Cindy Jane

Genre: Surrealism

Galleries:

Website: http://www.cindyjane.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/cindy.jane

Her Art:

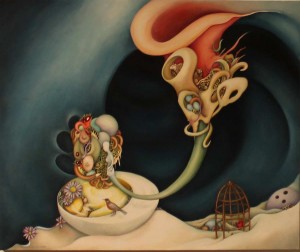

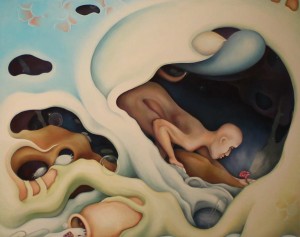

In the world of art, Cindy Jane stands apart. She characterizes herself as a Surrealist, but even within that genre, her art is without rival or comparison. It does not just explore an array of highly personal socio-political and metaphysical themes. Rather, Jane’s art invites – no, demands – contemplation of the impact on all life if we fail to protect our planet from the dangers implicit in genetic engineering, nanotechnology (the

In the world of art, Cindy Jane stands apart. She characterizes herself as a Surrealist, but even within that genre, her art is without rival or comparison. It does not just explore an array of highly personal socio-political and metaphysical themes. Rather, Jane’s art invites – no, demands – contemplation of the impact on all life if we fail to protect our planet from the dangers implicit in genetic engineering, nanotechnology (the  manipulation of matter on a molecular level) and climate change.

manipulation of matter on a molecular level) and climate change.

Many today predict an impending apocalypse, but destruction in most of these accounts is predicated on war, super-eruptions or celestial threats such as comets, meteors and asteroids. But destruction of life as we know it today could just as easily result from genetically-engineered super bugs, self-replicating matter-gobbling nanobots or super  storms like Hurricane Sandy.

storms like Hurricane Sandy.

“Our climate is changing,” said New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg following the storm. While the connection between Sandy and climate change is the subject of debate, a 2010 National Academy of Sciences report unequivocally found that global  surface temperatures have risen by roughly 1.4-degrees Fahrenheit over the last century, driven largely by burning fossil fuels that release warming “greenhouse” gases to the air. In addition, there is general agreement that sea levels have risen worldwide over the past century by about one foot due to climate change. Even more alarming is the

surface temperatures have risen by roughly 1.4-degrees Fahrenheit over the last century, driven largely by burning fossil fuels that release warming “greenhouse” gases to the air. In addition, there is general agreement that sea levels have risen worldwide over the past century by about one foot due to climate change. Even more alarming is the  prediction by a number of experts that sea levels will rise by as much as three feet this century due to the ice sheet melting in Greenland and elsewhere.

prediction by a number of experts that sea levels will rise by as much as three feet this century due to the ice sheet melting in Greenland and elsewhere.

Weighty concerns like these lie at the root of all Surrealism. In fact, it was despair over the devastation caused by World War I that gave rise to the seminal Surrealist movement of the early 1920s. Jane’s expression of the genre emanates  from the desolation she feels as she considers the deleterious impact that science, industry and modern society are wreaking on the environment on a daily basis. The ecological damage leads Jane to ponder through her art the regenerative aftermath of a post-apocalyptic world. “Life will go on,” Cindy states confidently, “but it won’t be the same.”

from the desolation she feels as she considers the deleterious impact that science, industry and modern society are wreaking on the environment on a daily basis. The ecological damage leads Jane to ponder through her art the regenerative aftermath of a post-apocalyptic world. “Life will go on,” Cindy states confidently, “but it won’t be the same.”

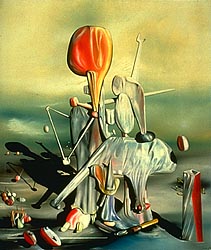

Thus, Jane’s paintings “delve into a world of  transgenic and geomorphic landscapes made up of agglomerative shapes that merge terrestrial, aquatic and celestial environments to create an ambiguous terrain with forms reminiscent of anatomical and botanical structures.” Some of the images that populate these environments include fish, birds and other familiar wild and botanical life. But her compositions also contain “enlarged microscopic elements [that] lie perilously suspended in fluid contours among motifs of birth and decay, while figurative and erotic elements help to shape a futuristic and ecological narrative.”

transgenic and geomorphic landscapes made up of agglomerative shapes that merge terrestrial, aquatic and celestial environments to create an ambiguous terrain with forms reminiscent of anatomical and botanical structures.” Some of the images that populate these environments include fish, birds and other familiar wild and botanical life. But her compositions also contain “enlarged microscopic elements [that] lie perilously suspended in fluid contours among motifs of birth and decay, while figurative and erotic elements help to shape a futuristic and ecological narrative.”

But Jane’s paintings are neither dark nor dreary. To the contrary, they simultaneously convey both hope and joy. The upbeat mood  expressed by Jane’s compositions derives partly from her tight pastel color palette, which gravitates towards soothing baby blues, spiritual violets and restful sea greens. The colors she chooses also engender harmonious transitions between multidimensional planes without the hard lines or modelling found in the Surrealist works of Breton, Dali or Yves Tanguy.

expressed by Jane’s compositions derives partly from her tight pastel color palette, which gravitates towards soothing baby blues, spiritual violets and restful sea greens. The colors she chooses also engender harmonious transitions between multidimensional planes without the hard lines or modelling found in the Surrealist works of Breton, Dali or Yves Tanguy.

The hopeful cast of Jane’s environments is also  achieved through a clever blend of familiar, friendly and non-threatening creatures (like dolphins, fish, birds, cows and even white rabbits) with unfamiliar morphed plants and microscopic anatomical structures. The juxtaposition imbues her compositions with immediacy. “The combination of familiar and unfamiliar is what draws you in,” observes urban expressionist

achieved through a clever blend of familiar, friendly and non-threatening creatures (like dolphins, fish, birds, cows and even white rabbits) with unfamiliar morphed plants and microscopic anatomical structures. The juxtaposition imbues her compositions with immediacy. “The combination of familiar and unfamiliar is what draws you in,” observes urban expressionist  Marcus Jansen. Which is what makes Jane’s contribution to the lexicon of the art world important. “It’s important for an artist to do something unfamiliar in a convincing way,” Jansen opines, which is precisely what makes his own art so collectable. There just isn’t anyone else doing what Jane and Jansen are doing in their respective genres. Each is totally unique. Each occupies his/her own niche.

Marcus Jansen. Which is what makes Jane’s contribution to the lexicon of the art world important. “It’s important for an artist to do something unfamiliar in a convincing way,” Jansen opines, which is precisely what makes his own art so collectable. There just isn’t anyone else doing what Jane and Jansen are doing in their respective genres. Each is totally unique. Each occupies his/her own niche.

“The use of anatomical shapes is not really the intention,” Jane clarifies. “I’m more interested in [naturally-occurring] repetitive shapes, contours and patterns.” Jane does a lot of gardening, which undoubtedly informs the organic imagery that populates the terrain her compositions depict. “It’s never about the objects or subjects,” Cindy adds. “It about the atmosphere within each painting.”

“The use of anatomical shapes is not really the intention,” Jane clarifies. “I’m more interested in [naturally-occurring] repetitive shapes, contours and patterns.” Jane does a lot of gardening, which undoubtedly informs the organic imagery that populates the terrain her compositions depict. “It’s never about the objects or subjects,” Cindy adds. “It about the atmosphere within each painting.”

If the Surrealism of Breton and Dali was a rejection of the reason and intellectualism that gave rise to the nihilism that led to and followed  World War I, then Jane’s surprising transformative imagery can be viewed as a rejection of the blind acceptance of the “convenience and benefits” provided by science and industry without regard to the harm they do to the ecology. But it is ultimately left to the viewer to ascribe meaning to Jane’s poignant and enigmatic landscapes. “I always prefer that the viewers interpret [my imagery] for themselves,” Cindy insists. “I don’t like to impose my meaning on them.” Instead, her goal is to open a dialogue between viewers and her paintings that they can contemplate for years to come. And that explains why Cindy Jane is clearly emerging as a talent of unique and resolute vision.

World War I, then Jane’s surprising transformative imagery can be viewed as a rejection of the blind acceptance of the “convenience and benefits” provided by science and industry without regard to the harm they do to the ecology. But it is ultimately left to the viewer to ascribe meaning to Jane’s poignant and enigmatic landscapes. “I always prefer that the viewers interpret [my imagery] for themselves,” Cindy insists. “I don’t like to impose my meaning on them.” Instead, her goal is to open a dialogue between viewers and her paintings that they can contemplate for years to come. And that explains why Cindy Jane is clearly emerging as a talent of unique and resolute vision.

[Paintings shown above are (1) Strange Seed; (2) Treasures Deep; (3) Return to Cradle; (4) The Impenetrable Bloom; and (5) Satyaaur Ahimsal.]

Bio

Completely self-taught, Jane has only been painting since 2004, although she began exhibiting after only a year of work in the medium. “A lot of experimentation,” is her ready explanation for her remarkable progress in both concept and technical prowess over that span. “A lot of experimentation.”

Completely self-taught, Jane has only been painting since 2004, although she began exhibiting after only a year of work in the medium. “A lot of experimentation,” is her ready explanation for her remarkable progress in both concept and technical prowess over that span. “A lot of experimentation.”

“I took a photography class years ago and that changed the way I looked at things,” Cindy explains. “At the same time, I was studying a little bit of art history [as well as drawing and basic design] at Edison Community College and became fascinated with painting and wanted to try it. I wanted to create things, not necessarily record them. I wanted that tactile quality that drawing and painting offer, and to have that connection to the work.”

Exhibitions and Shows

On February 1, 2013, Jane’s solo exhibition, Morphic Adaptations, opened at the prestigious Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center in the downtown Fort Myers River District. The show featured a series of large scale works that included a 60×86 inch diptych titled The Encroachment (left) and two 60×112 inch triptychs, Broken Bough and The Emergence (below right), provocative dystopian landscapes in which organic formations and archetypal figurative representations take center stage with lyrical eloquence.

On February 1, 2013, Jane’s solo exhibition, Morphic Adaptations, opened at the prestigious Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center in the downtown Fort Myers River District. The show featured a series of large scale works that included a 60×86 inch diptych titled The Encroachment (left) and two 60×112 inch triptychs, Broken Bough and The Emergence (below right), provocative dystopian landscapes in which organic formations and archetypal figurative representations take center stage with lyrical eloquence.

The show was both well-attended and well-received, with artist Marcus Jansen saying “Cindy has her own vocabulary and a different position than most other artists” in her genre; artist Daniel Venditti praising Jane’s unique ability to juxtapose “strong imagery with amazing softness and gentle transitions;” and fine art photographer Doug Heslep adding that Cindy’s “saturated and mind-

The show was both well-attended and well-received, with artist Marcus Jansen saying “Cindy has her own vocabulary and a different position than most other artists” in her genre; artist Daniel Venditti praising Jane’s unique ability to juxtapose “strong imagery with amazing softness and gentle transitions;” and fine art photographer Doug Heslep adding that Cindy’s “saturated and mind- blowing content is impossible to process in just a single view.”

blowing content is impossible to process in just a single view.”

In 2012, Jane had three paintings included in HOWL Gallery‘s Fourth Annual SWFL Lives! group show. That exhibition followed her solo show Pathos, Ethos and Origins at Arts for ACT Gallery in November of 2011. Cindy also  participated during 2011 in Arts for ACT’s Fourth Annual Open Theme Exhibition and daas Gallery’s Skin 2011 competition and exhibition, where her entry, Potent Elixir, was awarded Best of Show by a three-panel jury consisting of Canterbury School art instructor Nick Grey, Gulf Coast Times editor/writer Yahanna de la Torre, and professional photographer Suzanne Smith.

participated during 2011 in Arts for ACT’s Fourth Annual Open Theme Exhibition and daas Gallery’s Skin 2011 competition and exhibition, where her entry, Potent Elixir, was awarded Best of Show by a three-panel jury consisting of Canterbury School art instructor Nick Grey, Gulf Coast Times editor/writer Yahanna de la Torre, and professional photographer Suzanne Smith.

Potent Elixir gives insight into Cindy’s process. In the center of the composition is a nude female torso which appears to be under water, at least based on  the green bubbles and fish swimming above the figure’s two perfectly-formed pale breasts. But from there, the imagery gets sketchy and is filled with male and female genitalia. “I started with the figure in the center and then I just worked myself around the painting imaginatively. I didn’t plan ahead of time what I was going to do. I don’t like to have a preconceived idea of what I’m going to do. That way something unexpected always seems to happen.” Like the floppy-eared white rabbit in the lower left-hand portio of the canvas.

the green bubbles and fish swimming above the figure’s two perfectly-formed pale breasts. But from there, the imagery gets sketchy and is filled with male and female genitalia. “I started with the figure in the center and then I just worked myself around the painting imaginatively. I didn’t plan ahead of time what I was going to do. I don’t like to have a preconceived idea of what I’m going to do. That way something unexpected always seems to happen.” Like the floppy-eared white rabbit in the lower left-hand portio of the canvas.

This is how she prefers to work. “My paintings begin without preconception and take shape organically, as I work with biomorphic forms, repetitive patterns, and metaphorical imagery,” the artist shares. “I am interested in evolutionary processes within biological, cultural and socio-political parameters. Through an unconscious flow of ideas, I am often led to the unexpected, ambiguous and universal.”

A Rare Portrait

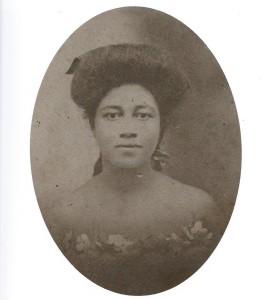

Cindy rendered a rare portrait for the Fort Myers Founding Females Portrait Exhibition, a show that draws attention to the contributions made by women like Dr. Ella Mae Piper to the early development of the City of Fort Myers. To be sure, Cindy’s likeness of Dr. Piper is spot on. But what makes the portrait so compelling is its allegorical content. She manages to include iconography that reflects all of the highlights of Dr. Piper’s rich and generous public life.

Cindy rendered a rare portrait for the Fort Myers Founding Females Portrait Exhibition, a show that draws attention to the contributions made by women like Dr. Ella Mae Piper to the early development of the City of Fort Myers. To be sure, Cindy’s likeness of Dr. Piper is spot on. But what makes the portrait so compelling is its allegorical content. She manages to include iconography that reflects all of the highlights of Dr. Piper’s rich and generous public life.

“Two things interested me most when I was introduced to the story of Dr. Ella Mae Piper,” Cindy shares. “First,  she was an educated, independent business woman during a time of racial segregation, women’s suffrage, and the Great Depression,” which were all rarities. “Second, she was a philanthropist who used her business earnings to fund projects to better the lives of, and increase opportunity for, the people in her community.”

she was an educated, independent business woman during a time of racial segregation, women’s suffrage, and the Great Depression,” which were all rarities. “Second, she was a philanthropist who used her business earnings to fund projects to better the lives of, and increase opportunity for, the people in her community.”

Dr. Piper arrived in Fort Myers in 1915, shortly after graduating the renowned Rohrer Institute of Beauty Culture in New York City. At the time, her mother, Sarah Williams, was a domestic worker employed in the home of banker/hotel owner/real estate developer, Harvie Heitman. But more, she also owned a great deal of property in the town.

Ella opened Fort Myers’ first beauty salon. It was on Jackson [across from Englehart’s Mortuary], but she later moved it to Hendry Street for a short time before changing the location to Evans Avenue, so she could work closer to her home. Dr. Piper also did chiropody (foot care), and among her clients were Clara Ford and Mina Edison, with whom she became close friends. Hence the reference in Cindy’s composition to the Fort Myers Beauty Parlor.

Ella opened Fort Myers’ first beauty salon. It was on Jackson [across from Englehart’s Mortuary], but she later moved it to Hendry Street for a short time before changing the location to Evans Avenue, so she could work closer to her home. Dr. Piper also did chiropody (foot care), and among her clients were Clara Ford and Mina Edison, with whom she became close friends. Hence the reference in Cindy’s composition to the Fort Myers Beauty Parlor.

Another of Dr. Piper’s business ventures was the Big 4 Bottling Company, which provided the town with soft drinks for a nickel a bottle, which Cindy also references in the portrait.

Over time, Ella Mae became a respected community activist, philanthropist and founding member of Safety Hill, as the postage stamp lettering along the left perimeter of the portrait depicts. White folks back then claimed that Safety Hill took its name from the fact that the ground was high enough to be safe from flooding during hurricanes and summer thunderstorms. But the folks living in Safety Hill knew that the subdivision was the only place blacks could feel safe during the days of racial segregation. But it wasn’t always that way.

Over time, Ella Mae became a respected community activist, philanthropist and founding member of Safety Hill, as the postage stamp lettering along the left perimeter of the portrait depicts. White folks back then claimed that Safety Hill took its name from the fact that the ground was high enough to be safe from flooding during hurricanes and summer thunderstorms. But the folks living in Safety Hill knew that the subdivision was the only place blacks could feel safe during the days of racial segregation. But it wasn’t always that way.

Prior to 1900, blacks and whites lived together. In fact, Fort Myers first black settler, Nelson Tillis, married a white woman and their 10 children played in the yard of newcomer Thomas Edison. But many of the people who moved into Fort Myers in the years following the turn of the 20th century were far less racially  tolerant and even imposed “Jim Crow” laws that made it a crime for “people of color” to cross the railroad tracks after dark. Cindy’s canvas is similarly divided by a set of stark, obtrusive rail lines.

tolerant and even imposed “Jim Crow” laws that made it a crime for “people of color” to cross the railroad tracks after dark. Cindy’s canvas is similarly divided by a set of stark, obtrusive rail lines.

Tillis couldn’t abide the growing racial tensions and left for the Bahamas, never to be seen again. But Dr. Piper resolved to make Safety Hill and the people who lived there the best they could be. When Sarah Williams died in 1926, Dr. Piper assumed her mother’s role in putting on an annual Christmas Tree Party for the children of Safety Hill, an event that continues to this day. Because of her stature, many churches,  businesses and community leaders, black and white, pitched in, contributing gifts and donations for the youngsters.

businesses and community leaders, black and white, pitched in, contributing gifts and donations for the youngsters.

A firm believer in education, Dr. Piper helped finance the construction of Dunbar Community School in 1927 so that black children from Lee, Charlotte and Collier County could get a high  school education, which was not possible prior to the school’s opening. She was instrumental in helping young people obtain scholarships to attend Tuskegee College, sometimes using her personal funds for this purpose, and also helped fund the Jones-Walker Hospital, which was the area’s first hospital for nonwhites, and establish a black chapter of the American Red Cross.

school education, which was not possible prior to the school’s opening. She was instrumental in helping young people obtain scholarships to attend Tuskegee College, sometimes using her personal funds for this purpose, and also helped fund the Jones-Walker Hospital, which was the area’s first hospital for nonwhites, and establish a black chapter of the American Red Cross.

Her personal philanthropy included giving food and clothing to needy neighbors, providing housing to Negro League baseball players who were denied accommodations at area hotels, and giving assistance to the handicapped and underprivileged elderly. When she died in 1954, she willed her home to the City of Fort Myers for “the benefit of young people and the elderly.” The new Dr. Ella Piper Center carries on her work today.

Her personal philanthropy included giving food and clothing to needy neighbors, providing housing to Negro League baseball players who were denied accommodations at area hotels, and giving assistance to the handicapped and underprivileged elderly. When she died in 1954, she willed her home to the City of Fort Myers for “the benefit of young people and the elderly.” The new Dr. Ella Piper Center carries on her work today.

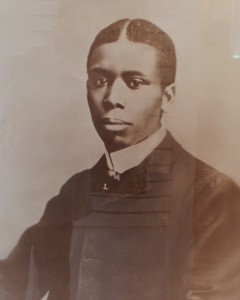

Safety Hill morphed in the 1940s into Dunbar, deriving its name from the high school that was named in honor of renowned black poet, author and playwright Paul Lawrence Dunbar. But whether you call the neighborhood Safety Hill or Dunbar, Dr. Piper was not just a founding member, she was a role model for people, black and white, throughout Fort Myers, who learned by her example lessons of grace and the importance of education, civic activism, and personal philanthropy.

Safety Hill morphed in the 1940s into Dunbar, deriving its name from the high school that was named in honor of renowned black poet, author and playwright Paul Lawrence Dunbar. But whether you call the neighborhood Safety Hill or Dunbar, Dr. Piper was not just a founding member, she was a role model for people, black and white, throughout Fort Myers, who learned by her example lessons of grace and the importance of education, civic activism, and personal philanthropy.

“I approached her portrait as if I were painting a portrait within a portrait, staying fairly true to the B&W vintage photograph I used as reference while making stylistic changes in the composition and  background,” Cindy explains. “She [was] a woman of great confidence and with some authority, so I placed her high on the canvas and brought her forward in an almost life-size depiction. I shifted her gaze slightly, so as to give her a more introspective appearance, as if she herself were reflecting upon her life and the difference that she made. She didn’t have any children of her own, and very little is known about her personal relationships. I believe this brought an air of mystery about her which I tried to express through the changing skies in the background.”

background,” Cindy explains. “She [was] a woman of great confidence and with some authority, so I placed her high on the canvas and brought her forward in an almost life-size depiction. I shifted her gaze slightly, so as to give her a more introspective appearance, as if she herself were reflecting upon her life and the difference that she made. She didn’t have any children of her own, and very little is known about her personal relationships. I believe this brought an air of mystery about her which I tried to express through the changing skies in the background.”

A Word about Biomorphism in Art

The term biomorphism refers to life (bio) and transformation (morphism). It was coined in 1935 by the British writer Geoffrey Grigson and subsequently used by Alfred H. Barr in the context of his 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art. Biomorphist art focuses on the power and resiliency of natural life, and uses organic shapes (with rounded, curvilinear and graceful free-form images that suggest the contours of plants and animals) as opposed to hard-lined geometrical forms.

The term biomorphism refers to life (bio) and transformation (morphism). It was coined in 1935 by the British writer Geoffrey Grigson and subsequently used by Alfred H. Barr in the context of his 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art. Biomorphist art focuses on the power and resiliency of natural life, and uses organic shapes (with rounded, curvilinear and graceful free-form images that suggest the contours of plants and animals) as opposed to hard-lined geometrical forms.

Biomorphism has connections with both Surrealism and Art Nouveau. It’s first appearance in the annals of art appears to be Matisse’s 1905 painting Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life). The Tate Gallery has posted an online article on biomorphic art. It states that while biomorphic forms are abstract, they “refer to, or evoke, living forms…” The Tate includes painters Joan Miró (1893-1983; Wadsworth Atheneum, 1933) and Jean Arp (1886-1966; Aquatique, 1953) and British sculptors Henry Moore (1898-1986; Reclining Mother and Child, 1961), and Barbara Hepworth (1903-75; Mother and Child, 1934) among artists whose work epitomizes the use of biomorphic form. Although both Dali (1904-89) and Magritte incorporated biomorphic forms in their Surrealist works, two other Surrealists, Yves Tanguy (1900-1955; Through Birds, through Fire, but Not through Glass, 1943, left) and Roberto Matta also beguiled and intrigued viewers with their unique and haunting biomorphic images. Matta, in particular, blended organic and cosmic life forms in his compositions.

Biomorphism has connections with both Surrealism and Art Nouveau. It’s first appearance in the annals of art appears to be Matisse’s 1905 painting Le bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life). The Tate Gallery has posted an online article on biomorphic art. It states that while biomorphic forms are abstract, they “refer to, or evoke, living forms…” The Tate includes painters Joan Miró (1893-1983; Wadsworth Atheneum, 1933) and Jean Arp (1886-1966; Aquatique, 1953) and British sculptors Henry Moore (1898-1986; Reclining Mother and Child, 1961), and Barbara Hepworth (1903-75; Mother and Child, 1934) among artists whose work epitomizes the use of biomorphic form. Although both Dali (1904-89) and Magritte incorporated biomorphic forms in their Surrealist works, two other Surrealists, Yves Tanguy (1900-1955; Through Birds, through Fire, but Not through Glass, 1943, left) and Roberto Matta also beguiled and intrigued viewers with their unique and haunting biomorphic images. Matta, in particular, blended organic and cosmic life forms in his compositions.

Arshile Gorky also developed a biomorphic style of abstraction during the 1930s. Influenced by Miro and Arp, his important series of paintings and gouache studies known as the Garden in Sochi works marks Gorky’s transition from the biomorphism of Joan Miró to his own independent painting style after a two-decades-long apprenticeship to a series of modern artists. The brightly colored, free-floating forms of these works memorialize his father’s garden in the Armenian village of Khorkom, near Lake Van, although the deliberately obfuscating title confusingly references the Russian Black Sea resort of Sochi, in line with Gorky’s efforts to camouflage his background. Gorky later described his father’s garden as filled with poplars and apple trees, as well as “incalculable amounts of wild carrots,” and he based these paintings on his childhood memories of this idyllic place as filtered through Miró’s lexicon of abbreviated natural forms.

However, as the biomorphism embraced by these artists springs from different concerns, it is much different than Jane’s iteration of the genre. Artists like Dali, Magritte, Miro, Arp and Gorky were inspired not to build or construct rationally, but to emulate the germinal forces found in nature. Their biomorphism emerged as the result of a cluster of ideas about nature, automatism (the painterly technique for Freudian free association), mythology and the unconscious. Jane’s inspiration inheres in the conviction that life will go on in spite of any biological cataclysm that may befall mankind. Thus, her biomorphism combines both abstract and representational imagery which is uniquely transgenic, evolutionary and geomorphic. In that, she stands alone and her artwork is without equal or even parallel.

Fast Facts.

- Cindy and her husband are planning a garden based on permaculture principles. Once installed, it will integrate non-invasive food-bearing plants with medicinal cultivated species under a “forest” canopy of trees, with energy being provided by solar and wind-generated sources.

Articles and Links.

Surrealist Cindy Jane joining Union Artist Studios April 1 (03-16-14)

Surrealist Cindy Jane joining Union Artist Studios April 1 (03-16-14)- Surrealist Cindy Jane’s Morphic Adaptations exceeds expectations (02-04-13)

- It’s ‘Morphic Adaptation’ time at Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center (02-01-13)

- Musician Peter Taylor to provide ambient sound for ‘Morphic Adaptations’ exhibit (01-15-13)

- The new art of Cindy Jane opens for Art Walk at the Davis Art Center (01-14-13)

- Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center announces culturally rich February schedule (01-14-13)

- Cindy Jane’s surrealism reacts to planetary threats from science and industry (01-09-13)

- Local artist Cindy Jane pioneer in genre of modern biomorphic surrealism (12-22-12)

- Modern biomorphic surrealist Cindy Jane to exhibit at Davis in February (12-15-12)

- Surrealist Cindy Jane to exhibit at Arts for ACT in November (09-25-11)

- Conversation with Skin 2011 Best in Show artist Cindy Jane -2 (07-13-12)

- Conversation with Skin 2011 Best in Show artist Cindy Jane (07-13-11)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.