The Harborside Collection

The Harborside Event Center is home to seven busts of local legends. Known as “The Harborside Collection,” these statues pay homage to Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs, Captain Francis Asbury Hendry, Thomas Alva Edison, Tootie McGregor Terry, Paul Laurence Dunbar, James D. Newton and Connie Mack. Each resides in its own alcove in the north Galleria that runs along the meeting rooms at the Event Center.

The Harborside Event Center is home to seven busts of local legends. Known as “The Harborside Collection,” these statues pay homage to Seminole Chief Billy Bowlegs, Captain Francis Asbury Hendry, Thomas Alva Edison, Tootie McGregor Terry, Paul Laurence Dunbar, James D. Newton and Connie Mack. Each resides in its own alcove in the north Galleria that runs along the meeting rooms at the Event Center.

The project was a joint venture between:

The project was a joint venture between:

- the Fort Myers Beautification Advisory Board, which commissioned the busts of Billy Bowlegs, Thomas Edison and Paul Dunbar;

- local appliance dealer and Greater Fort Myers Chamber of Commerce founder Wilbur C. “Bill” Smith, Jr., who financed Tootie McGregor and Connie Mack;

- the Hendry Family, which paid for F.A.’s bust; and

- Eric McNabb, a friend and business partner of James D. Newton.

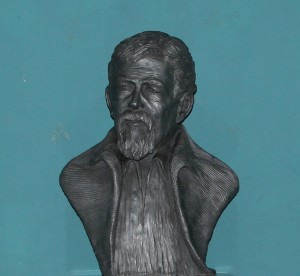

All but Billy Bowlegs were cast by local sculptor D.J. Wilkins; the great Seminole chief was sculpted in Wilkins Studio by Greg Biolchini. Each bust is a cold cast composite. Billy Bowlegs is made of dark red bronze; Hendry is aluminum; Edison is powdered bronze with a little bit of brass thrown in to prevent the sculpture from darkening too much; Dunbar is 30 percent brass and 70 percent powdered chestnut bronze; with Tootie McGregor being a combination of white cast marble with pink dye and a hardening agent added to the portion that represents her dress. Each bust stands 25 inches tall, except Edison’s, which is 27 inches in height. The busts are displayed on Corian marble pedestals that were paid for by Bill Smith’s wife, Mary Alice Fohl Smith.

All but Billy Bowlegs were cast by local sculptor D.J. Wilkins; the great Seminole chief was sculpted in Wilkins Studio by Greg Biolchini. Each bust is a cold cast composite. Billy Bowlegs is made of dark red bronze; Hendry is aluminum; Edison is powdered bronze with a little bit of brass thrown in to prevent the sculpture from darkening too much; Dunbar is 30 percent brass and 70 percent powdered chestnut bronze; with Tootie McGregor being a combination of white cast marble with pink dye and a hardening agent added to the portion that represents her dress. Each bust stands 25 inches tall, except Edison’s, which is 27 inches in height. The busts are displayed on Corian marble pedestals that were paid for by Bill Smith’s wife, Mary Alice Fohl Smith.

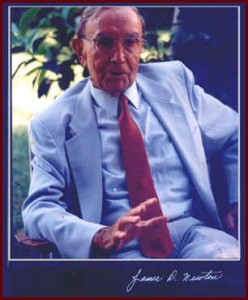

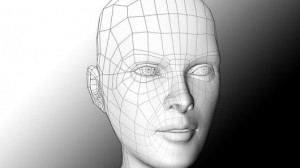

By the time Wilkins was commissioned to create the Harborside Collection, all but James Newton (right) had died. “So to make the cast for each bust, I had to work from black-and-white photographs,” Wilkins relates. Ideally, Wilkins needed photographs showing the front, back and both profiles of each subject, “and they had to be from the same age bracket, typically their mid to late fifties.” From the photo array, Wilkins created a map or grid that enabled him to convert two-dimensional images into a three-dimensional sculpture … more than 20 years before researchers at Florida Atlantic University developed a computer algorithm that is capable of creating 3D models of faces based on 2D images.

By the time Wilkins was commissioned to create the Harborside Collection, all but James Newton (right) had died. “So to make the cast for each bust, I had to work from black-and-white photographs,” Wilkins relates. Ideally, Wilkins needed photographs showing the front, back and both profiles of each subject, “and they had to be from the same age bracket, typically their mid to late fifties.” From the photo array, Wilkins created a map or grid that enabled him to convert two-dimensional images into a three-dimensional sculpture … more than 20 years before researchers at Florida Atlantic University developed a computer algorithm that is capable of creating 3D models of faces based on 2D images.

His trickiest subject turned out to be Tootie McGregor Terry. “I could only find one little black-and-white photo and it was downright unattractive (left),” Wilkins recalls. “Since I couldn’t express beauty, I decided to portray the dignity for which she was known. Some years later, one of her grand nieces came to visit. She looked me up to tell me that even though I’d never met her great-aunt, I’d nailed her likeness,” Wilkins adds with deserved pride and satisfaction.

His trickiest subject turned out to be Tootie McGregor Terry. “I could only find one little black-and-white photo and it was downright unattractive (left),” Wilkins recalls. “Since I couldn’t express beauty, I decided to portray the dignity for which she was known. Some years later, one of her grand nieces came to visit. She looked me up to tell me that even though I’d never met her great-aunt, I’d nailed her likeness,” Wilkins adds with deserved pride and satisfaction.

One challenge that Wilkins never resolved was his inability to attach or affix the busts to their pedestals. “As a result, they get knocked off and broken from time to time,” Wilkins discloses. Like the time a Boston Red Sox player broke into the Harborside and knocked all of the busts off their pedestals except for the one of Paul Dunbar. “He created $4,500 in damage, but the incident was handled without any publicity so few people ever knew.”

One challenge that Wilkins never resolved was his inability to attach or affix the busts to their pedestals. “As a result, they get knocked off and broken from time to time,” Wilkins discloses. Like the time a Boston Red Sox player broke into the Harborside and knocked all of the busts off their pedestals except for the one of Paul Dunbar. “He created $4,500 in damage, but the incident was handled without any publicity so few people ever knew.”

The original cost of the busts was $7,000 apiece.

Chief Billy Bowlegs

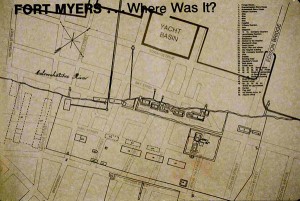

The Second Seminole War ended in 1842, and for the next 8 years, Chief Billy Bowlegs and his people lived in peace on the edge of the Everglades, several miles south of Fort Myers. But in 1850, the federal government established a new fort in Indian territory in abrogation of the treaty they entered into with the chief in 1842. The murder of a trader by the name of Whiddon in Charlotte Harbor was the reason given for building the new fort, but in actuality, the wealthy plantation owners in the northern part of Florida had never given up their dreams of draining and converting the Everglades into lucrative sugar cane and rice plantations worked by slaves. For for this to happen, the remaining Indians had to go and the trader’s murder was just the excuse they needed.

The Second Seminole War ended in 1842, and for the next 8 years, Chief Billy Bowlegs and his people lived in peace on the edge of the Everglades, several miles south of Fort Myers. But in 1850, the federal government established a new fort in Indian territory in abrogation of the treaty they entered into with the chief in 1842. The murder of a trader by the name of Whiddon in Charlotte Harbor was the reason given for building the new fort, but in actuality, the wealthy plantation owners in the northern part of Florida had never given up their dreams of draining and converting the Everglades into lucrative sugar cane and rice plantations worked by slaves. For for this to happen, the remaining Indians had to go and the trader’s murder was just the excuse they needed.

At first, the government tried to persuade Billy Bowlegs and his people to leave voluntarily. When those efforts failed, the government decided to squeeze them out by closing all trading posts to the Indians and opening roads through the territory given to the Indians at the close of the Second Seminole War. When even that failed to produce the desired result, the soldiers at the fort took matters into their own hands.

In December of 1855, Lt. George Hartsuff and a survey party were dispatched from the fort to find out where the Seminoles were living. Historians believe that Hartsuff provoked an incident in order to create support among the settlers for rounding up the Seminoles, but he underestimated the swiftness of Bowlegs’ reprisals. The following morning, Bowlegs and his warriors attacked Hartsuff’s camp, killing two surveyors and wounding Hartsuff and three of his men. They barely made it back to the fort alive. (Legend has it that Hartsuff hacked up Bowlegs’ banana plantation and then tossed the Chief to the ground when Bowlegs protested about it, prompting the Chief and his warriors to go on the warpath.)

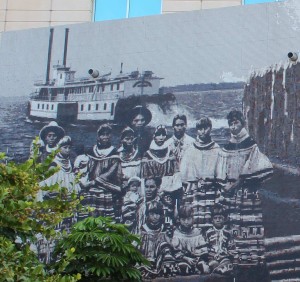

For more than two years, Bowlegs and his warriors engaged in a campaign of guerrilla warfare. They ambushed the soldiers by day and attacked them under cover of darkness at night before slipping back into the impenetrable swamps of the Big Cypress. But by 1858, war-weary and starving, the Seminole chief had enough. He entered into peace negotiations. “A shrewd bargainer,” reports muralist Barbara Jo Revelle, “Billy Bowlegs received $7,500 for himself and generous amounts for his tribe.” (Some historians place the amount at $10,000 for Bowlegs and $1,000 for each of his chiefs. ) He also received assurances that he and his tribe would be settled on land apart from the Creeks living in the resettlement area.

For more than two years, Bowlegs and his warriors engaged in a campaign of guerrilla warfare. They ambushed the soldiers by day and attacked them under cover of darkness at night before slipping back into the impenetrable swamps of the Big Cypress. But by 1858, war-weary and starving, the Seminole chief had enough. He entered into peace negotiations. “A shrewd bargainer,” reports muralist Barbara Jo Revelle, “Billy Bowlegs received $7,500 for himself and generous amounts for his tribe.” (Some historians place the amount at $10,000 for Bowlegs and $1,000 for each of his chiefs. ) He also received assurances that he and his tribe would be settled on land apart from the Creeks living in the resettlement area.

The deal struck, Bowlegs returned two weeks later with 124 warriors,women, children and elders from his tribe. On May 4, 1858, they boarded the steamer Grey Cloud bound for New Orleans and ultimately the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Regrettably, Bowlegs did not have the opportunity to enjoy much of the relocation money he and his tribe received. He died on April 27, 1859, shortly after reaching the lands set aside for him and his tribe in Oklahoma.

The deal struck, Bowlegs returned two weeks later with 124 warriors,women, children and elders from his tribe. On May 4, 1858, they boarded the steamer Grey Cloud bound for New Orleans and ultimately the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Regrettably, Bowlegs did not have the opportunity to enjoy much of the relocation money he and his tribe received. He died on April 27, 1859, shortly after reaching the lands set aside for him and his tribe in Oklahoma.

Chief Billy Bowlegs is one of the people featured by photographer Barbara Jo Revelle in her 20′ tall by 100 foot long ceramic tile mural, Fort Myers: An Alternative History.

Captain Francis Asbury Hendry

According to the plaque beneath his bust, “F.A. Hendry was born in Georgia in 1833 and moved to Florida with his parents in 1851.

According to the plaque beneath his bust, “F.A. Hendry was born in Georgia in 1833 and moved to Florida with his parents in 1851.

- Francis Asbury Hendry first visited the fort from which the city takes its name in 1853, when “there was not a single settler or trace of civilization in the surrounding country.”

- “The fort presented a beautiful appearance,” wrote the 20-year-old Hendry following his visit.

“The grounds were tastefully laid out with shell walls and dress parade grounds and beautifully adorned with many kinds of palms. The velvety lawn was carefully attended. Special care was given to the rock rimmed riverbanks. I beheld the finest vegetable garden I ever saw. It was the property of the garrison and the vegetables were supplied to the different companies in any quantities needed. Near the garden there was a grove of small orange trees. The long lines of uniformed soldiers with white gloves and burnished guns, and the officers with their golden epaulettes and shining side arms were grand and magnificent to behold. Captain McKay’s store and the large commissary were well filled and tastily stored, amply supplying the soldiers’ needs. The wagon yard and stables were exceptionally well kept and the horses and mules were as fat and sleek as corn, oats and hay could make them, and all were groomed to perfection. My pen would fail to describe the hospital with its light and airy rooms and so spotlessly clean. The officers and men were very courteous and kind, and a more comfortable and happy set of men I never saw.”

“The grounds were tastefully laid out with shell walls and dress parade grounds and beautifully adorned with many kinds of palms. The velvety lawn was carefully attended. Special care was given to the rock rimmed riverbanks. I beheld the finest vegetable garden I ever saw. It was the property of the garrison and the vegetables were supplied to the different companies in any quantities needed. Near the garden there was a grove of small orange trees. The long lines of uniformed soldiers with white gloves and burnished guns, and the officers with their golden epaulettes and shining side arms were grand and magnificent to behold. Captain McKay’s store and the large commissary were well filled and tastily stored, amply supplying the soldiers’ needs. The wagon yard and stables were exceptionally well kept and the horses and mules were as fat and sleek as corn, oats and hay could make them, and all were groomed to perfection. My pen would fail to describe the hospital with its light and airy rooms and so spotlessly clean. The officers and men were very courteous and kind, and a more comfortable and happy set of men I never saw.”  The 6’1″ gray-eyed 21-year-old returned to the fort a year later as a guide to Lt. Henry Benson to ascertain if it was practical to open an overland through-route to Fort Myers.

The 6’1″ gray-eyed 21-year-old returned to the fort a year later as a guide to Lt. Henry Benson to ascertain if it was practical to open an overland through-route to Fort Myers.- Hendry next visited the fort under less hospitable circumstances when, as captain of a 131-man company that he raised and commanded himself, he joined with Major William Footman’s Cow Calvary or “Cattle Battalion” in an unsuccessful attack on Fort Myers on February 20, 1865 in what turned out to be the southernmost battle of the Civil War. The operation’s objective was not per se control of the fort. Rather, they were after a herd of 4,500 cattle that the Union soldiers had confiscated from cattle ranches between Fort Myers and Tampa. The beef was desperately needed by the Confederacy, but the Cow Calvary was repelled by elements of Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. [A lengthier and more complete description of the Battle of Fort Myers can be found in the profile on D.J. Wilkins’ Clayton, a statue dedicated to the gallant soldiers of the USTC who fought in that engagement “as well as all of the 180,000 African American soldiers who bravely fought in the Civil War.”]

- After the Civil War, the fort was abandoned and the Hendry Clan, whose herds, numbering 12,000 head, grazed on grasslands in the Fort Thompson area about 30 miles east of the vacated fort, moved their families to the tiny hamlet of Fort Myers rather than stay in the lonely reaches of the prairie where the cattle grazed. FA chose as his home one of the abandoned officer’s quarters, which he refurbished.

- Relatives joined them, and by 1873, about ten families were living in the little settlement.

- Over the next 15 years, Hendry established a cattle export business to Cuba, constructed wharves and pens in Punta Rassa to support the operation, and built his herd to 50,000 head, gaining the title of “Cattle King of South Florida.”

The plaque further relates that Hendry “became very active in politics as State Senator from 1875-1877, State Representative from 1893-1904, he was on the first town council of Fort Myers in 1885 and also the first county commission of Lee County in 1887.”

- Hendry was one of the 10 founding fathers and chaired the meeting that resulted in the city’s incorporation on August 12, 1885.

- By 1887, the town had grown to around 1,000 people and when the region decided to secede from Monroe County and form a county of their own, it was Francis Asbury Hendry who suggested that the new county be named after General Lee.

- Ironically, Hendry moved back to Fort Thompson in 1888 to focus on cattle breeding and his citrus groves.

- In 1895, Hendry platted LaBelle, which he named for his daughters, Laura and Belle.

- When the 764,911-acre area decided on May 11, 1923 to split from Lee County and form their own government, it was named (posthumously) after Hendry (with the new local government to the south being named after Barron Collier).

- LaBelle is the county seat of Hendry County.

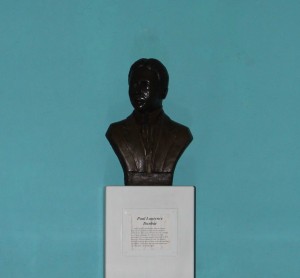

Paul Laurence Dunbar

The plaque beneath his bust states that “Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1872 and lived there until his death in 1906. In this short period, he proved to be a prolific poet, being among the first black poets to be published. The new segregated school built in Fort Myers in 1926 was named for him. The Dunbar School eventually gave its name to the surrounding community which until that time had been known as ‘Pinetucky’ or ‘Safety Hill.'”

The plaque beneath his bust states that “Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1872 and lived there until his death in 1906. In this short period, he proved to be a prolific poet, being among the first black poets to be published. The new segregated school built in Fort Myers in 1926 was named for him. The Dunbar School eventually gave its name to the surrounding community which until that time had been known as ‘Pinetucky’ or ‘Safety Hill.'”

Dunbar’s father was a Civil War veteran who served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment.

Dunbar’s father was a Civil War veteran who served in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and the 5th Massachusetts Colored Cavalry Regiment.- Dunbar wrote his first poem at age 6 and gave his first public recital at age 9.

- His mother Matilda assisted him in his schooling, having learned how to read expressly for that purpose.

- Dunbar wrote a dozen books of poetry, four books of short stories, five novels and a play.

- In 1903, he also wrote lyrics for In Dahomey – the first musical to appear on Broadway written and performed entirely by African-Americans. One of the more successful theatrical productions of its time, the musical comedy successfully toured England and America over a period of four years.

- His essays and poems were published widely in the leading journals of the day, including Harper’s Weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, the Denver Post, Current Literature and a number of other publications.

- Dunbar died from tuberculosis on February 9, 1906 at the age of thirty-three.

Tootie McGregor Terry

Tootie McGregor ne’ Jerusha H. Barber was a woman’s whose real life is the stuff of a Charlotte Bronte or Nathaniel Hawthorne romance novel. Born in 1843 to a middle class Cleveland judge by the name of Epaphras Barber, she fell in love during high school with Marshall Terry, a struggling medical student who was so poor he didn’t dare ask for her hand in marriage. Jerusha’s love went unrequited as Terry set off to seek his fortune, serving in the Spanish-American War and eventually becoming the surgeon general of the state of New York.

Tootie McGregor ne’ Jerusha H. Barber was a woman’s whose real life is the stuff of a Charlotte Bronte or Nathaniel Hawthorne romance novel. Born in 1843 to a middle class Cleveland judge by the name of Epaphras Barber, she fell in love during high school with Marshall Terry, a struggling medical student who was so poor he didn’t dare ask for her hand in marriage. Jerusha’s love went unrequited as Terry set off to seek his fortune, serving in the Spanish-American War and eventually becoming the surgeon general of the state of New York.

Jerusha didn’t wait. She met, was wooed by and married a young salesman by the name of Ambrose McGregor. Ambrose combined ambition with hard work as he set about making a name for himself. His young bride helped, pinching pennies and sewing Ambrose’s clothes in the newlyweds’ rented apartment above a local grocery store. Ambrose succeeded in spectacular fashion, eventually becoming the president of an oil company by the name of Standard Oil.

Jerusha didn’t wait. She met, was wooed by and married a young salesman by the name of Ambrose McGregor. Ambrose combined ambition with hard work as he set about making a name for himself. His young bride helped, pinching pennies and sewing Ambrose’s clothes in the newlyweds’ rented apartment above a local grocery store. Ambrose succeeded in spectacular fashion, eventually becoming the president of an oil company by the name of Standard Oil.

“Tootie” and Ambrose had but one child, a son they named Bradford. The boy was sickly, and his doctors advised the couple to winter in Florida where the temperate climate would have a beneficial effect on Bradford’s health. Lured by its fine tarpon fishing, Ambrose and Tootie fell in love with Fort Myers and purchased, in 1892, the house next door to the Edison Estate. Over the next eight years, Ambrose bought more than 30 local properties, invested in citrus and bankrolled a young real estate developer by the name of Harvie Heitman. Regrettably, the oil tycoon died of cancer in 1900 at the age of 57. However, he left Tootie a very wealthy widow, with an estate exceeding $6 million.

“Tootie” and Ambrose had but one child, a son they named Bradford. The boy was sickly, and his doctors advised the couple to winter in Florida where the temperate climate would have a beneficial effect on Bradford’s health. Lured by its fine tarpon fishing, Ambrose and Tootie fell in love with Fort Myers and purchased, in 1892, the house next door to the Edison Estate. Over the next eight years, Ambrose bought more than 30 local properties, invested in citrus and bankrolled a young real estate developer by the name of Harvie Heitman. Regrettably, the oil tycoon died of cancer in 1900 at the age of 57. However, he left Tootie a very wealthy widow, with an estate exceeding $6 million.

Bradford died soon after. (He married his high school sweetheart, Florence Quintard, in September of 1902, just two days before his death.)

With both her husband and son now deceased, Tootie could have packed up and moved back to Cleveland, but she remained faithful to Fort Myers. In fact, she decided to take an active role in the city’s development, starting with the improvement of Lee County’s roadways. She became frustrated with cattle and other animals damaging the streets, especially Riverside Avenue, which was still being used to drive cattle from La Belle and Fort Thompson to the cow pens in Punta Rassa, where they were loaded on freighters bound for Havana and other ports of call. So Tootie made an offer to the city and Lee County that they couldn’t refuse. If they agreed to pave Riverside Avenue from Whiskey Creek to downtown Fort Myers, she would cover the costs of having the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa paved. She agreed to use whatever materials the City and County chose, and put in all necessary bridges and culverts along the way. She even offered to pay $500 annually to maintain the new road for five years after construction was finished. Unfortunately, Tootie did not live long enough to see the completion of the roadway, which was named McGregor Boulevard in honor of Ambrose McGregor, as Tootie had requested.

With both her husband and son now deceased, Tootie could have packed up and moved back to Cleveland, but she remained faithful to Fort Myers. In fact, she decided to take an active role in the city’s development, starting with the improvement of Lee County’s roadways. She became frustrated with cattle and other animals damaging the streets, especially Riverside Avenue, which was still being used to drive cattle from La Belle and Fort Thompson to the cow pens in Punta Rassa, where they were loaded on freighters bound for Havana and other ports of call. So Tootie made an offer to the city and Lee County that they couldn’t refuse. If they agreed to pave Riverside Avenue from Whiskey Creek to downtown Fort Myers, she would cover the costs of having the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa paved. She agreed to use whatever materials the City and County chose, and put in all necessary bridges and culverts along the way. She even offered to pay $500 annually to maintain the new road for five years after construction was finished. Unfortunately, Tootie did not live long enough to see the completion of the roadway, which was named McGregor Boulevard in honor of Ambrose McGregor, as Tootie had requested.

Tootie owned the Royal Palm and Riverside Hotels, and collaborated with Ambrose’s partner, Harvie Heitman on the construction of a hotel at the corner of First and Hendry streets to be named “The Bradford” in honor of her son. But she did not forget her native Cleveland. In Pioneer Families of Cleveland, author Gertrude Wickham writes that Tootie “was a very bright, attractive woman and was much use to the world.” She partnered with her sister, Sophia Barber McCrosky, to found one of that city’s first private nursing homes. The sisters conceived it as a place for “gentlewomen who could no longer care for themselves.” Also named for Ambrose, the the A.M. McGregor Home was incorporated in 1904, opened in 1908 with 25 residents, and still serves Ohio’s elderly today.

Tootie owned the Royal Palm and Riverside Hotels, and collaborated with Ambrose’s partner, Harvie Heitman on the construction of a hotel at the corner of First and Hendry streets to be named “The Bradford” in honor of her son. But she did not forget her native Cleveland. In Pioneer Families of Cleveland, author Gertrude Wickham writes that Tootie “was a very bright, attractive woman and was much use to the world.” She partnered with her sister, Sophia Barber McCrosky, to found one of that city’s first private nursing homes. The sisters conceived it as a place for “gentlewomen who could no longer care for themselves.” Also named for Ambrose, the the A.M. McGregor Home was incorporated in 1904, opened in 1908 with 25 residents, and still serves Ohio’s elderly today.

After Bradford’s untimely demise, Marshall Terry re-entered the picture. He had never married and was still carrying a torch for Tootie. He fanned the smoldering embers of their decades-idle romance into a torrid fire, and induced Tootie to marry him in 1905. The following year, the couple donated 40 acres of land to the city for use as the spring training facility for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians and Fort Myers Palms. Today, this tract bears the name of Terry Park.

After Bradford’s untimely demise, Marshall Terry re-entered the picture. He had never married and was still carrying a torch for Tootie. He fanned the smoldering embers of their decades-idle romance into a torrid fire, and induced Tootie to marry him in 1905. The following year, the couple donated 40 acres of land to the city for use as the spring training facility for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians and Fort Myers Palms. Today, this tract bears the name of Terry Park.

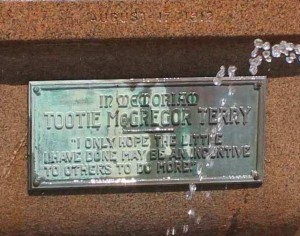

Tootie and Marshall enjoyed six years together. She died on August 17, 1912 at her summer home at Mamaroneck-on-the-Hudson in New York. Following Tootie’s death, Dr. Marshall assumed responsibility for completing the road work that his wife had undertaken and decided to donate a fountain to the city in honor of his late wife, inscribing it with her own words, “I only hope the little I have done may be an incentive to others to do more.” Known as the Tootie McGregor Fountain, the memorial sits today outside the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club.

Tootie and Marshall enjoyed six years together. She died on August 17, 1912 at her summer home at Mamaroneck-on-the-Hudson in New York. Following Tootie’s death, Dr. Marshall assumed responsibility for completing the road work that his wife had undertaken and decided to donate a fountain to the city in honor of his late wife, inscribing it with her own words, “I only hope the little I have done may be an incentive to others to do more.” Known as the Tootie McGregor Fountain, the memorial sits today outside the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club.

Thomas Alva Edison

It is beyond the scope of this profile to present a complete biography for Thomas Edison or to even chronicle his connection to the City of Fort Myers. Suffice it here to repeat the verbiage contained in the plaque that appears beneath his bust in the Harborside Event Center:

It is beyond the scope of this profile to present a complete biography for Thomas Edison or to even chronicle his connection to the City of Fort Myers. Suffice it here to repeat the verbiage contained in the plaque that appears beneath his bust in the Harborside Event Center:

“Thomas Alva Edison was born in Ohio on February 11, 1847 and died in New Jersey on October 18, 1931. Edison first came to Fort Myers in March 1885 and was impressed with the lush growth and beautiful surroundings and immediately purchased property along the Caloosahatchee River. He spent many winters in Fort Myers from 1901 to 1931, and worked on the production of plant-based rubber in his laboratory here. He did some electrical research here, trying to perfect the light bulb and electricity generators. He is also remembered for the planting of royal palms along McGregor Boulevard. The Edison Winter Home was donated to the City of Fort Myers by the late inventor’s window in 1947.”

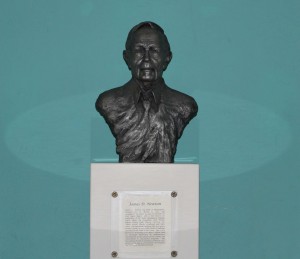

James D. Newton

The plaque for this developer, author and philanthropist states:

“James D. Newton was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 30, 1905 and “graduated” December 13, 1999 from his home on Fort Myers Beach. Jim is best known for authorship of his book, Uncommon Friends, which describes his friendship with Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Dr. Alexis Carrel, Charles Lindbergh and their wives. Jim married his beloved wife of 56 years, Eleanor Forde, in 1943 with Charles Lindbergh standing beside him as best man. Jim is also known for developing Fort Myers’ Edison Park on McGregor Boulevard, his philanthropic contributions to the citizens of Lee County and his commitment to educational programs. The Uncommon Friends Foundation, formed in 1993, preserves the legacy of the friendships the Newtons had with their uncommon friends.”

“James D. Newton was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 30, 1905 and “graduated” December 13, 1999 from his home on Fort Myers Beach. Jim is best known for authorship of his book, Uncommon Friends, which describes his friendship with Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Dr. Alexis Carrel, Charles Lindbergh and their wives. Jim married his beloved wife of 56 years, Eleanor Forde, in 1943 with Charles Lindbergh standing beside him as best man. Jim is also known for developing Fort Myers’ Edison Park on McGregor Boulevard, his philanthropic contributions to the citizens of Lee County and his commitment to educational programs. The Uncommon Friends Foundation, formed in 1993, preserves the legacy of the friendships the Newtons had with their uncommon friends.”

Newton became acquainted with his uncommon friends by virtue of averting a public relations disaster over the entrance he planned for his Edison Park development. Sculptor Helmuth van Zengen was carving a Grecian maiden for the columned entry when the town’s ladies discovered that she was naked. When Mina Edison complained on behalf of the community, Newton quickly had van Zengen craft a veil made of powdered marble to discretely cover his nude, thereby winning Mrs. Edison’s favor and Thomas Edison’s enduring friendship. That sculpture is known as The Spirit of Fort Myers and it is the second oldest work in the City’s public art collection.

Newton became acquainted with his uncommon friends by virtue of averting a public relations disaster over the entrance he planned for his Edison Park development. Sculptor Helmuth van Zengen was carving a Grecian maiden for the columned entry when the town’s ladies discovered that she was naked. When Mina Edison complained on behalf of the community, Newton quickly had van Zengen craft a veil made of powdered marble to discretely cover his nude, thereby winning Mrs. Edison’s favor and Thomas Edison’s enduring friendship. That sculpture is known as The Spirit of Fort Myers and it is the second oldest work in the City’s public art collection.

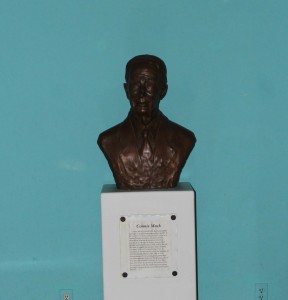

Connie Mack

According to the plaque for Connie Mack:

“Connie Mack (Cornelius McGillicuddy) was born to Scottish immigrant parents in 1863. At the age of 21, he launched his baseball career as a catcher. During his stint as a catcher for the Washington Senators, he was involved in two historic firsts. He was on the first team to have spring training in Florida in 1888, and he was the first man to suggest that pitchers begin throwing overhand. After an 11 year playing career, he continued in baseball as the owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics from 1901 to 1950, having managed, won and lost more games than any other manager in history. The Kiwanis Club of Fort Myers lured Mack’s Athletics to Fort Myers from 1923-1936. By the time of his death in 1956, he was known as Mr. Baseball and caused spring training to become firmly entrenched in Fort Myers history.”

“Connie Mack (Cornelius McGillicuddy) was born to Scottish immigrant parents in 1863. At the age of 21, he launched his baseball career as a catcher. During his stint as a catcher for the Washington Senators, he was involved in two historic firsts. He was on the first team to have spring training in Florida in 1888, and he was the first man to suggest that pitchers begin throwing overhand. After an 11 year playing career, he continued in baseball as the owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics from 1901 to 1950, having managed, won and lost more games than any other manager in history. The Kiwanis Club of Fort Myers lured Mack’s Athletics to Fort Myers from 1923-1936. By the time of his death in 1956, he was known as Mr. Baseball and caused spring training to become firmly entrenched in Fort Myers history.”

Location and Dimensions

- The Harborside Event Center is located at 1375 Monroe Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901.

- Its map coordinates are N 26° 38′ 38.967″ latitude and W 81° 52′ 20.0165″ longitude.

D.J. Wilkins’ Other Public Artworks

Besides the Harborside Collection, Wilkins’ resume includes Uncommon Friends, a sculpture depicting Fort Myers’ iconic winter residents Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone gathered around a campfire on a tiny island in the middle of a reflection pool and fountain. Long regarded as the sculptural symbol of Fort Myers, the installation resides at the Monroe Street entrance to Centennial Park and within eye shot of three more of Wilkins’ outdoor sculptures, The Great Turtle Chase, Clayton and The Florida Panther on Monroe Street. Wilkins also cast statues of Thomas Edison at the Edison Estate and the Lee campus of Edison State College, a bust of Henry Ford for the Henry Ford Home, and a memorial to legendary Fort Myers High School swimming coach Wes Nott.

Besides the Harborside Collection, Wilkins’ resume includes Uncommon Friends, a sculpture depicting Fort Myers’ iconic winter residents Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone gathered around a campfire on a tiny island in the middle of a reflection pool and fountain. Long regarded as the sculptural symbol of Fort Myers, the installation resides at the Monroe Street entrance to Centennial Park and within eye shot of three more of Wilkins’ outdoor sculptures, The Great Turtle Chase, Clayton and The Florida Panther on Monroe Street. Wilkins also cast statues of Thomas Edison at the Edison Estate and the Lee campus of Edison State College, a bust of Henry Ford for the Henry Ford Home, and a memorial to legendary Fort Myers High School swimming coach Wes Nott.

Wilkins has also played an instrumental role in restoring several of Southwest Florida’s public sculptures including The Spirit of Fort Myers at the entrance to Edison Park, the Tootie McGregor Fountain in front of the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club and the Iwo Jima Memorial in Eco Park on Veteran’s Parkway in Cape Coral.

Wilkins has also played an instrumental role in restoring several of Southwest Florida’s public sculptures including The Spirit of Fort Myers at the entrance to Edison Park, the Tootie McGregor Fountain in front of the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club and the Iwo Jima Memorial in Eco Park on Veteran’s Parkway in Cape Coral.

About the Harborside Event Center

Harborside Event Center is a fully-wired 42,000 sq. ft. convention, conference and special event facility that is located across from Centennial Park in the northwest corner of the downtown Fort Myers River District. Its versatile seating configurations allows it to comfortably accommodate multiple and simultaneous events that include tradeshows and large exhibitions, concerts and sporting events, meetings, black-tie galas, weddings and even more intimate gatherings.

Harborside Event Center is a fully-wired 42,000 sq. ft. convention, conference and special event facility that is located across from Centennial Park in the northwest corner of the downtown Fort Myers River District. Its versatile seating configurations allows it to comfortably accommodate multiple and simultaneous events that include tradeshows and large exhibitions, concerts and sporting events, meetings, black-tie galas, weddings and even more intimate gatherings.

The Harborside is not done growing. Under the City’s 2010 Riverfront Redevelopment Plan, the Event Center will receive an 82,000 square-foot addition that will triple its size. At the same time, a 12-story, 220-room convention-quality hotel overlooking the river will be added to the downtown skyline, as will a bevy of outstanding riverfront restaurants and shops, a parking garage to accommodate these new facilities, and plenty of public plazas, open areas and expanded marina facilities. In sum, these improvements will convert Fort Myers into a tourism and convention destination at the heart of which lies the Harborside Event Center.

The Harborside is not done growing. Under the City’s 2010 Riverfront Redevelopment Plan, the Event Center will receive an 82,000 square-foot addition that will triple its size. At the same time, a 12-story, 220-room convention-quality hotel overlooking the river will be added to the downtown skyline, as will a bevy of outstanding riverfront restaurants and shops, a parking garage to accommodate these new facilities, and plenty of public plazas, open areas and expanded marina facilities. In sum, these improvements will convert Fort Myers into a tourism and convention destination at the heart of which lies the Harborside Event Center.

Fast Facts.

- Greg Biolchini is a representational realist who originally hails from the Windy City, where weekend trips to the Chicago Art Institute lit the creative fire in him at an early age. As a youth, his family relocated to the wilds of Southwest Florida, where he continued to hone his painting skills, drawing inspiration from the natural world around him. Later, apprenticeship under portrait painter David Phillip Wilson coupled with courses at the Ringling School of Art led to a rewarding fine art career. For over 40 years, his paintings have continued to bring life to portraits, wildlife, and landscapes. Among his honors, Greg was voted Southwest Florida’s Visual Artist of the year and achieved Master Status in the Pastel Society of America.

The FAU computer system for creating 3D models of faces from 2D images starts with a generic 3D “synthetic face,” the basic parameters of which are obtained from a number of 3D images of actual human faces.

The FAU computer system for creating 3D models of faces from 2D images starts with a generic 3D “synthetic face,” the basic parameters of which are obtained from a number of 3D images of actual human faces.- When a 2D image of a specific person is presented, the computer projects the synthetic face onto that flat image plane.

- The algorithm, compensating for the pose and illumination of the 2D face, transfers the subject’s features onto the synthetic face, to create a 3D approximation.

- The FAU researchers who’ve developed the algorithm believe that the technology could be applied not only to photographs but also to CCTV security footage for use in criminal investigations or searches for missing persons.

Links.

Reflecting on the life of the ‘Father of Fort Myers,’ Capt. F.A. Hendry (02-17-14)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.