Parallel Park

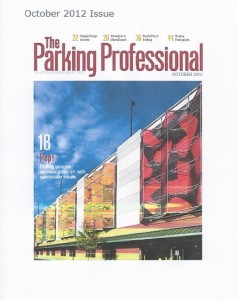

In most places, utilitarian concrete parking garages blight rather than enhance urban environments, but Parallel Park has transformed the 5-story Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage into a work of fine art that has first time visitors asking “Is this the fine art museum?”

Where it is

The Lee County Justice Center parking garage is located at the intersection of Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard and Monroe Street on the southern border of the downtown Fort Myers River District. The parking garage’s street address is 2116 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, Fort Myers, FL 33901. Its map coordinates are Latitude N 26 degrees 38′ and 26.2608″ and Longitude W 81 degrees, 52′ and 20.3102.”

The Lee County Justice Center parking garage is located at the intersection of Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard and Monroe Street on the southern border of the downtown Fort Myers River District. The parking garage’s street address is 2116 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, Fort Myers, FL 33901. Its map coordinates are Latitude N 26 degrees 38′ and 26.2608″ and Longitude W 81 degrees, 52′ and 20.3102.”

What it is

Dedicated on December 9, 2010, Parallel Park is a site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation. It consists of 23 open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels that have been attached to the exterior of the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage by aluminum tubes. Each panel stands 33 feet tall by 22 feet wide and the

Dedicated on December 9, 2010, Parallel Park is a site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation. It consists of 23 open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels that have been attached to the exterior of the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage by aluminum tubes. Each panel stands 33 feet tall by 22 feet wide and the  images change right before the viewer’s eyes as the sun carves its daily arc and clouds scurry across the bright blue Florida sky.

images change right before the viewer’s eyes as the sun carves its daily arc and clouds scurry across the bright blue Florida sky.

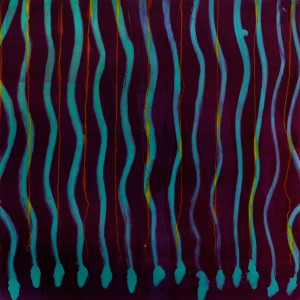

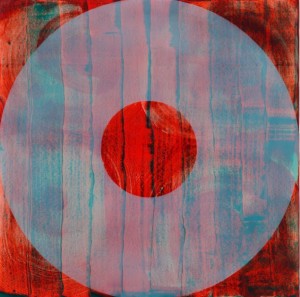

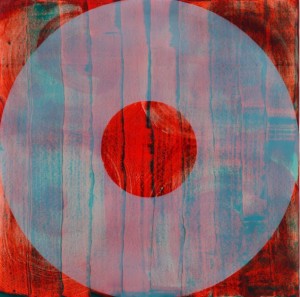

Each panel is a blow-up of an abstract painting that artist Marylyn Dintenfass created in her atelier. For example, the fire engine red and yellow-orange panels on the east façade of the building came from an oil-on-paper monotype titled Solstice (below right).

Not only do the panels engage the viewer kinetically, they tell a story. The characters in Dintenfass’ novel are color, shape, scale and pattern, and each side of the building represents a new chapter. But by the time you circle the building, the sun and clouds have changed position, and you are presented with four new chapters in this never-ending story.

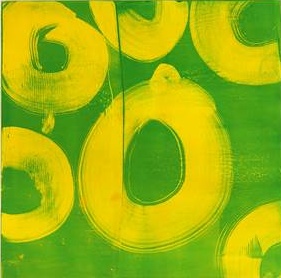

Taken together, the 23 panels “metaphorically express the spirit of the automobile.” It’s a subject with which Dintenfass  has had a love affair since before the time she could drive. “The circle shapes conjure tires, headlights, dashboard instrumentation and steering wheels,” Marylyn explains. “Linear patterns are emblematic of roads, ramps, directions and parking designations.” Dintenfass’ iconography of postwar American automotive culture directly integrates her interpretation of mobility and space with the fundamental purpose of a parking garage. It’s an apt simile given that Fort Myers’ was the winter home of Henry Ford

has had a love affair since before the time she could drive. “The circle shapes conjure tires, headlights, dashboard instrumentation and steering wheels,” Marylyn explains. “Linear patterns are emblematic of roads, ramps, directions and parking designations.” Dintenfass’ iconography of postwar American automotive culture directly integrates her interpretation of mobility and space with the fundamental purpose of a parking garage. It’s an apt simile given that Fort Myers’ was the winter home of Henry Ford  and Harvey Firestone, two of the leading pioneers of the American automobile industry.

and Harvey Firestone, two of the leading pioneers of the American automobile industry.

At first glance, people are impressed by the sheer size and scale of the installation. At 30,000 square feet, it’s big. Really big. But its not the scale, but rather the colors that draw you to the structure. Filmmaker Julie Mintz calls them “crazy colors … outside the natural palette.” Dintenfass lays yellow-oranges alongside crimson red like a Good Humor bomb pop, and she distills her greens from forest moss and ocean plankton.

Now that the colors have captured your attention, Dintenfass sets the hook by infusing her panels with movement. The darn things change from one moment to the next based on the intensity of the sunlight, the movement of the sun, and the action of the wind and clouds. One minute the panels appear solid. The next, they seemingly disappear. Dintenfass calls her panels transparent and

Now that the colors have captured your attention, Dintenfass sets the hook by infusing her panels with movement. The darn things change from one moment to the next based on the intensity of the sunlight, the movement of the sun, and the action of the wind and clouds. One minute the panels appear solid. The next, they seemingly disappear. Dintenfass calls her panels transparent and  ephemeral. Someone else might experience them as magical or even mystical.

ephemeral. Someone else might experience them as magical or even mystical.

The images and patterns also change as you walk around the building and alter your distance and perspective.

Up close, you can’t help but marvel at the open weave Kevlar/fiberglass fabric out of which the panels are constructed. The fabric is designed to  last in the rain, heat and humidity that characterizes southwest Florida’s harsh summers. To ensure that they have a useful life of a decade or more, the printer used archival ink and then coated the panels with an ultraviolet screening that resists fading.

last in the rain, heat and humidity that characterizes southwest Florida’s harsh summers. To ensure that they have a useful life of a decade or more, the printer used archival ink and then coated the panels with an ultraviolet screening that resists fading.

From across the street or a block away, it’s the difference between studying a single tree or gazing at the entire forest. The net result is a work of art emancipated from the confines of the frame.

How it was made

The installation was the brainchild of Kevin Williams (left) of BSSW Architects, who opted to use art panels consisting of open-weave Kevlar fabric to comply with a building ordinance that requires that parked cars be obscured from public view. “I was familiar with the material from Europe, where they use it in historical preservation,” Williams explains. “The saw tooth pattern of the tubular attachments holds the panels on even in high winds, facilitates air circulation and ventilation inside the structure,

The installation was the brainchild of Kevin Williams (left) of BSSW Architects, who opted to use art panels consisting of open-weave Kevlar fabric to comply with a building ordinance that requires that parked cars be obscured from public view. “I was familiar with the material from Europe, where they use it in historical preservation,” Williams explains. “The saw tooth pattern of the tubular attachments holds the panels on even in high winds, facilitates air circulation and ventilation inside the structure,  and permits people to view the artwork up close as well as from a distance.” Converting Williams’ design concept into reality was a collaborative effort between Lee County, the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee, New York abstract artist Marylyn Dintenfass, a printer located in North Carolina and a fabricator in Orlando, with the artist’s New York gallery, Babcock Galleries, providing publicity and media relations.

and permits people to view the artwork up close as well as from a distance.” Converting Williams’ design concept into reality was a collaborative effort between Lee County, the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee, New York abstract artist Marylyn Dintenfass, a printer located in North Carolina and a fabricator in Orlando, with the artist’s New York gallery, Babcock Galleries, providing publicity and media relations.

“The architects had determined the overall scope of the project: the fabricator, printer and materials had been  selected, and the framework to support the panels was already installed on the building. The next step was to commission an artist to create a 30,000 square-foot work of art that would be permanently installed on the structure,” notes Barbara Hill, the Public Art Committee’s art advisor in 2009. “For Fort Myers’ public art collection, a highly visible work of art by a distinguished artist could be a crowning achievement, a groundbreaking architectural landmark to put Fort Myers on the global public art map.”

selected, and the framework to support the panels was already installed on the building. The next step was to commission an artist to create a 30,000 square-foot work of art that would be permanently installed on the structure,” notes Barbara Hill, the Public Art Committee’s art advisor in 2009. “For Fort Myers’ public art collection, a highly visible work of art by a distinguished artist could be a crowning achievement, a groundbreaking architectural landmark to put Fort Myers on the global public art map.”

Due to time constraints, Hill and the PAC pursued an abbreviated search process (“a shortened version of what we have come to expect on weekly reality shows”) that resulted in a commission for the work being issued to Dintenfass. “Even though the project seemed innovative and appealingly expansive, I hesitated,” the artist noted in a May, 2012 article she wrote for NY Arts Magazine.

Due to time constraints, Hill and the PAC pursued an abbreviated search process (“a shortened version of what we have come to expect on weekly reality shows”) that resulted in a commission for the work being issued to Dintenfass. “Even though the project seemed innovative and appealingly expansive, I hesitated,” the artist noted in a May, 2012 article she wrote for NY Arts Magazine.  “After completing more than two dozen large-scale installations in the public realm, I was well-versed in the pain-to-pleasure ratio of public art commissions and knew the scales often tip towards trouble. Yet, there was a lascivious appeal to this project; especially as I contemplated the opportunity to further engage my long-standing love affair with cool, hot rock n’ roll-era muscle

“After completing more than two dozen large-scale installations in the public realm, I was well-versed in the pain-to-pleasure ratio of public art commissions and knew the scales often tip towards trouble. Yet, there was a lascivious appeal to this project; especially as I contemplated the opportunity to further engage my long-standing love affair with cool, hot rock n’ roll-era muscle  cars that I grew up with and lusted after. The thought of giving a tricked-out, sweet embrace to a pedestrian garage was intoxicating.”

cars that I grew up with and lusted after. The thought of giving a tricked-out, sweet embrace to a pedestrian garage was intoxicating.”

Once on board, Dintenfass went to work adapting her existing body of 35-inch square oil-on-paper monotypes to the size and scale of the parking garage in order to create, in the assessment of art curator Jennifer McGregor, “an entirely new new rhythm, a sequential frieze-like cadence that you do not get from the original monotypes.

Each of the eight monotypes that Dintenfass selected for the project was photographed, drum-scanned and enlarged to ten times its original size using specialized digitizing software. The resulting images were then printed on massive 33’ x 22’ open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels using archival ink and coated with a protective ultraviolet screening to ensure long-life durability.

Each of the eight monotypes that Dintenfass selected for the project was photographed, drum-scanned and enlarged to ten times its original size using specialized digitizing software. The resulting images were then printed on massive 33’ x 22’ open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels using archival ink and coated with a protective ultraviolet screening to ensure long-life durability.  The open-weave Kevlar fabric was chosen by architect Kevin Williams not because it served as an ideal support for Dintenfass’ artwork, but rather to fulfill a city ordinance that requires a parking garage to have open walls for air circulation while obscuring parked cars from public view.

The open-weave Kevlar fabric was chosen by architect Kevin Williams not because it served as an ideal support for Dintenfass’ artwork, but rather to fulfill a city ordinance that requires a parking garage to have open walls for air circulation while obscuring parked cars from public view.

“Although ideal for variable weather, Kevlar (initially used in race car tires and, more recently, in bulletproof vests) is not quite ideal as a material for the application of archival inks by large commercial digital printers.” The material, which is 50% empty spaces, also presented challenges for preserving Dintenfass’ highly saturated color

“Although ideal for variable weather, Kevlar (initially used in race car tires and, more recently, in bulletproof vests) is not quite ideal as a material for the application of archival inks by large commercial digital printers.” The material, which is 50% empty spaces, also presented challenges for preserving Dintenfass’ highly saturated color  palette and technique of overlaying multiple colors to achieve nuanced hues.

palette and technique of overlaying multiple colors to achieve nuanced hues.

“For the final process,” writes the artist in her NY Arts piece, “I needed to permeate the material with a high-density application of pure color that would fully engage the viewer with my iconic automotive motifs. I wanted to invoke movement and mobility, knowing the colors would change with the rotation of natural light from day to night and from season  to season.” Where most public art serves to extend the architecture of the building for which it is intended, “in this case,” notes art critic Michele Cohen, “the art envelopes the architecture.” Or better still, disguises the building so that passers-by are not even aware that it is, in reality, just a parking garage.

to season.” Where most public art serves to extend the architecture of the building for which it is intended, “in this case,” notes art critic Michele Cohen, “the art envelopes the architecture.” Or better still, disguises the building so that passers-by are not even aware that it is, in reality, just a parking garage.

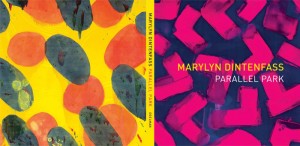

The Book

The making of Parallel Park is the subject of a new book by author Aliza Edelman. Released October 11, 2011, the monograph entitled Marylyn Dintenfass Parallel Park details the conception, planning and installation of the monumental art project. The book is published by Hard Press Editions in association with Hudson Hills Press and its release coincides with the opening of an exhibit of new work by the artist by her New York gallery, Driscoll Babcock Galleries in Chelsea on Manhattan. The exhibition, appropriately titled Souped Up/Tricked Out runs from October 11 through November 18, 2011.

The making of Parallel Park is the subject of a new book by author Aliza Edelman. Released October 11, 2011, the monograph entitled Marylyn Dintenfass Parallel Park details the conception, planning and installation of the monumental art project. The book is published by Hard Press Editions in association with Hudson Hills Press and its release coincides with the opening of an exhibit of new work by the artist by her New York gallery, Driscoll Babcock Galleries in Chelsea on Manhattan. The exhibition, appropriately titled Souped Up/Tricked Out runs from October 11 through November 18, 2011.

.

Why Marylyn Dintenfass?

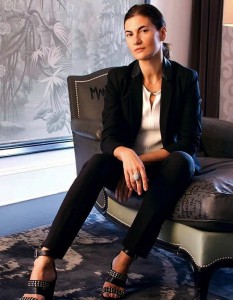

Marylyn Dintenfass is an internationally-recognized artist whose work is found in public and private collections in Italy, Denmark, Israel, Japan and the United States. More than 30 public collections hold her work including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Art, Museum of Fine Art in Houston, the Flint Institute of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She has been featured in more than a dozen solo exhibitions across the Unites States, including the Queens Museum of Art, the Katonah Museum, the Mississippi Museum of Art (an exhibition underwritten by the Andy Warhol Foundation) and her one-woman

Marylyn Dintenfass is an internationally-recognized artist whose work is found in public and private collections in Italy, Denmark, Israel, Japan and the United States. More than 30 public collections hold her work including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Art, Museum of Fine Art in Houston, the Flint Institute of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She has been featured in more than a dozen solo exhibitions across the Unites States, including the Queens Museum of Art, the Katonah Museum, the Mississippi Museum of Art (an exhibition underwritten by the Andy Warhol Foundation) and her one-woman  show in January 2011 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Edison State College in Fort Myers (see articles linked below).

show in January 2011 at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Edison State College in Fort Myers (see articles linked below).

In addition to solo exhibitions, Dintenfass has participated in more than 60 international group exhibitions since the 1970s. Twice, Dintenfass has been a MacDowell Fellow and she has received both an individual Artist Fellowship Grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts and two  project grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. She was awarded the Silver Medal at the First International, Mino, Japan, and the Ravenna Prize at the 45th Faenza International in Italy. Marylyn Dintenfass has also been a visiting professor at academic institutions in Canada, Norway, Holland and Israel, and for 10 years was a member of the faculty at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. A monograph of her

project grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. She was awarded the Silver Medal at the First International, Mino, Japan, and the Ravenna Prize at the 45th Faenza International in Italy. Marylyn Dintenfass has also been a visiting professor at academic institutions in Canada, Norway, Holland and Israel, and for 10 years was a member of the faculty at the Parsons School of Design in New York City. A monograph of her  work, Marylyn Dintenfass Paintings, was recently published by Hudson Hills Press.

work, Marylyn Dintenfass Paintings, was recently published by Hudson Hills Press.

Including Parallel Park, Dintenfass has completed 26 large-scale public art installations including the 42nd Street Bus Terminal at the New York Port Authority, the State of Connecticut Superior Courthouse, the Baltimore Federal Financial Building, IBM’s offices in Atlanta, Charlotte and San Jose, Ben Gurion University in Israel and Tagimi Middle School in Japan.

An experiential artist, Dintenfass operates from the premise that art is interactive and its interpretation is therefore influenced by the viewer’s experiences, perspective and how they connect with the motif. Art critic Lilly Wei observes that the stripes and circles that unite Dintenfass’s body of work “suggest kaleidoscopically spun close-ups of particles, waves and atoms, the magnified, colorized, deconstructed constituents of matter, filtered … into anti-matter, the anti-natural.”

Dintenfass was selected in July of 2009 to create Parallel Park following a truncated nationwide search of qualified artists, and both the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee and the residents of southwest Florida feel honored and lucky to have attracted an artist of such international stature. Their confidence in Dintenfass has been well rewarded as the artist continues to draw international attention to Fort Myers and the surrounding community as she mentions Parallel Park and Southwest Florida at each new exhibition, interview and appearance.

Dintenfass was selected in July of 2009 to create Parallel Park following a truncated nationwide search of qualified artists, and both the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee and the residents of southwest Florida feel honored and lucky to have attracted an artist of such international stature. Their confidence in Dintenfass has been well rewarded as the artist continues to draw international attention to Fort Myers and the surrounding community as she mentions Parallel Park and Southwest Florida at each new exhibition, interview and appearance.

For the latest, please visit https://www.marylyndintenfass.com/.

Why Kevin Williams?

Kevin Williams is a partner in BSSW Architects, Inc., whose offices are located at 1500 Jackson Street #200, Fort Myers, FL 33901-2929 (left). It is the largest architectural firm headquartered in southwest Florida. Its reputation has been built on innovation and performance, backed by consideration of each project’s surroundings and respect for client budgets and schedules. Williams and BSSW had been selected as architects for the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage and, in that capacity, Williams developed the concept of using imagery on the garage’s panel elements.

Kevin Williams is a partner in BSSW Architects, Inc., whose offices are located at 1500 Jackson Street #200, Fort Myers, FL 33901-2929 (left). It is the largest architectural firm headquartered in southwest Florida. Its reputation has been built on innovation and performance, backed by consideration of each project’s surroundings and respect for client budgets and schedules. Williams and BSSW had been selected as architects for the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage and, in that capacity, Williams developed the concept of using imagery on the garage’s panel elements.

Fast Facts

Parallel Park received the Americans for the Arts Public Art Network 2011 Year in Review Award. It was selected by curators Gail Goldman, Kendal Henry and Richard Turner out of 430 projects submitted by public art programs and artists nationwide.

Parallel Park received the Americans for the Arts Public Art Network 2011 Year in Review Award. It was selected by curators Gail Goldman, Kendal Henry and Richard Turner out of 430 projects submitted by public art programs and artists nationwide. States the artist: “My desire is to transform the perimeter of the structure into a progression of changing images and colorful patterns: both key elements of my paintings and drawings. These images and patterns recall architectural friezes, mosaics and frescoes of ancient, medieval and Renaissance artists, as well as works by early modern artists such as Synchroists and the Italian Futurists. It is my intent that Parallel Park will project a powerful signature identity.”

States the artist: “My desire is to transform the perimeter of the structure into a progression of changing images and colorful patterns: both key elements of my paintings and drawings. These images and patterns recall architectural friezes, mosaics and frescoes of ancient, medieval and Renaissance artists, as well as works by early modern artists such as Synchroists and the Italian Futurists. It is my intent that Parallel Park will project a powerful signature identity.”- States Barbara Hill of Art Consulting Incorporated (pictured to right conferring with former mayor Jim Humphrey): “Dintenfass’ work brings a unique visual vibrancy to this

architectural complex and represents an important moment in the field of public art in the United States. Research indicates that the use of this new technology to produce a massive exterior work of public art is the first of its kind in the nation. Parallel Park will surely stand as an iconic example of how a successful public art project can be funded by public and private sources and realized through an innovative collaborative process.”

architectural complex and represents an important moment in the field of public art in the United States. Research indicates that the use of this new technology to produce a massive exterior work of public art is the first of its kind in the nation. Parallel Park will surely stand as an iconic example of how a successful public art project can be funded by public and private sources and realized through an innovative collaborative process.” - Tobey Schneider was the parking garage’s builder.

- Mike Meece served as project manager.

- The printer was Jerry Banks, who is located in Hickory, North

Carolina, who counts NASCAR, Coca-Cola and Pepsi among his clients. “[They’re] also very particular about their colors.”

Carolina, who counts NASCAR, Coca-Cola and Pepsi among his clients. “[They’re] also very particular about their colors.” - The Kevlar weave contains quarter-inch size holes that are designed to enable the panels to withstand winds of up to 80 mph without ripping or tearing.

- The superstructure that supports the 23 panels and attaches them to the structure required 10,000 lineal feet of aluminum tubing.

- 30,000 connections anchor the tubing to the precast concrete. Each one had to be inspected by the precast manufacturing engineer.

- The building itself is 250 feel long by 140 feet wide.

- The project was completed in August of 2010; however, the official dedication and ribbon-cutting ceremony was held on December 9, 2010.

UPDATES AND DEVELOPMENTS

Dintenfass and Schlesinger to engage in gallery talk closing Ocular.Echo exhibition (06-11-17)

Parallel Park artist Marylyn Dintenfass and Natasha Schlesinger are participating in a Gallery Talk conversation from 3:00-4:30 p.m. on Saturday, June 17 at the Garrison Art Center in Garrison, New York. The discussion marks the close of Ocular.Echo, which has been on view at Garrison Art Center since May 27 and closes on Father’s Day, June 18.

Parallel Park artist Marylyn Dintenfass and Natasha Schlesinger are participating in a Gallery Talk conversation from 3:00-4:30 p.m. on Saturday, June 17 at the Garrison Art Center in Garrison, New York. The discussion marks the close of Ocular.Echo, which has been on view at Garrison Art Center since May 27 and closes on Father’s Day, June 18.

Ocular.Echo is comprised of a selection of paintings from a series inspired by the Hudson Valley in and around Garrison, New York. The circle is a key symbol  in Dintenfass’ work and the prism through which she considers her engagement with the visual variety of nature. Dintenfass uses overlays of color, shape, and transparency as expressions of change and metaphors for ecosystems of water, earth, air, flora and fauna.

in Dintenfass’ work and the prism through which she considers her engagement with the visual variety of nature. Dintenfass uses overlays of color, shape, and transparency as expressions of change and metaphors for ecosystems of water, earth, air, flora and fauna.

An art historian, Natasha Schlesinger is founder of ArtMuse, which provides art curation, consultation, and education to private clients and organizations. Schlesinger recently served as the curator of the Surrey Hotel and serves on the board of the Baryshnikov Arts Center. Schlesinger holds a Master’s degree in Decorative Arts and Design from the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Culture and Design. Her career includes both New York and London galleries and auction houses. She received the 25th Anniversary Future Women Leadership Award from ARTABLE.

An art historian, Natasha Schlesinger is founder of ArtMuse, which provides art curation, consultation, and education to private clients and organizations. Schlesinger recently served as the curator of the Surrey Hotel and serves on the board of the Baryshnikov Arts Center. Schlesinger holds a Master’s degree in Decorative Arts and Design from the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Culture and Design. Her career includes both New York and London galleries and auction houses. She received the 25th Anniversary Future Women Leadership Award from ARTABLE.

Marylyn Dintenfass’ work is found internationally in public collections, i ncluding: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain in Nice, France. This year, a new sculpture, Almost Like The Blues, was installed at LongHouse Reserve and Sculpture Garden as a part of their 2017 season. Exhibitions in 2011 and 2012 at Driscoll Babcock Galleries, New York, were selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows internationally by Modern Painters Magazine. Dintenfass has twice been a MacDowell Fellow and has received an Individual Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

ncluding: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain in Nice, France. This year, a new sculpture, Almost Like The Blues, was installed at LongHouse Reserve and Sculpture Garden as a part of their 2017 season. Exhibitions in 2011 and 2012 at Driscoll Babcock Galleries, New York, were selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows internationally by Modern Painters Magazine. Dintenfass has twice been a MacDowell Fellow and has received an Individual Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Founded in 1964, the Garrison Art Center brings outstanding art and studio ![artist[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/artist1.jpg) experiences to all ages of residents and visitors to Garrison and the Hudson Valley. Situated just steps from the Hudson River, the Center’s Riverside Galleries feature exhibitions including recent shows by Sean Scully, Judy Pfaff, Ivan Chermayeff and Don Nice as well as offering classes in painting, printmaking and sculpture.

experiences to all ages of residents and visitors to Garrison and the Hudson Valley. Situated just steps from the Hudson River, the Center’s Riverside Galleries feature exhibitions including recent shows by Sean Scully, Judy Pfaff, Ivan Chermayeff and Don Nice as well as offering classes in painting, printmaking and sculpture.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

With ‘Almost Like the Blues,’ abstract painter Marylyn Dintenfass dives into realm of steel sculpture (04-29-17)

Known locally for her 30,000-square-foot public art installation covering all four facades of the Lee County Justice Center in downtown Fort Myers, Marylyn Dintenfass has branched out now into the realm of steel sculpture. Her 30-foot-long outdoor installation, Almost Like the Blues, is the centerpiece of the Rites of Spring exhibition which opens today

Known locally for her 30,000-square-foot public art installation covering all four facades of the Lee County Justice Center in downtown Fort Myers, Marylyn Dintenfass has branched out now into the realm of steel sculpture. Her 30-foot-long outdoor installation, Almost Like the Blues, is the centerpiece of the Rites of Spring exhibition which opens today  at Longhouse Reserve in East Hampton, New York.

at Longhouse Reserve in East Hampton, New York.

Almost Like the Blues is a one of a series of freestanding, undulating steel sculptures by the abstract artist. In it, Dintenfass has captured the sensuous, transparent, hand-painted quality of her large oil paintings thanks to extremely detailed, high quality, and large-scale commercial digital printers.

The Rites of Spring exhibition marks the opening of the  2017 Longhouse season. In addition to the Dintenfass sculpture, new installations for this year include works by John Chamberlain, John Crawford, Judy Kensley McKie, Michael Mennin, Bernar Venet and Fred Wilson. Their works have been placed in the garden, together with installations by Buckminster Fuller, Willem de Kooning, Sol Lewitt and Yoko Ono.

2017 Longhouse season. In addition to the Dintenfass sculpture, new installations for this year include works by John Chamberlain, John Crawford, Judy Kensley McKie, Michael Mennin, Bernar Venet and Fred Wilson. Their works have been placed in the garden, together with installations by Buckminster Fuller, Willem de Kooning, Sol Lewitt and Yoko Ono.

Longhouse Reserve is a 16-acre sculpture garden in East Hampton Township’s Northwest Woods that was founded by legendary textile designer  Jack Lenore Larson. The exhibition continues through October 7.

Jack Lenore Larson. The exhibition continues through October 7.

Marylyn Dintenfass’ work is found in major public and private collections internationally, including: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.  Her 30,000 square foot 2010 Parallel Park installation in Fort Myers, Florida is one of the largest and most noteworthy of the last decade. Her work has been widely reviewed by Artinfo, ARTNews, Huffington Post and her 2011 and 2012 Babcock Galleries exhibitions were both selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows by

Her 30,000 square foot 2010 Parallel Park installation in Fort Myers, Florida is one of the largest and most noteworthy of the last decade. Her work has been widely reviewed by Artinfo, ARTNews, Huffington Post and her 2011 and 2012 Babcock Galleries exhibitions were both selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows by  Modern Painters.

Modern Painters.

Dintenfass has twice been a MacDowell Fellow and has received both an Individual Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts and two Project Grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her academic positions have included Visiting Professor at the National College of Art and  Design in Bergen and Oslo, Norway; Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, Israel; Sheridan College in Toronto, Canada and Hunter College in New York City. For ten years, she was a member of the faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Design in Bergen and Oslo, Norway; Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, Israel; Sheridan College in Toronto, Canada and Hunter College in New York City. For ten years, she was a member of the faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

Read here for more on the artist and Parallel Park.

________________________________________________________________________

New York gallery opens solo show of ‘Parallel Park’ artist’s ‘Ocular Echo’ series (05-27-17)

A new exhibit of work by renowned New York artist Marylyn Dintenfass goes on view at Riverside Galleries at Garrison Art Center in Garrison’s Landing, Garrison, New York today. Titled Ocular: Echo, the show presents a selection of paintings from a series inspired by the Hudson Valley in and around Garrison, New York.

A new exhibit of work by renowned New York artist Marylyn Dintenfass goes on view at Riverside Galleries at Garrison Art Center in Garrison’s Landing, Garrison, New York today. Titled Ocular: Echo, the show presents a selection of paintings from a series inspired by the Hudson Valley in and around Garrison, New York.

Dintenfass uses overlays of color, shape, and transparency as expressions of change and metaphors for ecosystems of water, earth, air, flora and fauna. In this, the circle is a key ![oculusfor_website0[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/oculusfor_website01-298x300.jpg) symbol and prism through which she considers her engagement with the visual variety of nature. Ocular Echo gives viewers the latest opportunity to consider these and other aspects of Dintenfass’ abstract expressionist work.

symbol and prism through which she considers her engagement with the visual variety of nature. Ocular Echo gives viewers the latest opportunity to consider these and other aspects of Dintenfass’ abstract expressionist work.

Founded in 1964, the Garrison Art Center brings outstanding art and studio experiences to all ages of residents and visitors to Garrison and the Hudson Valley. Situated just steps from the Hudson River, the Center’s Riverside Galleries feature exhibitions including recent shows by Sean Scully, Judy Pfaff, Ivan ![Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-4-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-4-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches1-300x300.jpg) Chermayeff and Don Nice as well as offering classes in painting, printmaking and sculpture.

Chermayeff and Don Nice as well as offering classes in painting, printmaking and sculpture.

Marylyn Dintenfass’ work is found in major public and private collections internationally, including: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Her 30,000 square foot 2010 Parallel Park installation in Fort Myers, Florida is one of the largest and most noteworthy of the last decade. Her work has been widely  reviewed by Artinfo, ARTNews, Huffington Post and her 2011 and 2012 Babcock Galleries exhibitions were both selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows by Modern Painters.

reviewed by Artinfo, ARTNews, Huffington Post and her 2011 and 2012 Babcock Galleries exhibitions were both selected as one of the year’s top 100 shows by Modern Painters.

Dintenfass has twice been a MacDowell Fellow and has received both ![artist[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/artist1.jpg) an Individual Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts and two Project Grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her academic positions have included Visiting Professor at the National College of Art and Design in Bergen and Oslo, Norway; Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, Israel; Sheridan College in Toronto, Canada and Hunter College in New York City. For ten years, she was a member of the faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

an Individual Artist Fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts and two Project Grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her academic positions have included Visiting Professor at the National College of Art and Design in Bergen and Oslo, Norway; Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, Israel; Sheridan College in Toronto, Canada and Hunter College in New York City. For ten years, she was a member of the faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City.

The exhibition runs May 27-June 18, 2017.

_______________________________________________________

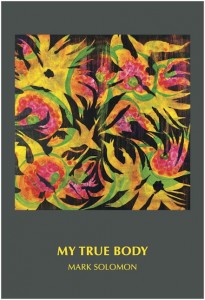

Marylyn Dintenfass painting chosen for cover of new book (08-25-16)

Marylyn Dintenfass’ painting, Came Upon a Burning Bush, appears on the cover of a new book by Mark Soloman titled My True Body. Soloman received his B.A. in English Literature from Columbia College in 1962 and worked toward an M.A. in 17th Century English Poetry at Columbia Graduate Faculties. His first published poems appeared in Broadway Boogie in 1973. In January 1993, he received an MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College and since then has published in TriQuarterly, Hanging Loose, BOMB, The Marlboro Review, The Beloit Poetry Journal, Southern Poetry Review, and other periodicals and anthologies. My True Body is his first full-length collection.

Marylyn Dintenfass’ painting, Came Upon a Burning Bush, appears on the cover of a new book by Mark Soloman titled My True Body. Soloman received his B.A. in English Literature from Columbia College in 1962 and worked toward an M.A. in 17th Century English Poetry at Columbia Graduate Faculties. His first published poems appeared in Broadway Boogie in 1973. In January 1993, he received an MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College and since then has published in TriQuarterly, Hanging Loose, BOMB, The Marlboro Review, The Beloit Poetry Journal, Southern Poetry Review, and other periodicals and anthologies. My True Body is his first full-length collection.

Came Upon a Burning Bush is from Dintenfass’ 2012 Drop Dead Gorgeous exhibition.

___________________

2015 Articles and Links.

Art News’ critic Benjamin Genocchio reviews ‘Oculus’ (09-18-15)

Art Southwest Florida reported previously that Manhattan’s Driscoll Babcock Gallery was opening a new exhibit of Parallel Park artist Marylyn Dintenfass work under the title of Oculus. Art critic Benjamin Genocchio recently reviewed the show for Art News Magazine.

Art Southwest Florida reported previously that Manhattan’s Driscoll Babcock Gallery was opening a new exhibit of Parallel Park artist Marylyn Dintenfass work under the title of Oculus. Art critic Benjamin Genocchio recently reviewed the show for Art News Magazine.

Genocchio was touched by Dintenfass’ symbolic contemporary artworks, pointing out that the artist has reached a stage in her life and career that affords her “a certain freedom to experiment with materials, like interference paint (a  commercial-grade pigment creating iridescent qualities that also enables subtle variation and manipulation of a painted surface), but also the distance to stand back from her art, and herself, to connect with larger, mysterious forces that swirl within and around us.”

commercial-grade pigment creating iridescent qualities that also enables subtle variation and manipulation of a painted surface), but also the distance to stand back from her art, and herself, to connect with larger, mysterious forces that swirl within and around us.”

Southwest Florida visitors and residents  discovered this aspect of Dintenfass’ art in connection with her 30,000-square-foot public art installation on the four facades of the 5-story Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage. While the imagery incorporated into her twenty-three 33 x 22 foot abstract expressionist panels include tires, dashboard instrumentation and headlights associated with the muscle cars of her youth,

discovered this aspect of Dintenfass’ art in connection with her 30,000-square-foot public art installation on the four facades of the 5-story Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage. While the imagery incorporated into her twenty-three 33 x 22 foot abstract expressionist panels include tires, dashboard instrumentation and headlights associated with the muscle cars of her youth,  they are individually and collectively symbols of the freedom that cars give each of us to come and go as and wherever we please. And that freedom changed the dynamics of our lives. Where before the invention of the automobile, people lived their entire lives in the neighborhoods of their birth, today it is the rare individual who remains in the town or even the state of their birth.

they are individually and collectively symbols of the freedom that cars give each of us to come and go as and wherever we please. And that freedom changed the dynamics of our lives. Where before the invention of the automobile, people lived their entire lives in the neighborhoods of their birth, today it is the rare individual who remains in the town or even the state of their birth.

Genocchio posits that Dintenfass’ new show, Oculus, is about mortality. “Each [of the dozen 77-![oculusfor_website0[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/oculusfor_website01-298x300.jpg) square-inch paintings included in the show] is a life cycle, a circle of life, with its ebbs and flows, its ups and downs, its highs and lows and its eventual disappearance into nothingness. You can see this clearly in those works which look and feel very molecular, with undulating swirls that are almost liquid in design, and others that resemble the grain that’s found on the surface of wood.”

square-inch paintings included in the show] is a life cycle, a circle of life, with its ebbs and flows, its ups and downs, its highs and lows and its eventual disappearance into nothingness. You can see this clearly in those works which look and feel very molecular, with undulating swirls that are almost liquid in design, and others that resemble the grain that’s found on the surface of wood.”

This concept was also captured by the late Robert Sindorf in his chiseled granite art piece, Wheel of Life, that stands west of the intersection of Main  and Monroe in the downtown Fort Myers River District. While the sculpture lacks the elegance and depth of the paintings in Oculus, the symbolism is similar. And that’s why many artists and collectors are drawn to abstract art. Yes, technical proficiency is still necessary, but the genre frees practitioners to explore deeper psychological, philosophical and metaphysical issues and concerns.

and Monroe in the downtown Fort Myers River District. While the sculpture lacks the elegance and depth of the paintings in Oculus, the symbolism is similar. And that’s why many artists and collectors are drawn to abstract art. Yes, technical proficiency is still necessary, but the genre frees practitioners to explore deeper psychological, philosophical and metaphysical issues and concerns.

Or as Genocchio concludes about Oculus’ visceral, organic, life-and-death subject matter, “Rarely does visual beauty pack such a serious existential punch.”

_____________________________________________________

Exhibition of new work by ‘Parallel Park’ artist Marylyn Dintenfass to open in New York City (09-05-15)

![Dintenfass_OCULUS_copy0[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Dintenfass_OCULUS_copy01-300x180.jpg) Manhattan’s Driscoll Babcock Galleries will present the latest body of paintings on canvas and paper by Parallel Park abstract artist Marylyn Dintenfass. Titled Oculus, this is the artist’s ninth one-person show in New York City and her fifth at Driscoll Babcock.

Manhattan’s Driscoll Babcock Galleries will present the latest body of paintings on canvas and paper by Parallel Park abstract artist Marylyn Dintenfass. Titled Oculus, this is the artist’s ninth one-person show in New York City and her fifth at Driscoll Babcock.

The circle motif has been one of the constants ![oculusfor_website0[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/oculusfor_website01-298x300.jpg) in the visual lexicon that Dintenfass has employed throughout her work. Evoking a wide range of mathematical, historical and philosophical references—from cellular microcosms to celestial macrocosms—Dintenfass has sustained a perceptive investigation of this iconic, essential shape. But now, her methodical, process-oriented exercise of exploring the expressive and technical possibilities of circles has now grown into a meditative celebration of the architectural oculus.

in the visual lexicon that Dintenfass has employed throughout her work. Evoking a wide range of mathematical, historical and philosophical references—from cellular microcosms to celestial macrocosms—Dintenfass has sustained a perceptive investigation of this iconic, essential shape. But now, her methodical, process-oriented exercise of exploring the expressive and technical possibilities of circles has now grown into a meditative celebration of the architectural oculus. ![20150723165638-Dintenfass_SPREE[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/20150723165638-Dintenfass_SPREE1-295x300.jpg) The work began with a concentrated series of 15-inch square paintings and over time led to ever larger works that have culminated in a series of 77-inch square paintings. Dintenfass found these paintings to be a great source of energy at the same time that they expanded her personal emblematic identification.

The work began with a concentrated series of 15-inch square paintings and over time led to ever larger works that have culminated in a series of 77-inch square paintings. Dintenfass found these paintings to be a great source of energy at the same time that they expanded her personal emblematic identification.

Whereas some of her oculi are made with strong gestural marks, revealing the presence of Dintenfass’ hand, others make use of a highly controlled, hard-edge matrix derived from ![Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-18-2015-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-18-2015-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches1-300x300.jpg) ring-like templates of her own design. The tension between these two modes, organic and mathematical, becomes a critical element of the series, playing against each other’s similarities and differences.

ring-like templates of her own design. The tension between these two modes, organic and mathematical, becomes a critical element of the series, playing against each other’s similarities and differences.

Dintenfass’ Oculus works are also influenced by her concerns for architectural space and scale. The oculus (Latin for “eye”) originated in antiquity as a circular opening, often at the top of a dome. The oculus allowed a focused beam of natural light to illuminate a building’s interior. This illumination changed with the hour, weather conditions and ![Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-31-2015-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-31-2015-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches1-300x300.jpg) season. Thus, even though the “opening” remained constant, its interaction with and control of light, and the fact that one can see both into and out of an oculus, is full of provocative dichotomies, meanings and visual possibilities. This is one source of Dintenfass’ fascination with the conceptual possibilities of oculi; of the “palpable, full body impact” of experiencing the oculus’ circular shaft of light animating monumental temples, churches and other ancient buildings she has encountered in Italy and Turkey, as well as

season. Thus, even though the “opening” remained constant, its interaction with and control of light, and the fact that one can see both into and out of an oculus, is full of provocative dichotomies, meanings and visual possibilities. This is one source of Dintenfass’ fascination with the conceptual possibilities of oculi; of the “palpable, full body impact” of experiencing the oculus’ circular shaft of light animating monumental temples, churches and other ancient buildings she has encountered in Italy and Turkey, as well as ![Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-4-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches[1]](http://www.artswfl.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Marylyn-Dintenfass-Oculus-4-Oil-on-paper-15-x-15-inches1-300x300.jpg) more recent encounters including James Turrell’s Roden Crater.

more recent encounters including James Turrell’s Roden Crater.

Here, the Oculus works—enigmatic, hypnotic and meditative—bring together and fully embody Dintenfass’ interest in the phenomenological impact and meaning of the physical and conceptual Oculus.

The effects of illumination that changes with the hour, weather conditions and season also lies at the root of Dintenfass’ monumental public art  piece, Parallel Park. Dedicated on December 9, 2010, Parallel Park is a site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation. It consists of 23 open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels that have been attached to the exterior of the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage by aluminum tubes. Each panel stands 33 feet tall by 22 feet wide and the images change right before

piece, Parallel Park. Dedicated on December 9, 2010, Parallel Park is a site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation. It consists of 23 open-weave Kevlar and fiberglass fabric panels that have been attached to the exterior of the Lee County Justice Center Parking Garage by aluminum tubes. Each panel stands 33 feet tall by 22 feet wide and the images change right before  the viewer’s eyes as the sun carves its daily arc and clouds scurry across the bright blue Florida sky. Not only do the panels engage the viewer kinetically, they tell a story. The characters in Dintenfass’ novel are color, shape, scale and pattern, and each side of the building represents a new chapter. But by the time you circle the building, the sun and clouds have changed position, and you are presented with four new chapters in this never-ending story.

the viewer’s eyes as the sun carves its daily arc and clouds scurry across the bright blue Florida sky. Not only do the panels engage the viewer kinetically, they tell a story. The characters in Dintenfass’ novel are color, shape, scale and pattern, and each side of the building represents a new chapter. But by the time you circle the building, the sun and clouds have changed position, and you are presented with four new chapters in this never-ending story.

__________________________________________________________

New Dintenfass solo show explores expressive qualities and technical possibilities of circles (07-24-15)

Driscoll Babcock Galleries in New York will be presenting a new series of work in September by abstract and monumental artist Marylyn Dintenfass. It is called Oculus, and is a collection of paintings on canvas and paper that explores the expressive and technical possibilities of circles.

Driscoll Babcock Galleries in New York will be presenting a new series of work in September by abstract and monumental artist Marylyn Dintenfass. It is called Oculus, and is a collection of paintings on canvas and paper that explores the expressive and technical possibilities of circles.

This work began with a concentrated series of 15-inch square paintings that led, over time, to ever larger works that ultimately culminated in a series of 77-inch square paintings that Dintenfass found to be a great source of energy while simultaneously expanding her personal emblematic identification.

“The circle motif has been one of the constants in the visual lexicon that Dintenfass has employed throughout her work,” notes Driscoll Babcock. “Evoking a wide range of mathematical, historical and philosophical references—from cellular microcosms to celestial macrocosms—Dintenfass has sustained a perceptive investigation of this iconic, essential shape. Whereas some of her oculi are made with strong gestural marks, revealing the presence of Dintenfass’ hand, others make use of a highly controlled, hard-edge matrix derived from

“The circle motif has been one of the constants in the visual lexicon that Dintenfass has employed throughout her work,” notes Driscoll Babcock. “Evoking a wide range of mathematical, historical and philosophical references—from cellular microcosms to celestial macrocosms—Dintenfass has sustained a perceptive investigation of this iconic, essential shape. Whereas some of her oculi are made with strong gestural marks, revealing the presence of Dintenfass’ hand, others make use of a highly controlled, hard-edge matrix derived from  ring-like templates of her own design. The tension between these two modes, organic and mathematical, becomes a critical element of the series, playing against each other’s similarities and differences.”

ring-like templates of her own design. The tension between these two modes, organic and mathematical, becomes a critical element of the series, playing against each other’s similarities and differences.”

Dintenfass’ Oculus works are also influenced by  her concerns for architectural space and scale. The oculus (Latin for “eye”) originated in antiquity as a circular opening, often at the top of a dome. The oculus allowed a focused beam of natural light to illuminate a building’s interior. This illumination changed with the hour, weather conditions and season. Thus, even though the “opening” remained

her concerns for architectural space and scale. The oculus (Latin for “eye”) originated in antiquity as a circular opening, often at the top of a dome. The oculus allowed a focused beam of natural light to illuminate a building’s interior. This illumination changed with the hour, weather conditions and season. Thus, even though the “opening” remained  constant, its interaction with and control of light, and the fact that one can see both into and out of an oculus, is full of provocative dichotomies, meanings and visual possibilities.

constant, its interaction with and control of light, and the fact that one can see both into and out of an oculus, is full of provocative dichotomies, meanings and visual possibilities.

“This is one source of Dintenfass’ fascination with the conceptual possibilities of oculi; of the ‘palpable, full body impact’ of experiencing the oculus’ circular shaft of light animating monumental temples, churches and other ancient buildings she has encountered in Italy and Turkey, as well as more  recent encounters including James Turrell’s Roden Crater,” Driscoll Babcock continues.

recent encounters including James Turrell’s Roden Crater,” Driscoll Babcock continues.

In this new exhibition, Dintenfass’ Oculus works—enigmatic, hypnotic and meditative—bring together and fully embody Dintenfass’ interest in the phenomenological impact and meaning of the physical and conceptual Oculus.

This will be the artist’s ninth one-person show in New York City, and her fifth at Driscoll Babcock. Local art enthusiasts and collectors will draw parallels to the tire and dashboard instrument shaped circles and spheres that denoted her earlier work and which she used in the imagery employed in Parallel Park, the site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation on the five-story Lee

This will be the artist’s ninth one-person show in New York City, and her fifth at Driscoll Babcock. Local art enthusiasts and collectors will draw parallels to the tire and dashboard instrument shaped circles and spheres that denoted her earlier work and which she used in the imagery employed in Parallel Park, the site-specific 30,000 square foot outdoor art installation on the five-story Lee  County Justice Center Parking Garage. The a new series of paintings celebrating the circle motif will be on display at Driscoll Babcock Galleries from September 10 through October 24, with an opening reception on Thursday, September 10, from 6-8 p.m. The gallery is located at 525 West 25 Street, NYC.

County Justice Center Parking Garage. The a new series of paintings celebrating the circle motif will be on display at Driscoll Babcock Galleries from September 10 through October 24, with an opening reception on Thursday, September 10, from 6-8 p.m. The gallery is located at 525 West 25 Street, NYC.

Driscoll Babcock Galleries is New York’s oldest art  gallery and has represented important contemporary artists for more than 160 years. The Gallery’s strong focus on American Masters includes Asher B. Durand, Thomas Cole, John F. Kensett, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Charles Sheeler, Edwin Dickinson, and Stuart Davis. This program is complemented by an active pursuit of important

gallery and has represented important contemporary artists for more than 160 years. The Gallery’s strong focus on American Masters includes Asher B. Durand, Thomas Cole, John F. Kensett, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Charles Sheeler, Edwin Dickinson, and Stuart Davis. This program is complemented by an active pursuit of important  works by Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, John Graham, Mark Tobey, Ben Nicholson, Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Jules Olitski, among many others.

works by Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, John Graham, Mark Tobey, Ben Nicholson, Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Jules Olitski, among many others.

The Gallery’s current roster of internationally recognized artists includes Harriet Bart, Wafaa  Bilal, Margaret Bowland, Marylyn Dintenfass, and Jenny Morgan, with additional works by Deborah Butterfield, Chuck Close, Hans Coper, Anselm Kiefer, Mr., and James Rosenquist.

Bilal, Margaret Bowland, Marylyn Dintenfass, and Jenny Morgan, with additional works by Deborah Butterfield, Chuck Close, Hans Coper, Anselm Kiefer, Mr., and James Rosenquist.

Major private, corporate, and museum collections across the country have relied on Driscoll Babcock’s exceptional expertise in locating and  acquiring iconic works of art. The Gallery remains committed to building entire collections in the tradition of integrating great and recognized masterworks of the past with today’s most noteworthy and durable achievements.

acquiring iconic works of art. The Gallery remains committed to building entire collections in the tradition of integrating great and recognized masterworks of the past with today’s most noteworthy and durable achievements.

Dr. John Driscoll, an internationally known scholar with a specialized background in American Modernism and the Hudson River School, as well as French Impressionism, heads a staff noted for its advanced academic training, museum experience, and sound market knowledge.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.