Louise Nevelson’s Dawn’s Forest

Dawn’s Forest was Louise Nevelson’s last, largest and most complex work. She completed it a less than two years before she died of cancer on April 17, 1988 at the age of 88.

Dawn’s Forest was Louise Nevelson’s last, largest and most complex work. She completed it a less than two years before she died of cancer on April 17, 1988 at the age of 88.

The balsa and pine plywood sculptural environment consists of several components:

The focal point is a free-standing assemblage 22′ tall by 54′ long and 6′ deep that contains a central squared arch with seven flanking columns

The focal point is a free-standing assemblage 22′ tall by 54′ long and 6′ deep that contains a central squared arch with seven flanking columns- It is complemented by an 11′ tall by 31′ 8″ long by 3′ deep wall hanging that Nevelson designed to tower over the free-standing central component.

- The assemblage also features 3 separate hanging elements which are 10′ 4″, 19′ and 9′ 6″ tall respectively.

- There are also two separate 25′ tall free-standing towers.

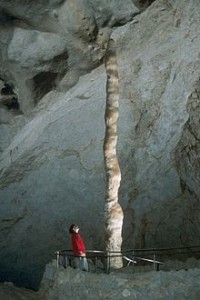

In typical Nevelson form, the environment is monochromatic. With components jutting in various lengths and widths from the floor and descending from the ceiling overhead, the all-white environment conjures images of a vast subterranean forest of calcite white stalagmites and stalactites. In fact, Dawn’s Forest’s two 25-foot towers are reminiscent of two majestic dripstone spires found in the Carlsbad Caverns, The Witch’s Finger (left) and the stout pillar in the Hall of Giants.

In typical Nevelson form, the environment is monochromatic. With components jutting in various lengths and widths from the floor and descending from the ceiling overhead, the all-white environment conjures images of a vast subterranean forest of calcite white stalagmites and stalactites. In fact, Dawn’s Forest’s two 25-foot towers are reminiscent of two majestic dripstone spires found in the Carlsbad Caverns, The Witch’s Finger (left) and the stout pillar in the Hall of Giants.

Nevelson first conceived and envisioned the project in the 1970s, but she did not give impetus to the final design until she received a commission for the assemblage from paper product manufacturer Georiga Pacific and insurance giant Metropolitan Life in 1985. As was her practice at this late stage in her art career, Nevelson recycled parts of previous works, re-collaging them, as it were, into the new design. For example, the large central column of Dawn’s Forest dates back to 1971, with several other elements having been completed in 1976.

Nevelson first conceived and envisioned the project in the 1970s, but she did not give impetus to the final design until she received a commission for the assemblage from paper product manufacturer Georiga Pacific and insurance giant Metropolitan Life in 1985. As was her practice at this late stage in her art career, Nevelson recycled parts of previous works, re-collaging them, as it were, into the new design. For example, the large central column of Dawn’s Forest dates back to 1971, with several other elements having been completed in 1976.

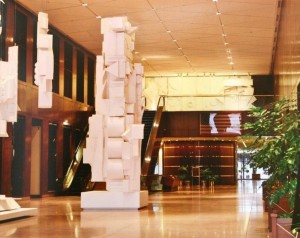

The completed work was installed under Nevelson’s watchful eye the following year in the dark panelled lobby of Georgia Pacific and MetLife’s headquarters in Atlanta (left). The grouping was displayed there until 2010, when it was donated to the Patty & Jay Baker Naples Museum of Art. It arrived in Naples on three trucks in May of that year, and was placed on display in the museum’s grand atrium, called the Figge Conservatory (right).

The completed work was installed under Nevelson’s watchful eye the following year in the dark panelled lobby of Georgia Pacific and MetLife’s headquarters in Atlanta (left). The grouping was displayed there until 2010, when it was donated to the Patty & Jay Baker Naples Museum of Art. It arrived in Naples on three trucks in May of that year, and was placed on display in the museum’s grand atrium, called the Figge Conservatory (right).

It was disassembled and moved to the Southwest Florida International Airport in November of 2012, where it is on exhibit for two years pursuant to the Art in Flight program that the Lee County Alliance for the Arts operates in partnership with the Lee County Port Authority. The loan has been made through an interlocal agreement between the Alliance, the Port Authority and the Patty & Jay Baker Naples Museum of Art.

It was disassembled and moved to the Southwest Florida International Airport in November of 2012, where it is on exhibit for two years pursuant to the Art in Flight program that the Lee County Alliance for the Arts operates in partnership with the Lee County Port Authority. The loan has been made through an interlocal agreement between the Alliance, the Port Authority and the Patty & Jay Baker Naples Museum of Art.

“When visitors and residents arrive at the airport, we want art and culture to be at the front of their mind,” Phil president and CEO Kathleen van Bergen remarks. More than 7 million people passengers depart from and arrive at Southwest Florida International Airport annually, and counting families and friends who greet them together with employees, vendors and delivery personnel, more than 12 million people pass through RSW’s terminal each year. Dawn’s Forest will assuredly create a lasting first impression of their visit to southwest Florida.

“When visitors and residents arrive at the airport, we want art and culture to be at the front of their mind,” Phil president and CEO Kathleen van Bergen remarks. More than 7 million people passengers depart from and arrive at Southwest Florida International Airport annually, and counting families and friends who greet them together with employees, vendors and delivery personnel, more than 12 million people pass through RSW’s terminal each year. Dawn’s Forest will assuredly create a lasting first impression of their visit to southwest Florida.

The sculpture’s new residence is the atrium between Concourses B and C, where a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows floods the environment with incongruous organic light. Because neither the ceiling trusses nor glass walls could support the weight of the wall relief, it has been placed

The sculpture’s new residence is the atrium between Concourses B and C, where a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows floods the environment with incongruous organic light. Because neither the ceiling trusses nor glass walls could support the weight of the wall relief, it has been placed  on the ground instead of being mounted above Nevelson’s free-standing central assemblage. In a concession to airport functionality, both the floor assemblage and the wall relief are eclipsed by an immovable digital flight status console. Four massive potted palms that are presumably too heavy to move and scores of brown wood chairs also detract from the installation’s aesthetics. The Forest is impressive notwithstanding, and its pre-security location enables families and friends to immerse themselves in the sculptural environment while waiting to greet inbound passengers or after sending off departing air travellers.

on the ground instead of being mounted above Nevelson’s free-standing central assemblage. In a concession to airport functionality, both the floor assemblage and the wall relief are eclipsed by an immovable digital flight status console. Four massive potted palms that are presumably too heavy to move and scores of brown wood chairs also detract from the installation’s aesthetics. The Forest is impressive notwithstanding, and its pre-security location enables families and friends to immerse themselves in the sculptural environment while waiting to greet inbound passengers or after sending off departing air travellers.

About Louise Nevelson

Louise Nevelson is considered one of the most important American sculptors of the twentieth century. Although she earned no steady income from her work until she was in her sixties, the notoriety and celebrity she achieved during the last third of her life has endured long after her death. One of the world’s most celebrated female artists in her time, her work continues to inspire contemporary sculptors today and is represented in hundreds of museums and private collections around the world.

Louise Nevelson is considered one of the most important American sculptors of the twentieth century. Although she earned no steady income from her work until she was in her sixties, the notoriety and celebrity she achieved during the last third of her life has endured long after her death. One of the world’s most celebrated female artists in her time, her work continues to inspire contemporary sculptors today and is represented in hundreds of museums and private collections around the world.

She was born Leah Berliawsky to a Russian junk dealer, but her father resettled the family in Rockland, Maine in 1905. Young Leah grew up playing with scraps of wood scavenged from her father’s lumber yard. Feelings of isolation and displacement prompted her to turn to art for solace, and by 10, she had decided to become a professional sculptor.

“I never made friends,” she said later, ”because I didn’t intend to stay in Rockland, and I didn’t want anything to tie me down.”

Her career as a sculptor did not really get under way until 1920, following her marriage to a wealthy ship owner by the name of Charles Nevelson, who moved her to New York. Soon after, Louise enrolled at the Art Students League, and she went on to study with Chaim Gross, Georg Grosz and Hans Hoffman, the latter in both Germany and New York (after Hoffman fled the Nazi ban on modernism in the early ’30s). She even assisted Diego Rivera while he was preparing his murals for Rockefeller Center. Calling upon her childhood experiences in her father’s junk or lumbar yard, she scavenged wood during this time from the streets near her home on Spring Street in Little Italy, converting it into memorable works of art. She also became pregnant, giving birth to a son, Myron (later known as Mike) in 1922. The marriage did not work out, and the Nevelsons separated in the early 1930s and divorced officially in 1941.

After working in relative anonymity for more than two decades, the sculptress decided following her divorce that it was time to change that equation. So she approached Cologne art dealer Karl Nierendorf, who had never before exhibited an American artist in his prestigious New York gallery. She was so convincing that not only did Nierendorf grant her the exhibition, he represented her until his death six years later in 1947.

After her solo exhibition, Nevelson continued to develop her signature style, which involved, as before, with filling boxes with discarded wood and found objects she culled from neighborhood streets. She painted both the boxes and the objects black and constructed abstract compositions within each box, stacking them to form sculptural walls and environments through which spectators could walk.

Nevelson finally created the buzz she deserved in a 1958 exhibition of her all-black environments. A year later, her room-size, all white environment, Dawn’s Wedding Feast, was included in Sixteen Americans, a prestigious 1959-1960 group show at The Museum of Modern Art that also included future icons Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns (with whom Nevelson became lifelong friends). By the time the exhibition closed, Nevelson had become recognized as a creative force in the realm of modern sculpture

Nevelson’s reputation soared during the 1960s. She represented the United States at the Venice Biennial, had her first important retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and became the first woman to be elected National President of Artists’ Equity. Sought after for her large-scale sculptural works, Nevelson also became one of the first artists, and the only woman, to become a central figure in the burgeoning public art revival of the 1960s.

She created more than 22 public commissions in her lifetime. Some of her more renowned public artworks include Sky Gate – New York (1978) at the World Trade Center (destroyed in 2001); Shadows and Flags (1977) in lower Manhattan; Chapel of the Good Shepherd (1977) at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in New York; Celebration (1976-77) at Pepsico World Headquarters, Purchase, NY; Bicentennial Dawn (1976) at Bryne-Greene Federal Courthouse, Philadelphia; Night Presence IV (1972) on Park Avenue at 92nd Street; and Atmosphere and Environment X (1969) at Princeton University.

While Nevelson continued to execute wood constructions during this time, she also began introducing welded vertical shapes that incorporated such new materials as black lucite, aluminum and magnesium, as in Atmosphere and Environment. In Environment, too, she achieved open, free-standing structures as concerned with volume as they are with mass. As her work evolved, she came to prefer compositions with fewer elements and more rigidly-controlled relief space.

During the mid-1970s, Nevelson utilized cast paper in pieces such as Dawn’s Presence (1976). In the early 1980s and mid-1980s, she worked with detailed PHSColograms in Keeping Time with Fashion (1983) and painted wood in Mirror Shadow XI (1985) and Dawn’s Forest (1986).

Over the course of her career, Nevelson received six honorary doctorates and exhibited her work in both Europe and the United States.

Her artwork evolved from tabletop pieces to human-scale columns to room-size walls and environments and finally to monumental public art. Remembered for her natural abstract sculptures, her death in 1988 marked a significant loss to the world of art.

[Based in part on biography prepared by the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.]

Location.

- Dawn’s Forest is located in the pre-security atrium between Concourses B and C at Southwest Florida International Airport.

- Its address is 11000 Terminal Access Road, Fort Myers, FL 33913.

- It is located at Latitude N 26° 31′ 41.1476″ and Longitude:W 81° 45′ 14.3964″.

Fast Facts.

The Phil’s founder and original President and CEO, Myra Janco Daniels, arranged for donation of Dawn’s Forest to the Naples Museum of Art in 2010.

The Phil’s founder and original President and CEO, Myra Janco Daniels, arranged for donation of Dawn’s Forest to the Naples Museum of Art in 2010.- She heard that Georgia Pacific and Met Life were de-accessioning the piece from Naples art collector and museum friend Robert Edwards and immediately flew to Atlanta to make her pitch for the piece.

- Georgia Pacific and Met Life had decided to part with the piece in order to change the design of the lobby of their corporate headquarters.

- Three trucks brought the installation to Naples in late May of 2010. Most of the pieces fit through the museum’s lobby doors, although one window had to be removed to accommodate others.

Dawn’s Forest was installed in the museum’s grand atrium, known as the Figge Conservatory. To make room for the massive piece, Dale Chihuly’s two-story “Red Chandelier” had to be moved to the Philharmonic Center, under the lights in the west gallery balcony well.

Dawn’s Forest was installed in the museum’s grand atrium, known as the Figge Conservatory. To make room for the massive piece, Dale Chihuly’s two-story “Red Chandelier” had to be moved to the Philharmonic Center, under the lights in the west gallery balcony well.- The sculpture’s original white matte finish was repainted in latex in 2010 when it was moved from Atlanta to Naples to cover normal wear and tear.

- If Nevelson had in mind a subterranean forest of dripstones, her hanging stalactite-reminiscent trio could have been patterned after those found in the White Chamber in the Jeita Grotto’s upper cavern in Lebanon which contains an 8.2 m (27 ft) stalactite which is claimed to be the longest stalactite in the world.

Related Articles.

- Nevelson became iconic American sculptor by sheer force of indomitable will (11-25-12)

- Success did not come easily or early for iconic sculptor Louise Nevelson (11-24-12)

- ‘Dawn’s Forest’ converts Southwest Florida International into art port (11-19-12)

- ‘Dawn’s Forest’ was Louise Nevelson’s last, largest and most complex environment (09-29-12)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.