Tootie McGregor Fountain

The Tootie McGregor Fountain was Fort Myers’ first public art piece. It was installed at the intersection of Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson Streets during the summer of 1913 and later moved to the Fort Myers Country Club in the 1950s to

The Tootie McGregor Fountain was Fort Myers’ first public art piece. It was installed at the intersection of Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson Streets during the summer of 1913 and later moved to the Fort Myers Country Club in the 1950s to  make way for the approach to the Caloosahatchee Bridge.

make way for the approach to the Caloosahatchee Bridge.

The fountain features a palm tree rising from a rocky base that emerges from a smooth bowl that originally served as a horse trough. The base, trunk and polished orb at the top were carved  from pink granite quarried in northern Georgia. The palm fronds are made of bronze, as are the five venomous snakes that once served as water spouts. Two of the snakes are water moccasins (also known as cottonmouths); two are eastern diamondback rattlesnakes; the fifth is a coral snake.

from pink granite quarried in northern Georgia. The palm fronds are made of bronze, as are the five venomous snakes that once served as water spouts. Two of the snakes are water moccasins (also known as cottonmouths); two are eastern diamondback rattlesnakes; the fifth is a coral snake.

No  information has been found that identifies the species of palm featured by the fountain. However, based upon the feather-like, dark green fronds at the top and the pattern of unique diamond-shaped leaf scars covering the stout brown trunk, it appears that it is a Canary Date Palm or Phoenix dactylifera. If so, it is a curious choice since Tootie McGregor Terry was closely associated with the Royal

information has been found that identifies the species of palm featured by the fountain. However, based upon the feather-like, dark green fronds at the top and the pattern of unique diamond-shaped leaf scars covering the stout brown trunk, it appears that it is a Canary Date Palm or Phoenix dactylifera. If so, it is a curious choice since Tootie McGregor Terry was closely associated with the Royal  Palm Hotel, which she restored to prominence after acquiring it in 1907.

Palm Hotel, which she restored to prominence after acquiring it in 1907.

Similarly, no information has been located that identifies the fountain’s sculptor, the significance of the smooth orb located at the top of the tree or why Dr. Marshall or the sculptor chose to adorn the rocky base with venomous snakes indigenous to Florida.

All totaled, the fountain weighs 24 tons and cost $5,000 in 1913 (which would equate with roughly $250,000 in today’s money).

A fter being stored in pieces for more than three decades, it was reassembled by North Fort Myers sculptor Don (“D.J.”) Wilkins in 1983. Incident to his commission from the Fort Myers Beautification Advisory Board, Wilkins set the fountain in the center of a 40-foot-diameter reflection pool and piped the water through several bronze bullfrogs set at the pool’s perimeter. Nearly a decade later, he removed the shaft inside the trunk of the palm tree so that water cascaded into the base and receiving pool from the top of the tree.

fter being stored in pieces for more than three decades, it was reassembled by North Fort Myers sculptor Don (“D.J.”) Wilkins in 1983. Incident to his commission from the Fort Myers Beautification Advisory Board, Wilkins set the fountain in the center of a 40-foot-diameter reflection pool and piped the water through several bronze bullfrogs set at the pool’s perimeter. Nearly a decade later, he removed the shaft inside the trunk of the palm tree so that water cascaded into the base and receiving pool from the top of the tree.

History of the Fountain

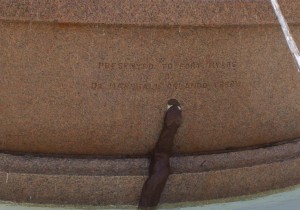

Dr. Marshall Orlando Terry proposed the fountain as a memorial to his wife, Tootie, in a letter to the Fort Myers City Council dated December 6, 1912.

Dr. Marshall Orlando Terry proposed the fountain as a memorial to his wife, Tootie, in a letter to the Fort Myers City Council dated December 6, 1912.

In consideration for the fountain, the city agreed to light the fountain “with not less than five incandescent electric lights of 32 candlepower each,” provide water “in sufficient volume for carrying full capacity of its fountain,” and place the fountain at “some prominent point” within the city” to be approved by Dr. Terry and the city council.

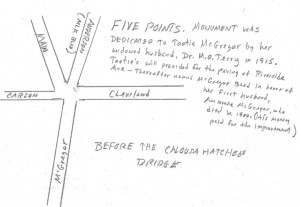

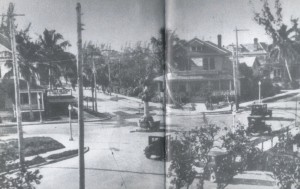

Under the direction of its president, Olive Stout, the Civic League c hose Five Points as the location for the fountain. A broad intersection formed by the confluence of Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson streets, Stout and the League felt that the site provided the space and visibility that the fountain deserved. Fort Myers Press, January 23, 1913. The location also paid homage

hose Five Points as the location for the fountain. A broad intersection formed by the confluence of Cleveland Avenue, Anderson Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), McGregor Boulevard, Main and Carson streets, Stout and the League felt that the site provided the space and visibility that the fountain deserved. Fort Myers Press, January 23, 1913. The location also paid homage  to the fact that McGregor Boulevard was paved and renamed in honor of her first husband, Ambrose McGregor, as a result of Tootie’s offer to pay the costs of improving Riverside Drive from Whisky

to the fact that McGregor Boulevard was paved and renamed in honor of her first husband, Ambrose McGregor, as a result of Tootie’s offer to pay the costs of improving Riverside Drive from Whisky  Creek to Punta Rassa if the city and county would improve the road from Whisky Creek to Monroe Street.

Creek to Punta Rassa if the city and county would improve the road from Whisky Creek to Monroe Street.

The fountain was completed sometime during the summer of 1913. The Fort Myers Press reported in its July 10, 1913 edition that “nearly all the material for the McGregor memorial fountain is in the  ound and ready to be set in place. Workmen who have been sent here by the designers of this beautiful granite shaft and fountain have placed the heavier pieces in position for erection, which work will be undertaken in the next few days.” About a week later, the newspaper indicated that work was progressing well, but nothing of the fountain’s completion or dedication (if any) made i

ound and ready to be set in place. Workmen who have been sent here by the designers of this beautiful granite shaft and fountain have placed the heavier pieces in position for erection, which work will be undertaken in the next few days.” About a week later, the newspaper indicated that work was progressing well, but nothing of the fountain’s completion or dedication (if any) made i t into the publication. However, the fountain was clearly finished by August 17, 1913 because there appeared in the Press a brief note indicating that “the Terry memorial fountain was draped by a beautiful bouquet of ferns and roses all day Sunday, it being the first anniversary of Mrs. T. McGregor Terry’s” death. Fort Myers Press, Aug. 19, 1913.

t into the publication. However, the fountain was clearly finished by August 17, 1913 because there appeared in the Press a brief note indicating that “the Terry memorial fountain was draped by a beautiful bouquet of ferns and roses all day Sunday, it being the first anniversary of Mrs. T. McGregor Terry’s” death. Fort Myers Press, Aug. 19, 1913.

Long-time resident James Butler relates that in addition to a horse trough, the fountain served as a turn-about in the Five Points intersection and a drinking fountain for dogs. The water bowl for dogs is still visible, and can be found to the left of the dedication at the base of the fountain.

Long-time resident James Butler relates that in addition to a horse trough, the fountain served as a turn-about in the Five Points intersection and a drinking fountain for dogs. The water bowl for dogs is still visible, and can be found to the left of the dedication at the base of the fountain.

While the fountain was still standing in 1948, historian Karl H. Grismer reports in The Story of Fort Myers that it was bereft of  its “lights and the heads of snakes from which water used to gush.” (At page 207.) Four years later (in 1952), the fountain was dismantled to make way for the crossover to the Caloosahatchee Bridge. The palm tree in the center was moved to the Fort Myers Country Club, roughly 250 feet from its present location. At least three of the five snakes were placed in storage.

its “lights and the heads of snakes from which water used to gush.” (At page 207.) Four years later (in 1952), the fountain was dismantled to make way for the crossover to the Caloosahatchee Bridge. The palm tree in the center was moved to the Fort Myers Country Club, roughly 250 feet from its present location. At least three of the five snakes were placed in storage.

The fountain was ultimately reassembled by local sculptor D.J. Wilkins between 1983 and 1984 at the request of the Fort Myers Beautification Advisory Board. Incident to the fountain’s restoration, Wilkins added a 40-foot diameter receiving pool and replaced the bronze copperhead  snake at the base of the palm trunk. But rather than piping water through the original snake fountain heads and risking their theft or further deterioration, Wilkins directed jets of water through bronze bullfrogs sitting on upturned leaves. “In 1992, we removed the shaft,” says Wilkins, “and piped the water to the top and over the fronds.”

snake at the base of the palm trunk. But rather than piping water through the original snake fountain heads and risking their theft or further deterioration, Wilkins directed jets of water through bronze bullfrogs sitting on upturned leaves. “In 1992, we removed the shaft,” says Wilkins, “and piped the water to the top and over the fronds.”

Since its restoration, the Tootie McGregor Fountain has graced the front of the Edison Restaurant in the clubhouse of the Fort Myers Country Club, with the city once more providing lighting, water and a prominent location within Fort Myers. However, the view of the fountain was marred in 2014 when a railed ramp was added to the Edison Restaurant for ADA purposes.

The Woman for Whom the Fountain is Named

T ootie McGregor ne’ Jerusha H. Barber was a woman’s whose real life is the stuff of a Charlotte Bronte or Nathaniel Hawthorne romance novel. Born in 1843 to a middle class Cleveland judge by the name of Epaphras Barber, she fell in love during high school with Marshall Terry, a struggling medical student who was so poor he didn’t dare ask for her hand in marriage. Jerusha’s love went unrequited as Terry set off to seek his fortune, serving in the Spanish-American War and eventually becoming the surgeon general of the state of New York.

ootie McGregor ne’ Jerusha H. Barber was a woman’s whose real life is the stuff of a Charlotte Bronte or Nathaniel Hawthorne romance novel. Born in 1843 to a middle class Cleveland judge by the name of Epaphras Barber, she fell in love during high school with Marshall Terry, a struggling medical student who was so poor he didn’t dare ask for her hand in marriage. Jerusha’s love went unrequited as Terry set off to seek his fortune, serving in the Spanish-American War and eventually becoming the surgeon general of the state of New York.

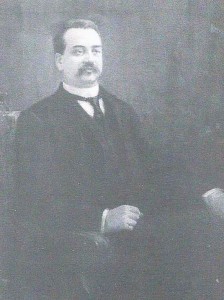

Jerusha didn’t wait. She met, was wooed by and married a young salesman by the name of Ambrose McGregor. Ambrose combined ambition with hard w ork as he set about making a name for himself. His young bride helped, pinching pennies and sewing Ambrose’s clothes in the newlyweds’ rented apartment above a local grocery store. Ambrose succeeded in spectacular fashion, eventually becoming the president of an oil company by the name of Standard Oil.

ork as he set about making a name for himself. His young bride helped, pinching pennies and sewing Ambrose’s clothes in the newlyweds’ rented apartment above a local grocery store. Ambrose succeeded in spectacular fashion, eventually becoming the president of an oil company by the name of Standard Oil.

“Tootie” and Ambrose had but one child, a son they named Bradford. The boy was sickly, and his doctors advised the couple to winter in Florida where the temperate climate would have a beneficial effect on Bradford’s health. The couple could have wintered anywhere, but they were lured to Fort Myers’ by the region’s excellent tarpon fishing.

In 1892, they purchased the west half of the Seminole Lodge for $4,000 from Thomas Edison’s estranged phonograph company business partner Ezra T. Gilliland. Over the next eight years, Ambrose bought more than 30 local properties, invested in citrus, and bankrolled a young real estate developer by the name of Harvie

In 1892, they purchased the west half of the Seminole Lodge for $4,000 from Thomas Edison’s estranged phonograph company business partner Ezra T. Gilliland. Over the next eight years, Ambrose bought more than 30 local properties, invested in citrus, and bankrolled a young real estate developer by the name of Harvie  Heitman in the construction of a couple of downtown buildings, including Fort Myers’ first brick building, a two-story structure on the site of Heitman’s first store at the northwest corner of First and Jackson streets. Regrettably, the oil tycoon died of cancer on October 28, 1900 at the age of just 58. However, he left Tootie a very wealthy widow, with an estate estimated to be worth more than $16 million, which made her one of the 10 wealthiest people in the entire United States.

Heitman in the construction of a couple of downtown buildings, including Fort Myers’ first brick building, a two-story structure on the site of Heitman’s first store at the northwest corner of First and Jackson streets. Regrettably, the oil tycoon died of cancer on October 28, 1900 at the age of just 58. However, he left Tootie a very wealthy widow, with an estate estimated to be worth more than $16 million, which made her one of the 10 wealthiest people in the entire United States.

In September of 1902, Bradford married his high school sweetheart, Florence Quintard. He died just two days later.

W ith both her husband and son now deceased, Tootie could have packed up and moved back to Cleveland, or anywhere in the world in which she chose to live. But she remained faithful to Fort Myers. Further, she decided to take an active role in the development of the city. She is remembered most today for her efforts to improve Lee County’s roadways. As mentioned above, Tootie famously

ith both her husband and son now deceased, Tootie could have packed up and moved back to Cleveland, or anywhere in the world in which she chose to live. But she remained faithful to Fort Myers. Further, she decided to take an active role in the development of the city. She is remembered most today for her efforts to improve Lee County’s roadways. As mentioned above, Tootie famously  made an offer that the city and Lee County couldn’t refuse. If they agreed to pave Riverside Drive from Whiskey Creek to downtown Fort Myers, she would pay to have the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa paved. She agreed to use whatever materials the City and County chose, and put in all necessary bridges and culverts along the way. She even offered to pay $500

made an offer that the city and Lee County couldn’t refuse. If they agreed to pave Riverside Drive from Whiskey Creek to downtown Fort Myers, she would pay to have the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa paved. She agreed to use whatever materials the City and County chose, and put in all necessary bridges and culverts along the way. She even offered to pay $500  annually to maintain the new road for five years after construction was finished. Unfortunately, Tootie did not live long enough to see the roadway started or completed, but second husband Dr. Marshall Terry honored his wife’s wishes, even purchasing a barge and a number of three-ton trucks for purposes of delivering and hauling the shell necessary of construction of the paved roadway. Fort Myers Press, Sept. 18, 1913.

annually to maintain the new road for five years after construction was finished. Unfortunately, Tootie did not live long enough to see the roadway started or completed, but second husband Dr. Marshall Terry honored his wife’s wishes, even purchasing a barge and a number of three-ton trucks for purposes of delivering and hauling the shell necessary of construction of the paved roadway. Fort Myers Press, Sept. 18, 1913.

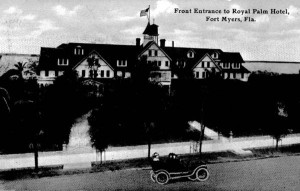

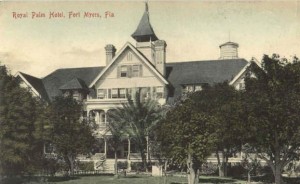

But Tootie’s contributions to the city’s development and  promotion to the outside world far outstripped the mere paving of old Riverside Drive. She almost single-handedly established Fort Myers as a tourist destination characterized by top-flight, world-renowned hotels. In 1904, Tootie collaborated with Ambrose’s partner, Harvie Heitman, on the construction of a hotel at the corner of First and Hendry

promotion to the outside world far outstripped the mere paving of old Riverside Drive. She almost single-handedly established Fort Myers as a tourist destination characterized by top-flight, world-renowned hotels. In 1904, Tootie collaborated with Ambrose’s partner, Harvie Heitman, on the construction of a hotel at the corner of First and Hendry  streets to be named “The Bradford” in honor of her son. Three years later, she rescued the city’s financially-troubled landmark, the Royal Palm Hotel, doubling its size and inducing property owners from Monroe east to Billy’s Creek to construct a concrete seawall 200 feet of the existing bank of the Caloosahatchee and fill

streets to be named “The Bradford” in honor of her son. Three years later, she rescued the city’s financially-troubled landmark, the Royal Palm Hotel, doubling its size and inducing property owners from Monroe east to Billy’s Creek to construct a concrete seawall 200 feet of the existing bank of the Caloosahatchee and fill  in the gap with sand and shell dredged up from the river bottom. She later purchased the Riverside Hotel, as well. Her trio of hostelries attracted numerous celebrities and millionaires to Fort Myers. Many followed her lead and that of Thomas Edison, making Fort Myers the site of their own winter

in the gap with sand and shell dredged up from the river bottom. She later purchased the Riverside Hotel, as well. Her trio of hostelries attracted numerous celebrities and millionaires to Fort Myers. Many followed her lead and that of Thomas Edison, making Fort Myers the site of their own winter  homes.

homes.

But she did not forget her native Cleveland. In Pioneer Families of Cleveland, author Gertrude Wickham writes that Tootie “was a very bright, attractive woman and was much use to the world.” She partnered with her sister, Sophia Barber McCrosky, to found one of that city’s first private nursing homes. The sisters conceived it as a place for “gentlewomen who could no longer care for themselves.” Also named for Ambrose, the the A.M. McGregor Home was incorporated in 1904, opened in 1908 with 25 residents, and still serves Ohio’s elderly today.

A fter Bradford’s untimely demise, Marshall Terry re-entered the picture. He had never married and was still carrying a torch for Tootie. He fanned the smoldering embers of their decades-old romance into a torrid fire, and induced Tootie to marry him on December 12, 1905. The following year, the couple donated 40 acres of land to the city for use as a golf course. However, because of the poor sandy roads that served it, the country club never took off and some two decades later, the land

fter Bradford’s untimely demise, Marshall Terry re-entered the picture. He had never married and was still carrying a torch for Tootie. He fanned the smoldering embers of their decades-old romance into a torrid fire, and induced Tootie to marry him on December 12, 1905. The following year, the couple donated 40 acres of land to the city for use as a golf course. However, because of the poor sandy roads that served it, the country club never took off and some two decades later, the land  was converted into a spring training facility for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians and Fort Myers Palms. Today, this tract bears the name of Terry Park, and it played a pivotal role to bringing Major League Baseball spring training to the City of Fort Myers.

was converted into a spring training facility for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians and Fort Myers Palms. Today, this tract bears the name of Terry Park, and it played a pivotal role to bringing Major League Baseball spring training to the City of Fort Myers.

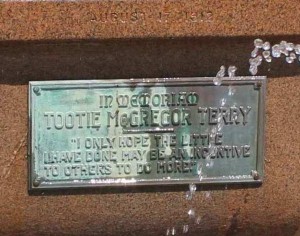

Tootie and Marshall enjoyed six years together. She died on August 17, 1912 at her summer home at Mamaroneck-on-the-Hudson in New York. Following Tootie’s death, Dr. Marshall assumed responsibility for completing the road work that his wife  had undertaken and decided to donate a fountain to the city in honor of his late wife, inscribing it with her own words, “I only hope the little I have done may be an incentive to others to do more.”

had undertaken and decided to donate a fountain to the city in honor of his late wife, inscribing it with her own words, “I only hope the little I have done may be an incentive to others to do more.”

You can read more about Tootie McGregor Terry and her impressive accomplishments in Tuthill and Hall, Female Pioneers of Fort Myers: Women Who Made a Difference in the City’s Development (Editorial Rx Press, 2015), pp. 59-66.

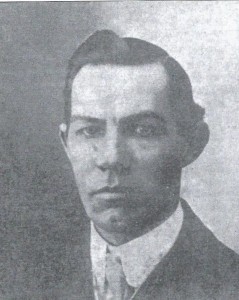

A Note about Dr. Marshall Orlando Terry

Marshall Orlando Terry was born in Wateryliet, New York to William Henry a nd Sarah Burke Terry. He went to high school in Ashtabula, Ohio before entering the Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College, from which he graduated in 1872. It was during this time that he met and first fell in love with Jerusha H. Barber who later became known as Tootie McGregor. But being too poor to ask for her hand in marriage, he went off to New York to find fortune and fame.

nd Sarah Burke Terry. He went to high school in Ashtabula, Ohio before entering the Cleveland Homeopathic Hospital College, from which he graduated in 1872. It was during this time that he met and first fell in love with Jerusha H. Barber who later became known as Tootie McGregor. But being too poor to ask for her hand in marriage, he went off to New York to find fortune and fame.

On March 18, 1880, Terry was appointed a major in the fourth brigade of the New York National Guard. That appointment positioned him to be named on January 1, 1895 as Surgeon-General of the State of New York. He was re-appointed by Governor Black on  January 1, 1897, thus serving four years.

January 1, 1897, thus serving four years.

President Grover Cleveland appointed Dr. Terry as United States Pension Surgeon for the Utica district, where he served as president of the medical board. He was offered the position of chief surgeon of division during the Spanish-American war by President William McKinley, but declined owing to his duties as surgeon  general.

general.

Rising to the rank of Brigadier General, Terry was a member of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States and president of the Association of Military Surgeons of the National Guard and of the Naval Militia of the State of New York. He was instrumental in substituting a new medical and surgical outfit  for the national guard, and the “Terry” stretcher, named by Adjutant General McAlpin for its originality, has a mechanically adjustable pillow.

for the national guard, and the “Terry” stretcher, named by Adjutant General McAlpin for its originality, has a mechanically adjustable pillow.

He came to Fort Myers in the early 1900s, where he re-met and married Fort Myers’ civic leader and benefactress Tootie McGregor in 1905. After her death in 1912, he completed construction of a 50-foot wide paved road from  Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa that his wife had promised to construct shortly before her death. On December 6, 1912, Terry proposed installing a fountain at a prominent location in Fort Myers as a memorial to his wife.

Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa that his wife had promised to construct shortly before her death. On December 6, 1912, Terry proposed installing a fountain at a prominent location in Fort Myers as a memorial to his wife.  The Tootie McGregor Fountain was completed sometime around the first anniversary of her death on August 17, 1913. The fountain was Fort Myers’ first public artwork.

The Tootie McGregor Fountain was completed sometime around the first anniversary of her death on August 17, 1913. The fountain was Fort Myers’ first public artwork.

Location and Measurements.

- T

he Tootie McGregor Fountain sits in front of the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club clubhouse.

he Tootie McGregor Fountain sits in front of the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club clubhouse. - Its street address is 3583 McGregor Boulevard, Fort Myers.

- Its coordinates are longitude 26d 36′ 35.787″ N and latitude 81d 53′ 5.607″ W.

- No information is provided at this time regarding the fountain’s height, width and depth of the base, shaft or

orb.

orb. - However, according to sculptor DJ Wilkins, the granite used in the base, shaft and orb weight a whopping 24 tons.

Fun Facts.

- To understand the depth of Tootie McGregor Terry’s frustration with Fort Myers’ system of “roads,” it is helpful to know that when she and Ambrose first came to town in 1892, not one street was paved or even graded.

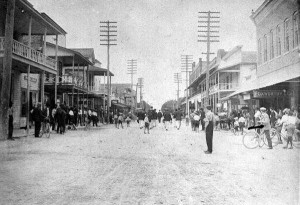

- First Street (which was called Front Street at the time) was nothing more than a sandy, weed-grown open space that meandered between two irregular rows of unpainted, cheaply constructed wood frame general stores, saloons, livery stables, blacksmith shops and houses.

- The only sidewalk was a shell walkway that William H. Towles and James E. Hendry laid in April of 1886 in front of their store at First and Jackson. At the time, the Fort Myers Press stated that “our streets and sidewalks at present are a disgrace to the town.”

- Towles and Hendry also installed an oil-burning streetlamp outside their store when it became clear in June of 1887 that Thomas Edison wasn’t going to carry through on his promise to “light Fort Myers.” But the townspeople still had to use lanterns whenever they ventured outside after dark.

- There were but three bridges in Fort Myers, one over Whiskey Creek, a second spanning Billy’s Creek and a wooden foot bridge that crossed Manuel’s Branch. None spanned the Caloosahatchee River itself.

- And the roads leading into and out of town were virtually non-existent, consisting of two sets of deep ruts created by oxcart wagon wheels that cut through clutching sand and clinging mud. People referred to these trails as “Wish to God” roadways because regardless of which set of ruts the traveler chose, he always “wished to God” he had taken the other set.

- The county commissioners addressed the problem in late 1900 by purchasing shell for 15 cents a barrel and then hiring laborers to fill in the oxcart tracks from Billy’s Creek to Buckingham. Two feet wide and six inches deep, the new “surface” did not make the road passable during rainy season and over time, the shell disintegrated and disappeared in the mud and sand. To compensate, logs were laid crosswise over the ruts, giving rise to the nickname “corduroy roads.”

- But the shell inspired the city council in 1901 to propose a bond issue to improve the streets, but when the proposal was defeated at the polls, the city councilmen borrowed the money necessary to purchase 20,000 barrels of shell on their own personal notes. To get the shell needed, Calusa Indian mounds up and down the river were levelled, but this only provided enough shell to create a 15-foot wide strip down the center of First Street from Billy’s Creek to Monroe.

- “This narrow strip was so ‘marvelously smooth’ and such an improvement over the old sandy waste,” writes local historian Karl H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers (p. 168), “that the property owners immediately demanded that the entire street be covered. So did the property owners elsewhere in the business section.”

- But nothing happened to the roads in town for another 12 years!

- Meanwhile, the movement to get concrete sidewalks for the business section was launched in the summer of 1904 by William H. Towles, Harvie Heitman and George F. Ireland. They were finally laid in 1906 by Manuel S. Gonzalez, who left his mark “M.S.G. – 1906 in the concrete.

- But notwithstanding these “improvements,” Fort Myers was still a cow town. Literally. Due to the influence of the town’s powerful cattle barons, cows were still allowed to roam freely through the streets until September 4, 1908, when an ordinance was finally adopted mandating that cattle and milk cows alike be penned up. From New York, Dr. Terry wrote: “I am delighted beyond expression,” echoing the sentiment felt by hundreds of other Fort Myers residents and visitors.

- But several more months would follow before the ordinance was extended to hogs, and outside of town, hogs were permitted to wander freely for several more years, much to the vexation of Tootie and her husband, Dr. Marshall O. Terry.

- And this was the state of affairs when Tootie proposed in February of 1912 to pave the 20-mile stretch of Riverside Drive from Whisky Creek to Punta Rassa if Fort Myers and Lee County would pave from Whisky Creek to Monroe Street.

- Unfortunately, Tootie did not live long enough to see the roadwork started.

- She did not even live long enough to see Fort Myers approve a $47,000 bond issue to “hard surface” the roads in town in 1913; rejecting advocates who lobbied for brick or concrete, the city opted for shell-asphalt, which was completed in the late summer of 1915. Although nice and smooth when originally installed, they didn’t remain that way for very long as summer rains soon began wreaking havoc with them.

- Tootie and Dr. Terry were ahead of their time. They not only understood that a paved McGregor Boulevard would open all the invaluable land it abutted to development, but that good roads leading into and out of town were needed if the town was to develop as it should. Because the latter were not provided until the 1920s, Fort Myers almost missed out on the growth experienced by other Florida cities during the real estate boom that began toward the end of World War I.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Wonderful article and photos. Thanks you so much.

Now as an employee of the McGregor Foundation in Cleveland, these are very interesting articles about Tootie, Ambrose, and the McGregor legacy!