Immediacy, intimacy, bareknuckle honesty make ‘Anna in the Tropics’ must see

Lab Theater is celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month with a production of playwright Nilo Cruz’s period piece play Anna in the Tropics. Forget that Cruz won a Pulitzer Prize for the play. Or that Lab’s production features an all-Latino cast. Go see this play because it is truly transformative. It possesses immediacy, intimacy and bareknuckle honesty – rare attributes whether you’re talking literature, film or theater.

Lab Theater is celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month with a production of playwright Nilo Cruz’s period piece play Anna in the Tropics. Forget that Cruz won a Pulitzer Prize for the play. Or that Lab’s production features an all-Latino cast. Go see this play because it is truly transformative. It possesses immediacy, intimacy and bareknuckle honesty – rare attributes whether you’re talking literature, film or theater.

At the center of this psychodrama is a love triangle between a woman  named Conchita, her husband of many years, Palomo, and a relative stranger who reads to them from Tolstoy’s epic novel, Anna Karenina. It is 1929. In Ybor City. And like men of that time and place, Palomo has taken a mistress. He satisfies his need for intimacy with her, leaving poor, hapless Conchita to endure an unfulfilling, loveless marriage.

named Conchita, her husband of many years, Palomo, and a relative stranger who reads to them from Tolstoy’s epic novel, Anna Karenina. It is 1929. In Ybor City. And like men of that time and place, Palomo has taken a mistress. He satisfies his need for intimacy with her, leaving poor, hapless Conchita to endure an unfulfilling, loveless marriage.

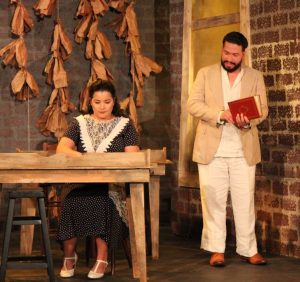

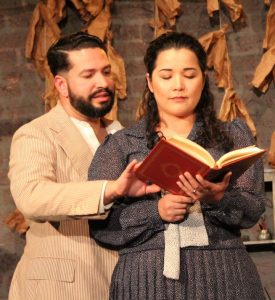

But then she hears the story of Anna Karenina from the lips of Juan Julian, a handsome young lector hired by her father’s cigar factory. Conchita and Palomo work there as rollers, as do her parents, younger sister and other members of the family. And much like Anna Karenina in the novel, Conchita decides that if her husband can find happiness in adultery, she can too. So she begins an affair with Juan Julian, doing little to conceal it and even flouting the relationship in Palomo’s face.

Ah, but the  key question here, as in Anna Karenina, is whether Conchita is exercising free will or merely acting out a predetermined fate.

key question here, as in Anna Karenina, is whether Conchita is exercising free will or merely acting out a predetermined fate.

By contrast, Conchita’s father, Santiago, leads a life of wanton excess. He drinks too much. His gambling borders on addiction. If he didn’t have bad judgment, he’d have no judgment at all. Then he, too, falls under the influence of Anna Karenina. And like Anna Karenina and his daughter, Conchita, he also chooses to make changes in his life. But in his case, he decides that instead of wagering on the local cock fights, he’ll bet his money and his resources on his cigar factory and, derivatively, all the family  members who depend on him for their livelihood.

members who depend on him for their livelihood.

Clearly, Cruz is expressing in both of these instance the transformative power of literature. All forms of art – from literature to film to theater – have the power to touch the heart, expand consciousness and inspire change. But on stage at  The Lab, what jumps out at the audience is the immediacy with which the characters make these choices and the honesty with which they communicate their thoughts and feelings with one another. Instead of using the story as a welcome distraction from the limiting circumstances that govern the quality of their lives, Conchita, Palomo and Santiago use the plot and characters Tolstoy has created to think about their own situations, relationships and how their is going.

The Lab, what jumps out at the audience is the immediacy with which the characters make these choices and the honesty with which they communicate their thoughts and feelings with one another. Instead of using the story as a welcome distraction from the limiting circumstances that govern the quality of their lives, Conchita, Palomo and Santiago use the plot and characters Tolstoy has created to think about their own situations, relationships and how their is going.

Some people  purport to take inventory of their lives on momentous birthdays (30th, 40th and so on) or New Year’s Day, sleepwalking through life like automatons the other 363 or 364 days of the year. But Nilo Cruz postulates that a great novel like Anna Karenina – or a play or a movie – can provide a springboard for introspection and self-analysis any time at all.

purport to take inventory of their lives on momentous birthdays (30th, 40th and so on) or New Year’s Day, sleepwalking through life like automatons the other 363 or 364 days of the year. But Nilo Cruz postulates that a great novel like Anna Karenina – or a play or a movie – can provide a springboard for introspection and self-analysis any time at all.

The characters in Anna in the Tropics do just that. More, they communicate the affect that the novel has and is having on their thoughts, emotions and actions, and they do it with an eloquence rare in any genre.

The characters in Anna in the Tropics do just that. More, they communicate the affect that the novel has and is having on their thoughts, emotions and actions, and they do it with an eloquence rare in any genre.

Nowhere is this more in evidence than the intimate discussion that ensues between Conchita and Paloma. In what is unquestionably the play’s most poignant scene, they talk candidly about their respective affairs. With prompting from Palomo, Conchita even divulges how Juan Julian touches her, what he does to her body during lovemaking, and how it makes her feel.

It’s hard  to imagine many other couples speaking so openly under similar circumstances. By the time a relationship has devolved to the point where one or both spouses have taken other lovers, neither is interested in or capable of communicating meaningfully with the other at all. So what role models could Carmen Rivera, who plays Conchita, and Miguel Cintron, who plays Palomo, have possibly used as a template for their performances? It’s truly a tribute to the direction supplied by Annette Trossbach and testament to Rivera and Cintron’s acting prowess and sensitivity that they are able so aptly portray

to imagine many other couples speaking so openly under similar circumstances. By the time a relationship has devolved to the point where one or both spouses have taken other lovers, neither is interested in or capable of communicating meaningfully with the other at all. So what role models could Carmen Rivera, who plays Conchita, and Miguel Cintron, who plays Palomo, have possibly used as a template for their performances? It’s truly a tribute to the direction supplied by Annette Trossbach and testament to Rivera and Cintron’s acting prowess and sensitivity that they are able so aptly portray  behavior and conversation that so few of us have ever seen or heard.

behavior and conversation that so few of us have ever seen or heard.

Without a doubt, Rivera is the star of this play, and delivers such a refined and nuanced performance that it will linger in your mind, if not your heart, for some time to come. Cintron has previously turned heads in The Gun Show (for Theatre Conspiracy) and An Act of God (for Lab). But Gun Show was a one-man play; Act of God filled with monologues, soliloquys and riffs. His portrayal of Palomo required interactions between and among other characters that underscores he is an equally  accomplished dramatic actor with as bright a future as he cares to pursue. That’s great news for all of us who may see him in future productions.

accomplished dramatic actor with as bright a future as he cares to pursue. That’s great news for all of us who may see him in future productions.

David Pimentel is equally superb in the role of the lector and Conchita’s paramour, Juan Julian. He brings a subtle, slow-burning sexual chemistry to the role that threatens to ignite and burn the house down whenever he and Carmen Rivera happen to be alone on stage. He’s sure to appeal to the women in the audience , especially with his slow delivery and sensuously-accented diction as he reads from Tolstoy and interacts with the other characters in the play.

Come to think of it,  he’s the perfect spokesman for Nilo Cruz’s brand of prose, in which every word has the appeal and indulgence of a tantalizing Brian Roland hors d’oeuvre.

he’s the perfect spokesman for Nilo Cruz’s brand of prose, in which every word has the appeal and indulgence of a tantalizing Brian Roland hors d’oeuvre.

All the acting is exceptional. Isaac Osin (Santiago) and Grace Delvalle-Hernandez (Santiago’s wife Ofelia) are wonderful, and Ronaldo Chico Guido (as Cheche) and Chloe Tsai (as Conchita’s younger sister, Marela) steal many of the scenes in which they appear. [Follow the links provided below for more in-depth treatment of their characters and performances.]  Chalk it up to the talent pool of Hispanic actors here in Southwest Florida or Trossbach’s gift for direction. You’re right either way.

Chalk it up to the talent pool of Hispanic actors here in Southwest Florida or Trossbach’s gift for direction. You’re right either way.

Ah, but if you’re familiar with the story of Anna Karenina, you’re probably wondering whether the competing love triangles work out as disastrously for Conchita as they did for Anna in the novel. While the ending comes with a twist that Cruz amply foreshadows, the denouement is not the point of the play.  Unlike the novel within the story, Anna in the Tropics is more optimistic about our ability to actually affect our circumstances and change the course of our lives. We are not, in Cruz’s estimation, puppets of fate, bound to play roles with predetermined outcomes.

Unlike the novel within the story, Anna in the Tropics is more optimistic about our ability to actually affect our circumstances and change the course of our lives. We are not, in Cruz’s estimation, puppets of fate, bound to play roles with predetermined outcomes.

If only we could all learn to communicate openly and candidly with the people we love and who are presumptively importance to us. If only we could embrace lives of immediacy, living in the moment rather than fretting over past transgressions and missed opportunities  or dreaming of a better future, with no map or plans on how to get there. If only we could choose to be the stars of our own lives rather than living vicariously through the Kardashians or TV or movie stars.

or dreaming of a better future, with no map or plans on how to get there. If only we could choose to be the stars of our own lives rather than living vicariously through the Kardashians or TV or movie stars.

This is what Nilo Cruz encourages us to aspire to through the story and characters of Anna in the Tropics.

RELATED POSTS.

- Lab celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month with ‘Anna in the Tropics’

- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ playwright Nilo Cruz

- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ director Annette Trossbach

- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ actor Miguel Cintron

For ‘Anna in the Tropics,’ Rinaldo Chico Guido gets deadly serious

For ‘Anna in the Tropics,’ Rinaldo Chico Guido gets deadly serious- ‘Heathers’ Chloe Tsai is dreamy as ‘Anna in the Tropics’ Marela Alcalar

- Havana-born Isaac Osin brings depth of understanding to character of Santiago Alcalar

- ‘Anna in the Tropics’ play dates, times and ticket info

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.