Jenness Cortez

Genre: Realist

Media: Acrylics on mahogany panel

Gallery: DeBruyne Fine Art

Website: http://www.cortezart.com

Facebook: No

Her Art:

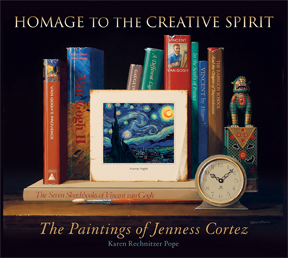

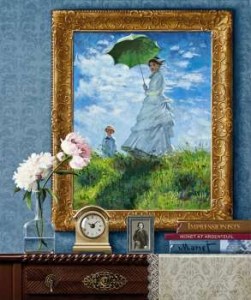

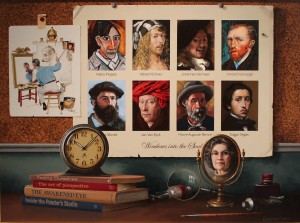

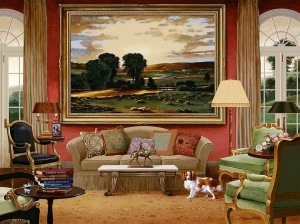

Her current series of paintings is titled Homage to the Creative Spirit. Each is a still life that revolves around an iconic masterpiece that has touched Cortez’s heart and soul. Cortez places the painting in a lush interior and surrounds it with objects that make allegorical and metaphorical reference to the artist, his genre, and period during which he created the work. The result is a mindboggling combination of impeccable workwomanship, art history, and riddles worthy of The Mentalist.

Her current series of paintings is titled Homage to the Creative Spirit. Each is a still life that revolves around an iconic masterpiece that has touched Cortez’s heart and soul. Cortez places the painting in a lush interior and surrounds it with objects that make allegorical and metaphorical reference to the artist, his genre, and period during which he created the work. The result is a mindboggling combination of impeccable workwomanship, art history, and riddles worthy of The Mentalist.

The artist and her husband (center) talk with collector with homage to Wyeth's Christina's World in background.

Cortez is a member of a select group of artists sometimes called photorealists (see below). Only a handful of modern day painters have the eye, technical skill and intestinal fortitude to create photorealistic works of art because each painting takes months to research, weeks to draw, and upwards of two to three years to complete. Consequently, it comes as no surprise that Jenness Cortez’s body of work is as limited in number as it is broad in scope.

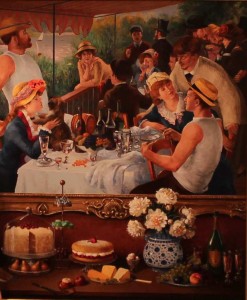

To create each homage requires a virtuosity reminiscent of DaVinci or Michelangelo. Because she is creating a still life that incorporates a masterwork from the past, Cortez must not only blend portraiture, figurative work, landscape painting and equestrian art into the motif of her still life, she must express a fundamental comprehension of the concerns and goals of the artists who pioneered the classical, impressionist, expressionist and magical realist movements. She does not merely copy Renoir, Holbein, David, Manet, van Gogh, Inness, Wyeth or Rockwell. She pays tribute to the styles of art they created and advanced.

To create each homage requires a virtuosity reminiscent of DaVinci or Michelangelo. Because she is creating a still life that incorporates a masterwork from the past, Cortez must not only blend portraiture, figurative work, landscape painting and equestrian art into the motif of her still life, she must express a fundamental comprehension of the concerns and goals of the artists who pioneered the classical, impressionist, expressionist and magical realist movements. She does not merely copy Renoir, Holbein, David, Manet, van Gogh, Inness, Wyeth or Rockwell. She pays tribute to the styles of art they created and advanced.

But even that isn’t enough for Cortez. She then imports into her compositions objects that would be found in the artist’s atelier or in the day, time and geographical vicinity in which the work was rendered. Whether or not you possess a background in art history, you can while away hours trying to divine why Cortez included each object in her composition, and it is this puzzle-pieces aspect that makes her paintings so rivetingly intriguing.

But even that isn’t enough for Cortez. She then imports into her compositions objects that would be found in the artist’s atelier or in the day, time and geographical vicinity in which the work was rendered. Whether or not you possess a background in art history, you can while away hours trying to divine why Cortez included each object in her composition, and it is this puzzle-pieces aspect that makes her paintings so rivetingly intriguing.

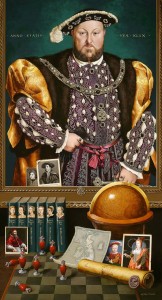

Take for example The Game Changer (left), in which a Hans Holbein portrait of King Henry VIII hangs in the background. The tendency when looking at this painting is to get lost in portraiture or the intricate detail of Henry’s billowy, purple garb. But then you notice the globe, books, photographs, map and chess pieces, a few laying on their side. Each object references either Holbein or Henry and the period in which they lived, but Cortez challenges the viewer to discover their significance to the artist, his subject and the day and age in which both lived.

Take for example The Game Changer (left), in which a Hans Holbein portrait of King Henry VIII hangs in the background. The tendency when looking at this painting is to get lost in portraiture or the intricate detail of Henry’s billowy, purple garb. But then you notice the globe, books, photographs, map and chess pieces, a few laying on their side. Each object references either Holbein or Henry and the period in which they lived, but Cortez challenges the viewer to discover their significance to the artist, his subject and the day and age in which both lived.

“Every painting begins with a vision seen in the artist’s mind,” Cortez says of her process. “Sometimes the finished piece appears in the mind full-blown, and at other times it is amorphous––yet with some beguiling character that begs to be developed. In either case, between that first inspiration and the finished painting lie hours of research, thousands of choices and, of course, the great joy of painting. The process is organic. Even with a well-conceived composition in place, the painting has a life of its own and the best ones surprise even the artist with twists and turns that outshine the most clever of plans. It’s as if the creative spirit insinuates itself into the work, wanting to serve its own best interest with solutions that far exceed the artist’s original, limited vision.”

“Every painting begins with a vision seen in the artist’s mind,” Cortez says of her process. “Sometimes the finished piece appears in the mind full-blown, and at other times it is amorphous––yet with some beguiling character that begs to be developed. In either case, between that first inspiration and the finished painting lie hours of research, thousands of choices and, of course, the great joy of painting. The process is organic. Even with a well-conceived composition in place, the painting has a life of its own and the best ones surprise even the artist with twists and turns that outshine the most clever of plans. It’s as if the creative spirit insinuates itself into the work, wanting to serve its own best interest with solutions that far exceed the artist’s original, limited vision.”

Executive Director of the Palos Verdes Art Center Robert Yassin calls Jenness Cortez one of the world’s most eloquent and successful visual conversationalists. “All art is a dialogue, a conversation through the medium of the artwork between the artist and the viewer,” Yassin postulates. “It is the level of that dialogue that establishes the intrinsic value of a given work. Among the many characteristics of a real work of art, two are most significant and define both the quality and significance of the dialogue. The first is that what the artist is saying must be meaningful;

Executive Director of the Palos Verdes Art Center Robert Yassin calls Jenness Cortez one of the world’s most eloquent and successful visual conversationalists. “All art is a dialogue, a conversation through the medium of the artwork between the artist and the viewer,” Yassin postulates. “It is the level of that dialogue that establishes the intrinsic value of a given work. Among the many characteristics of a real work of art, two are most significant and define both the quality and significance of the dialogue. The first is that what the artist is saying must be meaningful;  the second, that it is clearly communicated and understood. In Cortez’ paintings, both criteria are more than fully met. The work talks to us at many levels and creates in us a sense of both understanding and well being. This happens because there is nothing arbitrary in Cortez’ paintings. The choice of the painting reproduced, the elements surrounding it, the space the elements occupy, the lighting, the color, everything is carefully selected and orchestrated following a fully articulated plan determined by the artist . . . The paintings of Jenness Cortez make my heart sing.”

the second, that it is clearly communicated and understood. In Cortez’ paintings, both criteria are more than fully met. The work talks to us at many levels and creates in us a sense of both understanding and well being. This happens because there is nothing arbitrary in Cortez’ paintings. The choice of the painting reproduced, the elements surrounding it, the space the elements occupy, the lighting, the color, everything is carefully selected and orchestrated following a fully articulated plan determined by the artist . . . The paintings of Jenness Cortez make my heart sing.”

By masterfully presenting iconic works of art in unexpected modern settings, Jenness Cortez inspires us to see differently––to rediscover and revalue our own creative power in everyday life.

Valuation

"The Game Changer" (right) sold even before the opening of Cortez's solo exhibition at DeBruyne Fine Art in January, 2011.

These are legacy pieces, artworks that can easily serve as the cornerstone of an important fine art collection. They are paintings a collector admires and keeps a lifetime and then passes to his or her children and grandchildren. That’s why very few photorealist works come up for resale, whether at auction or in private transactions.

That being said, it is not surprising that the list of people who have collected Cortez include heads of state and discerning collectors worldwide. This elite group includes President Bill Clinton, former President Ronald Reagan, HRH Queen Elizabeth II, Ambassador True Davis, Governors Hugh Carey and George Pataki, Congressman Gerald Soloman, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Alexander, Edgar Bronfman, Virginia Kraft Payson, Henry Kravis, Ogden Mills Phipps, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, Jerry Weintraub and Atlanta Braves general manager John Schuerholz.

That being said, it is not surprising that the list of people who have collected Cortez include heads of state and discerning collectors worldwide. This elite group includes President Bill Clinton, former President Ronald Reagan, HRH Queen Elizabeth II, Ambassador True Davis, Governors Hugh Carey and George Pataki, Congressman Gerald Soloman, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Alexander, Edgar Bronfman, Virginia Kraft Payson, Henry Kravis, Ogden Mills Phipps, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, Jerry Weintraub and Atlanta Braves general manager John Schuerholz.

Cortez's shows are highly popular, as evidenced by the packed house at DeBruyne Fine Art for her opening night reception.

As these names imply, it not only takes a discerning eye but some serious coin to acquire a Jenness Cortez. But their value reflects not only the copious amount of time it takes to research, draw and complete each work, but the lifetime of training necessary to assimilate the style and genre of the underlying artwork she chooses to feature in these paintings.

Roxane Galati (center) talks with two guests at DeBruyne Fine Art with Cortez homage to Frederic Remington's "A Dash for the Timber" in background.

For example, she copies Jacques-Louis-David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Great St. Bernard (in Knight and King), Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair (in Civility and Power), and Edouard Manet’s The Races at Longchamp 1866 (in Manet’s Paris). But she was poised to reproduce these extraordinary equine masterpieces by the 20 year period between the mid-seventies and mid-nineties she spent concentrating on sports paintings that often contained powerful depictions of horses for which she drew comparisons to George Stubbs and Frederic Remington.

Similarly, she copies Wyeth’s Christina’s World (in The Brandywine Tradition), Peter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow (in January), and George Inness’ Peace and Plenty (in Plentitude and again in The Good Earth). But she was able to pull off these landscapes because she embarked in the mid-nineties upon a decade of study of landscape art, taking to heart the lessons taught by the 19th century Hudson River School and the Barbizon School painters.

In essence, her previous education, training and experience uniquely qualify her to render paintings that pay homage the masters who preceded her with a skill, understanding and empathy that few – if any – other living artists could replicate. And that is why these paintings are so valuable and why they are likely to appreciate significantly over time.

In essence, her previous education, training and experience uniquely qualify her to render paintings that pay homage the masters who preceded her with a skill, understanding and empathy that few – if any – other living artists could replicate. And that is why these paintings are so valuable and why they are likely to appreciate significantly over time.

Historical Note and Perspective

So what is photorealsim anyway? To answer this straightforward poser, we should enlist the help of Louis Meisel. Eric Cohler of American Art Collector conferred the title on Meisel of “eminence grise of photorealism.” (Vol. 32, June 2008, p. 58.) Meisel was the first to recognize the photorealism movement back in the ’60s, and he’s the one who accidentally gave the movement its name.

So what is photorealsim anyway? To answer this straightforward poser, we should enlist the help of Louis Meisel. Eric Cohler of American Art Collector conferred the title on Meisel of “eminence grise of photorealism.” (Vol. 32, June 2008, p. 58.) Meisel was the first to recognize the photorealism movement back in the ’60s, and he’s the one who accidentally gave the movement its name.

In an interview by Guggenheim curator Valerie Hillings and art history professor David Lubkin for Artmag in May of 2008, Meisel recalled showing works by Charlie Bell and a few others in his small Madison Avenue gallery back in 1969. “Village Voice critic Howard Smith asked me, ‘What are you going to call this group?’ I said, ‘I don’t know … they’re using the photograph, they’re being very open about it. It’s photographic realism. I don’t know. Photorealism? Does that sound good to you?'”

In an interview by Guggenheim curator Valerie Hillings and art history professor David Lubkin for Artmag in May of 2008, Meisel recalled showing works by Charlie Bell and a few others in his small Madison Avenue gallery back in 1969. “Village Voice critic Howard Smith asked me, ‘What are you going to call this group?’ I said, ‘I don’t know … they’re using the photograph, they’re being very open about it. It’s photographic realism. I don’t know. Photorealism? Does that sound good to you?'”

So now we know who coined the term, and when, but what is Photorealism? Maisel offers this 4-point definition:

The Photorealist uses a camera and photographs to gather information.

The Photorealist uses a camera and photographs to gather information.- She uses mechanical or semi-mechanical technology to transfer that information to the canvas.

- The Photorealist must have the technical ability to make the finished work appear photographic.

- The artist must have devoted at least five years to the development and exhibition of Photorealistic work.

Anyone can snap pictures, especially with a digital camera. Anyone can employ technology to transfer photographs or slides to a canvas or mahogany panel. But only an artist with the skill and virtuosity of a Georgia O’Keefe, Charlie Bell, Richard Estes or Jenness Cortez can make that image appear photographic.

Local Exhibitions

Her solo exhibition at DeBruyne Fine Art in January of 2012 marked her 11th solo show at DeBruyne. “I only have shows at DeBruyne,” Cortez notes. “The Naples art community has always supported my art, and I am very, very grateful for that.”

Her solo exhibition at DeBruyne Fine Art in January of 2012 marked her 11th solo show at DeBruyne. “I only have shows at DeBruyne,” Cortez notes. “The Naples art community has always supported my art, and I am very, very grateful for that.”

Education and Accomplishments

- Jenness Cortez was born in 1944 in Frankfort, Indiana.

- She received her B.F.A. at the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis.

- She apprenticed privately with noted Dutch painter Antonius Raemaekers.

- She later studied with Arnold Blanche at the Art Students League of New York.

- Her work is in numerous public and private collections the New York State Museum and SUNY Empire State College.

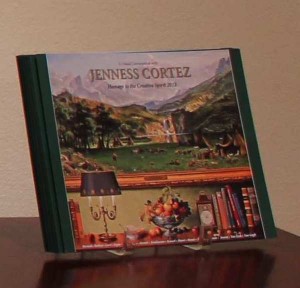

On April 5, 2011, AMI Publishers released Homage to the Creative Spirit, a retrospective of 54 of Cortez’s best works from the series by the same name with background and analysis provided by Dr. Karen Rechnitzer Pope, a Baylor University art historian, with a forward by Robert Yassin, former director of both the Indianapolis and Tucson Museums of Art.

On April 5, 2011, AMI Publishers released Homage to the Creative Spirit, a retrospective of 54 of Cortez’s best works from the series by the same name with background and analysis provided by Dr. Karen Rechnitzer Pope, a Baylor University art historian, with a forward by Robert Yassin, former director of both the Indianapolis and Tucson Museums of Art.- On May 15, 2012, the book was awarded the 2012 Independent Publishers “Outstanding Book of the Year” gold medal.

- According to Independent Publishers’ awards director Jim Barnes, the book exhibits “the courage and creativity necessary to take chances, break new ground, and bring about change––not only to the world of publishing––but to our society. The masterful realist paintings by Jenness Cortez and insightful commentary by Karen Rechnitzer Pope, represent the most heartfelt, unique, outspoken and experimental literary and creative achievement among our 5,023 entries.”

- The book is available at Amazon.com, at fine book sellers, and through the artist’s website.

Related Articles and Links

- Jenness Cortez painting pays tribute to Rockwell and two vanishing traditions (01-27-13)

- Book of Jenness Cortez paintings wins ‘Outstanding Book of the Year’ gold medal (05-16-12)

- Photorealist Jenness Cortez returns January 26 to Naples’ DeBruyne Fine Art (01-25-12)

Archived Articles

- Jenness Cortez solo exhibition opens at DeBruyne Fine Art January 27 (01-22-11)

- DeBruyne Fine Art’s Jenness Cortez is the penultimate photorealist (01-24-11)

- Photorealist Jenness Cortez, an artist with prowess and virtuosity (01-25-11)

- Cortez’s paintings are intelligent, richly researched and brilliantly executed (01-26-11)

- Jenness Cortez exhibition opens tonight at Naples’ DeBruynne Fine Art (01-27-11)

- Jenness Cortez reception and solo exhibition simply outstanding (01-28-11)

- Five reasons to see Jenness Cortez exhibition at DeBruyne Fine Art (01-29-11)

- Jenness Cortez’ ‘Homage to the Creative Spirit’ now out in book form (04-13-11)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.