To assimilate or not to assimilate, that is the question in ‘Tempest’

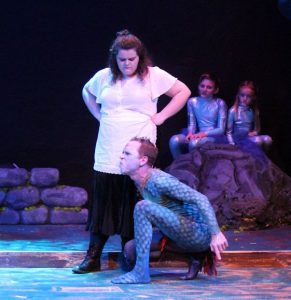

Lab Theater has on stage until November 20 Shakespeare’s The Tempest, one of the Bard’s last plays. With a plot that is centered around magic and fanciful celestial beings, Lab’s production of the play provides a veritable feast for the eyes and stimuli for the imagination. But the play possesses considerable metaphorical content, especially when viewed from the vantage of present-day social and political sensibilities. Viewed in this context, The Tempest speaks volumes to our insistence that

Lab Theater has on stage until November 20 Shakespeare’s The Tempest, one of the Bard’s last plays. With a plot that is centered around magic and fanciful celestial beings, Lab’s production of the play provides a veritable feast for the eyes and stimuli for the imagination. But the play possesses considerable metaphorical content, especially when viewed from the vantage of present-day social and political sensibilities. Viewed in this context, The Tempest speaks volumes to our insistence that  immigrants to the United States learn the English language, adopt American political values, identify as Americans and embrace American culture.

immigrants to the United States learn the English language, adopt American political values, identify as Americans and embrace American culture.

First produced in 1611, The Tempest is a story about betrayal, love, forgiveness and redemption. But, perhaps unexpectedly, the play also speaks to universal desire by all creatures to life and liberty and to the  chauvinism and arrogance exhibited by even the most benevolent colonizers.

chauvinism and arrogance exhibited by even the most benevolent colonizers.

In the context of The Tempest, this aspect of the play revolves around a beautiful celestial spirit named Ariel and a creature called Caliban. Until twelve years ago, they inhabited a magical Mediterranean island off the coast of Italy. But then a powerful sorcerer named Prospero arrived. Once the Duke of Milan, Prospero and his three-year-old daughter, Miranda, were banished there by Prospero’s brother, Antonio,  after the latter usurped the throne. And although Prospero provided Ariel, Caliban and the island’s other inhabitants the gifts of language and knowledge, they were nevertheless subject to Prospero’s whim and caprice.

after the latter usurped the throne. And although Prospero provided Ariel, Caliban and the island’s other inhabitants the gifts of language and knowledge, they were nevertheless subject to Prospero’s whim and caprice.

Ariel yearns for liberty, but sees a path to winning her freedom by doing Prospero’s bidding. Caliban sees no other  escape to his own enslavement than to overthrow his oppressor, and so he conspires with two shipwrecked castaways to murder Prospero and all else who would keep him enslaved.

escape to his own enslavement than to overthrow his oppressor, and so he conspires with two shipwrecked castaways to murder Prospero and all else who would keep him enslaved.

Proud to a fault, Caliban finds no favor in the knowledge he’s received or the language that Prospero has taught him. In the latter regard, he snarls at one point (Scene 2, Act 1 to be precise), “You taught me language, and my profit on’t is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you for learning me your language!”

Shakespeare wrote  The Tempest during a period of British conquest and colonization. Just four years before Shakespeare completed the play, a London company had sent three ships filled with settlers to present-day Virginia, where they founded Jamestown on an island in a river. Not only did those settlers have myriad interactions with the Native Americans they encountered, but so did the settlers who founded Quebec a year later and Henry Hudson as he anchored off Manhattan Island

The Tempest during a period of British conquest and colonization. Just four years before Shakespeare completed the play, a London company had sent three ships filled with settlers to present-day Virginia, where they founded Jamestown on an island in a river. Not only did those settlers have myriad interactions with the Native Americans they encountered, but so did the settlers who founded Quebec a year later and Henry Hudson as he anchored off Manhattan Island  in 1609 before setting sail up the river that now bears his name. While the settlers in Virginia and Quebec did establish trade with the natives they encountered, they took the lands they wanted in derogation of the Indians’ previous and superior claims of ownership.

in 1609 before setting sail up the river that now bears his name. While the settlers in Virginia and Quebec did establish trade with the natives they encountered, they took the lands they wanted in derogation of the Indians’ previous and superior claims of ownership.

The Bard was apparently cognizant of the opposing perspectives of these colonizers (represented in The Tempest by Prospero and “civilized” people who descended upon the island after their shipwreck)  and the people they sought to subjugate (represented by Caliban, Ariel and her celestial entourage). Interestingly, Caliban is postulated as being more beast than man just as Native Americans were often characterized as bloodthirsty savages and marauding outlaws by the politicians and press who sought to oust them from their lands.

and the people they sought to subjugate (represented by Caliban, Ariel and her celestial entourage). Interestingly, Caliban is postulated as being more beast than man just as Native Americans were often characterized as bloodthirsty savages and marauding outlaws by the politicians and press who sought to oust them from their lands.

This was certainly  the experience in Southwest Florida of Chief Billy Bowlegs and the ragtag remnants of the Seminole and Miccosukee nations in the years leading up to the establishment of Fort Myers on the southern bank of the Caloosahatchee River in 1850 for the express purpose of compelling their removal from the lands that had been accorded them by military order in 1842 at the end of the Second Seminole War.

the experience in Southwest Florida of Chief Billy Bowlegs and the ragtag remnants of the Seminole and Miccosukee nations in the years leading up to the establishment of Fort Myers on the southern bank of the Caloosahatchee River in 1850 for the express purpose of compelling their removal from the lands that had been accorded them by military order in 1842 at the end of the Second Seminole War.

The parallels between  Caliban and Billy Bowlegs are more than just passing. Like Caliban, Chief Bowlegs never viewed the Angelo settlers who poured into Florida as benefactors. Like Caliban, he regarded their language as both a symbol of their oppression and a tool for depriving him and his people of their own unique culture and heritage.

Caliban and Billy Bowlegs are more than just passing. Like Caliban, Chief Bowlegs never viewed the Angelo settlers who poured into Florida as benefactors. Like Caliban, he regarded their language as both a symbol of their oppression and a tool for depriving him and his people of their own unique culture and heritage.  But that point was lost on the Florida politicians and federal soldiers who wanted Bowlegs and his people gone – as illustrated by what happened when an Indian agent by the name of Luther Blake tried to bribe Billy Bowlegs into relocating his people to a reservation out west with a lavish Manhattan shopping trip, fine dining, copious amounts of claret and French brandy and a generous relocation fee. The Chief took

But that point was lost on the Florida politicians and federal soldiers who wanted Bowlegs and his people gone – as illustrated by what happened when an Indian agent by the name of Luther Blake tried to bribe Billy Bowlegs into relocating his people to a reservation out west with a lavish Manhattan shopping trip, fine dining, copious amounts of claret and French brandy and a generous relocation fee. The Chief took  the clothing. Operating under the pseudonym of William B. Leggs, Billy enjoyed the food and drank the brandy and fine wine. But when he returned to Southwest Florida, the wily warrior disappeared back into the Big Cypress having no intention of accepting filthy lucre for the lands he and his people had earned through the blood, sweat and

the clothing. Operating under the pseudonym of William B. Leggs, Billy enjoyed the food and drank the brandy and fine wine. But when he returned to Southwest Florida, the wily warrior disappeared back into the Big Cypress having no intention of accepting filthy lucre for the lands he and his people had earned through the blood, sweat and  tears.

tears.

Little has apparently changed since Shakespeare’s time or that of Billy Bowlegs. There remains in this country the arrogance and chauvinism of colonizers. In our case, it manifests in the impetus to strip immigrants and other minority populations of their language and culture in the ongoing and uncompromising insistence that they assimilate our “patently  superior” culture and social mores.

superior” culture and social mores.

Admittedly, this whole colonization-subjugation-assimilation thing is just a sub-theme in a play that’s more about betrayal, forgiveness, love and redemption. Go for the magic. Go because The Tempest is a feast for the eyes. Go because the acting is as wonderful as Lab audiences have come to expect of any play directed by Annette Trossbach. Go to see a cast anchored by accomplished Shakespearean actors like John McKerrow, Jack Weld, Dr. Ken Bryant and Justin Larsche (who will forever after be known as the Shakespearean Smeagol). But as we watch Lab Theater’s production of The Tempest, it seems inescapable that  we also ponder whether we are not equally deserving of Caliban’s refrain, “You taught me language, and my profit on’t is I know how to curse; the red plague rid you for learning me your language”?

we also ponder whether we are not equally deserving of Caliban’s refrain, “You taught me language, and my profit on’t is I know how to curse; the red plague rid you for learning me your language”?

You be the judge.

November 14, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.