‘Women Who Mapped the Stars’ about the quest of 5 female astronomers to be heard and respected

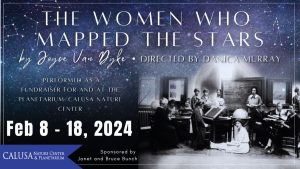

The Women Who Mapped the Stars is coming to Southwest Florida in February. But it is not being performed in the Foulds Theatre. Instead, it will be staged as a fundraiser for and is being performed at the Calusa Nature Center and Planetarium.

The Women Who Mapped the Stars is coming to Southwest Florida in February. But it is not being performed in the Foulds Theatre. Instead, it will be staged as a fundraiser for and is being performed at the Calusa Nature Center and Planetarium.

The play follows five extraordinary women who changed the way  we see the universe — and women scientists in general. At its heart, The Women Who Mapped the Stars is a drama about the desire of significant female astronomers to be heard … and respected.

we see the universe — and women scientists in general. At its heart, The Women Who Mapped the Stars is a drama about the desire of significant female astronomers to be heard … and respected.

In this respect, the play possesses the same sensibilities as Margot Lee Shetterly’s bestselling book and Academy  Award-winning film adaptation, Hidden Figures, and its female astronaut analog, Mercury 13. In fact, Hidden Figures contains a recurring scene in which a NASA human computer by the name of Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson continually tries to have the reports she writes published in her name only to be told “that’s not how it’s done around here.”

Award-winning film adaptation, Hidden Figures, and its female astronaut analog, Mercury 13. In fact, Hidden Figures contains a recurring scene in which a NASA human computer by the name of Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson continually tries to have the reports she writes published in her name only to be told “that’s not how it’s done around here.”

Like Katherine and the other women depicted in Hidden Figures as well as Mercury 13, the female scientists portrayed in Women Who Mapped the Stars are chagrined to see their male superiors and counterparts take credit for their work product, their discoveries, their contributions to the field of astronomy.

Like Katherine and the other women depicted in Hidden Figures as well as Mercury 13, the female scientists portrayed in Women Who Mapped the Stars are chagrined to see their male superiors and counterparts take credit for their work product, their discoveries, their contributions to the field of astronomy.

That’s also what routinely happened to Willamina Flemming, Henrietta Swan Levitt, Annie Jump Cannon and Antonia Maury. They worked more than a century ago at the Harvard Observatory under the direction of Edward Charles Pickering. It was not bad enough that Pickering built the Observatory’s stellar reputation on the strength of their body of work. Worse still, he countenanced them being labelled

That’s also what routinely happened to Willamina Flemming, Henrietta Swan Levitt, Annie Jump Cannon and Antonia Maury. They worked more than a century ago at the Harvard Observatory under the direction of Edward Charles Pickering. It was not bad enough that Pickering built the Observatory’s stellar reputation on the strength of their body of work. Worse still, he countenanced them being labelled  “Pickering’s Harem,” prompting Maury to retort, “Something rises up much deeper than bile.”

“Pickering’s Harem,” prompting Maury to retort, “Something rises up much deeper than bile.”

Cecilia Payne discovered that stars are comprised of hydrogen. She advanced this hypothesis in her doctoral thesis, which was characterized years later as “the most brilliant Ph.D thesis ever written in astronomy.” But at the time she advanced her theories in 1925, no one found either her or her conclusions credible. However, a male contemporary found her  work so meritorious that he appropriated her work and claimed credit for her discoveries.

work so meritorious that he appropriated her work and claimed credit for her discoveries.

Sadly, men have been misappropriating the work and discoveries of women for centuries. Art history is replete with infamous stories. For example, most of the luminous portraits of female Italian Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola were attributed to the man who officially served as the court painter during  the reign of King Phillip II of Spain. The rest were mistakenly attributed to Titian and Zurbaran, marginalizing Sofonisba Anguissola and her efforts to pave the way for women to become professional artists at a time and place when this was unfathomable.

the reign of King Phillip II of Spain. The rest were mistakenly attributed to Titian and Zurbaran, marginalizing Sofonisba Anguissola and her efforts to pave the way for women to become professional artists at a time and place when this was unfathomable.

Sofonisba Anguissola’s plight is not an aberration. Rather, it is an all-too-common occurrence. Artemisia Gentileschi’s Italian Baroque paintings were attributed to her father. Most of Dutch painter Judith Leyster’s  35 surviving genre scenes and portraits were misattributed to either her teacher, Frans Hals, or her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer. And French Neoclassical painter Marie-Denise Villers’ works have similarly been attributed to her art instructor, Jacques-Louis David.

35 surviving genre scenes and portraits were misattributed to either her teacher, Frans Hals, or her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer. And French Neoclassical painter Marie-Denise Villers’ works have similarly been attributed to her art instructor, Jacques-Louis David.

The five brilliant female astronomers depicted in The Women Who Mapped the Stars are painfully aware of the ways in which the worlds of science and academia are stacked against them. But they also harbor the hope that they and others like them will effect transformational social changes given enough time. Here, too, playwright Joyce Van Dyke calls upon the character of Antonia Maury to articulate this profound prophecy, ““A hundred years from now, 1990, women will be paid the same as men and we’ll look back, appalled.”

Mapped the Stars are painfully aware of the ways in which the worlds of science and academia are stacked against them. But they also harbor the hope that they and others like them will effect transformational social changes given enough time. Here, too, playwright Joyce Van Dyke calls upon the character of Antonia Maury to articulate this profound prophecy, ““A hundred years from now, 1990, women will be paid the same as men and we’ll look back, appalled.”

Frankly, Fleming, Payne, Maury, Cannon and Leavitt would be the ones who are appalled. In 2022, women still earned only 82 cents for every dollar a man makes, with Black and Hispanic women making just 56 cents for every dollar that white, non-Hispanic men earn. A 20-year-old woman just starting full-time, year-round work stands to lose $407,760 over a 40-year career compared to her male counterpart. In fact, the Institute for Women’s Policy Research projects that gender pay equity won’t become a reality until 2059.

The one area in which Women Who Mapped the Stars deviates from Hidden Figures’ award-winning recipe is backstory. In Figures, author Margot Lee Shetterly contrasts each character’s work-place struggle to be taken seriously and treated as equals with the challenges they negotiated in their personal lives. Van Dyke doesn’t reveal much about the personal lives of her five female astronomers, opting to focus instead on their professional travails and triumphs. But given that the play will be staged inside the Calusa Nature Center and Planetarium and produced as a 90-minute one-act show, there really isn’t the time to delve into, and audiences may not need to know, each character’s backstory and personal backdrop to enjoy the production.

The Women Who Mapped the Stars runs February 8 through the 18.

Go here for play dates, times and ticket information.

January 28, 2024.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.