Lab’s ‘Crucible’ product of savvy direction, inspired production and break-out performances

Arthur Miller’s allegorical play The Crucible opened this past weekend at Lab Theater. The play featured predictably powerful portrayals by Steven Coe, TJ Albertson and Paul Graffy, but the audiences who caught these shows witnessed break-out performances by two relative newcomers, Kinley Gomez and Imani Lee

Arthur Miller’s allegorical play The Crucible opened this past weekend at Lab Theater. The play featured predictably powerful portrayals by Steven Coe, TJ Albertson and Paul Graffy, but the audiences who caught these shows witnessed break-out performances by two relative newcomers, Kinley Gomez and Imani Lee  Williams.

Williams.

Gomez plays Abigail Williams, the 17-year-old niece of Salem’s pastor, Reverend Samuel Parris (played by Casey Davis). Before the timeline of the play, Abigail worked in the home of John and Elizabeth Proctor (portrayed by Steven Coe and Imani Lee Williams). But Elizabeth Proctor insisted that she be dismissed after discovering that her  husband and Abigail had an affair right under her nose.

husband and Abigail had an affair right under her nose.

Whether she seduced him or John stole her innocence, Abigail’s sexual experience and liberation has made her the “it” girl among her peers – in a Regina George (Rachel McAdams, Mean Girls), Heather Chandler (Kim Walker, Heathers), Kathryn Merteuil (Sarah Michelle Gellar, Cruel Intentions) sort of way. Living once again in her uncle’s house, she leads a group of young girls that includes her cousin, Betty  (marvelously portrayed by Isabel Isenhower), the Right Reverend’s slave Tituba (mystically played by Melanie Payne), and her friends, Mercy Lewis (Emmie Spiller) and Mary Warren (Ruthgena Augustin) in a “lascivious dance to wanton ditties” around a campfire in the forest.

(marvelously portrayed by Isabel Isenhower), the Right Reverend’s slave Tituba (mystically played by Melanie Payne), and her friends, Mercy Lewis (Emmie Spiller) and Mary Warren (Ruthgena Augustin) in a “lascivious dance to wanton ditties” around a campfire in the forest.

Many varieties of same-sex dance were permitted in 1692 Salem. Boisterous or sensual polyrhythmic dance was not among them. This type of dance was not only considered scandalous, it was deemed sacrilegious. That’s because it distracted the mind from its proper focus on God,  undermined the primacy of work, and led potentially (if not invariably) to promiscuity and sinfulness (think Daughter of Sion from Isaiah 3:16).

undermined the primacy of work, and led potentially (if not invariably) to promiscuity and sinfulness (think Daughter of Sion from Isaiah 3:16).

Revered Parris catches Betty, Abigail and their posse in the act. In fact, two of the young women are caught dancing in the nude. While an adult caught engaging in un-sanctioned dance would typically only be subject to a monetary fine, Betty and a friend are overtaken with such fear over the punishment that  could be meted out (transgressions of community standards in Puritanical Massachusetts included such Draconian measures as the bilbo, wooden stocks, branding, maiming and the dreaded Scarlett Letter) that they fall into catatonic states. That provides Abigail with just what she needs to escape her own punishment. She tells her uncle that some women in the town placed a spell on them.

could be meted out (transgressions of community standards in Puritanical Massachusetts included such Draconian measures as the bilbo, wooden stocks, branding, maiming and the dreaded Scarlett Letter) that they fall into catatonic states. That provides Abigail with just what she needs to escape her own punishment. She tells her uncle that some women in the town placed a spell on them.  He seizes on the explanation. Why not, as it exonerates him of responsibility for his own failings as a parent and preacher.

He seizes on the explanation. Why not, as it exonerates him of responsibility for his own failings as a parent and preacher.

Past productions of The Crucible have cast Abigail Williams as either an impish brat or a sinister harlot. By contrast, Annette Trossbach and her directorial team ascribe to Abigail a far more dynamic motivation and mindset. Seeing the hysteria with which the pastor, Reverend John Hale (TJ Albertson) and the townspeople react to the specter of witchcraft,  Abigail suddenly and unexpectedly discovers a power to manipulate the people around her that she’d never before experienced and certainly didn’t enjoy in the situation with John and Elizabeth Proctor.

Abigail suddenly and unexpectedly discovers a power to manipulate the people around her that she’d never before experienced and certainly didn’t enjoy in the situation with John and Elizabeth Proctor.

This is not just an ingenious slant on a character who has been interpreted for more than six decades. It infuses the entire production with an element of realism that updates The Crucible and gives it a sobering  modern application. In Trossbach and her co-directors iteration, Abigail Williams is neither brat nor vengeful harlot. Rather, a smart and ruthless opportunist, she becomes the progenitor of a groupthink that culminates in mass hysteria!

modern application. In Trossbach and her co-directors iteration, Abigail Williams is neither brat nor vengeful harlot. Rather, a smart and ruthless opportunist, she becomes the progenitor of a groupthink that culminates in mass hysteria!

Groupthink is a term coined in 1972 by a psychologist  named Irving L. Janis to refer to a “psychological drive for consensus at any cost that suppresses dissent and appraisal of alternatives in cohesive decision-making groups.” It’s a real phenomenon, dating back to the Middle Ages and continuing to this day. In fact, John Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health has documented no less than 70 distinct outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness between 1973 and 1993 alone, 34 of which occurred in the United States, with symptoms including hyperventilation, fainting, stomach pains, nausea, numbness, tingling and muscle twitching – all in evidence in the

named Irving L. Janis to refer to a “psychological drive for consensus at any cost that suppresses dissent and appraisal of alternatives in cohesive decision-making groups.” It’s a real phenomenon, dating back to the Middle Ages and continuing to this day. In fact, John Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health has documented no less than 70 distinct outbreaks of mass psychogenic illness between 1973 and 1993 alone, 34 of which occurred in the United States, with symptoms including hyperventilation, fainting, stomach pains, nausea, numbness, tingling and muscle twitching – all in evidence in the  play.

play.

It’s one thing to conceive and envision such a construction. It’s another to find an actor capable of convincingly pulling it off. Kinley Gomez walks the fine line demanded by this characterization with the deftness of a Nik Wollenda or, to be gender correct, Maria Spelterini. She’s spectacular in the role.

For example,  at the very outset of Act I Scene 1, we raptly watch Abigail persuade her friends Mercy Lewis (Emmie Spiller) and Mary Warren (Ruthgena Augustin) to go along with her allegations. And when her cousin threatens to jump ship by jumping out a window, she doesn’t just throw the poor girl to the ground. Abigail literally slaps some sense into her startled cousin, effectively quelling any dissent coming from her or anyone else in their cohesive, tightknit little group.

at the very outset of Act I Scene 1, we raptly watch Abigail persuade her friends Mercy Lewis (Emmie Spiller) and Mary Warren (Ruthgena Augustin) to go along with her allegations. And when her cousin threatens to jump ship by jumping out a window, she doesn’t just throw the poor girl to the ground. Abigail literally slaps some sense into her startled cousin, effectively quelling any dissent coming from her or anyone else in their cohesive, tightknit little group.

At this junction,  Abigail is far from invincible. But her invulnerability evolves exponentially as she coolly watches and calmly listens to the adults in the room embrace and fall prey to the mass hysteria associated with having witches in their midst. Gomez signals the growing awareness of her newfound power to the audience without uttering a word. She conveys this dawning realization solely through her

Abigail is far from invincible. But her invulnerability evolves exponentially as she coolly watches and calmly listens to the adults in the room embrace and fall prey to the mass hysteria associated with having witches in their midst. Gomez signals the growing awareness of her newfound power to the audience without uttering a word. She conveys this dawning realization solely through her  piercing eyes and haughty bearing, which makes her machinations all the more convincing and scary as hell.

piercing eyes and haughty bearing, which makes her machinations all the more convincing and scary as hell.

Gomez saves the best for last. That comes in Act 2, Scene 1 when, as her carefully constructed canard threatens to dissolve under the accusations of her friend, Mary Warren, and John Proctor’s admission that he committed adultery with Abigail (which, by the way, was punishable by death in 1692 Salem), she and her squad convince Deputy Governor Danforth (chillingly portrayed by Paul Graffy), Judge  Hawthorne (Art Keen) and everyone else at the trial with the exception of Rev. Hale that they could see Mary’s “familiar” – a bird flying around the church. Pointing toward the rafters as she and her sidekicks huddle together on the edge of the stage, Gomez is so cold, calculating and manipulative that she squarely places herself in the company of the likes of Sharon Stone (Basic Instinct), Renee Zellweger (Diabolical) and Charlize

Hawthorne (Art Keen) and everyone else at the trial with the exception of Rev. Hale that they could see Mary’s “familiar” – a bird flying around the church. Pointing toward the rafters as she and her sidekicks huddle together on the edge of the stage, Gomez is so cold, calculating and manipulative that she squarely places herself in the company of the likes of Sharon Stone (Basic Instinct), Renee Zellweger (Diabolical) and Charlize  Theron (Monster).

Theron (Monster).

Kinley burst onto the theatrical scene last season in The Vagina Monologues last season, but based upon her performance in The Crucible, this young actor has a bright future in community and even equity theater.

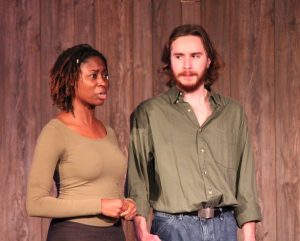

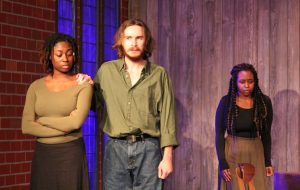

Imani Lee Williams was also on the Lab boards last season as Jo in The Legend of Georgia McBride.  In The Crucible, she too turns in a break-out performance – although her role as Elizabeth Proctor calls for a completely different and far more restrained execution.

In The Crucible, she too turns in a break-out performance – although her role as Elizabeth Proctor calls for a completely different and far more restrained execution.

Elizabeth Proctor is a moral, Christian woman. But she’s also cold as a witch’s …. – even before discovering her husband’s infidelity. Afterwards, she traverses all the expected emotions and stages of grief one  would expect following such a betrayal, ranging from self-righteousness anger to self-recrimination and fear. It’s difficult enough (if not impossible) for a woman to forgive her husband’s infidelity in 2019, never mind in Puritanical Salem in 1692, but Williams is up to the challenge. She’s superb in the role of an aggrieved wife, rebuking her husband when he objects to her suspiciousness by telling him “then let you not earn it.”

would expect following such a betrayal, ranging from self-righteousness anger to self-recrimination and fear. It’s difficult enough (if not impossible) for a woman to forgive her husband’s infidelity in 2019, never mind in Puritanical Salem in 1692, but Williams is up to the challenge. She’s superb in the role of an aggrieved wife, rebuking her husband when he objects to her suspiciousness by telling him “then let you not earn it.”

Interestingly,  Elizabeth Proctor tries to warn her husband that Abigail wants her dead so that the girl can take her place by his side and in his bed. That’s certainly a plausible interpretation of what happens in the play. First, Abigail induces Mary Warren to knit and give Elizabeth a poppet containing a concealed pin. Then she accuses her of witchcraft, claiming that the poppet is a voodoo doll and indicia of her guilt. But within the context of this production,

Elizabeth Proctor tries to warn her husband that Abigail wants her dead so that the girl can take her place by his side and in his bed. That’s certainly a plausible interpretation of what happens in the play. First, Abigail induces Mary Warren to knit and give Elizabeth a poppet containing a concealed pin. Then she accuses her of witchcraft, claiming that the poppet is a voodoo doll and indicia of her guilt. But within the context of this production,  it’s equally plausible that Elizabeth Proctor is merely collateral damage. Abigail Williams wants her dead not so that she can take her place, but rather to punish John Proctor for his coldhearted rejection – a more dastardly and malicious outcome.

it’s equally plausible that Elizabeth Proctor is merely collateral damage. Abigail Williams wants her dead not so that she can take her place, but rather to punish John Proctor for his coldhearted rejection – a more dastardly and malicious outcome.

Under either construction, Elizabeth Proctor is now a woman who, in spite of her innate goodness and Godliness, finds herself caught in a vice of religion and politics. Still, she’s not a mere powerless pawn. She gets to decide how to respond to the situation in which she  finds herself, ultimately taking responsibility for the role she played in driving her husband into the arms of another lover (“I counted myself so plain, so poorly made, no honest love could come to me! Suspicion kissed you when I did; I never knew how I should say my love. It were a cold house I kept!”) and in giving

finds herself, ultimately taking responsibility for the role she played in driving her husband into the arms of another lover (“I counted myself so plain, so poorly made, no honest love could come to me! Suspicion kissed you when I did; I never knew how I should say my love. It were a cold house I kept!”) and in giving  him the freedom to decide his own fate. In this moment, Williams shines brightest, quietly conveying her character’s dignity and grace.

him the freedom to decide his own fate. In this moment, Williams shines brightest, quietly conveying her character’s dignity and grace.

I’ve had the good fortune to see Steven Coe, TJ Albertson and Paul Graffy in a number of disparate roles. Their performances in The Crucible are individually and collectively special. Coe once again reprises  the role of victim, this time as a flawed man who, because he is essentially good and decent, finds to his chagrin that truth does not necessarily prevail over lies and deceit. Albertson is a picture of exasperation as a priest who discovers that facts and evidence are no match for superstition, emotion and hysteria. And Graffy is chilling as an officious politician who’s more concerned with power and perception than the rule of law.

the role of victim, this time as a flawed man who, because he is essentially good and decent, finds to his chagrin that truth does not necessarily prevail over lies and deceit. Albertson is a picture of exasperation as a priest who discovers that facts and evidence are no match for superstition, emotion and hysteria. And Graffy is chilling as an officious politician who’s more concerned with power and perception than the rule of law.

What also makes this production special are the quality performances turned in by The Crucible’s supporting cast. From top to bottom, each makes an excellent and important contribution to the overall product on the stage, vis: Tamicka Armstrong as Sarah Good, Patrick Ashton as Giles Corey, Ruthgena Augustin as Mary Warren, Casey Davis in the role of Reverend Parris, Mike Dinko

What also makes this production special are the quality performances turned in by The Crucible’s supporting cast. From top to bottom, each makes an excellent and important contribution to the overall product on the stage, vis: Tamicka Armstrong as Sarah Good, Patrick Ashton as Giles Corey, Ruthgena Augustin as Mary Warren, Casey Davis in the role of Reverend Parris, Mike Dinko  as Francis Nurse, Isabel Isenhower as Betty Parris, Heather Johnson as Rebecca Nurse, Corey T. Kane as Marshall Herrick, Art Keen in the role of Judge Hathorne, Todd Lyman as Thomas Putnam, Lauren Miller as Ann Putnam, Elizabeth Mora as Susanna Walcott, Melanie Payne at Tituba, Daniel Sabiston and Emarie Spiller as Mercy Lewis. Compliments to the unsung heroes of this show, as well:

as Francis Nurse, Isabel Isenhower as Betty Parris, Heather Johnson as Rebecca Nurse, Corey T. Kane as Marshall Herrick, Art Keen in the role of Judge Hathorne, Todd Lyman as Thomas Putnam, Lauren Miller as Ann Putnam, Elizabeth Mora as Susanna Walcott, Melanie Payne at Tituba, Daniel Sabiston and Emarie Spiller as Mercy Lewis. Compliments to the unsung heroes of this show, as well:  Assistant Director Kendra Weaver, Stage Manager Misha Polomsky, Production Coordinator Kristen Wilson, Technical Direction and Lighting Designer Jonathan Johnson and the understudies, Tamicka Armstrong, Mark King, Summer Meade and Anne Reed.

Assistant Director Kendra Weaver, Stage Manager Misha Polomsky, Production Coordinator Kristen Wilson, Technical Direction and Lighting Designer Jonathan Johnson and the understudies, Tamicka Armstrong, Mark King, Summer Meade and Anne Reed.

The themes and allegorical content of The Crucible will be dealt with in a subsequent review. But for now, if you’re a fan of savvy direction, inspired production and stellar acting, see this play. It’ll be among  the quickest three hours you’re ever going to spend.

the quickest three hours you’re ever going to spend.

September 24, 2019.

RELATED POSTS.

- Lab Theater marks 100th production with ‘The Crucible’

‘Crucible’ play dates, times and ticket info

‘Crucible’ play dates, times and ticket info- Spotlight on actor Steven Coe

- Spotlight on actor Paul Graffy

- Spotlight on actor Imani Lee Williams

- Spotlight on actor TJ Albertson

- Spotlight on actor Todd Lyman

- Spotlight on actor Lauren Miller

- Spotlight on actor Heather McLemore Johnson

- Spotlight on actor Mike Dinko

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.