‘When We Were Young and Unafraid’ most consequential SWFL play this season

When We Were Young and Unafraid opens on March 30th Tobye Studio Theatre in Naples. It is perhaps the most significant play to be produced anywhere in Southwest Florida during the 2021-2022 season.

When We Were Young and Unafraid opens on March 30th Tobye Studio Theatre in Naples. It is perhaps the most significant play to be produced anywhere in Southwest Florida during the 2021-2022 season.

What makes Young and Unafraid so consequential is the light it shines on the tremendous strides we’ve made in the level and quality of care and support we now provide to survivors of domestic violence. House of Cards writer Sarah Treem  does this by taking us 50 years back in time to a bed and breakfast in the Pacific Northwest that doubles as a safe house for women fleeing domestic violence. It is run by a woman named Agnes with the help of her 16-year-old daughter, Penny.

does this by taking us 50 years back in time to a bed and breakfast in the Pacific Northwest that doubles as a safe house for women fleeing domestic violence. It is run by a woman named Agnes with the help of her 16-year-old daughter, Penny.

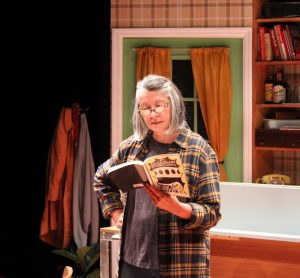

Agnes is portrayed by actor Paulette Oliva, who offers this insight into her character’s backstory and  motivations:

motivations:

“At 16, she lied about her age and joined the Army to become a nurse. So I think she really had a servant’s heart right from the very beginning, and as a nurse in France and being trained in the Army, I think that she saw a lot and she wanted to make the world a better place and I think that she realized that she could do this by harboring these women in a safe house.”

But remember,  this is 1972, and Agnes has no formal education or training in helping the victims of domestic abuse. Neither existed at that point in time. So she’s forced to rely on her training as an Army nurse and the lessons she’s learned, in Oliva’s words, in the school of hard knocks.

this is 1972, and Agnes has no formal education or training in helping the victims of domestic abuse. Neither existed at that point in time. So she’s forced to rely on her training as an Army nurse and the lessons she’s learned, in Oliva’s words, in the school of hard knocks.

The former comes in handy when a 26-year-old by the name of Mary Anne arrives at the B&B with a gruesome cut beneath her right eye. As Agnes stitches the gash without benefit of anesthesia, she tells Mary Anne  that’s she’s welcome to stay for as long as she wants – provided she stays in her room during the day, resting, reading and watching TV.

that’s she’s welcome to stay for as long as she wants – provided she stays in her room during the day, resting, reading and watching TV.

Agnes is not being mean. The B&B gives her the financial means to operate her safe harbor and guests don’t want to be confronted during their sylvan retreat with visible evidence of domestic violence. But it’s also necessary to protect her girls’ from prying eyes.

her girls’ from prying eyes.

We now know that it’s crucial for domestic violence survivors to quickly establish a seemingly normal daily routine. In fact, emergency shelters, like CARE in Collier County and ACT in Lee, require every survivor to get a job or go back to school as a condition to their ongoing residency. Survivors need a reason to get up and get out of bed.

Don’t  misunderstand. Agnes is a true hero in this story, and she’s doing her very best to protect and to help Mary Anne and the other women who seek shelter at her B&B. Naples Players’ Director Emma Canalese provides context:

misunderstand. Agnes is a true hero in this story, and she’s doing her very best to protect and to help Mary Anne and the other women who seek shelter at her B&B. Naples Players’ Director Emma Canalese provides context:

“You have to think about the time when [the play] was set. The way we look at these events now wasn’t the same, and so she developed her own methodology to help these women and understood that there were  certain tacks she had to take because there are patterns and she’s starting to recognize the patterns.”

certain tacks she had to take because there are patterns and she’s starting to recognize the patterns.”

The most intransigent of these patterns is the sobering fact that the typical domestic violence survivor goes back to their abuser seven times before they are finally ready to leave for good … assuming they’re not dead by then. Mary Anne herself gives voice to why this is. In spite of the abuse, she’s still in love with her husband. He makes her feel desirable.  So she makes excuses for the abuse – he came back from Vietnam a different man, but she believes that the man she fell in love with is still in there and will return to her if she gives him more understanding, more patience, more time.

So she makes excuses for the abuse – he came back from Vietnam a different man, but she believes that the man she fell in love with is still in there and will return to her if she gives him more understanding, more patience, more time.

And so the yellow telephone sitting on a desk in a tiny alcove next to the kitchen door takes on the importance of a separate character in the play. You can almost hear it beckoning to  her in the candlelight. Call your husband if, for nothing else, just to hear his voice.

her in the candlelight. Call your husband if, for nothing else, just to hear his voice.

What Mary Anne needs even more than a safe haven is counseling, but that’s the one thing that Agnes is ill-equipped to provide. Paulette Oliva explains:

“Her approach [to the girls who she takes in] is very clinical.  She has to be that way because if she allows herself to be involved, or the people that she loves to be involved, there could be dire circumstances. And you can see how that turns out in the play.”

She has to be that way because if she allows herself to be involved, or the people that she loves to be involved, there could be dire circumstances. And you can see how that turns out in the play.”

In fact, by segregating Mary Anne from the B&B’s guests and essentially depriving her of anybody to talk to, Agnes unwittingly engages in secondary victimization. All too frequently, the negative way in which survivors are treated erodes their resolve to forge ahead and make a new life. In the absence of emotional support, they cannot grieve over the loss of their relationship. And without that closure, a low-self-esteem domestic violence survivor like Mary Anne will inevitably return to her abuser – or end up in another abusive relationship.

survivors are treated erodes their resolve to forge ahead and make a new life. In the absence of emotional support, they cannot grieve over the loss of their relationship. And without that closure, a low-self-esteem domestic violence survivor like Mary Anne will inevitably return to her abuser – or end up in another abusive relationship.

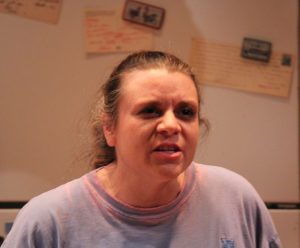

A new mom herself, Amy Hughes was eager to play the part of Mary Anne.

She makes this important observation about the play:

“Not everything is wrapped up in a perfect bow and I think that that’s important because that’s life. There is no perfect villain or hero in this story. Everybody has their very human element, and I think that that’s important because people are going to see themselves represented in there … They’re going to see that not everything works out the way you think it’s going to be. And that’s okay. You learn and grow.”

“Not everything is wrapped up in a perfect bow and I think that that’s important because that’s life. There is no perfect villain or hero in this story. Everybody has their very human element, and I think that that’s important because people are going to see themselves represented in there … They’re going to see that not everything works out the way you think it’s going to be. And that’s okay. You learn and grow.”

Thematic content aside,  When We Were Young and Unafraid is characterized by sophisticated writing, conversational dialogue and well-developed, genuine and highly-relatable characters. That’s actually one of the chief reasons that Emma Canalese wanted to direct the play:

When We Were Young and Unafraid is characterized by sophisticated writing, conversational dialogue and well-developed, genuine and highly-relatable characters. That’s actually one of the chief reasons that Emma Canalese wanted to direct the play:

“I have met every single one of the women in the play, and most of the women at some point, maybe just not to  the same degree and even, particularly over the last couple of years I feel that I really understand Agnes more because there have been several personal experiences come up where I have taken on a role of helping people out of situations and because it seems to be the never-ending story and I think it’s an important one to tell.”

the same degree and even, particularly over the last couple of years I feel that I really understand Agnes more because there have been several personal experiences come up where I have taken on a role of helping people out of situations and because it seems to be the never-ending story and I think it’s an important one to tell.”

Although still a week away from the play’s opening, the acting in this play is brilliant across the board. Oliva, Hughes,  Giszelle Kirton, Shelley Gothard and Bernardo Santana do justice to Treem’s prose, characterization and plot (in which Treem uses long silent pauses in the action and dialogue to heighten the tension and keep the audience teetering on the edge of their seats).

Giszelle Kirton, Shelley Gothard and Bernardo Santana do justice to Treem’s prose, characterization and plot (in which Treem uses long silent pauses in the action and dialogue to heighten the tension and keep the audience teetering on the edge of their seats).

The fact that The Naples Players are bringing this play to stage right now is also poignant. Toward the end of the play, a  character by the name of Hannah effuses over the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, saying that the times, they are a-changing. She could just as well have been talking about the re-authorization of the Violence Against Women’s Act just nine days ago, something that shocks Director Emma Canalese:

character by the name of Hannah effuses over the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, saying that the times, they are a-changing. She could just as well have been talking about the re-authorization of the Violence Against Women’s Act just nine days ago, something that shocks Director Emma Canalese:

“It’s a little crazy to me that the Violence Against Women’s Act just had to be renewed in what, the last two years. Why did it  have to be renewed? Why is that something that’s still coming up? I didn’t think that there was a stopping date for that to happen, but apparently it’s something we have to keep revisiting. And that’s why, I think, the months that we look at this happening and also stories like this are important because this is a story that has always been around and seemingly will continue unless we keep talking about it and keep saying these words out loud that this is continuing to happen.”

have to be renewed? Why is that something that’s still coming up? I didn’t think that there was a stopping date for that to happen, but apparently it’s something we have to keep revisiting. And that’s why, I think, the months that we look at this happening and also stories like this are important because this is a story that has always been around and seemingly will continue unless we keep talking about it and keep saying these words out loud that this is continuing to happen.”

When it comes to domestic violence, the Violence Against Women’s Act is a really big deal. Since its initial passage in 1994, incidents of domestic violence and sexual assault have declined significantly. But access to services, the availability of emergency shelters, and justice for survivors depends in large part on the funding provided by the Act, which sunsets for the fifth time in 2027.

the availability of emergency shelters, and justice for survivors depends in large part on the funding provided by the Act, which sunsets for the fifth time in 2027.

Without adequate funding, domestic violence survivors could once again find themselves scrambling for safety and support just as they did in 1972.

In the play, Agnes delivers a cautionary note. When Hannah tells her the times they are a changing, she soberly replies “They’ll change back.”

And that’s why  plays like When We Were Young and Unafraid are so consequential. In that vein, Mary Anne’s alter ego, Amy Hughes, thinks everyone should see this show.

plays like When We Were Young and Unafraid are so consequential. In that vein, Mary Anne’s alter ego, Amy Hughes, thinks everyone should see this show.

“I think the show is important for everyone, male, female, other, doesn’t matter. Everybody, especially women, we all have a story of being abused or pushed past our comfort and I think it’s important for  women to see that in each other and then also for men to understand it. So, it’s going to make you feel uncomfortable and that’s a good thing because in the discomfort, there’s knowledge, there’s growth, there’s understanding and I think we all need that right now.

women to see that in each other and then also for men to understand it. So, it’s going to make you feel uncomfortable and that’s a good thing because in the discomfort, there’s knowledge, there’s growth, there’s understanding and I think we all need that right now.

Domestic violence facts and figures:

- There are five emergency shelters in operation in Southwest Florida – two in Collier County (one in Naples and the other in Immokalee), two in Lee County (one if Fort Myers and the other in Cape Coral) and one in Charlotte County.

- Each emergency shelter provides accommodations for minor

children and pets. In the latter regard, they include kennels, dog runs and related facilities.

children and pets. In the latter regard, they include kennels, dog runs and related facilities. - In an effort to facilitate a survivor’s return to a functional daily routine, emergency shelters provide survivors with access to a kitchen and fully-stocked pantry so that they can cook meals any time they want.

- The average domestic violence survivor spends 47 days in an emergency shelter.

- The emergency hotlines operated by our local shelters receive and average of 13 calls every minute.

- In 2019,

Florida’s domestic violence centers provided 563,721 nights of emergency shelter to 13,250 survivors and their children.

Florida’s domestic violence centers provided 563,721 nights of emergency shelter to 13,250 survivors and their children. - There exists a chronic shortage of domestic violence shelter beds.

- No one is immune from domestic violence. Every race, ethnicity, religion and socio-economic demographic is affected by domestic violence, and one in seven men will suffer domestic violence at the hands of their partner.

- Domestic violence is the most common type of violent crime committed in the United States.

- Incidents

of domestic violence increased by 8 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic.

of domestic violence increased by 8 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic. - Domestic violence costs $10 Billion annually in the United States.

- In Collier County, the cost was $32.4 million in 2020, with $19.8 million allocable to law enforcement and $9.2 million to medical costs.

- Asking why someone subjected to domestic violence didn’t leave or returned to their abuser is a form of victim shaming and actually contributes to a survivor’s decision to either remain in or return to an abusive relationship.

- Both

emotional and financial support are vital to empowering a survivor to truly end an abusive relationship.

emotional and financial support are vital to empowering a survivor to truly end an abusive relationship. - Finances are used as a weapon by abusers in 99 percent of all domestic violence cases.

- The ability of domestic violence survivors to leave and end abusive relationships is further complicated in the undocumented community by language barriers, fear of deportation and a machismo culture that teaches girls and young women to be subservient to men.

- As When We Were Young and Afraid intimates, many abusers possess narcissistic personalities that are characterized by lack of empathy, arrogance, entitlement and exploitation. The play includes a character who engages in a classic “red flag” behavior known as “love bombing” – in which he showers a vulnerable woman with flattery, compliments and idealization (“I’ve never met anyone like you”), all designed to get the potential victim to trust him.

- But idealization is typically followed by devaluation and then isolation of the victim from family and friends.

- The Violence Against Women’s Act was first enacted in 1994.

- VAWA was reauthorized in 2000, 2005 and 2013.

- After being allowed to lapse in 2019, VAWA was reauthorized on Wednesday, March 19, 2022 as part of the Fiscal Year 2022 omnibus package that funds the federal government for the next eight months.

- As reauthorized, VAWA extends and even increases the funding limits of many of the Act’s grant programs, many of which support the services provided by domestic violence emergency shelters like the ones serving Southwest Florida.

- As reauthorized, VAWA increases services and support for survivors from underserved and marginalized communities, (including the LGBTQ+ community), survivors of dating violence, and victims of sexual assault and stalking.

- As reauthorized, VAWA now provides a federal cause of action for cyberabuse and cyberstalking.

- It also improves the healthcare system’s response to domestic violence and sexual assault.

- In addition to VAWA, the American Rescue Plan recently provided $1 billion in supplemental funding for domestic violence and sexual assault in response to the increased number of domestic violence cases occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic. (See above.)

- The play raises by implication a number of other questions such as what type of issues are domestic violence emergency shelters seeing in the survivors who come to them; how would the decreased availability of abortion services affect incidents of domestic violence and complicate a survivor’s decision to leave and end an abusive relationship; and how would a vigilante/bounty provision like that included in the Texas abortion legislation impact the services provided by domestic violence emergency services?

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.