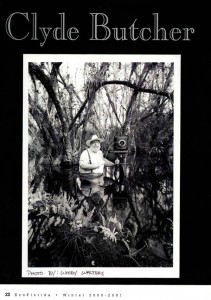

A word or two about Everglades fine art photographer Clyde Butcher

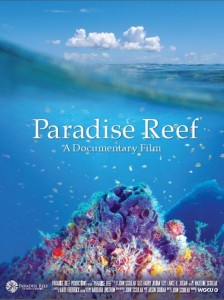

One of the films being screened at this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival taking place March 8-12 is Paradise Reef, a 56-minute documentary directed, filmed and edited by John Scoular. Three years in the making, the documentary follows a visionary’s quest to secure BP disaster funds, rally community support, and deploy 18,000 tons of concrete to create 36 artificial reefs along Florida’s Paradise Coast. Through captivating aerial footage and in-depth interviews, the film also shows the symbiotic relationship between, and the natural beauty of, the Everglades, the Ten Thousand Islands, the Gulf of Mexico and Collier County, Florida. And who better to help provide narration and interviews for a film like this than

One of the films being screened at this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival taking place March 8-12 is Paradise Reef, a 56-minute documentary directed, filmed and edited by John Scoular. Three years in the making, the documentary follows a visionary’s quest to secure BP disaster funds, rally community support, and deploy 18,000 tons of concrete to create 36 artificial reefs along Florida’s Paradise Coast. Through captivating aerial footage and in-depth interviews, the film also shows the symbiotic relationship between, and the natural beauty of, the Everglades, the Ten Thousand Islands, the Gulf of Mexico and Collier County, Florida. And who better to help provide narration and interviews for a film like this than  iconic Everglades fine art photographer Clyde Butcher?

iconic Everglades fine art photographer Clyde Butcher?

Although he will always be associated with the Florida Everglades, Clyde Butcher is deeply committed to recording and protecting precious landscapes throughout the world. Because of the majestic beauty, boldness and depth of all his  subjects, Butcher’s photographs have earned him recognition as the foremost landscape photographic artist in America today.

subjects, Butcher’s photographs have earned him recognition as the foremost landscape photographic artist in America today.

Among his numerous awards and accolades is membership in the Artist Hall of Fame, the highest honor that the State of Florida can award to a private citizen. Butcher is also a recipient of the State of Florida’s Heartland Community Service Award in recognition of the role he has played in  educating the people of Florida about the beauty of their state. In a similar vein, the Sierra Club has given him the Ansel Adams Conservation Award, which is given to photographers who show excellence in photography and have contributed to the public’s awareness of the environment. Butcher has also received the North American Nature Photography Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, International University’s 2005 Humanitarian of the Year Award, and the 2011 Distinguished Artists Award from the Florida House in Washington D.C.

educating the people of Florida about the beauty of their state. In a similar vein, the Sierra Club has given him the Ansel Adams Conservation Award, which is given to photographers who show excellence in photography and have contributed to the public’s awareness of the environment. Butcher has also received the North American Nature Photography Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, International University’s 2005 Humanitarian of the Year Award, and the 2011 Distinguished Artists Award from the Florida House in Washington D.C.

The beauty and importance of his photography has resulted in museum exhibits throughout the United States, an exhibit at the  National Gallery of Art in Prague celebrating the new millennium, and a request by the United Nations to photograph the mountains of Cuba to commemorate The Year of the Mountains.

National Gallery of Art in Prague celebrating the new millennium, and a request by the United Nations to photograph the mountains of Cuba to commemorate The Year of the Mountains.

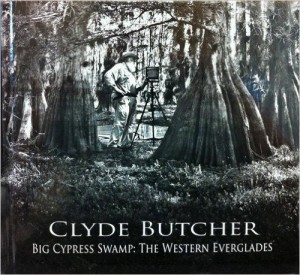

Collections of Butcher’s work can be seen in his books, which include:

- Portfolio I, Florida Landscapes;

- 1995 Limited Edition Collection;

- Visions for the Next Millennium;

Nature’s Places of Spiritual Sanctuary;

Nature’s Places of Spiritual Sanctuary;- Florida Landscape;

- Living Waters – Florida’s Aquatic Preserves;

- Cuba – The Natural Beauty;

- Apalachicola River – An American Treasure;

- Seeing the Light: Wilderness and Salvation, a Photographer’s Tale;

- America the Beautiful, a table top collection of

his work from across the United States;

his work from across the United States; - Big Cypress Swamp – The Western Everglades, which features images from the Big Cypress Swamp where he and wife Niki made their home for 16 years; and

- Portfolio II – Florida, a collection of images from Florida.

Clyde had either hosted or been the featured guest in six Public Broadcasting programs, including an award-winning half-hour documentary on Clyde titled Visions of Florida, Big Cypress Preserve: Jewel of the Everglades, Living Waters – Aquatic Preserves of Florida, which Clyde hosted, and Apalachicola River – An American Treasure, in which Clyde was the featured guest. As these award-winning documentaries underscore, the Everglades possesses particular significance to

Clyde had either hosted or been the featured guest in six Public Broadcasting programs, including an award-winning half-hour documentary on Clyde titled Visions of Florida, Big Cypress Preserve: Jewel of the Everglades, Living Waters – Aquatic Preserves of Florida, which Clyde hosted, and Apalachicola River – An American Treasure, in which Clyde was the featured guest. As these award-winning documentaries underscore, the Everglades possesses particular significance to  Butcher. The Everglades have changed much in the last 100 years. Originally comprising more than 3 million acres, early settlers drained the land for agriculture and diverted the natural flow of water to rivers like the Caloosahatchee. In the aftermath of the destructive hurricanes of 1926 and 1928, miles of canals, dikes and dams were installed to protect the land around Lake Okeechobee from

Butcher. The Everglades have changed much in the last 100 years. Originally comprising more than 3 million acres, early settlers drained the land for agriculture and diverted the natural flow of water to rivers like the Caloosahatchee. In the aftermath of the destructive hurricanes of 1926 and 1928, miles of canals, dikes and dams were installed to protect the land around Lake Okeechobee from  flooding. Urban areas and their highway connections have further encroached on the watershed and siphoned its water. But through the years, Butcher’s photography has demonstrated that the Florida of times past is still there, even if its harder to find and reach.

flooding. Urban areas and their highway connections have further encroached on the watershed and siphoned its water. But through the years, Butcher’s photography has demonstrated that the Florida of times past is still there, even if its harder to find and reach.

Other projects include work for Florida’s “Save Our Rivers” program, the South Florida Water Management District, the Department of Environmental Protection, Divisions of State Lands, the Bureau of Submerged Lands and Preserves, Everglades National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, the Audubon Society, The Nature Conservancy, River Keepers and the Wilderness Society.

His Photography

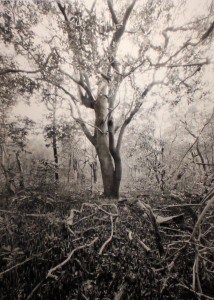

Clyde Butcher’s black-and-white landscape photography is known for evoking a feeling that America’s vistas are timeless even as development approaches. His images of the Florida Everglades, national parks and Cuba are celebrated for the tiny details that emerge from each print – the texture of bark, the veins of a leaf, the ripples within the shadow of a cloud reflected in a body of water. But

Clyde Butcher’s black-and-white landscape photography is known for evoking a feeling that America’s vistas are timeless even as development approaches. His images of the Florida Everglades, national parks and Cuba are celebrated for the tiny details that emerge from each print – the texture of bark, the veins of a leaf, the ripples within the shadow of a cloud reflected in a body of water. But  beyond the aesthetic merits of his work, what distinguishes Clyde Butcher’s photography from that of other landscape photographers is the incredibly detailed mural-sized prints he produces.

beyond the aesthetic merits of his work, what distinguishes Clyde Butcher’s photography from that of other landscape photographers is the incredibly detailed mural-sized prints he produces.

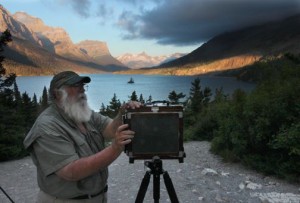

By carefully matching view camera format size to the subject matter being photographed, Butcher is able to make prints measuring up to 5 x 9 feet that  enable the viewer to experience the breadth and scope of the landscape in the same way that Butcher sees it in the field. Toward the end, Butcher captures his images using a combination of 8 x 10 inch, 11 x 14 inch, and 12 x 20 inch view cameras. These large format cameras enable him to express the elaborate detail and textures that distinguish the intricacy of the landscape.

enable the viewer to experience the breadth and scope of the landscape in the same way that Butcher sees it in the field. Toward the end, Butcher captures his images using a combination of 8 x 10 inch, 11 x 14 inch, and 12 x 20 inch view cameras. These large format cameras enable him to express the elaborate detail and textures that distinguish the intricacy of the landscape.

To capture the images he covets, Butcher hikes off the beaten path with large format cameras, lenses and unexposed film in tow to get just the right shot. He has been known to stand in chest-deep water for hours, waiting until the light, clouds and composition of each dramatic composition come together. “I try to use the largest film possible for the particular subject I’m planning to photograph,” Clyde explains. “So if I have a huge, broad

To capture the images he covets, Butcher hikes off the beaten path with large format cameras, lenses and unexposed film in tow to get just the right shot. He has been known to stand in chest-deep water for hours, waiting until the light, clouds and composition of each dramatic composition come together. “I try to use the largest film possible for the particular subject I’m planning to photograph,” Clyde explains. “So if I have a huge, broad  landscape, I use the 12 x 20 inch view camera. If I am photographing something like the Ghost Orchid, I use a 4 x 5 inch view camera.”

landscape, I use the 12 x 20 inch view camera. If I am photographing something like the Ghost Orchid, I use a 4 x 5 inch view camera.”

Clyde began making large prints as long ago as 1968, but over the last twenty or so years, he has refined and perfected his technique of producing mural-sized prints. “The first time I did a huge print, I had to wash it in a swimming pool,” laughs Butcher. “Eventually, I moved into a large space, where I built big sinks to handle the large sizes of my prints.”

“I want people to view my work up close,” muses Clyde about his desire to create large scale prints. “When you’re in nature, you’re scanning from the log to that tree to the bird to the water, and your mind puts the images together to create the feeling of the scene. When you view my large prints, your mind does the same thing because you cannot see all the images all at once. And sharpness is the key

“I want people to view my work up close,” muses Clyde about his desire to create large scale prints. “When you’re in nature, you’re scanning from the log to that tree to the bird to the water, and your mind puts the images together to create the feeling of the scene. When you view my large prints, your mind does the same thing because you cannot see all the images all at once. And sharpness is the key  to it. Your eyes – your brain – wants things to be clear and sharp. All of that makes the viewer relate to my images in a way that is similar to the peace felt when being out in nature. I want my images to create a positive emotion in people, with the hope that they carry that emotion out into their lives to make the world a better place in which to live.”

to it. Your eyes – your brain – wants things to be clear and sharp. All of that makes the viewer relate to my images in a way that is similar to the peace felt when being out in nature. I want my images to create a positive emotion in people, with the hope that they carry that emotion out into their lives to make the world a better place in which to live.”

Within the last couple of years, Butcher has begun to substitute lightweight, compact point-and-shoot digital cameras for the heavy, clunky view cameras and wide angle lenses of the past. However, his emphasis remains unchanged. He still looks for angles and details that will draw his viewers into each image he takes. “When I see a scene that stirs my soul, I photograph it. Since I have been

Within the last couple of years, Butcher has begun to substitute lightweight, compact point-and-shoot digital cameras for the heavy, clunky view cameras and wide angle lenses of the past. However, his emphasis remains unchanged. He still looks for angles and details that will draw his viewers into each image he takes. “When I see a scene that stirs my soul, I photograph it. Since I have been  photographing the landscape for over fifty years, I instinctively see texture, value, scale and composition, which create a satisfying photograph to me personally. I’m always glad when it’s well-received by others.”

photographing the landscape for over fifty years, I instinctively see texture, value, scale and composition, which create a satisfying photograph to me personally. I’m always glad when it’s well-received by others.”

While, in the end, Butcher’s black-and-white photographs explore his own uniquely personal relationship with nature, he does hope that his images inspire feelings of stewardship toward the environment. The wilderness has always been a place where he’s found sanctuary and serenity. It was there he sought refuge after his 17-year-old son, Ted, was killed by a drunk driver. “The mysterious spiritual experience of being close to nature helped restore my soul. It was during that time,  I discovered the intimate beauty of the environment. My experience reinforced my sense of dedication to use my art form of photography as an inspiration for others to work together to save nature’s places of spiritual sanctuary for future generations.”

I discovered the intimate beauty of the environment. My experience reinforced my sense of dedication to use my art form of photography as an inspiration for others to work together to save nature’s places of spiritual sanctuary for future generations.”

February 26, 2017.

- Overview of the 7th Annual Fort Myers Film Festival

- Why you should see ‘Paradise Reef’

- Meet ‘Paradise Reef’ writer and director John Scoular

Meet ‘Paradise Reef’ cinematographer and commentator Andy Brandy Casagrande IV

Meet ‘Paradise Reef’ cinematographer and commentator Andy Brandy Casagrande IV- Meet ‘Paradise Reef’ underwater still photographer Emma Casagrande

- A look back at John Scoular documentary ‘Marcus Jansen: Examine & Report’

- Lake O discharge documentary, ‘Black Tide,’ to open Fort Myers Film Festival

- Meet ‘Black Tide’ writer, director and producer Steven Johnson

- Read what ‘Black Tide’ filmmaker

Steven Johnson has to say about his documentary

Steven Johnson has to say about his documentary - How the Everglades, Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie got so bad

- Why you should see ‘Bubbles’

- How ‘Bubbles’ got made

- Meet ‘Bubbles’ screenwriter and maniacal clown Cesar Aguilera

- Why you should see ‘The Radical Jew’

- ‘Radical Jew’ awards and accolades

- Why you should see ‘The Stairs’

- Why the filmmakers made ‘The Stairs’

- Why you should see ‘Three Wishes’ at this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival

- Meet ‘Three Wishes’ writer, director and producer Curtis Collins

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.