“Joe Turner’ cast sublimates personal identities to clearly sing their characters’ songs

Kudos are once again in order for Bill Taylor, Sonya McCarter and the entire theater crew at the Alliance for the Arts, this time for tackling the third of August Wilson’s ambitious Century Cycle series with the psychological drama Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. The language and themes alone are difficult enough, but in this production McCarter fathoms the depths of Wilson’s complex characterizations with a newbie-heavy cast that, to a man and woman, sublimates their identities so that they can clearly sing their characters’ songs.

Kudos are once again in order for Bill Taylor, Sonya McCarter and the entire theater crew at the Alliance for the Arts, this time for tackling the third of August Wilson’s ambitious Century Cycle series with the psychological drama Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. The language and themes alone are difficult enough, but in this production McCarter fathoms the depths of Wilson’s complex characterizations with a newbie-heavy cast that, to a man and woman, sublimates their identities so that they can clearly sing their characters’ songs.

And boiled down to the play’s pure essence, that is the crux of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. As Cicero McCarter’s character, Bynum, tells anyone who will listen, each man (or woman) must find his own song if he (or she) is to be free.

And boiled down to the play’s pure essence, that is the crux of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. As Cicero McCarter’s character, Bynum, tells anyone who will listen, each man (or woman) must find his own song if he (or she) is to be free.

But discovering the key, tempo and rhythm that defines and governs one’s life was easier said than done for African-Americans struggling a half century following Abraham Lincoln’s promulgation of the Emancipation Proclamation on  January 1, 1863 to assimilate themselves into the fabric of white society in the northern cities to which they’d fled.

January 1, 1863 to assimilate themselves into the fabric of white society in the northern cities to which they’d fled.

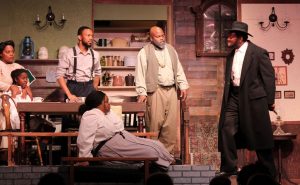

Joe Turner’s Come and Gone takes place in 1911 in the kitchen and living room of a Pittsburgh boardinghouse owned and operated by Seth and Bertha, played by Nuniez Philor (making his theatrical debut) and Tijuanna Clemons (in only her second stage production).  Of all of the characters in Joe Turner, Seth is the most assimilated (read, white). He’s so bent on assuring his financial security and place in America through entrepreneurship that he has little patience for anyone who’s not similarly motivated … or who threatens to derail his personal pursuit of the American dream of home and business ownership, like the frivolous Jeremy or his scary new resident,

Of all of the characters in Joe Turner, Seth is the most assimilated (read, white). He’s so bent on assuring his financial security and place in America through entrepreneurship that he has little patience for anyone who’s not similarly motivated … or who threatens to derail his personal pursuit of the American dream of home and business ownership, like the frivolous Jeremy or his scary new resident,  Loomis.

Loomis.

Bertha is her husband’s counterbalance. In fact, she exercises a calming influence on everyone who sits and takes sustenance at her long wooden kitchen table. Tijuanna Clemons’ own inner gratitude for life’s gifts shines through her character, infusing Bertha with a homespun humor that justifies her line that laughter is the best way “to know you’re alive.”

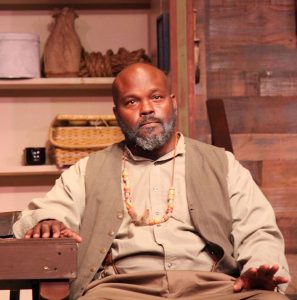

Seth and Bertha’s  comfy boardinghouse is filled with a handful of intriguing, damaged residents. The one who’s been there the longest is Bynum, a metaphysical bench philosopher possessed of clairvoyance and a penchant for backwater Louisiana voodoo, and he’s in search of some supernatural “shining man” he’s seen walking in the nearby woods. Bynum is brought to life on the Foulds Theatre stage by Cicero McCarter,

comfy boardinghouse is filled with a handful of intriguing, damaged residents. The one who’s been there the longest is Bynum, a metaphysical bench philosopher possessed of clairvoyance and a penchant for backwater Louisiana voodoo, and he’s in search of some supernatural “shining man” he’s seen walking in the nearby woods. Bynum is brought to life on the Foulds Theatre stage by Cicero McCarter,  who is quickly emerging as a formidable dramatic actor with mad, crazy skills. He dominates in his scenes, bending both the other characters and the audience to his indomitable will.

who is quickly emerging as a formidable dramatic actor with mad, crazy skills. He dominates in his scenes, bending both the other characters and the audience to his indomitable will.

Bynum finds his opposite in the earthly, rather randy Jeremy, a young man with big dreams of escaping the drudgery of menial labor on a road construction crew by playing music on his guitar. He’s portrayed by Kris Reid (another cast member who is making his stage debut), who does a terrific job of conveying the  irresponsible, skirt chasing attributes you’d expect to find in an up-and-coming blues musician in the decade leading up to World War I – much to Seth’s vexation and disapproval.

irresponsible, skirt chasing attributes you’d expect to find in an up-and-coming blues musician in the decade leading up to World War I – much to Seth’s vexation and disapproval.

Katherine Oni (a recent CHANGE graduate who debuted in George Wolfe’s The Colored Museum) portrays Mattie, a sad romantic in search of a loyal man who will love her to the end of times, with Ruth Augustin (making her Alliance for the Arts debut) playing Molly, a deeply cynical woman of the world whose first order of business is to protect herself and heart from men of means who want to trifle with both.

All of the residents’ hopes and fears, desires and needs congeal with the arrival of Loomis, an emotionally dark and brooding man played to such chilling effect by Lemec Bernard that it’s almost impossible to believe that Joe Turner represents his theater world debut. Tall and physically imposing, Bernard’s Loomis doesn’t just loom over the other actors on stage. His “wild-eyed, mean-looking” persona serves as catalyst for

All of the residents’ hopes and fears, desires and needs congeal with the arrival of Loomis, an emotionally dark and brooding man played to such chilling effect by Lemec Bernard that it’s almost impossible to believe that Joe Turner represents his theater world debut. Tall and physically imposing, Bernard’s Loomis doesn’t just loom over the other actors on stage. His “wild-eyed, mean-looking” persona serves as catalyst for  much of the action in this play and he’s the perfect antithesis to the otherworldly Bynum, who becomes obsessed with the possibility that Loomis could very well be his shining man.

much of the action in this play and he’s the perfect antithesis to the otherworldly Bynum, who becomes obsessed with the possibility that Loomis could very well be his shining man.

Each of these characters is searching for something, whether it is financial security, spirituality, lost love, adventure or, as in Loomis’ case, a missing relative.  But this search is only part of the effort to discover and give voice to their individual songs (or in more modern parlance, their truth). As each boardinghouse resident and even the proprietors ultimately discover, the only way to pursue the future is by embracing the past. And for African Americans seeking to escape the oppression, violence and lack of opportunity in the turn-of-the-2oth-century South that meant

But this search is only part of the effort to discover and give voice to their individual songs (or in more modern parlance, their truth). As each boardinghouse resident and even the proprietors ultimately discover, the only way to pursue the future is by embracing the past. And for African Americans seeking to escape the oppression, violence and lack of opportunity in the turn-of-the-2oth-century South that meant  coming to terms with slavery and their African heritage. And this is underscored in the closing scene in Act One, when everyone in the boarding house except Loomis spontaneously break into a lively, loud and high-spirited “juba,” a Ring Shout song and dance from central/west Africa in which one individual (here, Bynum) sets the tempo by banging a cane or staff and singing lyrics that the dancers answer in

coming to terms with slavery and their African heritage. And this is underscored in the closing scene in Act One, when everyone in the boarding house except Loomis spontaneously break into a lively, loud and high-spirited “juba,” a Ring Shout song and dance from central/west Africa in which one individual (here, Bynum) sets the tempo by banging a cane or staff and singing lyrics that the dancers answer in  call-and-response fashion.

call-and-response fashion.

It’s not August Wilson’s intent in Joe Turner to have each of his characters discover their song, find their voice or speak their truth. It’s sufficient to merely set the stage for greater introspection and open conversation about the ways in which the past affects both the present and the future, particularly in matters of race. But Wilson does complete the character arc in  the case of Loomis, and the explosive denouement comes when he finally finds what he’s been looking for in the form of Cantrella Canady.

the case of Loomis, and the explosive denouement comes when he finally finds what he’s been looking for in the form of Cantrella Canady.

Canady’s character, Martha, is referred to throughout the play like the distant report of thunder and drop in temperature associated with an approaching storm.  In a true sense, the first act and a half of Joe Turner has been building and building and building to this moment, and sure enough, Canady’s Martha bursts on the stage with tornadic force. You won’t read here what happens next. To find that you, you have to buy a ticket and watch the drama unfold for yourself. But suffice it to say that the exchange that ensues between

In a true sense, the first act and a half of Joe Turner has been building and building and building to this moment, and sure enough, Canady’s Martha bursts on the stage with tornadic force. You won’t read here what happens next. To find that you, you have to buy a ticket and watch the drama unfold for yourself. But suffice it to say that the exchange that ensues between Bernard’s Loomis and Canady’s Martha is so astonishing, so intense and so emotionally charged that not only does the audience find itself spellbound, but so do the other on-stage characters. It’s really a moment that only really good theatrical playwriting, acting and directing can produce, and it’s on stage in the Foulds Theatre for all to see.

Bernard’s Loomis and Canady’s Martha is so astonishing, so intense and so emotionally charged that not only does the audience find itself spellbound, but so do the other on-stage characters. It’s really a moment that only really good theatrical playwriting, acting and directing can produce, and it’s on stage in the Foulds Theatre for all to see.

Before closing, shout-outs are in order not only to Sonya McCarter for inspired direction and the mentorship (and prayers, no doubt) necessary to wring such amazing performances of difficult material from neophyte actors, but to the supporting performances delivered by Jim Yarnes (as Selig), Rozaria Brown (as Loomis’ 11-year-old daughter Zonia) and

Before closing, shout-outs are in order not only to Sonya McCarter for inspired direction and the mentorship (and prayers, no doubt) necessary to wring such amazing performances of difficult material from neophyte actors, but to the supporting performances delivered by Jim Yarnes (as Selig), Rozaria Brown (as Loomis’ 11-year-old daughter Zonia) and  Kavon Simmons (as the endearing heartfelt Reuben), who ably facilitated and contrasted with the play’s central themes and main action.

Kavon Simmons (as the endearing heartfelt Reuben), who ably facilitated and contrasted with the play’s central themes and main action.

True theater-goers should NEVER, EVER miss an opportunity to see an August Wilson play, and this is no exception. In fact, this production is so noteworthy not only because it provides insight into the black experience and race relations even today, but because it also introduces into  the Southwest Florida theater scene a new and talented crop of newbie thespians.

the Southwest Florida theater scene a new and talented crop of newbie thespians.

Welcome aboard.

March 15, 2019.

RELATED POSTS.

- ‘Joe Turner’ most spellbinding, emotionally rich of August Wilson’s Century Cycle plays

- ‘Joe Turner’ play dates, times and ticket info

Spotlight on Cantrella Canady, who plays Martha

Spotlight on Cantrella Canady, who plays Martha- Spotlight on Jim Yarnes, who plays peddler Rutherford Selig

- Spotlight on Cicero McCarter, who plays rootworker Bynum Walker

- Spotlight on Katherine Oni, who plays tenant Mattie Campbell

- Cast of ‘Joe Turner’ dominated by newcomers

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.