Clayton

“People don’t have a sense of connection, a sense of history here because so many folks are from elsewhere,” muses D.J. Wilkins (right), the man former mayor Art Hammel once termed the Sculptor of Fort Myers. “But American history started right here, with footprints of the Conquistadors in the sands of Florida. And Fort Myers has the distinction of being the site of the southernmost battle of the Civil War,* an engagement won due to the bravery of the men who fought in the 2nd Regiment of the USCT.”

“People don’t have a sense of connection, a sense of history here because so many folks are from elsewhere,” muses D.J. Wilkins (right), the man former mayor Art Hammel once termed the Sculptor of Fort Myers. “But American history started right here, with footprints of the Conquistadors in the sands of Florida. And Fort Myers has the distinction of being the site of the southernmost battle of the Civil War,* an engagement won due to the bravery of the men who fought in the 2nd Regiment of the USCT.”

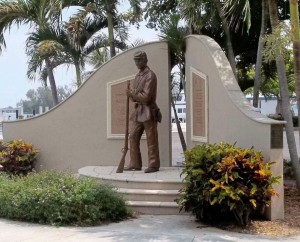

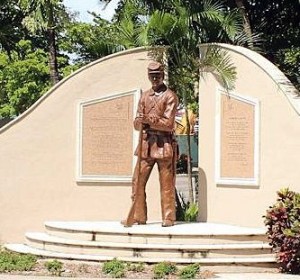

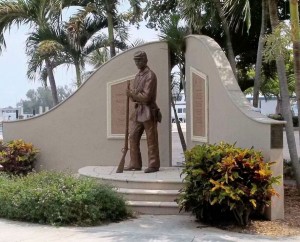

The acronym stands for the United States Colored Troops, and in 2000, the City of Fort Myers commissioned Wilkins to create a tribute to their gallantry. You’ll find the memorial on the eastern edge of Centennial Park, a 10-acre mall on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River that is itself a memorial to the City’s 100th anniversary.

The acronym stands for the United States Colored Troops, and in 2000, the City of Fort Myers commissioned Wilkins to create a tribute to their gallantry. You’ll find the memorial on the eastern edge of Centennial Park, a 10-acre mall on the banks of the Caloosahatchee River that is itself a memorial to the City’s 100th anniversary.

What it is

The memorial features a larger-than-life “bronze” of a sergeant in the United States Colored Troops 2nd Regiment. He is standing before a gate within a wall. The gate symbolizes freedom from slavery. The soldier memorializes all African Americans who served during the Civil War.

The memorial features a larger-than-life “bronze” of a sergeant in the United States Colored Troops 2nd Regiment. He is standing before a gate within a wall. The gate symbolizes freedom from slavery. The soldier memorializes all African Americans who served during the Civil War.

The soldier is framed by two granite plaques. The one on the left is the dedication. It contains a four sentence summary of the battle fought on February 20, 1865 in which Union forces anchored by members of the USCT repelled an attack by Confederates sent to destroy the fort and  capture some 4,000 head of cattle needed by the Confederacy to feed its last contingents of fighting forces. The inscription also notes that during their tour in southwest Florida, USCT troops freed and enlisted more than 1,000 slaves who had been toiling in the fields and ranches in this part of the South.

capture some 4,000 head of cattle needed by the Confederacy to feed its last contingents of fighting forces. The inscription also notes that during their tour in southwest Florida, USCT troops freed and enlisted more than 1,000 slaves who had been toiling in the fields and ranches in this part of the South.

“They also deprived the Confederacy of salt and molasses,” Wilkins notes for the record.

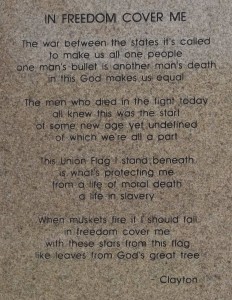

The plaque on the right contains a poem entitled “In Freedom Cover Me” which Wilkins wrote and ascribed to the soldier, “who’s representational and did not really exist.”

Wilkins named the soldier in his memorial Clayton because “it took a ton of clay to sculpt the statue,” which is cast in bronze. Dedicated in 2000, some 135 years after the Battle of Fort Myers, Clayton is a reminder of the rich historical heritage that we enjoy here in Lee County and the City of Fort Myers.

Wilkins named the soldier in his memorial Clayton because “it took a ton of clay to sculpt the statue,” which is cast in bronze. Dedicated in 2000, some 135 years after the Battle of Fort Myers, Clayton is a reminder of the rich historical heritage that we enjoy here in Lee County and the City of Fort Myers.

Dedication

The USCT 2d Regiment Monument was dedicated on Veteran’s Day in 1998 in a ceremony that took place at 10:00 in the morning. The keynote speaker was Four Star General Johnny Edward Wilson (U.S. Army  Material Command of Alexandria, VA), Congressman Alcee Hastings (Florida 23rd District) and State Senator Tom Rossin (D-West Palm Beach, 35th District).

Material Command of Alexandria, VA), Congressman Alcee Hastings (Florida 23rd District) and State Senator Tom Rossin (D-West Palm Beach, 35th District).

An honor guard from the Robert H.L. Dabney American Legion Post 192 dressed as Union soldiers fired muskets to salute Companies D & I of the USCT 2nd Regiment. Post 192 raised $5,000 of the $50,000 it cost to commission the fabrication and installation of the statue and the steps, landing and walls that serve as backdrop for the soldier.

The ceremony also featured a four-jet military flyover.

The dedication was covered  by staff writer Kevin Lollar for the Fort Myers News-Press, who wrote that “throughout the morning, the theme was discovering a lost part of history.”

by staff writer Kevin Lollar for the Fort Myers News-Press, who wrote that “throughout the morning, the theme was discovering a lost part of history.”

Few on November 11, 1998 knew that Fort Myers was a Union outpost or that elements of the USCT 2nd Regiment successfully defended the fort from Confederate attack on February 20, 1865. “This observation means a lot to people in Lee County’s black community, who have had to fight for their place in local history, as well as for their place in contemporary society,” the News-Press added in a separate editorial.

Commemoration of 20th Anniversary of Dedication

On Monday, November 12, 2018, the Fort Myers Chapter of the NAACP in conjunction with the Robert H.L. Dabney American Legion Post 192 commemorated the 20th anniversary of the dedication of Don D.J. Wilkins’ USCT 2nd Regiment Monument in Centennial Park East together with its recent conservation. The ceremony was attended by roughly a dozen and a half people, including Andrea Grady and Stephanie House, who placed a wreath on an easel next to the heroic-sized statue of a composite of one of the 168 black

On Monday, November 12, 2018, the Fort Myers Chapter of the NAACP in conjunction with the Robert H.L. Dabney American Legion Post 192 commemorated the 20th anniversary of the dedication of Don D.J. Wilkins’ USCT 2nd Regiment Monument in Centennial Park East together with its recent conservation. The ceremony was attended by roughly a dozen and a half people, including Andrea Grady and Stephanie House, who placed a wreath on an easel next to the heroic-sized statue of a composite of one of the 168 black  Union soldiers who were garrisoned in Fort Myers during the final eighteen months of the Civil War. Grady is a 26-year Naval veteran and Commander of the Robert H.L. Dabney American Legion Post 192. House is the Chair of the Veteran Affairs Committee of the Lee County NAACP.

Union soldiers who were garrisoned in Fort Myers during the final eighteen months of the Civil War. Grady is a 26-year Naval veteran and Commander of the Robert H.L. Dabney American Legion Post 192. House is the Chair of the Veteran Affairs Committee of the Lee County NAACP.

“This statue helps to educate the community that African-American people have been fighting for their freedom for  decades and as a people will continue to fight for equality, freedom and justice for all,” House said during the commemoration.

decades and as a people will continue to fight for equality, freedom and justice for all,” House said during the commemoration.

D.J. Wilkins’ Other Public Artworks

Clayton was commissioned by the Fort Myers Beautification Advisory Board,  which added 21 public artworks to the City’s collection during a 20-year span that began in 1983 with the restoration of The Spirit of Fort Myers at the entrance of Edison Park.

which added 21 public artworks to the City’s collection during a 20-year span that began in 1983 with the restoration of The Spirit of Fort Myers at the entrance of Edison Park.

Besides Clayton, Wilkins’ resume includes Uncommon Friends, a sculpture depicting Fort Myers’ iconic winter residents Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone gathered around a campfire  on a tiny island in the middle of a reflection pool and fountain. That public art installation is at the Monroe and Edwards Street entrance into Centennial Park and within eye shot of Clayton, The Great Turtle Chase and The Florida Panther on Monroe Street.

on a tiny island in the middle of a reflection pool and fountain. That public art installation is at the Monroe and Edwards Street entrance into Centennial Park and within eye shot of Clayton, The Great Turtle Chase and The Florida Panther on Monroe Street.

Wilkins also cast the busts of Captain Francis Asbury Hendry, Paul L. Dunbar, Connie Mack Sr., Tootie McGregor Terry,  Thomas Edison, James D. Newton and Chief Billy Bowlegs that collectively form “The Harborside Collection,” a bust of Henry Ford and heroic size statues of Thomas Edison, Mina Edison and Henry Ford at the Edison & Ford Winter Estates (known as the Edison Ford Estates Collection), sculptures of Thomas Edison for both the Lee and Collier campuses of Edison State College, and the

Thomas Edison, James D. Newton and Chief Billy Bowlegs that collectively form “The Harborside Collection,” a bust of Henry Ford and heroic size statues of Thomas Edison, Mina Edison and Henry Ford at the Edison & Ford Winter Estates (known as the Edison Ford Estates Collection), sculptures of Thomas Edison for both the Lee and Collier campuses of Edison State College, and the Wes Nott Statue on the campus of Lee Memorial Hospital.

Wes Nott Statue on the campus of Lee Memorial Hospital.

Wilkins has also played an instrumental role in restoring several of Southwest Florida’s public sculptures including The Spirit of Fort Myers at the entrance to Edison Park, the Tootie McGregor Fountain in front of the Edison Restaurant at the Fort Myers Country Club and the Iwo Jima Memorial in Eco Park on Veteran’s Parkway in Cape Coral.

The Battle of Fort Myers, February 20, 1865

D.J. Wilkins is correct when he says that few people are conversant with Fort Myers’ rich historical past. The city was home to a settlement of Calusa Indians and a fort by the name of Harvie was built on that site in November of 1841 as an outpost shortly before the end of the Second Seminole War. It was situated along the banks of the Caloosahatchee River where

D.J. Wilkins is correct when he says that few people are conversant with Fort Myers’ rich historical past. The city was home to a settlement of Calusa Indians and a fort by the name of Harvie was built on that site in November of 1841 as an outpost shortly before the end of the Second Seminole War. It was situated along the banks of the Caloosahatchee River where  today sit the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center and the Arcade Building that’s home to Arts for ACT Gallery and the Florida Repertory Theatre.

today sit the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center and the Arcade Building that’s home to Arts for ACT Gallery and the Florida Repertory Theatre.

The redoubt was abandoned on March 21, 1842, but the old breastworks were rebuilt, expanded and renamed in 1850, and Fort Myers functioned as the center of operations during the Third Seminole War.  After Chief Billy Bowlegs and his tribe agreed to be resettled in Oklahoma, the fort was again abandoned, but was re-garrisoned in January of 1964 by 5 companies from the 110th New York Infantry and the 2nd Florida Union Calvary in order to interrupt the shipment of cattle to Confederate troops from Tennessee who were in Georgia fighting Sherman and other Union

After Chief Billy Bowlegs and his tribe agreed to be resettled in Oklahoma, the fort was again abandoned, but was re-garrisoned in January of 1964 by 5 companies from the 110th New York Infantry and the 2nd Florida Union Calvary in order to interrupt the shipment of cattle to Confederate troops from Tennessee who were in Georgia fighting Sherman and other Union  contingents and to thwart blockade runners who were trading cattle in Cuba for provisions needed by the cattle ranchers.

contingents and to thwart blockade runners who were trading cattle in Cuba for provisions needed by the cattle ranchers.

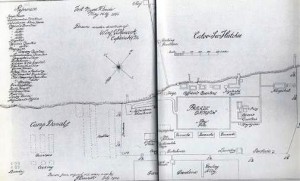

By the time Captain Richard A. Graeffe and his soldiers arrived at the fort, most of the wood stockade had disappeared, so he ordered his men to construct an earthen wall 15 feet wide by 7 feet tall.  Three guard towers were also constructed: one where the hospital had been; a second by the garden and bowling alley; and the third between the stables and riverside warehouse. Then Captain Graeffe sent his troops across the river to begin rounding up the herds of scrub cows being raised by ranchers

Three guard towers were also constructed: one where the hospital had been; a second by the garden and bowling alley; and the third between the stables and riverside warehouse. Then Captain Graeffe sent his troops across the river to begin rounding up the herds of scrub cows being raised by ranchers  between Punta Gorda and Tampa. As they did, resistance began to grow. Captain Graeffe realized he needed reinforcements and Companies D and I of the USCT’s 2nd Regiment were brought up from Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West.

between Punta Gorda and Tampa. As they did, resistance began to grow. Captain Graeffe realized he needed reinforcements and Companies D and I of the USCT’s 2nd Regiment were brought up from Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West.

For the next 10 months, Captain Graeffe sent Companies D and I up the west coast as far north as Tampa in search of more and more cattle. “At that time, southwest Florida was a key cattle  raising area, and the Confederacy needed meat for their troops,” Wilkins points out. “The USCT was determined that they weren’t going to get any.”

raising area, and the Confederacy needed meat for their troops,” Wilkins points out. “The USCT was determined that they weren’t going to get any.”

So zealous was the USCT that by New Year’s Day, 1865, they’d confiscated some 4,500 head. They didn’t keep them at the fort, of course, but drove them down a  sandy trail to Punta Rassa [which subsequently became McGregor Boulevard], where other Union soldiers built a barracks, cow pens and a deep water wharf. There, the cattle were loaded aboard Union vessels and taken to Fort Zachary Taylor, where they were slaughtered and used to feed the sailors who manned the ships that were blockading the Florida coast.

sandy trail to Punta Rassa [which subsequently became McGregor Boulevard], where other Union soldiers built a barracks, cow pens and a deep water wharf. There, the cattle were loaded aboard Union vessels and taken to Fort Zachary Taylor, where they were slaughtered and used to feed the sailors who manned the ships that were blockading the Florida coast.

Some of the local ranchers were pragmatists, and sold their cattle to the Union soldiers rather than suffering their confiscation. But others were Confederates or Confederate sympathizers and the confiscation of their cattle fueled their hatred of Graeffe and his men even before the arrival of the USCT. They absolutely loathed the black soldiers who now roamed southwest Florida stealing their cows and freeing their slaves to boot.

Some of the local ranchers were pragmatists, and sold their cattle to the Union soldiers rather than suffering their confiscation. But others were Confederates or Confederate sympathizers and the confiscation of their cattle fueled their hatred of Graeffe and his men even before the arrival of the USCT. They absolutely loathed the black soldiers who now roamed southwest Florida stealing their cows and freeing their slaves to boot.

The success of the raids alone would have undoubtedly prompted a military response, but the Union soldiers also began to attack Confederate positions along Florida’s west coast. One such foray was especially egregious. According to Sanibel librarian, historian and author Duane Shaffer (Men of Granite: New Hampshire’s Soldiers in the Civil War (University of South  Carolina Press, 2008), soldiers from Fort Myers travelled to Cedar Key by boat in July of 1864 and burned a Confederate outpost at Fort Meade to the ground. The incident became known as the Battle of Station Four.

Carolina Press, 2008), soldiers from Fort Myers travelled to Cedar Key by boat in July of 1864 and burned a Confederate outpost at Fort Meade to the ground. The incident became known as the Battle of Station Four.

A captain by the name of James McKay, Sr. was in charge of the Florida cattle shipments. A highly successful cattleman, he served as Chief Quartermaster for the 7th District of Florida. In that capacity, McKay raised a homegrown force of militia to protect the cattle drives to Georgia. The force consisted of 800 men. Officially, they were named the Florida Special Calvary, 1st Battalion, but everybody referred to them simply as the Cow Calvary. Divided into nine companies, they were placed under the command of Colonel Charles J. Munnerlyn and headquartered in  Fort Meade – the same Fort Meade that the Union soldiers had burned to the ground during the Battle of Station Four.

Fort Meade – the same Fort Meade that the Union soldiers had burned to the ground during the Battle of Station Four.

In January of 1865, Munnerlyn dispatched Major William Footman and three companies of the Cow Calvary to destroy the Union encampment at Fort Myers. Included in that contingent was Capt. F. A. Hendry, who had raised and was commanding a company of 131 men. Footman began the two-week 200-mile march with 275 men, but some sources claim his contingent swelled to as many as 500 men  as angry local farmers, fishermen and other partisans rushed to join the fray. [This claim is disputed by modern scholars with the explanation that Footman would have lacked the resources to feed and provision that many men.]

as angry local farmers, fishermen and other partisans rushed to join the fray. [This claim is disputed by modern scholars with the explanation that Footman would have lacked the resources to feed and provision that many men.]

After resting but a day, they marched down the Caloosahatchee River to mount a surprise attack on the fort the following morning. They camped near Billy’s  Creek, but the undisciplined vanguard of Footman’s force ambushed a handful of black Union soldiers they discovered on picket duty. Alerted by the sound of gunshots, the Union forces inside the fort prepared themselves for battle. Seeing that he’d lost the advantage of surprise, Footman ordered his men to fire a warning shot from their sole piece of artillery, a bronze 12-pounder. Then he sent a messenger under cover of a white flag to demand the fort’s surrender.

Creek, but the undisciplined vanguard of Footman’s force ambushed a handful of black Union soldiers they discovered on picket duty. Alerted by the sound of gunshots, the Union forces inside the fort prepared themselves for battle. Seeing that he’d lost the advantage of surprise, Footman ordered his men to fire a warning shot from their sole piece of artillery, a bronze 12-pounder. Then he sent a messenger under cover of a white flag to demand the fort’s surrender.

One can imagine the expletives a Hollywood script writer would use today to frame new Captain James Doyle’s terse response. But that wasn’t the style more than 150 years ago. A gentleman, Doyle told Footman via his messenger: “Your demand for an unconditional surrender has been received. I respectfully decline; I have force enough to maintain my position and will fight you to the last.”

One can imagine the expletives a Hollywood script writer would use today to frame new Captain James Doyle’s terse response. But that wasn’t the style more than 150 years ago. A gentleman, Doyle told Footman via his messenger: “Your demand for an unconditional surrender has been received. I respectfully decline; I have force enough to maintain my position and will fight you to the last.”

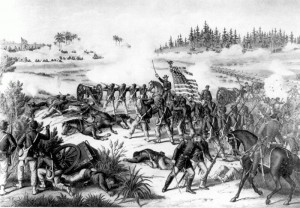

He had his men wheel out the fort’s two Union cannons, and thus began a day long battle in heavy rainfall characterized by heavy cannon and light arms fire. And in the middle of the fiercest fighting were soldiers from the USCT’s 2nd Regiment.

He had his men wheel out the fort’s two Union cannons, and thus began a day long battle in heavy rainfall characterized by heavy cannon and light arms fire. And in the middle of the fiercest fighting were soldiers from the USCT’s 2nd Regiment.

“A N.Y. Times reporter happened to be in Fort Myers at the time,” says sculptor D.J. Wilkins, who researched the event after being commissioned to do the art installation for the City. Irvin D. Soloman was his name, and he reported back to the Times  that “the colored soldiers were in the thickest of the fight. Their impetuosity could hardly be restrained; they seemed totally unconscious of the danger, or regardless of it, and their constant cry was to ‘get at them.’”

that “the colored soldiers were in the thickest of the fight. Their impetuosity could hardly be restrained; they seemed totally unconscious of the danger, or regardless of it, and their constant cry was to ‘get at them.’”

In the heated exchange, former slave John Wallace received a slight head wound which he touted as a badge of honor during Reconstruction when he served as a Republican legislator and gained notoriety with his book Carpetbag Rule in Florida. By nightfall, Major Footman realized that his beleaguered troops  were not going to breech the USCT’s steadfast defense of their position, and he quietly led his dispirited men on the long march back to Fort Meade. Along the way, they jettisoned their cannon and littered their retreat with bandages, splints and the remnants of eaten rations.

were not going to breech the USCT’s steadfast defense of their position, and he quietly led his dispirited men on the long march back to Fort Meade. Along the way, they jettisoned their cannon and littered their retreat with bandages, splints and the remnants of eaten rations.

In all, 40 Confederates were wounded in the battle. The Union lost four men, with three more missing in action. All were members of the United States Colored Troops 2nd Regiment.

“ The Confederacy never got any of the 4,500 cattle that the Union soldiers had confiscated from the surrounding ranches, and the lack of food played a key role in Lee’s decision to surrender at Appomattox six weeks later,” Wilkins contends.

The Confederacy never got any of the 4,500 cattle that the Union soldiers had confiscated from the surrounding ranches, and the lack of food played a key role in Lee’s decision to surrender at Appomattox six weeks later,” Wilkins contends.

“Sadly,” wrote David Stephen Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler and David J. Coles in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War, “racism prevented the proper recognition from being bestowed upon these brave soldiers.” Ironically, it was racism that led the Fort Myers City Council to commission Wilkins to create Clayton. In January of 1997, Population Today magazine published an article naming Fort Myers as one of the  most segregated cities in the entire south. The article was premised on a University of Michigan study based on the results of the 1990 U.S. Census. In January of 1999, the federal government installed a mural in downtown Fort Myers drawing attention to the service of the USTC in the defense of Fort Myers from Confederate attack, prompting the city council to commission its own tribute in the form of Clayton.

most segregated cities in the entire south. The article was premised on a University of Michigan study based on the results of the 1990 U.S. Census. In January of 1999, the federal government installed a mural in downtown Fort Myers drawing attention to the service of the USTC in the defense of Fort Myers from Confederate attack, prompting the city council to commission its own tribute in the form of Clayton.

* D.J. Wilkins’ claim that the Battle of Fort Myers was the “southernmost battle of the Civil War is disputed by a number of Civil War scholars, including City of Fort Myers historian Jim Powers. That’s because the Battle of Palmito Ranch (also known as the Battle of  Palmito Hill) actually took place at a latitude lower than that occupied by Fort Myers. The issue relates to whether the Civil War was actually over by the time the Battle of Palmito Ranch took place on May 12 and 13.

Palmito Hill) actually took place at a latitude lower than that occupied by Fort Myers. The issue relates to whether the Civil War was actually over by the time the Battle of Palmito Ranch took place on May 12 and 13.

- Some historians take the view that the war ended with Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9. If so, then the Battle of Fort Myers would, indeed,

hold the distinction of being the southernmost battle of the Civil War.

hold the distinction of being the southernmost battle of the Civil War. - But the more popular view is that while Lee’s surrender certainly marked the beginning of the end, the war dragged on for several months more.

- After Richmond fell and Davis fled, Confederate commanders were on their own to surrender their

commands to Union forces. Surrenders, paroles, and amnesty for many Confederate combatants would take place over the next several months and into 1866 throughout the South and border states.

commands to Union forces. Surrenders, paroles, and amnesty for many Confederate combatants would take place over the next several months and into 1866 throughout the South and border states. - Not until 16 months after Appomattox did the President formally declare an end to the war.

- On August 20, 1866, President Andrew Johnson issued the following proclamation announcing the end of the American Civil War: “And I do further proclaim that the said insurrection is at an end and that peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now exists in and throughout the whole of the United States of America.”

- Under this construction of historical events, the Battle of Fort Myers can only claim to be the southernmost battle of the Civil War east of the Mississippi River.

The USCT – United States Colored Troops

When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he not only freed enslaved African Americans living in the Confederate states, he certified their ability to serve in the United States military – a position long and vociferously advocated by abolitionist Frederick Douglass. More than five months later, the War Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops which, in turn, designated African American regiments as part of the USCT or United States Colored Troops. The Bureau thereupon established an orderly procedure for recruiting, training, drilling and equipping large number of African Americans.

Members of the USCT distinguished themselves on the battlefield with honor and valor. But they also faced racial bigotry and pervasive opposition to their service, both from within and outside the military. [See “Fast Facts,” below, for additional details on this.]

In allowing African Americans to serve in the armed forces, Lincoln was being neither magnanimous nor enlightened. Military necessity was the driving factor in his decision to include African Americans in the Union Army. He needed both their number and enthusiasm. More than 40,000 paid the ultimate price (30,000 from infection and disease) in their fight for personal freedom and emancipation. By the end of the war, Lincoln came to appreciate just how pivotal a role they had played in the North’s victory over the South, crediting their participation as the tipping point in the war.

By the war’s end, more than 179,000 African American men had served in the Union Army, with another 19,000 serving in the Navy. That represented more than 10 percent of the Union’s overall fighting force. In fact, on the day that Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia, more African Americans were fighting for the Union than the total of all Confederate forces. As a historical note, two of Frederick Douglass’ sons, Charles and Lewis, served in the Union Army.

Location, Measurements and Materials.

- The memorial is located at 26d 38′ 42.7128″ N longitude and 81d 52′ 21.4962″ W latitude.

- The entrance to Centennial Park is located at 2150 Edwards Drive, Fort Myers, FL 33901. Clayton is located across the grass mall to the right (east) of Uncommon Friends.

- Clayton stands 98 inches tall; measures 18 inches wide at the bottom of the soldier’s field jacket; and is 36 inches deep from gun butt to heel of the back foot.

- The walls behind the sculpture span a distance of 28 feet and the landing upon which the sculpture stands measures 13 feet across by 81 inches at its deepest point.

- The figure is made of cold cast bronze, an aggregate consisting of acrylic-modified polyester resin and ground bronze.

- The plaques are granite.

- The wall is stucco over concrete block.

Fast Facts.

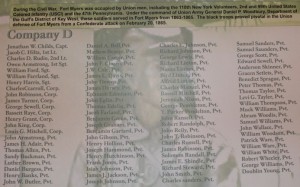

- Some sources place the number of black soldiers stationed at Fort Myers at the time of the battle at 250, but the roster posted at the Williams Academy Black History Museum in Dunbar contains the names of but 168 men, with 91 belonging to Company D and 77 to Company I.

- There were two regiments of the USCT at Fort Zachary Taylor in the Keys, the 2nd and 99th. Both served under the command of Union General Daniel P. Woodbury, Department of the Gulf’s District of Key West.

- Black soldiers faced both opposition, racism and segregation in the Union Army (although African American sailors serving aboard frigates and warships served and slept side by side of their white counterparts).

- Black soldiers and sailors were paid less than whites.

- Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause.

- There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers, but most these were doctors and clergy.

- Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman, who scouted for the 2d South Carolina Volunteers.

- Because of prejudice against them, black units were not used in combat as extensively as they might have been. Nevertheless, the soldiers served with distinction in a number of battles, including Milliken’s Bend, LA, Port Hudson, LA, Petersburg, VA, and Nashville, TN.

- The July 1863 assault on Fort Wagner, SC, in which the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers lost two-thirds of their officers and more than half of their troops, was memorably dramatized in the 1989 motion picture Glory.

- One of the 54th’s soldiers, Sergeant William Carney, became the first African American to win a Medal of Honor after saving the regiment’s colors. When he returned to the decimated battle line, he reportedly exclaimed, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground.”

- By war’s end, 16 black soldiers had been awarded the Medal of Honor for their valor.

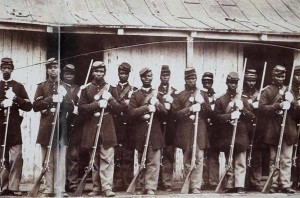

- In 1997, University of Florida photography instructor and artist Barbara Jo Revelle located a rare photograph of some of the men of Companies D and/or I, digitized it, and printed it on the 20 by 100 foot sepia-toned ceramic tile mural that adorns the rear or east wall of the federal courthouse. Titled Fort Myers: An Alternative History, it depicts Billy Bowlegs and a portion of his tribe as the prepare to board the steamer Grey Cloud bound for New Orleans (and ultimately resettlement in the “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma), the stockade at Fort Myers, a steer and cattle rancher representing Fort Myers’ thriving 19th century cattle industry, the locomotive that finally brought rail service to Fort Myers on (ironically) February 20, 1994 and 15 men from the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops.

- Part of the Cow Calvary with whom Companies D & I skirmished on February 20, 1865 included a company of 131 men led by Captain Francis Asbury Hendry. After the war, Hendry returned to cattle ranching and quickly expanded his cattle interests. By 1869, Hendry had built up a herd of 12,000 head which he pastured outside of Fort Thompson east of the old fort. In 1873, he moved his family to Fort Myers, where he chose as his home one of the abandoned officers’ quarters, which he refurbished. Over the next 15 years, his herd grew to 50,000 head and Hendry became known as the “Cattle King of South Florida.” He was one of the 10 founding fathers and chaired the meeting that resulted in the city’s incorporation on August 12, 1885. Two years later, Hendry played an instrumental role in having the county named Lee when the local residents decided to break away from Monroe County and form their own local government.

- Hendry moved to Fort Thompson in 1888 to concentrate on his citrus grove and cattle breeding operations, but he returned to Fort Myers during the final year of his life, probably for easier access to medical care. He died on February 17, 1917.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

For every statue my father has created, he has put his whole heart and sole into each one.

Thank you, Elizabeth Wilkins