Q&A with Guerrilla Girl Frida Kahlo

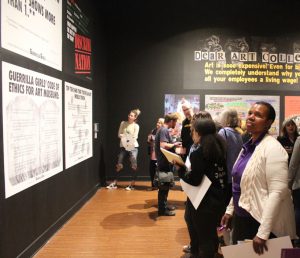

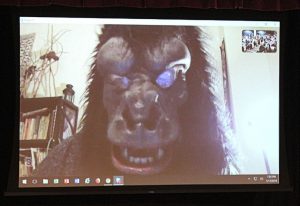

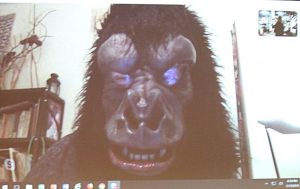

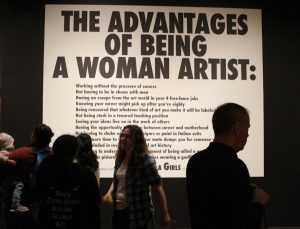

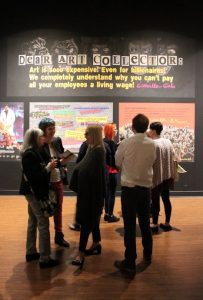

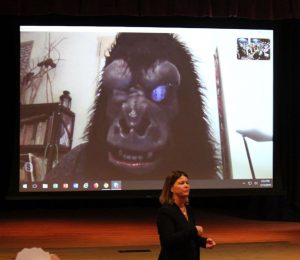

On view in the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Florida SouthWestern State College is GUERRILLA GIRLS: Rattling Cages Since 1985. Guerrilla Girl Frida Kahlo skyped in on the night of the show’s opening to field questions from the audience. While her identity remains a closely-guarded secret, her pithy remarks and observations reveal the woman beneath the guerrilla mask to be sharp, quick-witted, wry and singularly focused on the role of women in the arts.

On view in the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery on the Lee campus of Florida SouthWestern State College is GUERRILLA GIRLS: Rattling Cages Since 1985. Guerrilla Girl Frida Kahlo skyped in on the night of the show’s opening to field questions from the audience. While her identity remains a closely-guarded secret, her pithy remarks and observations reveal the woman beneath the guerrilla mask to be sharp, quick-witted, wry and singularly focused on the role of women in the arts.

Nine-year-old Ruby Swanson acknowledged the 900-pound guerrilla in the room, asking Frida what it’s like to be and represent the Guerrilla Girls.

Nine-year-old Ruby Swanson acknowledged the 900-pound guerrilla in the room, asking Frida what it’s like to be and represent the Guerrilla Girls.

“It’s kind of wonderful and it’s kind of hard,” Frida replied. “I’m extremely proud of the work that we’ve done  and I’ve been so since the very beginning. Every morning I wake up thinking about what we’re going to do next, not what we’ve done in the past. It’s very exciting. And in a way, it’s a dream come true. It’s nothing that I planned for, it is just something that happened and we ran with it and I haven’t looked back.”

and I’ve been so since the very beginning. Every morning I wake up thinking about what we’re going to do next, not what we’ve done in the past. It’s very exciting. And in a way, it’s a dream come true. It’s nothing that I planned for, it is just something that happened and we ran with it and I haven’t looked back.”

Another  audience member asked the Gurrilla Girl what inspired her to take on Frida Kahlo as her identity.

audience member asked the Gurrilla Girl what inspired her to take on Frida Kahlo as her identity.

“Back in the mid-80s, when our group started, the very first English language biography of Frida Kahlo came out and I was really taken by her personality,” she explained.

“Her work was not as well known then as it is now, and she was even less well known in the United States than she was in Mexico, where she was sort of an icon. In a way, I wanted people to think about her and know who she was, so I didn’t think about it for a second. I might have second thoughts now because I’m not Latina and it’s a more complicated thing now.

“Her work was not as well known then as it is now, and she was even less well known in the United States than she was in Mexico, where she was sort of an icon. In a way, I wanted people to think about her and know who she was, so I didn’t think about it for a second. I might have second thoughts now because I’m not Latina and it’s a more complicated thing now.  But it’s a choice I made 30 years ago. And Frida Kahlo has become more and more iconic and sometimes I just like to channel her energy, channel her outrageousness, and remember who she was.”

But it’s a choice I made 30 years ago. And Frida Kahlo has become more and more iconic and sometimes I just like to channel her energy, channel her outrageousness, and remember who she was.”

Asked if she’s ever been tempted to reveal her identity, Kahla gave an emphatic no.

“It’s  fun to have an alternative ego to jump into,” she chuckled. “Some days I’m myself. Some days I’m Frida Kahlo. I don’t think it’s really important who I am. You might be disappointed to find out who I am. Maybe it would even diminish the reputation of the Guerrilla Girls if our identities were revealed. It’s fun to retain the mystique. We might even be the person you’re going home with tonight. So wearing the mask is a great power, a great strategy and a great advantage for us.”

fun to have an alternative ego to jump into,” she chuckled. “Some days I’m myself. Some days I’m Frida Kahlo. I don’t think it’s really important who I am. You might be disappointed to find out who I am. Maybe it would even diminish the reputation of the Guerrilla Girls if our identities were revealed. It’s fun to retain the mystique. We might even be the person you’re going home with tonight. So wearing the mask is a great power, a great strategy and a great advantage for us.”

Another audience member wanted to know what is it like to work in a collective, to work collaboratively, for over 30 years.

Another audience member wanted to know what is it like to work in a collective, to work collaboratively, for over 30 years.

“Imagine being married to 50 different people for 30 years all at the same time,” Kahlo shot right back. “Anything that happens in a personal relationship has happened in our collective. But we really believe in our group, in agreeing to disagree, in trying to build consensus among ourselves, and trying to be as diverse  as possible.”

as possible.”

Posing a question on everyone’s mind, someone asked whether the Guerrilla Girls are artists.

“We’re all involved in the art world in some way,” Kahlo replied expansively. “The term artist is a little fluid. You can be creative as artists and as critics. All I can say is that all of the Guerrilla Girls are involved in the arts in some way.”

Recognizing  that Kahlo has been a Guerrilla Girl since the 1980s, one audience member wanted to know how much the Guerrilla Girls and the art world have changed over the past 30 years.

that Kahlo has been a Guerrilla Girl since the 1980s, one audience member wanted to know how much the Guerrilla Girls and the art world have changed over the past 30 years.

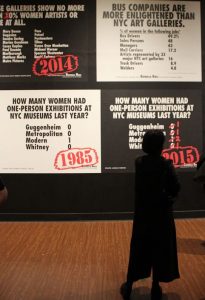

“One thing for sure is that the conscience of the art world has changed. No longer would anyone in power admit, at least openly, that you could write the history of art with only white male artists. There was a time when  literally all the experts in the art world thought that art history was an aristocracy. I think we’ve proved that that’s not true. That’s a huge, huge leap of knowledge. What hasn’t changed is the institutional structure of the art world, of museums, art galleries and even the structure of university art departments. It’s still white male dominated. So that’s what

literally all the experts in the art world thought that art history was an aristocracy. I think we’ve proved that that’s not true. That’s a huge, huge leap of knowledge. What hasn’t changed is the institutional structure of the art world, of museums, art galleries and even the structure of university art departments. It’s still white male dominated. So that’s what  we have to focus on changing. It’s not a question about empowering ourselves. We have what it takes. It’s the system that’s preventing us from recognition. So it’s the institutional structure of the art world that we really have to go after and change that.”

we have to focus on changing. It’s not a question about empowering ourselves. We have what it takes. It’s the system that’s preventing us from recognition. So it’s the institutional structure of the art world that we really have to go after and change that.”

Speaking of institutional  structure, an audience member was curious about why the Tate was willing to put on a Guerrilla Girl exhibit (in 2016) but neither MOMA nor any other major U.S. museums have exhibited them.

structure, an audience member was curious about why the Tate was willing to put on a Guerrilla Girl exhibit (in 2016) but neither MOMA nor any other major U.S. museums have exhibited them.

Kahlo’s answer was revealing. “The Brits and many other Europeans love to hear Americans criticize the U.S. Plus, British  and most European museums are state run. They’re not as driven by money or by wealth or philanthropy. They actually believe that when you have a problem, government should solve it rather than a rich person to possibly solve the problem.”

and most European museums are state run. They’re not as driven by money or by wealth or philanthropy. They actually believe that when you have a problem, government should solve it rather than a rich person to possibly solve the problem.”

Addressing the reticence of American museums, she added that “We really attack institutions and that makes American  institutions really nervous because of the impact on philanthropy. When donors get nervous, they pull their support and that is frightening to American museums.”

institutions really nervous because of the impact on philanthropy. When donors get nervous, they pull their support and that is frightening to American museums.”

So then, how do we go about changing the mindset of the directors, administrators and curators who run the museums and art institutions that fail to include female artists in their permanent collections, retrospectives and  visiting exhibitions. Along these lines, someone asked whether it’s better to try to change men’s mindsets and have them seek change or is it better to have women pressure institutions to make the desired changes.

visiting exhibitions. Along these lines, someone asked whether it’s better to try to change men’s mindsets and have them seek change or is it better to have women pressure institutions to make the desired changes.

“It’s a really good military strategy to attack your enemy from all sides,” Kahlo answered. “The challenge now is to get more male feminists. There are too men who just can’t imagine voting for a smart, strong well-qualified woman and that’s the deep dark secret of the Democratic Party.

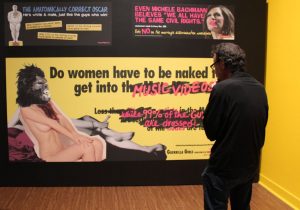

The question is not why aren’t there more great women painters.

“The appropriate question is why don’t we regard more women painters as great? And why have they been locked out of the institutions that allow them to train and exhibit. They’re not showing the history of art, they’re showing the history of wealth and power – of the limited number of men who’ve won a popularity contest among art dealers and billionaire collectors and museum curators.”

“The appropriate question is why don’t we regard more women painters as great? And why have they been locked out of the institutions that allow them to train and exhibit. They’re not showing the history of art, they’re showing the history of wealth and power – of the limited number of men who’ve won a popularity contest among art dealers and billionaire collectors and museum curators.”

“Are there any male Guerrilla Girls,” another audience member asked.

“Do you know how hard it is to get a guy to work for no credit and no money?” teased Kahlo. “We’re not dogmatic about that but we just haven’t found any guys, although we’re  always looking,” she added, turning serious for a moment.

always looking,” she added, turning serious for a moment.

“What advice do you have for young and old cage rattlers?”

“Just keep rattling cages. What we found is that if you think of a way to do something that’s unforgettable, people won’t forget it. We’ve always wanted to transform people. You should try to think like the people  who are trying to keep you in a cage.”

who are trying to keep you in a cage.”

Three ancillary questions further illustrated Kahlo’s wry take on the state of the arts and the Guerrilla Girls posture as a fulcrum of change.

Who is your favorite painter, an audience member wanted to know.

“I’m only one of the many artists of the collective and each of us  has our personal favorite but our group is not about promoting any individual artist. We actually support all artists. We think that the world needs more artists.”

has our personal favorite but our group is not about promoting any individual artist. We actually support all artists. We think that the world needs more artists.”

What do you think of the Trump Administration’s denigration of the arts?

“They’ve denigrated everything and I’m kind of happy that art and culture is at the bottom of their list of things they think are important. I’m amazed at how racist and sexist and homophobic and how corrupt the Trump  Administration is. I see it as a goal that all fairminded people have to try to reverse that.

Administration is. I see it as a goal that all fairminded people have to try to reverse that.

“What do you think of the Andy Warhol show at the Whitney?” asked a New Yorker who’d flown down just to attend the opening.

“I haven’t seen it because I’ve really seen enough of Andy Warhol. I’m from Pittsburgh and I’ve even been to his grave.”

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.