How the Everglades, Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie got so bad

A documentary about Southwest Florida’s ongoing environmental water crisis will open the Seventh Annual Fort Myers Film Festival on March 8. Titled Black Tide, the 50-minute film is the product of California-based Veriscope Productions and filmmaker Steven Johnson.

A documentary about Southwest Florida’s ongoing environmental water crisis will open the Seventh Annual Fort Myers Film Festival on March 8. Titled Black Tide, the 50-minute film is the product of California-based Veriscope Productions and filmmaker Steven Johnson.

For over fifty years, the combination of water mismanagement by the Army Corps. of Engineers and the political power of Big Sugar have created an environmental crisis in South Florida’s water. Black Tide is an investigative documentary that examines this crisis and looks for solutions to fix the ongoing environmental and economic devastation. But to appreciate the solutions offered  by the film, it’s important to understand just how the Everglades-Caloosahatchee-St. Lucie ecosystems got so screwed up in the first place. To provide the necessary backstory, local historical authors Robin Tuthill and Tom Hall (Female Pioneers of Fort Myers: Women Who Made a Difference in the City’s Development, © 2015, Editorial Rx Press) have provided

by the film, it’s important to understand just how the Everglades-Caloosahatchee-St. Lucie ecosystems got so screwed up in the first place. To provide the necessary backstory, local historical authors Robin Tuthill and Tom Hall (Female Pioneers of Fort Myers: Women Who Made a Difference in the City’s Development, © 2015, Editorial Rx Press) have provided  the following excerpt from a new book they are writing under the working title of Fort Myers Historic Hurricanes, due out later this year. It’s a bit lengthy, but if you have the time and the interest, give it a read:

the following excerpt from a new book they are writing under the working title of Fort Myers Historic Hurricanes, due out later this year. It’s a bit lengthy, but if you have the time and the interest, give it a read:

The Sad Saga of the Everglades

The Everglades, Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers and all the estuaries they feed are in real trouble today. While it’s not too late to repair the damage, it’s imperative to understand the confluence of political misjudgments, miscalculations and catastrophic events that caused this intricate natural ecological system to become so endangered. The first of these dates back 171 years

The Everglades, Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers and all the estuaries they feed are in real trouble today. While it’s not too late to repair the damage, it’s imperative to understand the confluence of political misjudgments, miscalculations and catastrophic events that caused this intricate natural ecological system to become so endangered. The first of these dates back 171 years  to 1845, when the very first Florida legislature dreamed of draining the Everglades in order to create land for sugar cane and rice plantations. The second traces its origin even further back in time than that to a Spaniard by the name of Pedro Menendez de Aviles who dreamed of finding a waterway across La Florida that connected the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic

to 1845, when the very first Florida legislature dreamed of draining the Everglades in order to create land for sugar cane and rice plantations. The second traces its origin even further back in time than that to a Spaniard by the name of Pedro Menendez de Aviles who dreamed of finding a waterway across La Florida that connected the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic  Ocean. But it wasn’t until the powerful hurricanes of 1926 and 1928 that both of these “dreams” (read, nightmares) were realized to our current chagrin and consternation.

Ocean. But it wasn’t until the powerful hurricanes of 1926 and 1928 that both of these “dreams” (read, nightmares) were realized to our current chagrin and consternation.

Before the Damage

From the Skybar atop The Firestone on Bay Street, the  Caloosahatchee appears as a wide expanse of slow-moving deep blue water, but from ground level, the river takes on a muddy brown cast as the silt, suspended solids and tannins swallow and obliterate the sun’s rays. But it wasn’t that way when Brevet Major Ridgely and two companies of artillery sailed up the river in 1850 to establish a fort on the slightly elevated hammock that now

Caloosahatchee appears as a wide expanse of slow-moving deep blue water, but from ground level, the river takes on a muddy brown cast as the silt, suspended solids and tannins swallow and obliterate the sun’s rays. But it wasn’t that way when Brevet Major Ridgely and two companies of artillery sailed up the river in 1850 to establish a fort on the slightly elevated hammock that now  supports downtown Fort Myers. So pristine was the river back then that the soldiers caught enough fish in a single day to sustain themselves for nearly a week, and the swimming pier and bathing pavilion became one of the fort’s most cherished and popular features in the years to follow.

supports downtown Fort Myers. So pristine was the river back then that the soldiers caught enough fish in a single day to sustain themselves for nearly a week, and the swimming pier and bathing pavilion became one of the fort’s most cherished and popular features in the years to follow.

The Major and his soldiers had been dispatched to build  the outpost they named Fort Myers for an ignominious purposes – to get rid of the Seminole Indians living in the Big Cypress and the swamp south of Lake Okeechobee so that the Everglades could be drained to provide farmland for plantation owners who wanted to use the rich muck beneath the water to grow sugar cane and rice.

the outpost they named Fort Myers for an ignominious purposes – to get rid of the Seminole Indians living in the Big Cypress and the swamp south of Lake Okeechobee so that the Everglades could be drained to provide farmland for plantation owners who wanted to use the rich muck beneath the water to grow sugar cane and rice.  You see, five years earlier, the first Florida Legislature had petitioned the United States Congress to “survey the Everglades with a view to their reclamation,” and in 1848, Buckingham Smith believed that draining the swamp could be achieved by simply connecting Lake Okeechobeee to the St. Lucie

You see, five years earlier, the first Florida Legislature had petitioned the United States Congress to “survey the Everglades with a view to their reclamation,” and in 1848, Buckingham Smith believed that draining the swamp could be achieved by simply connecting Lake Okeechobeee to the St. Lucie  and Caloosahatchee Rivers thereby letting the Glades empty into the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

and Caloosahatchee Rivers thereby letting the Glades empty into the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

But first, Chief Billy Bowlegs and his ragtag tribe of some 600 Seminoles (all that remained after two earlier wars) had to be dispossessed of their lands, and so the soldiers in Fort Myers instigated a war that  resulted in Bowlegs and 124 of his clan being deported to a reservation in Oklahoma in 1958, where the great chief and many of his tribesmen and women died just a year later in the latest small pox epidemic to ravage the native Americans living on the reservations in Oklahoma and Arkansas at that time.

resulted in Bowlegs and 124 of his clan being deported to a reservation in Oklahoma in 1958, where the great chief and many of his tribesmen and women died just a year later in the latest small pox epidemic to ravage the native Americans living on the reservations in Oklahoma and Arkansas at that time.

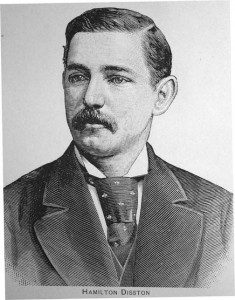

Hamilton Disston, The Man Who Promised to Drain the Everglades

The dream of draining the Everglades was put on hold during the Civil War and Reconstruction, but in 1881 a Philadelphia saw manufacturer by the name of Hamilton Disston convinced the State of Florida to sell him 4 million acres of land in the Everglades for $1 million in cash on the promise that he’d bring in great dredges to open a channel connecting the Caloosahatchee to Lake Okeechobee that would drain the Glades and produce millions of acres of rich, black muckland available for cultivation once and for all. The folks who lived in the fledgling cow town that had sprung up from the remnants of the old fort were delirious. They eagerly anticipated the arrival of the thousands of pioneers Disston

The dream of draining the Everglades was put on hold during the Civil War and Reconstruction, but in 1881 a Philadelphia saw manufacturer by the name of Hamilton Disston convinced the State of Florida to sell him 4 million acres of land in the Everglades for $1 million in cash on the promise that he’d bring in great dredges to open a channel connecting the Caloosahatchee to Lake Okeechobee that would drain the Glades and produce millions of acres of rich, black muckland available for cultivation once and for all. The folks who lived in the fledgling cow town that had sprung up from the remnants of the old fort were delirious. They eagerly anticipated the arrival of the thousands of pioneers Disston  proclaimed would settle the Glades and the land around the headwaters of the Caloosahatchee. Fort Myers was poised to become the gateway to a vast new empire.

proclaimed would settle the Glades and the land around the headwaters of the Caloosahatchee. Fort Myers was poised to become the gateway to a vast new empire.

“Disston undoubtedly had a special reason for being willing to go to the expense of draining the Everglades,” reports historian Karl Grismer in The  Story of Fort Myers. “That reason involved sugar …. [M]ost of the sugar plantations of the South which had been worked by slaves before the war were lying untilled. And production of sugar in Cuba had been disrupted by the Cuban insurrection of 1868 to 1878. The shortage of sugar was acute and it therefore demanded a premium price.”

Story of Fort Myers. “That reason involved sugar …. [M]ost of the sugar plantations of the South which had been worked by slaves before the war were lying untilled. And production of sugar in Cuba had been disrupted by the Cuban insurrection of 1868 to 1878. The shortage of sugar was acute and it therefore demanded a premium price.”

But Disston’s reclamation project failed and the sugar  cane he’d planted in the Glades as an experiment rotted in the ground. However, he had succeeded in dredging a canal between Lake Hicpochee and Lake Okeechobee, making it possible for shallow-draft boats from the Gulf, Punta Rassa and Fort Myers to access any point on the shores of the great inland lake. They were even able to reach Kissimmee far to the north.

cane he’d planted in the Glades as an experiment rotted in the ground. However, he had succeeded in dredging a canal between Lake Hicpochee and Lake Okeechobee, making it possible for shallow-draft boats from the Gulf, Punta Rassa and Fort Myers to access any point on the shores of the great inland lake. They were even able to reach Kissimmee far to the north.

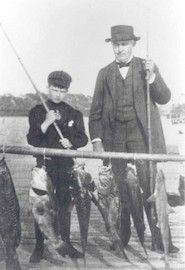

Damage to the river and its marine life as a result of the dredging was minimal, and the Gulf‘s waters were still pristine when Thomas Edison first came to town in 1885. One of the reasons Edison fell in love with the area was because of the river’s beauty, clarity and abundance of fish. In fact, Edison frequently fished from the pier he built to offload the lumber he imported from Maine to build Seminole Lodge.

Damage to the river and its marine life as a result of the dredging was minimal, and the Gulf‘s waters were still pristine when Thomas Edison first came to town in 1885. One of the reasons Edison fell in love with the area was because of the river’s beauty, clarity and abundance of fish. In fact, Edison frequently fished from the pier he built to offload the lumber he imported from Maine to build Seminole Lodge.

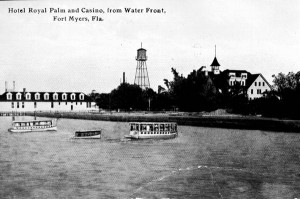

Tarpon fishing and the river’s scenic beauty were also what attracted Ambrose and Tootie McGregor to the fledgling town as well, but by the time Tootie McGregor Terry purchased the Royal Palm Hotel in 1907, the water’s edge had become littered with trash, garbage and decaying  hyacinths. Tootie convinced the city and adjoining property owners to resolve the problem by installing a seawall some 200 feet offshore and filling in the gap with dirt and sand. That done, the river again looked clean and clear, sunlight reflecting off the river’s white sandy bottom and

hyacinths. Tootie convinced the city and adjoining property owners to resolve the problem by installing a seawall some 200 feet offshore and filling in the gap with dirt and sand. That done, the river again looked clean and clear, sunlight reflecting off the river’s white sandy bottom and  stimulating the growth of the sea grasses in which fish and other marine life spawned and flourished. Back then, the river even teemed with Silver King during season, with anglers venturing daily into the river from the Royal Palm, Hotel Bradford and Fort Myers’ other downtown hostels. In fact, one of the most popular features of the Fort Myers Press was the tarpon report, which listed the names of

stimulating the growth of the sea grasses in which fish and other marine life spawned and flourished. Back then, the river even teemed with Silver King during season, with anglers venturing daily into the river from the Royal Palm, Hotel Bradford and Fort Myers’ other downtown hostels. In fact, one of the most popular features of the Fort Myers Press was the tarpon report, which listed the names of  permanent and winter residents who’d caught tarpon in the river that week together with the length and weight of their prizes and the time it took to boat their trophy.

permanent and winter residents who’d caught tarpon in the river that week together with the length and weight of their prizes and the time it took to boat their trophy.

Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward

But the dream of draining the Everglades did not die. In 1900, William Sherman Jennings became governor and reintroduced the idea of draining and developing the Everglades. Jennings’ successor, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, took that promise one step further, overseeing the dredging of canals to alter the flow of water in the river of grasses in an effort to build an “Empire of the Everglades” that would attract real estate dealers and settlors from around the world. Broward’s promises sparked another land boom. Rapidly growing Fort Lauderdale paid him tribute by naming Broward County after him (the town’s original plan had been to name it Everglades County). Land in the Everglades was being sold for $15 an acre–a month after Broward died in 1910.

But the dream of draining the Everglades did not die. In 1900, William Sherman Jennings became governor and reintroduced the idea of draining and developing the Everglades. Jennings’ successor, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, took that promise one step further, overseeing the dredging of canals to alter the flow of water in the river of grasses in an effort to build an “Empire of the Everglades” that would attract real estate dealers and settlors from around the world. Broward’s promises sparked another land boom. Rapidly growing Fort Lauderdale paid him tribute by naming Broward County after him (the town’s original plan had been to name it Everglades County). Land in the Everglades was being sold for $15 an acre–a month after Broward died in 1910.

The Cross-State Waterway and the River and Harbors Act of 1910

Something else momentous happened in 1910. On June 25 of that year, the River and Harbors Act became law. The legislation appropriated $121,000 (or roughly $3 million in today’s money) to deepen and widen the river channel from Punta Rassa to Fort Thompson in furtherance of a centuries-old dream of creating a cross-state waterway. Beginning in 1912, a makeshift waterway and drainage canals were established, but they quickly became choked with hyacinths and were abandoned and forgotten with the advent of World War I. But after the war, a record-breaking real estate boom took place in Florida. During the Great Boom, people flocked to Fort Myers, and farming communities popped up in Moore Haven (“Little Chicago), Belle Glade (“Muck City”) and Clewiston. But their efforts to cultivate sugar cane and other crops was impeded by the poor drainage and recurring flooding. But that changed as the result of two great hurricanes that swept through South Florida in the latter part of the Roaring ‘20s.

The Great Hurricane of September 17, 1928

The hurricanes took place on September 18, 1926 and September 17, 1928. The latter was a Category 5 storm, and its high winds and heavy rains caused Lake Okeechobee to breach the modest levees that had been built to protect Belle Glades and Clewiston from flooding. Between 2,500 and 3,000 people drowned.

The Herbert Hoover Dike

After the 1928 storm, the Florida Legislature created the Okeechobee Flood Control District and authorized it to cooperate with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in installing an appropriate flood control infrastructure. After a personal inspection of the area by President Herbert Hoover, the Corps came up with a plan called the Central and South Florida (C&SF) Project which provided for the construction of floodway channels, control gates, and major levees along Lake Okeechobee’s shores. A long-term system was designed for the purpose of flood control and water conservation. In furtherance of the plan, a larger system of levees was built around the lake.

In the 1960s, the dike was expanded to completely enclose the lake but for a gap at Fisheating Creek, where the dike turns inland and parallels the stream on both sides for several miles, leaving Fisheating Creek as the only remaining free-flowing tributary of Lake Okeechobee.

While the Herbert Hoover Dike did not serve to drain the Everglades as the Florida Legislature and Hamilton Disston once dreamed, it nonetheless accomplished the goal of reclaiming the swamp for sugar cane and agricultural purposes. Averaging 30 feet (9 meters) in height, the Herbert Hoover Dike effectively cuts off the flow of lake water south into the Everglades and Florida Bay.

It is important to realize that this is a design choice. The Okeechobee Flood Control District and the Army Corps of Engineers could have designed flood control structures that would have evacuated lake water during storms and periods of heavy rainfall south into the Everglades as nature intended. But instead, they opted to relieve pressure on the dike by discharging excess water through a system of locks into the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers, a choice made possible by W.P. Franklin and his determination to realize Pedro Menendez de Aviles’ dream of establishing a cross-state waterway.

W.P. Franklin and the Cross-State Waterway

Fort Myers hardware magnate, hotelier and local politician W.P. Franklin seized upon the opportunity presented by the Central and South Florida Project to resurrect the cross-state waterway. As a result of his lobbying and political influence, the St. Lucie canal was dug from Lake Okeechobee east to Stuart, a new and larger canal was dug from the head of the Caloosahatchee to the lake, and the channel in the Caloosahatchee was deepened to seven feet from Fort Myers all the way upriver to Fort Thompson. The waterway’s opening was celebrated for two whole days, with Franklin leading a delegation from Fort Myers in a 40-boat watercade from Stuart to Fort Myers. But it was this cross-state waterway that created the predicate for the ecological damage and destruction that the Everglades, the Caloosahatchee, the St. Lucie and their estuaries are experiencing today.

Enter Big Sugar

While work on the cross-state waterway and Herbert Hoover Dike was still in the discussion and planning stages, Southern Sugar Corporation began operations in the tiny town of Clewiston on the southern tip of Lake Okeechobee. The operation was not profitable, and Southern Sugar sold its land and assets in 1931 to Charles Stewart Mott, who was the well-heeled Vice President of General Motors at the time. He worked with the Army Corps of Engineers to drain the acreage he’d purchased for purposes of planting sugar cane, and he developed strains of sugar cane that could be successfully grown in Florida’s wet, humid and subtropical climate. Mott’s new company was called U.S. Sugar, but notwithstanding the massive infusion of Mott’s capital, the company’s operations remained small and not very profitable.

From early in its history, U.S. Sugar was the beneficiary of a complex system of federal tariffs, quotas and subsidies, but the company’s competitive advantage in the U.S. and world market was finally secured with the United States’ embargo on Cuba in 1959. But with the Cuban Revolution also came competition in the form of Alphonso Fanjul’s Florida Crysals/Domino Sugar. Both U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals worked in concert with the U.S. Corps of Army Engineers and Okeechobee Flood Control District to perfect the network of dikes, canals, irrigation and drainage systems to create the perfect environment for sugar cane and other crops in the Everglades Agricultural Area, as originally envisioned by Buckingham Smith, Florida’s first legislature and Hamilton Disston in the 1800s. And now that the dream of growing sugar cane and other crops on lands reclaimed from the Everglades has been realized, Big Sugar zealously protects their holdings through political influence in the form of campaign contributions, lobbying, marketing and publicity.

It is to Big Sugar’s advantage to pump water into their fields during periods of drought and to drain their fields into Lake Okeechobee during the rainy season. The water dumped into the lake contains high levels of fertilizer, pesticides and other chemicals which mingle with those carried by stormwater runoff from farmlands and cattle ranches to the north of the lake. None of these commercial interests filter, cleanse or purify either the runoff or the lake, shifting that burden instead to the state and federal government. And for its part, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is a willing partner.

U.S. Army Corps’ Complicity

Today, a giant network of more than 100 water control structures and 1,400 miles of canals control water levels across the former Everglades ecosystem. These canals have impeded the natural water flow on which the system depends. There’s too much water when the system needs to be dry, and not enough when it needs to be wet. Florida Bay is dying for lack of fresh water, while Barnes Sound’s productive food web is drowning .

The water that is used to irrigate Big Sugar’s fields during periods of drought is diverted from the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers. The reduced flow allows salt water intrusion into freshwater environments, unnaturally changing the salinity in these ecological systems. The excess water that is released into the rivers during periods of high rainfall causes freshwater plumes in the Gulf of Mexico (some as large as 15 miles) and fouls both rivers, their estuaries and the Gulf with high levels of nutrients (fertilizers and manure) as well as chemicals (pesticides, herbicides etc.) that kill marine life and reduce fertility. The suspended solids prevent photosynthesis, which kills sea grasses and other vegetation needed for spawning as well. The system’s hydrology bears no semblance to that which existed when Brevet Major Ridgely arrived in 1850 and raised the U.S. flag over Fort Myers, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reduces and increases the flow of contaminated water into the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers regardless of the consequences in order to protect the Herbert Hoover Dike and the commercial interests of Big Sugar and the agricultural and ranching interests north of the lake.

Caloosahatchee 7th Most Endangered River in United States

By 2006, the situation had become so dire that American Rivers named the Caloosahatchee the 7th most endangered river in the nation. “The scale of the damage to water quality, aquatic habitat, fish and wildlife … [is] a national level ecological tragedy,” said American Rivers, noting that intense algae blooms have severely depleted oxygen levels in the Caloosahatchee, resulting in the decimation of the river’s commercial seafood and sports fishing species. Instrumental in American River’s condemnation of the river’s health was the fact that between 2000 and 2006, there were 570 days when the blue-green algae blooms were so bad that public health officials were compelled to issue orders prohibiting swimming in the river. That situation persists today.

And the damage extends far beyond the Caloosahatchee. Five National Wildlife Refuges depend on the Caloosahatchee River for water, including J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Caloosahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, Island Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Matlacha Pass National Wildlife Refuge, and Pine Island National Wildlife Refuge. Many are showing signs of impaired ecosystems as a result of the polluted waters of the Caloosahatchee. Hundreds of square miles of the Gulf of Mexico are also adversely impacted by the freshwater plume emanating from the Caloosahatchee River.

Fixing the Problem is a Choice

The U.S. Corps of Army Engineers acknowledges today that the Herbert Hoover Dike is in dire need of upgrade and repair. Florida International University’s International Hurricane Research Center lists Lake Okeechobee as the No. 2 threat of catastrophic flooding from a natural disaster, behind only New Orleans.

“The current condition of Herbert Hoover Dike poses a grave and imminent danger to the people and the environment of South Florida. In this, we join many other investigators, from grassroots engineers to eminent specialists, who for 20 years have warned that Herbert Hoover Dike needs to be fixed,” reads a South Florida Water Management District report from 2006. “We can add only that it needs to be fixed now, and it needs to be fixed right. We firmly believe that the region’s future depends on it.”

However, rather than re-think the decision made in 1929 to prevent the flow of water south, the Corps seeks instead to buttress the structural integrity of the dike by improving 32 water control structures which they say are the most prone to seepage and leaks even though this will cost more than the Army Corps’ entire budget of $4.7 billion. “We want to strengthen it to the point where it will handle major events,” said John Campbell, with the Army Corps, while touring a construction site near Pahokee. “When it gets up to 18 to 20 feet, it’s a concern.”

But there is another way. Rather than continuing to use Lake Okeechobee as a reservoir, more than 200 scientists, ecologists and other researchers recommend building reservoirs, marshes and flow paths in the Everglades Agricultural Area south of the lake to receive, filter, cleanse and purify excess lake water before re-directing it south into the Everglades, where it can eventually flow into Florida Bay as it did before the Seminole nation was kicked out of the Big Cypress and the Florida Legislature, Hamilton Disston, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, W.P. Franklin, President Herbert Hoover and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers interfered with Mother Nature. Of course, this strategy will require the State of Florida to purchase enough land from Big Sugar to accommodate the necessary structures, but our public health and safety, our leisure & hospitality industry and the severely damaged ecosystems of the lake, rivers, estuaries, Gulf and the Everglades itself demand this action. It’s not a question of science. It’s a matter of politics. And the question we must now ask is whether we have the vision and political will to reverse 170+ years of bad, uninformed and improvident decisions.

If you are interested in purchasing a copy of the Fort Myers Historic Hurricanes, please email tom@artswfl.com to be placed on a pre-publication list.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.