticelli’s actual rendering.

But it worked.

But it worked.

They finished their “Botti-faki” with four days to spare (finishing at midnight on Monday of tech week).

But wait. There’s more.

Trossbach had one more bombshell to drop.

“We had to find a way to protect the finished painting so that it could be destroyed each night,” Johnson points out.

“We had to find a way to protect the finished painting so that it could be destroyed each night,” Johnson points out.

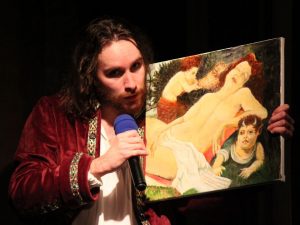

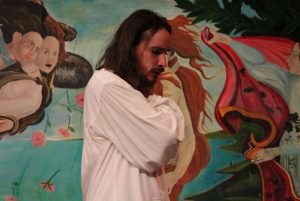

After Botticelli sells out his young friend and lover, Leonardo da Vinci, in order to save himself from castration, the artist defaces his masterpiece by throwing paint all over the canvas. In the script, playwright Jordan Tannahill provides a director’s note that mandates that the painting look like a Jackson Pollock  painting at the end of Botticelli’s tirade. So Johnson had to find a way to protect the finished painting from permanent damage from the paint that Steven Coe tosses all over his masterpiece during this scene.

painting at the end of Botticelli’s tirade. So Johnson had to find a way to protect the finished painting from permanent damage from the paint that Steven Coe tosses all over his masterpiece during this scene.

This necessitated more research, which included hours upon hours watching YouTube tutorials, including a number posted by Baumgartner  Restorations, the oldest conservation studio in Chicago. He finally settled on polyurethane. But not all polyurethanes are created equally. Some yellow a painting. Others can create a blinding glare under the theater’s overhead and spotlights.

Restorations, the oldest conservation studio in Chicago. He finally settled on polyurethane. But not all polyurethanes are created equally. Some yellow a painting. Others can create a blinding glare under the theater’s overhead and spotlights.

So far, the polyurethane has done its job. The painting still looks like new.

Or to be more precise, it looks like, well, Botticelli’s masterpiece The Birth of Venus.

Or to be more precise, it looks like, well, Botticelli’s masterpiece The Birth of Venus.

And that’s a feat few other theaters would have the audacity to attempt, never mind pull off.

But the result is so worth it.

For most of the first act, Trossbach and company tease the audience, only showing them the back of the painting or glimpses that are shrouded by a  blanket or sheet that’s draped over the artwork. When the painting is finally revealed, it elicits gasps of astonishment from the audience – and most don’t even know that it’s an actual repro that was painted just for this show.

blanket or sheet that’s draped over the artwork. When the painting is finally revealed, it elicits gasps of astonishment from the audience – and most don’t even know that it’s an actual repro that was painted just for this show.

“I’m just thrilled to have been part of the effort. I have to thank Annette for pushing us and having confidence we could pull it off. It was a team effort. As a tech person, I like to stay behind the scenes. Like the bass player in a rock and roll  band. If nobody notices you, you’ve done your job.”

band. If nobody notices you, you’ve done your job.”

That may be true, but people are sitting up and taking notice of the painting.

Look, the writing, direction and acting make Botticelli in the Fire an unqualified theatrical triumph. But ya gotta see this show if for no other reason than to appreciate what Jonathan Johnson, Ariana Davis, Amanda Kranich and Michael Eyth were able to recreate.

Botticelli in the Fire  runs through April 4.

runs through April 4.

March 17, 2021.

N.B.: Botticelli has only been performed previously once before, by Wooly Mammoth Theatre, which blew up multiple, considerably smaller copies of the original painting.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.