Don ‘D.J.’ Wilkins was ‘the right guy in the right place at the right time’

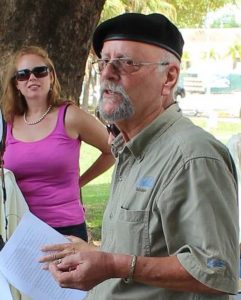

For a quarter of a century, the name Don D.J. Wilkins was synonymous with public art in the City of Fort Myers. Proclaimed the “Sculptor of Fort Myers” by former mayor Art Hammel and the City Council that served during his administration, Wilkins was responsible for designing, fabricating and installing 23 sculptures and art installations throughout the City during a 30-year span that began in 1983, as well as restoring three other important aesthetic landmarks in an age that pre-dated the discipline of art conservation. Wilkins died on Sunday, October 10 at the age of 76.

For a quarter of a century, the name Don D.J. Wilkins was synonymous with public art in the City of Fort Myers. Proclaimed the “Sculptor of Fort Myers” by former mayor Art Hammel and the City Council that served during his administration, Wilkins was responsible for designing, fabricating and installing 23 sculptures and art installations throughout the City during a 30-year span that began in 1983, as well as restoring three other important aesthetic landmarks in an age that pre-dated the discipline of art conservation. Wilkins died on Sunday, October 10 at the age of 76.

Identified by his trademark black beret, jaunty gait and throaty laugh,  Wilkins start in public art was improbable. Before relocating to Fort Myers in 1975, D.J. worked in heating, ventilation and air conditioning in Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he was teaching students skills like welding as part of a stint in the Job Corps.

Wilkins start in public art was improbable. Before relocating to Fort Myers in 1975, D.J. worked in heating, ventilation and air conditioning in Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he was teaching students skills like welding as part of a stint in the Job Corps.

Wilkins gave credit to his mom for his decision to move to Fort Myers.

“‘Fort Myers is the prettiest place I’d ever seen,’ she told me once,” D.J. recalled in a 2012 interview.

But it was a “hippie friend” on Fort Myers Beach who planted the seed for  his sculpting career when he showed Don art that he’d created from cypress and driftwood. A short time later, the two of them hopped into a 1960 GMC pickup truck and drove to a Naples gallery, where Wilkins saw sculptures that inspired him to become an artist. Still, art was merely a hobby until a chance meeting with artist Greg Biolchini in 1979 prompted Wilkins to quit the air-conditioning business and apply himself to sculpture full-time.

his sculpting career when he showed Don art that he’d created from cypress and driftwood. A short time later, the two of them hopped into a 1960 GMC pickup truck and drove to a Naples gallery, where Wilkins saw sculptures that inspired him to become an artist. Still, art was merely a hobby until a chance meeting with artist Greg Biolchini in 1979 prompted Wilkins to quit the air-conditioning business and apply himself to sculpture full-time.

Biolchini  was gobsmacked as well.

was gobsmacked as well.

“I had a studio on the fourth floor of the Richards Building,” Biolchini recounts. “We had a sandwich sign on the sidewalk downstairs advertising for artists who wanted to share space.” At that time, the top floor of the Richards Building housed an ersatz artists’ colony, with dozens of local artists taking advantage of cheap rates and plenty of natural light.

“All of a sudden, this guy comes through the window and  without so much as introduction asks whether this woven wire tree he’d made was any good.”

without so much as introduction asks whether this woven wire tree he’d made was any good.”

Wilkins had seen the sign downstairs and climbed the fire escape in search of validation. He received it from Biolchini and Bill Turner, who was in also in the studio that day.

“The sculpture showed potential, but frankly we were more impressed by the enthusiasm, energy and confidence that he exuded. You just knew he was going to be successful if he just kept working on his craft.”

In fact, an inspirational quote immediately sprang to mind. “’Be bold and mighty forces  will come to your aid,’ I thought,” adds Biolchini, quoting Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and not for the last time.

will come to your aid,’ I thought,” adds Biolchini, quoting Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and not for the last time.

Those mighty forces came in 1983 when the City’s Beautification Advisory Board hired Wilkins to restore the City’s first two public artworks, the Tootie McGregor Fountain and Rachel at the Well.

At the direction of Olive Stout and Civic League, the Tootie McGregor Fountain had been installed during the summer of 1913 at Five Points, a roundabout formed by the confluence Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson Streets. Part horse trough and part memorial, the fountain was dedicated that August 17, on the first anniversary of Tootie McGregor’s death, and it presided over the roundabout until 1952 when it was dismantled to make way for the crossover to the Caloosahatchee Bridge. The pieces were hauled to the grounds of the Fort Myers Country Club, where they laid undisturbed

At the direction of Olive Stout and Civic League, the Tootie McGregor Fountain had been installed during the summer of 1913 at Five Points, a roundabout formed by the confluence Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson Streets. Part horse trough and part memorial, the fountain was dedicated that August 17, on the first anniversary of Tootie McGregor’s death, and it presided over the roundabout until 1952 when it was dismantled to make way for the crossover to the Caloosahatchee Bridge. The pieces were hauled to the grounds of the Fort Myers Country Club, where they laid undisturbed  and partially obscured by weeds for more than three decades.

and partially obscured by weeds for more than three decades.

Reassembling the fountain was a massive undertaking, but Wilkins was up to the task. He applied the skill set he had developed as a heating, ventilation and air-conditioning subcontractor to piece the pink granite and bronze Canary date palm back together,  adding a 40-foot-diameter receiving pool to add greater grandeur to the City’s only monument to Fort Myers’ greatest benefactor. Wilkins’ restoration has endured now for nearly four decades. Today the Tootie McGregor Fountain still graces the entrance to the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club.

adding a 40-foot-diameter receiving pool to add greater grandeur to the City’s only monument to Fort Myers’ greatest benefactor. Wilkins’ restoration has endured now for nearly four decades. Today the Tootie McGregor Fountain still graces the entrance to the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club.

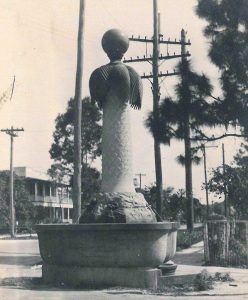

Situated at Edison Park on McGregor Boulevard, Rachel at the Well  had been commissioned by Uncommon Friends author James Newton as the entry piece for the residential development that Newton managed for the Snell Brothers in the mid-1920s. But by 1983, the Grecian maiden had fallen into woeful disrepair. The cast iron pipes that delivered water to the fountain had rusted and corroded, and the curves and features of the winsome maiden

had been commissioned by Uncommon Friends author James Newton as the entry piece for the residential development that Newton managed for the Snell Brothers in the mid-1920s. But by 1983, the Grecian maiden had fallen into woeful disrepair. The cast iron pipes that delivered water to the fountain had rusted and corroded, and the curves and features of the winsome maiden  were concealed beneath layers of white and green paint – the latter coming compliments of the Fort Myers High School senior class each year as part of their off-campus homecoming festivities.

were concealed beneath layers of white and green paint – the latter coming compliments of the Fort Myers High School senior class each year as part of their off-campus homecoming festivities.

By the time the Beautification Advisory Board commissioned Wilkins to restore her, Rachel had long since ceased functioning as a fountain. Wilkins replaced the old, nonfunctioning  cast iron pipes with PVC and added lighting to illuminate the maiden after dark. Then, like an archeologist at a dig on the Greek island of Knossos or Santorini, Wilkins painstakingly removed the 54 layers of alternating green and white paint that obscured Helmuth von Zengen’s delicate workmanship and innovative technique of applying a patented stone substitute in layers over a skeletal frame that obviated the

cast iron pipes with PVC and added lighting to illuminate the maiden after dark. Then, like an archeologist at a dig on the Greek island of Knossos or Santorini, Wilkins painstakingly removed the 54 layers of alternating green and white paint that obscured Helmuth von Zengen’s delicate workmanship and innovative technique of applying a patented stone substitute in layers over a skeletal frame that obviated the  need to chisel the figure from a single block of stone.

need to chisel the figure from a single block of stone.

After he completed the restoration, D.J. invited James Newton to the sculpture’s re-dedication. Newton graciously attended and shocked those who came to the ceremony when he divulged that the work’s true title is The Spirit of Fort Myers. Newton was deeply appreciative for the invitation, and the two became and remained friends until Newton’s death in 1999. So when Mayor Art Hammel asked Wilkins to design an artistic landmark for Centennial Park several years later, it was only natural for Wilkins to consult Newton about the scene he was envisioning of Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone camping on an island in the Everglades in 1914. But Wilkins went a step further. He asked  his friend if he could call the installation Uncommon Friends, which was the title of Newton’s groundbreaking book that chronicled the close bonds the “Vagabonds” shared with each other and their pals John Burroughs and Charles A. Lindbergh.

his friend if he could call the installation Uncommon Friends, which was the title of Newton’s groundbreaking book that chronicled the close bonds the “Vagabonds” shared with each other and their pals John Burroughs and Charles A. Lindbergh.

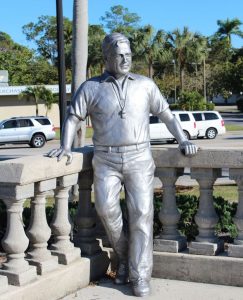

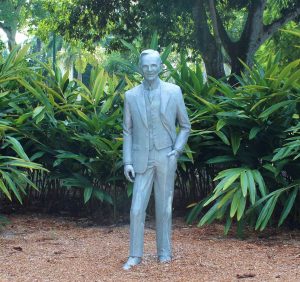

When he landed the commissions for Uncommon Friends and The Florida Panther: Countdown to Extinction in 1988, Wilkins’ first thought was to cast the figures in bronze. “But that would have more than quadrupled the cost of the $70,000 project to more than $325,000,” Wilkins recalled. That was way more than the Beautification Advisory Board could afford.  So D.J. took a page from Helmuth von Zengen’s playbook and devised a far less expensive alternative to bronze called “cold casting.”

So D.J. took a page from Helmuth von Zengen’s playbook and devised a far less expensive alternative to bronze called “cold casting.”

“I’ll claim partial credit for that,” laughs Greg Biolchini, who collaborated with Wilkins on several of his sculptural installations. “I’d read an article on cold casting in a trade journal, which I gave to Don.” A quick study, Wilkins embarked on a “self-directed journey of education,” teaching himself the process and making a handful of adaptations along the way.

“I’d read an article on cold casting in a trade journal, which I gave to Don.” A quick study, Wilkins embarked on a “self-directed journey of education,” teaching himself the process and making a handful of adaptations along the way.

Just as von  Zengen engrafted layers of stone substitute over a skeletal framework, Wilkins’ process began with entwining half to three-quarter inch hollow copper tubing and electrical wire to craft a stick figure that he then wrapped in Saran Wrap and filled with polyurethane, creating a “foam dude.” Like von Zengen, he then applied successive layers of plaster to make a cast or mold, which he removed with a reciprocating saw in nine sections.

Zengen engrafted layers of stone substitute over a skeletal framework, Wilkins’ process began with entwining half to three-quarter inch hollow copper tubing and electrical wire to craft a stick figure that he then wrapped in Saran Wrap and filled with polyurethane, creating a “foam dude.” Like von Zengen, he then applied successive layers of plaster to make a cast or mold, which he removed with a reciprocating saw in nine sections.  Into these molds, Wilkins then ladled a compound he mixed that consisted of ground metal (such as bronze or aluminum) and binder. Then came the hardest part of the entire process – piecing the hardened sections together without showing a seam and filling the void inside with highly-durable self-leveling Boston-whaler type foam or grout.

Into these molds, Wilkins then ladled a compound he mixed that consisted of ground metal (such as bronze or aluminum) and binder. Then came the hardest part of the entire process – piecing the hardened sections together without showing a seam and filling the void inside with highly-durable self-leveling Boston-whaler type foam or grout.  And just like that, Wilkins created a sculpture that gave the appearance of bronze or aluminum at a fraction of the cost!

And just like that, Wilkins created a sculpture that gave the appearance of bronze or aluminum at a fraction of the cost!

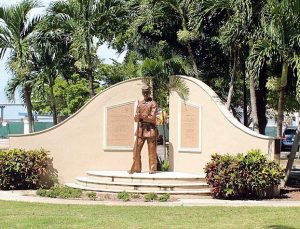

Over the ensuing dozen years, the Beautification Advisory Board commissioned Wilkins to create nearly two dozen 23 sculptures. In addition to Uncommon Friends and The Florida Panther, Wilkins’ resume includes The Great Turtle Chase (for  which his daughter, Elizabeth, served as muse), the USCT 2nd Regiment or Civil War Monument he nicknamed Clayton (because its fabrication required a ton of clay, the Wes Nott Statue on the campus of Lee Memorial Hospital, the balustrade and raised reliefs on the Manuel’s Branch Bridge south of Fort Myers High, and seven busts for the Harborside Event Center (now Caloosa Sound) that include Chief Billy Bowlegs, Francis A. Hendry, Tootie McGregor Terry, Paul L. Dunbar, Connie Mack, Thomas Edison and, of course, James D. Newton.

which his daughter, Elizabeth, served as muse), the USCT 2nd Regiment or Civil War Monument he nicknamed Clayton (because its fabrication required a ton of clay, the Wes Nott Statue on the campus of Lee Memorial Hospital, the balustrade and raised reliefs on the Manuel’s Branch Bridge south of Fort Myers High, and seven busts for the Harborside Event Center (now Caloosa Sound) that include Chief Billy Bowlegs, Francis A. Hendry, Tootie McGregor Terry, Paul L. Dunbar, Connie Mack, Thomas Edison and, of course, James D. Newton.

Wilkins, now in high demand, also cast a bust of Henry Ford and heroic size statues of Thomas Edison, Mina Edison and Henry Ford for  the Edison & Ford Winter Estates, as well as sculptures of Thomas Edison for both the Lee and Collier campuses of Edison State College.

the Edison & Ford Winter Estates, as well as sculptures of Thomas Edison for both the Lee and Collier campuses of Edison State College.

“Don was the right guy in the right place at the right time,” observes Ward Four Councilman Liston Bochette, a close family friend and longtime supporter of Wilkins and his work.

Like Bochette, Wilkins was proud of his sculptures. But he was  perhaps proudest of the restoration he completed of the replica of the Iwo Jima Memorial that Felix de Weldon made out of concrete for Julius and Leonard Rosen in 1964 for the Rose Garden tourist attraction the brothers created to help them sell Cape Coral homesites. Wilkins restored the mini-Iwo Jima Monument not once, but twice. The first time was in the early ‘80s. Wilkins characterized the effort as more of a salvage project than a restoration due to its condition at the time. Then in March of 2011, he spearheaded a second restoration to repair more than 250 feet of cracks that riddled the concrete due to its constant expansion and contraction caused by the temperature extremes and high humidity prevalent in Southwest Florida.

perhaps proudest of the restoration he completed of the replica of the Iwo Jima Memorial that Felix de Weldon made out of concrete for Julius and Leonard Rosen in 1964 for the Rose Garden tourist attraction the brothers created to help them sell Cape Coral homesites. Wilkins restored the mini-Iwo Jima Monument not once, but twice. The first time was in the early ‘80s. Wilkins characterized the effort as more of a salvage project than a restoration due to its condition at the time. Then in March of 2011, he spearheaded a second restoration to repair more than 250 feet of cracks that riddled the concrete due to its constant expansion and contraction caused by the temperature extremes and high humidity prevalent in Southwest Florida.

As it turned out, Wilkins’ experimental cold cast process suffered from the same infirmities.  Like the Iwo Jima Monument, a number of his sculptures began to experience cracks, fissures and spalling, particularly at the sites where he’d pieced together the various sections produced by the molds.

Like the Iwo Jima Monument, a number of his sculptures began to experience cracks, fissures and spalling, particularly at the sites where he’d pieced together the various sections produced by the molds.

For a time, the Beautification Advisory Board and the Parks and Beautification Department paid Wilkins to repair the recurring damage. But after the City created a  formal public art program in 2004 and assigned responsibility for the care of the City’s public art collection to a 9-member Public Art Committee, it appeared for a time that several of Wilkins’ high-maintenance pieces would be retired. Uncommon Friends, The Florida Panther and The Great Turtle Chase were all at risk of being “deaccessioned.” While the Committee debated their fate, their condition declined precipitously.

formal public art program in 2004 and assigned responsibility for the care of the City’s public art collection to a 9-member Public Art Committee, it appeared for a time that several of Wilkins’ high-maintenance pieces would be retired. Uncommon Friends, The Florida Panther and The Great Turtle Chase were all at risk of being “deaccessioned.” While the Committee debated their fate, their condition declined precipitously.

Like any good parent, D.J. became his babies’ chief advocate, even threatening legal action if the City failed to keep and properly maintain the legacy he’d created – not just for himself, but for all the good  people of Fort Myers.

people of Fort Myers.

While Wilkins’ sculptures are no longer at risk of being retired, the longevity is far from assured. The Public Art Committee has associated a highly-competent Miami-based conservation team to treat the inherent defects in Wilkins’ cold cast fabrication process, but the required maintenance is costly and public art program is chronically short of funds. But the City has recently launched a Sponsor-A-Sculpture program to attract individual and corporate partners who are willing to provide the funds needed  to ensure that Wilkins’ progeny remain sound and always look their best.

to ensure that Wilkins’ progeny remain sound and always look their best.

Today, many take Wilkins’ oeuvre or body of work for granted. That is unfortunate. Each tells a vital story about some aspect of our town’s early history. In the course of his work, Wilkins developed an abiding respect for the history of the town he adopted in 1975.

“People don’t have a sense of connection, a sense of history  here because so many folks are from elsewhere,” D.J. mused more than once.

here because so many folks are from elsewhere,” D.J. mused more than once.

Through his sculptural installations, Wilkins hoped to promote a greater appreciation for our unique heritage and he took satisfaction from the fact that the stories his artworks tell have now been captured and codified on a free phone app called Otocast – not only for residents, but for the tens of thousands of vacationers and cultural tourists who flock to Southwest Florida each winter.

The  Beautification Advisory Board granted Wilkins the rare honor and privilege of being able to use his craft not only to pay homage to our historical origins, but to advance our artistic and cultural heritage. And in so doing, Wilkins became a shining example of the contribution that public artists can make toward fostering civic pride, creating a positive first impression for visitors (thereby encouraging tourism), engendering a climate of creativity and elevating the quality of life for everyone

Beautification Advisory Board granted Wilkins the rare honor and privilege of being able to use his craft not only to pay homage to our historical origins, but to advance our artistic and cultural heritage. And in so doing, Wilkins became a shining example of the contribution that public artists can make toward fostering civic pride, creating a positive first impression for visitors (thereby encouraging tourism), engendering a climate of creativity and elevating the quality of life for everyone  who lives, works and visits the community.

who lives, works and visits the community.

In acknowledging Wilkins’ passing, many will be prompted to celebrate the individual works that he created during his tenure as the Sculptor of Fort Myers. “D.J. made Fort Myers even prettier than his mother found it,”observes Jeannie Wilkins, D.J.’s wife of 46 years.

But his impact was far greater and more pervasive. If he had not developed a more economical alternative to casting in bronze,  it is unlikely that the River District today contain any of its historical landmarks or that Fort Myers would boast the largest public art collection on the west coast of Florida south of Tampa.

it is unlikely that the River District today contain any of its historical landmarks or that Fort Myers would boast the largest public art collection on the west coast of Florida south of Tampa.

For all of these reasons and more, Don D.J. Wilkins joins the pantheon of pioneers who’ve made Fort Myers a slice of  paradise on Florida’s west coast. His work will continue to tell their stories to ensuing generations and challenge them to use their vision and creativity to make contributions of their own.

paradise on Florida’s west coast. His work will continue to tell their stories to ensuing generations and challenge them to use their vision and creativity to make contributions of their own.

October 12, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.