River Basin

“Think of the new river basin as a canvas,” Assistant City Manager Marc Collins urged the Fort Myers Public Art Committee in June of 2012. “Rather than a place for one piece of art, the new basin will be the site for multiple artworks; an economic engine to incorporate arts into the entire downtown. And not just the visual arts. It will be a public space that can be used by dancers, musicians and performers from the Florida Repertory Theatre.”

“Think of the new river basin as a canvas,” Assistant City Manager Marc Collins urged the Fort Myers Public Art Committee in June of 2012. “Rather than a place for one piece of art, the new basin will be the site for multiple artworks; an economic engine to incorporate arts into the entire downtown. And not just the visual arts. It will be a public space that can be used by dancers, musicians and performers from the Florida Repertory Theatre.”

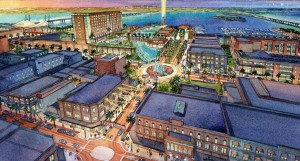

To help Public Art Committee members Ava Roeder, Sharon McAllister, Janet McCormack, Gwen Middlebrooks, William Taylor, David Acevedo and Patricia Collins envision the possibilities, Collins flashed a number of artists’ renderings across the monitors stationed in front of each of them. The drawings depicted a 1.8 acre inlet of water extending from the Caloosahatchee River all the way to Bay Street, lined on three sides by a 10-foot wide sidewalk edged by a wire cable railing anchored by 48 concrete pedestals that have smooth faces designed for murals, frescoes or perhaps bas reliefs.

To help Public Art Committee members Ava Roeder, Sharon McAllister, Janet McCormack, Gwen Middlebrooks, William Taylor, David Acevedo and Patricia Collins envision the possibilities, Collins flashed a number of artists’ renderings across the monitors stationed in front of each of them. The drawings depicted a 1.8 acre inlet of water extending from the Caloosahatchee River all the way to Bay Street, lined on three sides by a 10-foot wide sidewalk edged by a wire cable railing anchored by 48 concrete pedestals that have smooth faces designed for murals, frescoes or perhaps bas reliefs.

“There will also be four monuments on Edwards Drive,” points out Don Paight, Executive Director of the Fort Myers Redevelopment Agency. “They will be 13 feet high and there will be an opportunity to place artwork on them that’s visible from the street.” Public art will be needed for the gateway that will be constructed at Hendry and Bay to mark the transition from the riverfront into Fort Myers’ historic downtown district.

“There will also be four monuments on Edwards Drive,” points out Don Paight, Executive Director of the Fort Myers Redevelopment Agency. “They will be 13 feet high and there will be an opportunity to place artwork on them that’s visible from the street.” Public art will be needed for the gateway that will be constructed at Hendry and Bay to mark the transition from the riverfront into Fort Myers’ historic downtown district.

While Collins and Paight are thinking in terms of 2-dimensional art, artists will be invited to submit proposals for the basin project that could certainly opt instead to use the stanchions and monuments as pedestals for either free-standing, spiral or wraparound sculptures made from Corten, stainless steel, aluminum or even dicroic-coated panels containing solar-powered luminaries that light up after dark. Their only restrictions will be budgetary and the need to use materials that won’t rust or corrode in the hot, wet environ of the water feature.

While Collins and Paight are thinking in terms of 2-dimensional art, artists will be invited to submit proposals for the basin project that could certainly opt instead to use the stanchions and monuments as pedestals for either free-standing, spiral or wraparound sculptures made from Corten, stainless steel, aluminum or even dicroic-coated panels containing solar-powered luminaries that light up after dark. Their only restrictions will be budgetary and the need to use materials that won’t rust or corrode in the hot, wet environ of the water feature.

Ultimately, it will be up to the Public Art Committee to determine the project’s parameters and scope when they issue their call to artists in the coming weeks. And that’s when the fun really begins.

N.B.: The last time the Public Art Committee issued a call for qualifications, 162 artists responded to the Art Committee’s call. The Committee winnowed that pool of talent down to three finalists, with David Black winning the competition with his proposal for Fire Dance, the newest addition to the city’s public art collection.

Fort Myers new river basin discharges city’s obligations as stewards of the Caloosahatchee’s health

Since the day Brevet Major Ridgely of the 4th U.S. Artillery sailed up the Caloosa River and landed on the site of the ruins of long-abandoned Fort Harvie with orders to build a new and expanded military outpost, Fort Myers has enjoyed a special relationship with the Caloosahatchee River. Fort Myers’ first settlers, Manuel A. Gonzalez and his son, came by boat. Tarpon fishing and the river’s scenic beauty were what attracted early developers like Ambrose and Tootie McGregor to the fledgling town. These factors were also important to Thomas Edison, who liked to wet a line himself from time to time.

Since the day Brevet Major Ridgely of the 4th U.S. Artillery sailed up the Caloosa River and landed on the site of the ruins of long-abandoned Fort Harvie with orders to build a new and expanded military outpost, Fort Myers has enjoyed a special relationship with the Caloosahatchee River. Fort Myers’ first settlers, Manuel A. Gonzalez and his son, came by boat. Tarpon fishing and the river’s scenic beauty were what attracted early developers like Ambrose and Tootie McGregor to the fledgling town. These factors were also important to Thomas Edison, who liked to wet a line himself from time to time.

“Until the railroad came in 1904, most goods and supplies came to Fort Myers via boat,” notes historian Gina Taylor of True Tours. Beginning with the fort, a series of piers were built across the shoals in order to facilitate unloading the boats that plied the Caloosahatchee’s wide waters. Even Thomas Edison built a pier when he purchased his acreage on the river so that workers had a place to off-load his pre-cut house, The Seminole Lodge, when it arrived by schooner from Maine.

But the city not only owes its existence to the river, it has a duty as its steward to preserve and protect the Caloosahatchee’s waters. And those waters are sick. Not just sick. Endangered. In fact, American Rivers named the Caloosahatchee in 2006 as the 7th most endangered river in the nation.

“The scale of the damage to water quality, aquatic habitat, fish and wildlife … [is] a national level ecological tragedy,” said American Rivers, noting that intense algae blooms have severely depleted oxygen levels in the Caloosahatchee, resulting in the decimation of the river’s commercial seafood and sports fishing species. Since 2000, there have been 570 days when the algae has been so bad that health officials have been compelled to issue orders prohibiting swimming in the river.

“The scale of the damage to water quality, aquatic habitat, fish and wildlife … [is] a national level ecological tragedy,” said American Rivers, noting that intense algae blooms have severely depleted oxygen levels in the Caloosahatchee, resulting in the decimation of the river’s commercial seafood and sports fishing species. Since 2000, there have been 570 days when the algae has been so bad that health officials have been compelled to issue orders prohibiting swimming in the river.

Five National Wildlife Refuges depend on the Caloosahatchee River for water, including J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Caloosahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, Island Bay National Wildlife Refuge, Matlacha Pass National Wildlife Refuge, and Pine Island National Wildlife Refuge. Many are showing signs of impaired ecosystems as a result of the polluted waters of the Caloosahatchee. Estuaries at the river’s mouth have suffered devastating damage. Hundreds of square miles of the Gulf of Mexico are also adversely impacted by the freshwater plume emanating from the Caloosahatchee River.

Much of the damage is attributable discharges from Lake Okeechobee. During the 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons, for example, heavily-polluted releases were discharged into the Caloosahatchee to prevent flooding around the lake. But that only accounted for 40 percent of the pollutants found in the river and its fragile gulfside estuaries. The other 60 percent was attributable to stormwater runoff, with the River District being a major source of contaminants.

And that’s what gave rise to the River District’s new 1.8 water basin. While the inlet will bestow numerous business, historic and artistic opportunities, its primary purpose is to improve water quality in the Caloosahatchee River by serving as a stormwater detention pool that collects and filters water from the surrounding 15-acre downtown area. Percolating fountains aerate the water while plants absorb fertilizers and other nutrients that don’t belong in the Caloosahatchee.

“I equate it to a pool filter,” analogizes Don Paight, Executive Director of Fort Myers Redevelopment Agency, who notes that these environmental benefits also helped the city secure about $900,000 in grants from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Funding also included about $2.5 million left over from bond money the city borrowed for the Streetscape project.

But just as the need to screen cars in the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage from public view gave rise to New York artist Marylyn Dintenfass’ 30,000-square-foot Parallel Park public art installation that has the whole nation calling Fort Myers an art center, the basin too will give rise to opportunities in a number of different sectors.

The next phase of the redevelopment project includes tripling the size of Harborside Event Center and adding an adjoining 12-story, 220-room convention-quality hotel that will overlook the basin and a wide swath of the Caloosahatchee River. Walkways and shops will ultimately surround the new basin, with as many as four new restaurants making the basin their new home. And as Assistant City Manager Marc Collins told the Public Art Committee in June, the basin will ultimately provide space for upwards of a hundred new pieces of public artwork, thereby firmly establishing Fort Myers as a locale where “the arts mean business.”

Once completed, the combined riverfront/River District will be poised to attract conventions, business meetings, tourists and new residents. In fact, Aquest Realty, the city’s lead planner for the Riverfront Redevelopment Plan, estimates that the redevelopment could generate $376 million in spending and 3,000 jobs, with ongoing operation generating 780 jobs and $4 million in tax revenue each year. And by engrafting a public art component on the new aesthetic landscape, the community’s nonprofit arts and cultural organizations will be even better equipped to build upon the 2,000 jobs, 522,000 out-of-town cultural tourists and $68.3 million in revenues they currently contribute to the area’s economy each year.

As with Parallel Park, necessity can spawn invention. At its heart, the basin affords the city of Fort Myers with the opportunity to reinvent itself as a convention destination, an arts and cultural center, and a shining example of how people and businesses can flourish when city leaders and planners address ecological problems with imagination and foresight.

Fast Facts.

- Long ago, the Caloosahatchee River and Lake Okeechobee were separate bodies of water.

- In the 1890s, a Philadelphia businessman and real estate developer by the name of Hamilton Disston had a canal was constructed connecting Lake Okeechobee to Lake Hicpochee, from which the Caloosahatchee springs. In order to make the river navigable and keep Lake Okeechobee from flooding its southern perimeter, Disston also had the river channelized to remove its many oxbows.

- Releases of water from Lake Okeechobee into the river totalled approximately 855 billion gallons in 2005. That’s 44% of the total Lake Okeechobee discharge volume from 1996 to 2005.

- A South Florida Water Management District study found that from 1993 to 2003, Lake Okeechobee was responsible for nearly 40% of the nutrient input the Caloosahatchee River received. This number may have been even higher in the very wet 2004 and 2005 years.

- The high levels of nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorous, that come from Lake Okeechobee contribute to algae blooms. The discharges also contain high levels of sediments that can smother sea grass beds.

- The other 60% of the nutrients the Caloosahatchee receives comes from its own watershed where urban and agricultural run-off and inputs from densely-developed areas dependent on septic systems. Stormwater from these areas also represents a significant source of pollution for the river.

- Rivers in Florida have been named to American River’s endangered list 5 times in the past 21 years: the Everglades in 1992 and 1993, Chattahoochee River in 1998, Apalachicola River in 2002, and the Peace River in 2004. The purpose of this list is to heighten awareness among the public and the local, state, and national officials in an effort to prompt action.

Articles.

- River basin first step in rebranding Fort Myers convention and tourist locale -1 (12-09-12)

- River basin first step in rebranding Fort Myers convention and tourist locale -1 (12-09-12)

- Born of necessity, new river basin gives Fort Myers chance to reinvent itself (11-30-12)

- Fort Myers river basin provides opportunity for dozens of public artworks (06-22-12)

- Study says Lee’s arts industry generated $68 Million for county in 2010 (06-08-12)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.