Miguel Cintron and David Pimentel sound off on romance, love and Latino men

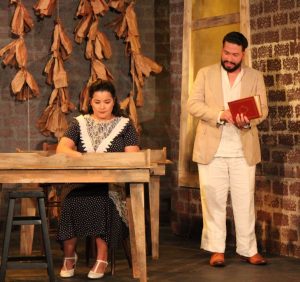

Tonight marks the start of the final four performances of Anna in the Tropics. While there are a number of intriguing subplots and side themes, the storyline revolves around a couple by the names of Palomo and Conchita whose marriage has gone stale. But the stultifying status quo is suddenly upset when Conchita begins an affair with a rakish young man by the name of Juan Julian who is hired by the Ybor City cigar factory where they both work as rollers.

Tonight marks the start of the final four performances of Anna in the Tropics. While there are a number of intriguing subplots and side themes, the storyline revolves around a couple by the names of Palomo and Conchita whose marriage has gone stale. But the stultifying status quo is suddenly upset when Conchita begins an affair with a rakish young man by the name of Juan Julian who is hired by the Ybor City cigar factory where they both work as rollers.

Of course, this is an egregious  oversimplification of the state of the couple’s relationship. “Palomo is that traditional, stereotypical Cuban guy who takes his wife for granted … and he did what some men of that era [the play is set in the summer of 1929] did, he took a mistress, a lover,” notes Miguel Cintron of his character during an interview with his on-stage rival

oversimplification of the state of the couple’s relationship. “Palomo is that traditional, stereotypical Cuban guy who takes his wife for granted … and he did what some men of that era [the play is set in the summer of 1929] did, he took a mistress, a lover,” notes Miguel Cintron of his character during an interview with his on-stage rival  David Pimentel prior to final dress rehearsal for the play a couple of weeks ago.

David Pimentel prior to final dress rehearsal for the play a couple of weeks ago.

“I stress the word ‘stereotypical’ because that’s not what all Cuban men or Hispanic men are like,” Cintron quickly adds, setting the record straight. “But it’s what men apparently did back then and Palomo felt he was entitled to do the same.”

That  prerogative did not extend to women in Cuban culture as the Roaring Twenties gave way to the woes of the Great Depression. But then Conchita is introduced by Juan Julian to Tolstoy and the story of Anna Karenina.

prerogative did not extend to women in Cuban culture as the Roaring Twenties gave way to the woes of the Great Depression. But then Conchita is introduced by Juan Julian to Tolstoy and the story of Anna Karenina.

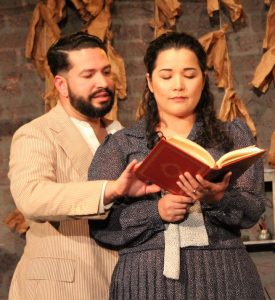

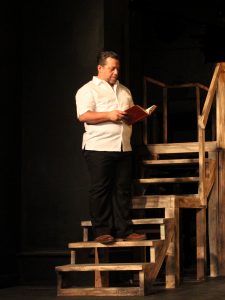

Julian is a lector. Lectors were hired by Cuban cigar manufacturers prior to the Great Depression to read from newspapers, magazines and books to the workers in order to entertain, educate and distract them from the monotonous and boring task of  rolling cigars by hand. As the story opens, Juan Julian has arrived by boat from Havana to replace the company’s previous lector. And the very first novel he decides to share with Palomo, Conchita and the rest of the workers in the factory is Anna Karenina.

rolling cigars by hand. As the story opens, Juan Julian has arrived by boat from Havana to replace the company’s previous lector. And the very first novel he decides to share with Palomo, Conchita and the rest of the workers in the factory is Anna Karenina.

It proved to be a fateful choice because the story of Anna Karenina and her husband Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin runs parallel to that of Conchita and Palomo. Like Palomo, Alexei is cowed by social convention, shows little tenderness to his wife, and takes her for granted. And like Palomo, Alexei has a mistress  as well.

as well.

But then Anna Karenina begins an affair with a dashing military officer by the name of Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky. “And suddenly Conchita starts getting thoughts in her head and she realizes she doesn’t have to settle for the life that Palomo has set up for them,” notes Cintron. “There’s not much Palomo can say and he’s almost jumping out of his skin to figure out what’s going on and what to do about it.”

And the rival for Conchita’s affections is formidable indeed.

“Juan Julian is a lover of stories, someone who still believes in romance and who gets caught up in saving Conchita from being left behind,” observes  Pimentel of the character he plays. “He gets involved much deeper than he probably intended, but he understands his place as a resource for this woman to understand a little better who she is and what a relationship should look like. He understands that he’s going leave, he’s going to step out of [his involvement with Conchita] at some point and leave the couple to sort things out.”

Pimentel of the character he plays. “He gets involved much deeper than he probably intended, but he understands his place as a resource for this woman to understand a little better who she is and what a relationship should look like. He understands that he’s going leave, he’s going to step out of [his involvement with Conchita] at some point and leave the couple to sort things out.”

While Pimentel doesn’t ascribe a name to the character of Juan Julian, it’s clear from both the context and storyline of Anna in the Tropics that he’s a classic rake in the tradition of Don Juan, Pablo Picasso or even former president Bill Clinton to use a more modern example.

While Pimentel doesn’t ascribe a name to the character of Juan Julian, it’s clear from both the context and storyline of Anna in the Tropics that he’s a classic rake in the tradition of Don Juan, Pablo Picasso or even former president Bill Clinton to use a more modern example.

“A woman is often deeply oppressed by the role of she is expected to play,” writes Robert Greene in his national bestseller, The Art of Seduction. “She is supposed to be the tender, civilizing force in society, and to want commitment and lifelong loyalty. But often her marriage and relationships give her not romance and devotion, but routine and an endlessly distracted mate.  It remains the abiding female fantasy to meet a man who gives totally of himself, who lives for her, even if only for a while.”

It remains the abiding female fantasy to meet a man who gives totally of himself, who lives for her, even if only for a while.”

And the currency with which the rake operates is language and words. “He is as promiscuous with words as he is with women,” Greene continues. “He chooses words for their ability to suggest, insinuate, hypnotize, elevate, infect.” And what he offers is pleasure for its own sake, desire with no strings. Part of his appeal is the forbidden, dangerous and taboo. It doesn’t matter that he will ultimately abandon her. To the contrary, the affair’s impending finality adds to its overall seduction.

Throughout history and literature, the rake is well aware of his charm, attraction and affect on the opposite sex. “He is happy with himself and the impact he causes on women,” Dave Pimentel amplifies. “As a man, I can relate. If you see some woman likes you, you feel proud about it even if you don’t act on it.”

Throughout history and literature, the rake is well aware of his charm, attraction and affect on the opposite sex. “He is happy with himself and the impact he causes on women,” Dave Pimentel amplifies. “As a man, I can relate. If you see some woman likes you, you feel proud about it even if you don’t act on it.”

“There’s textual evidence in the play that his character is there to help [Palomo and Conchita] restore their relationship,” Cintron breaks in.

Pimentel gives a knowing nod.

“He helps her rediscover herself as a woman. He shows her a new and different kind of love … a love that Palomo doesn’t understand and so he asks her to show him. ‘What can we discover and where can we go from here?’ he’s asking.”

“He helps her rediscover herself as a woman. He shows her a new and different kind of love … a love that Palomo doesn’t understand and so he asks her to show him. ‘What can we discover and where can we go from here?’ he’s asking.”

“In essence, Juan Julian is our sex therapist,” Cintron sums up.

“A very involved one,” Pimentel adds with a laugh.

But both men ultimately circle back to the subject of romance and the part it plays in Spanish culture.

“In movies, Spanish men are written as these romantic sensual, sexual beings,”  Cintron wryly observes. “Hispanics are very nostalgic. We’re very much in love with love. We celebrate a lot of things, a lot of beautiful things. But that doesn’t make us any more romantic than any other culture. I’ve seen Southern men be very romantic and African-American men be romantic with their wives. Perhaps we write about it and celebrate it more.”

Cintron wryly observes. “Hispanics are very nostalgic. We’re very much in love with love. We celebrate a lot of things, a lot of beautiful things. But that doesn’t make us any more romantic than any other culture. I’ve seen Southern men be very romantic and African-American men be romantic with their wives. Perhaps we write about it and celebrate it more.”

But what’s clear from the depiction of Palomo and Conchita’s relationship in Anna in the Tropics is the  necessity of maintaining and nurturing romance in every relationship. What opens the door to a Juan Julian or his female counterpart in any relationship is complacency, routine and being taken for granted – and that’s true across cultural lines. It’s a universal truth that Nilo Cruz so ably expresses through the characters in the play.

necessity of maintaining and nurturing romance in every relationship. What opens the door to a Juan Julian or his female counterpart in any relationship is complacency, routine and being taken for granted – and that’s true across cultural lines. It’s a universal truth that Nilo Cruz so ably expresses through the characters in the play.

And that’s the life lesson that Cintron and Pimentel hope audiences take away from the play.

“Life is complicated; it’s diverse,” Pimentel remarks. “Pressure from outside comes in so many different  ways. Remember your core values. Remember where you come from. Stick to what defines you as a person while still being open to new experiences and to learning.”

ways. Remember your core values. Remember where you come from. Stick to what defines you as a person while still being open to new experiences and to learning.”

“Latino, Hispanic culture is much like every other culture,” Cintron concurs. “We all have issues, passions and idiosyncrasies. Sometimes Latina women have to stand up for themselves. They are looking for a better life. Latino men are willing to change even though it’s difficult. We get angry, we forgive, we do all the same things that everybody else does. And you’ll see that in Anna in the Tropics.”

“Tolstoy understands  life better than anyone else,” chimes in another cast member, overhearing the conversation. “We are all the same even though we’re located in different places.”

life better than anyone else,” chimes in another cast member, overhearing the conversation. “We are all the same even though we’re located in different places.”

‘Nuff said.

Come see for yourself.

September 27, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

Lab celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month with ‘Anna in the Tropics’

Lab celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month with ‘Anna in the Tropics’- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ playwright Nilo Cruz

- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ director Annette Trossbach

- Spotlight on ‘Anna in the Tropics’ actor Miguel Cintron

- For ‘Anna in the Tropics,’ Rinaldo Chico Guido gets deadly serious

- ‘Heathers’ Chloe Tsai is dreamy as ‘Anna in the Tropics’ Marela Alcalar

- ‘Anna in the Tropics’ play dates, times and ticket info

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.