‘NOA’ enigmatic film about the price of freedom

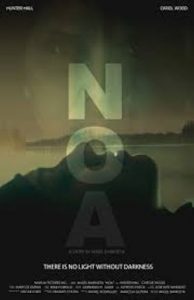

Among the short films to be screened this year by the Fort Myers Film Festival is NOA, a 15-minute film that filmmaker Angel Barroeta describes as “a spiritual journey, in a dystopian and chaotic society [that dives] deep into the dark side of humanity.” Barroeta places his film in the categories of drama, sci-fi, retro-futuristic and film noir.

Among the short films to be screened this year by the Fort Myers Film Festival is NOA, a 15-minute film that filmmaker Angel Barroeta describes as “a spiritual journey, in a dystopian and chaotic society [that dives] deep into the dark side of humanity.” Barroeta places his film in the categories of drama, sci-fi, retro-futuristic and film noir.

Beautifully shot without either dialogue or subtext, NOA opens with a rolled up rug being tossed from a van and coming to rest in the dirt and weeds alongside a desolate stretch of road. Inside is a body, presumably of a young woman, but only a glimpse of her hand and hair is provided before the camera cuts away to a darkened apartment where a pretty young lady slowly dresses in the gloom of her bedroom.

She is an urban dweller, presumably somewhere in America, but few clues are given as to where or when. The woman does not appear to be in any rush. In fact, there is an air of deliberateness in her movements and actions.

She is an urban dweller, presumably somewhere in America, but few clues are given as to where or when. The woman does not appear to be in any rush. In fact, there is an air of deliberateness in her movements and actions.

On  the street, she traverses a nightscape with no apparent concern or trepidation, passing graffiti tags professing “No Future, No Future” along the way. Given the film’s opening sequence, the viewer justifiably wonders whether she is about to be abducted, but that

the street, she traverses a nightscape with no apparent concern or trepidation, passing graffiti tags professing “No Future, No Future” along the way. Given the film’s opening sequence, the viewer justifiably wonders whether she is about to be abducted, but that  supposition is dispelled when she arrives at a building and is ushered inside by a shady looking character.

supposition is dispelled when she arrives at a building and is ushered inside by a shady looking character.

The woman is escorted to a severe-looking woman, and in spite of the lack of dialogue, it becomes clear  that the protagonist has arranged to get a passport and fake ID. But the price to be paid for her new identity is a steep one. She steps outside onto a balcony overlooking the cityscape, where she strips off all of her clothing. Back inside, she is led upstairs, where she subjects herself to sexual exploitation at the hands of an orgy of writhing male and female bodies.

that the protagonist has arranged to get a passport and fake ID. But the price to be paid for her new identity is a steep one. She steps outside onto a balcony overlooking the cityscape, where she strips off all of her clothing. Back inside, she is led upstairs, where she subjects herself to sexual exploitation at the hands of an orgy of writhing male and female bodies.

As the rolled up carpet is pushed from the moving van, the viewer suspects, perhaps even expects, that the girl is dead. Was the promise of a passport and new ID merely a ruse designed to lure the girl to her death, or did something go horribly wrong during the group rape? But no, in the end, she’s alive and as she peels back

As the rolled up carpet is pushed from the moving van, the viewer suspects, perhaps even expects, that the girl is dead. Was the promise of a passport and new ID merely a ruse designed to lure the girl to her death, or did something go horribly wrong during the group rape? But no, in the end, she’s alive and as she peels back  the carpet beneath blue skies, we see that the passport and ID have been shrink wrapped to her chest. A smile crosses her face as spies other young people, even children, gathered in the forest, welcoming her arrival. The message is clear.

the carpet beneath blue skies, we see that the passport and ID have been shrink wrapped to her chest. A smile crosses her face as spies other young people, even children, gathered in the forest, welcoming her arrival. The message is clear.  This is a new beginning and while her existence is likely to be fraught with difficulties, she’s going to be okay. She has a future. And it’s a future of her own choosing.

This is a new beginning and while her existence is likely to be fraught with difficulties, she’s going to be okay. She has a future. And it’s a future of her own choosing.

This film was screened during last December’s T.G.I.M. and  garnered a number of comments from the evening’s celebrity judges and audience members. Here’s what they said:

garnered a number of comments from the evening’s celebrity judges and audience members. Here’s what they said:

- Mainsail Productions owner and Emmy-winning videographer Ilene Safron Whitesman: “What price would you pay for freedom? On an individual level, don’t we all trade a part of ourselves for the promise of a better, more secure future? That job we hate. That spouse we despise. The list goes on and on.”

- Local stage, film and television actor Rachel Burttram Powers: “We’re living in a time when we’re hyperaware of the exploitation of women because of people coming forward in Hollywood and politics.”

Sunday morning Ask and Expert host Tom Conwell: “It’s that whole ‘me too’ thing,” making reference to men like Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, Charlie Rose, Bill O’Reilly and a legion of other power brokers in the entertainment and other industries who routinely threatened to deprive their victims of their futures in order to sexually exploit them or ensure their silence following a sexual assault.

Sunday morning Ask and Expert host Tom Conwell: “It’s that whole ‘me too’ thing,” making reference to men like Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, Charlie Rose, Bill O’Reilly and a legion of other power brokers in the entertainment and other industries who routinely threatened to deprive their victims of their futures in order to sexually exploit them or ensure their silence following a sexual assault.- Host Eric Raddatz felt that the film operated on an even more pervasive and insidious level. Pointing to an expose coming out that Wednesday in Florida Weekly, he saw a clear analogy in NOA to human trafficking, pointing out that Florida finds itself in the top three states in number of reported cases of human trafficking and sexual slavery each year.

“For those who are survivors of the death camps like Auschwitz, for those who are survivors of human trafficking and sexual abuse, is there a rebirth that comes after that?” Raddatz asked. “Is there life after that? What is life like after that? Are there smiles after that? Can there be smiles after that?”

“For those who are survivors of the death camps like Auschwitz, for those who are survivors of human trafficking and sexual abuse, is there a rebirth that comes after that?” Raddatz asked. “Is there life after that? What is life like after that? Are there smiles after that? Can there be smiles after that?”  A female audience member: “We’re actually pretty privileged. For us, living in the United States, it may not hit close to home. But elsewhere, in other places around the world, it’s a really common thing, an everyday thing. Normal.” For her, NOA

A female audience member: “We’re actually pretty privileged. For us, living in the United States, it may not hit close to home. But elsewhere, in other places around the world, it’s a really common thing, an everyday thing. Normal.” For her, NOA  provided an emotional portal into conditions which are unfamiliar for those of us lucky enough to be living in the United States.

provided an emotional portal into conditions which are unfamiliar for those of us lucky enough to be living in the United States.

And in that respect, NOA may indeed serve as a metaphor, not for the sacrifices we make to secure a better future or even for sexual exploitation or human trafficking, but for all the refugees forced to take on new identities in order to escape places in which “No Future” is really their stark reality. From this perspective, NOA provides insight into the mindset of a Columbian who leaves behind her home and material possessions to assume a new identity and life in a place like America to escape the murders and poverty  common in cities like Medellin, Valle del Cauca and Bogota. NOA invites us to empathize with refugees from places like Syria, Iraq, Turkey and adjoining countries who leave everything behind and endure indescribable hardships, including sexual exploitation, to escape civil war, political oppression and the abject poverty and absence of opportunity that

common in cities like Medellin, Valle del Cauca and Bogota. NOA invites us to empathize with refugees from places like Syria, Iraq, Turkey and adjoining countries who leave everything behind and endure indescribable hardships, including sexual exploitation, to escape civil war, political oppression and the abject poverty and absence of opportunity that  is part and parcel to such a widespread humanitarian crisis.

is part and parcel to such a widespread humanitarian crisis.

If this was truly the intent of the filmmakers, then NOA comes at an interesting time in U.S. politics, as political leaders and their constituents re-evaluate the role, if any, that this country will play in welcoming immigrants and displaced refugees.

There  is much to applaud in the film beyond its metaphorical themes. All three judges found the cinematography beautiful, the absence of dialogue compelling, and the acting extremely well done.

is much to applaud in the film beyond its metaphorical themes. All three judges found the cinematography beautiful, the absence of dialogue compelling, and the acting extremely well done.

“The final sequence of shots was really, really beautiful,” remarked Rachel Burttram Powers, who has performed in three independent films herself.  “When you see there is help for her and that her credentials are taped to her chest so that what’s she has gone through – which is really horrifying – was worth the price she paid … Well, this is definitely a movie I will think about tomorrow and the next day and the day after that.”

“When you see there is help for her and that her credentials are taped to her chest so that what’s she has gone through – which is really horrifying – was worth the price she paid … Well, this is definitely a movie I will think about tomorrow and the next day and the day after that.”

“You knew she didn’t want to be where she was,” added Ilene Safron Whitesman. “She was getting a passport out of there. The smile at the end said it all. When she saw the kids [in the forest], that  represented a new beginning.”

represented a new beginning.”

Tom Conwell summed up his own reaction to NOA with a single word – “cathartic.”

An audience member was equally intrigued by the enigmatic name that the filmmakers gave to their film. “No other alternative,” she offered. “No other answer.”

And  that about sums it up for millions of political refugees, displaced migrants, and illegal immigrants who seek asylum in foreign countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Great Britain and, yes, even the United States.

that about sums it up for millions of political refugees, displaced migrants, and illegal immigrants who seek asylum in foreign countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Great Britain and, yes, even the United States.

The film premieres on March 13 at the Miami Film Festival. The screening at FMff will only be its second film festival appearance. It plays in the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center during this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival

March 4, 2018.

March 4, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

- Fort Myers Film Festival to screen sensational new Ruth Bader Ginsburg doc

- ‘RBG’ doc filmmakers Betsy West and Julie Cohen in the frame

About the 8th Annual Fort Myers Film Festival

About the 8th Annual Fort Myers Film Festival- Fort Myers Film Festival to open with ‘Melody Makers’ rock doc

- Photographer Barrie Wentzell in the frame

- ‘Melody Makers’ director Leslie Ann Coles in the frame

- “What is Classic Rock’ is all about the music

- ‘Don’t Sell My Guitars’ love letter by filmmaker Lynn Montgomery to her dad

- ‘The Maestro’ looks at post-World War II Hollywood film composers

- The Maestro’s Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco in the frame

- ‘Let It Shine: The Story of the Women’s March SLO’

- ‘Kids News’ a tribute to Naples’ Judy Lawrence

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.