Beacons

![]() Beacons consists of three 10-foot-high by 4-foot-wide brushed aluminum kinetic sculptures created by metal sculptor Harry McDaniel. Enabled by stainless steel ball bearings, the tops have “branches that spin in the wind.” According to the artist, the tapering upright forms of each piece are suggestive of the lighthouses that can be seen in various places along the west coast of Florida. As the top sections move in the wind, they reflect light in all directions as do the “beacons” of a lighthouse.

Beacons consists of three 10-foot-high by 4-foot-wide brushed aluminum kinetic sculptures created by metal sculptor Harry McDaniel. Enabled by stainless steel ball bearings, the tops have “branches that spin in the wind.” According to the artist, the tapering upright forms of each piece are suggestive of the lighthouses that can be seen in various places along the west coast of Florida. As the top sections move in the wind, they reflect light in all directions as do the “beacons” of a lighthouse.

![]() The grouping is located in a landscaped area near the drop-off entry circle/overhang area of Sugden Hall that is similar to a drop-off area that is found at a resort.

The grouping is located in a landscaped area near the drop-off entry circle/overhang area of Sugden Hall that is similar to a drop-off area that is found at a resort.

Beacons is part of the Florida Art in Public Buildings program, an initiative started in 1979 pursuant to section 255.043 of the Florida Statutes, which earmarks 0ne-half of one percent of the amount the legislature appropriates for the construction of state buildings for the acquisition of public artworks. It was installed in 2012 at a cost of $20,650.

The Three Beacons

The Sanibel Island Lighthouse

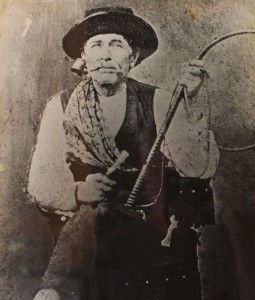

According to authors Yvonne Hill and Marguerite Jordan (Images of America, Sanibel Island), the Sanibel Lighthouse “was a beacon of hope” for the island’s residents and visitors alike. The lighthouse became a necessity in the last quarter of the 19th Century, as local cattlemen such as Cracker King Jake Summerlin (right), Capt. F.A. Hendry and William H. Towles shipped increasing numbers of beef

According to authors Yvonne Hill and Marguerite Jordan (Images of America, Sanibel Island), the Sanibel Lighthouse “was a beacon of hope” for the island’s residents and visitors alike. The lighthouse became a necessity in the last quarter of the 19th Century, as local cattlemen such as Cracker King Jake Summerlin (right), Capt. F.A. Hendry and William H. Towles shipped increasing numbers of beef  stock to Havana from the deep water wharf and cow pens built by Union soldiers in Punta Rassa during the Civil War. Today, the 120-year-old lighthouse is a picturesque point of interest where tourists gather to take photographs, especially in the early morning and late evening against the backdrop of the rising and setting sun. But sitting in a wildlife preserve, the lighthouse and its 127 steps are closed to the public.

stock to Havana from the deep water wharf and cow pens built by Union soldiers in Punta Rassa during the Civil War. Today, the 120-year-old lighthouse is a picturesque point of interest where tourists gather to take photographs, especially in the early morning and late evening against the backdrop of the rising and setting sun. But sitting in a wildlife preserve, the lighthouse and its 127 steps are closed to the public.

The island’s early settlers and fishermen had actually petitioned Congress back in 1833 to place a lighthouse on the island, but their entreaties went unheeded. According to the historical marker at the lighthouse, in the late 1870s, the U.S. Lighthouse Board took the initiative in requesting funds for a lighthouse on Sanibel Island, stating in its application that:

“A light on Sanabel [sic] Island would supply a want that has long been felt for a light-house between Key West and Egmont Key. The coastwise trade of Florida is considerable, and increasing. A great number of sailing-vessels, also six steamers, are now plying between Key West and ports on the west coast of Florida; and vessels bound across Florida Bay make their landfall at and take their departure from the southern point of Sanabel [sic] Island.”

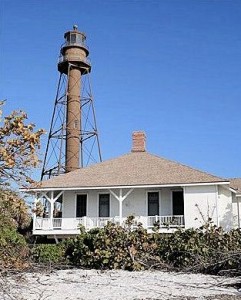

It was not until 1883, however, that Congress finally appropriated the $50,000 needed for the project. While the superstructure was being fabricated in a metal factory in New Jersey, work began on the eastern tip of the island in February 1884 that included a 162-foot-long wharf built on creosoted piles to facilitate the unloading of building supplies for the tower and for two square keeper’s dwellings, topped by hipped roofs and supported by iron pilings. Just two miles from Sanibel Island, the ship carrying the superstructure ran aground on a shoal and sank. Assisted by a diver, crews aboard the lighthouse tenders Arbutus and Mignonette were able to recover almost all of the pieces.

It was not until 1883, however, that Congress finally appropriated the $50,000 needed for the project. While the superstructure was being fabricated in a metal factory in New Jersey, work began on the eastern tip of the island in February 1884 that included a 162-foot-long wharf built on creosoted piles to facilitate the unloading of building supplies for the tower and for two square keeper’s dwellings, topped by hipped roofs and supported by iron pilings. Just two miles from Sanibel Island, the ship carrying the superstructure ran aground on a shoal and sank. Assisted by a diver, crews aboard the lighthouse tenders Arbutus and Mignonette were able to recover almost all of the pieces.

The 104-foot-tall structure consists of four iron legs arranged in a pyramidal fashion around a cylindrical central column that stops about 20 feet from the ground and must be accessed by an external staircase. The lighthouse was fitted with a third-order French-built lens designed by the French physicist Augustin Fresnel in 1822. Set at a height of 98 feet, the lens originally emitted a fixed white light that was interrupted in two-minute intervals by a brighter surge in light that could be seen 16 miles out to sea. Fueled by kerosene, the light was lit for the first time on August 20, 1884 by keeper Dudley Richardson.

The 104-foot-tall structure consists of four iron legs arranged in a pyramidal fashion around a cylindrical central column that stops about 20 feet from the ground and must be accessed by an external staircase. The lighthouse was fitted with a third-order French-built lens designed by the French physicist Augustin Fresnel in 1822. Set at a height of 98 feet, the lens originally emitted a fixed white light that was interrupted in two-minute intervals by a brighter surge in light that could be seen 16 miles out to sea. Fueled by kerosene, the light was lit for the first time on August 20, 1884 by keeper Dudley Richardson.

In 1933, the light pattern was changed to two sequential white flashes every ten seconds. In 1962, the lighthouse was converted to electricity. In the process of electrifying the light, the Coast Guard removed the tower’s third-order Fresnel lens and installed a 300 millimeter drum lens that had been used on a lightship. “One year later, an electrical outage caused the lighthouse to go dark for one week, ruining its 79-year perfect record for continuous power,” Hill and Jordan report.

In 1972, the Coast Guard proposed discontinuing the lighthouse, but feedback provided by local residents and mariners convinced them to keep it lit. The City of Sanibel assumed management of the lighthouse property in 1982. The tower itself was officially transferred to the city some 28 years later, during a ceremony held April 21, 2010. Using a $50,000 state historic preservation grant and money from its beach parking fund, Sanibel City Council awarded a $269,563 contract to Razorback LLC in May 2013 to restore the lighthouse. During the summer of 2013, the contractors replaced sections of deteriorated steel on the tower and then sanded and painted the exterior.

The lighthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is still an active aid to navigation.

The Boca Grande Pass and Gasparilla Island Lighthouses

In 1888, the U.S. Congress allocated $35,000 for the U.S. Lighthouse Service to build a lighthouse on the southern tip of Gasparilla Island to mark the entrance to Boca Grande Pass, the deepest natural port in the state. By the time the lighthouse was lit on December 31, 1890, the port at Boca Grande had become the hub for the local phosphate industry, which mined the mineral along the Pearl River, placed it on barges, which were unloaded onto ships in Boca Grande Pass for transport to other destinations for processing.

In 1888, the U.S. Congress allocated $35,000 for the U.S. Lighthouse Service to build a lighthouse on the southern tip of Gasparilla Island to mark the entrance to Boca Grande Pass, the deepest natural port in the state. By the time the lighthouse was lit on December 31, 1890, the port at Boca Grande had become the hub for the local phosphate industry, which mined the mineral along the Pearl River, placed it on barges, which were unloaded onto ships in Boca Grande Pass for transport to other destinations for processing.

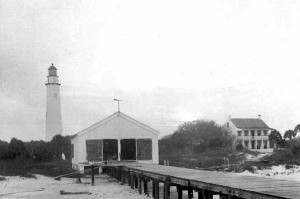

The wooden lighthouse was constructed atop a series of iron pilings that elevated the structure, protecting it from frequent high water caused storms and hurricanes of the gulf. On top and in the center of the one-story dwelling, a square tower was constructed, which supported a circular lantern room inside an octagonal cupola that raised the elevation of the light to 44 feet. The light was an iron screw pile design with wood frame that

The wooden lighthouse was constructed atop a series of iron pilings that elevated the structure, protecting it from frequent high water caused storms and hurricanes of the gulf. On top and in the center of the one-story dwelling, a square tower was constructed, which supported a circular lantern room inside an octagonal cupola that raised the elevation of the light to 44 feet. The light was an iron screw pile design with wood frame that  originally utilized a 3 ½ order clam-shaped Fresnel lens that was used to broadcast a white light interrupted by flashes of red out to sea. The lens opened and closed as it rotated. Today, a 5th order drum lens has taken the place of the original lens.

originally utilized a 3 ½ order clam-shaped Fresnel lens that was used to broadcast a white light interrupted by flashes of red out to sea. The lens opened and closed as it rotated. Today, a 5th order drum lens has taken the place of the original lens.

Adjacent to the lighthouse, another almost identical building was constructed, minus the tower and lantern. It was used as an assistant keepers dwelling.

Adjacent to the lighthouse, another almost identical building was constructed, minus the tower and lantern. It was used as an assistant keepers dwelling.

In 1932, the Gasparilla Island Rear Range Light came into operation on Gasparilla Island. Built in 1885 as the Delaware Breakwater Rear Range  Light, it was dismantled in 1921 and shipped to Miami. In 1927 it was shipped to Gasparilla Island and reassembled. It was relit in 1932, and had a companion light, the Front Range Light, in the Gulf of Mexico off of Gasparilla Island. When the two lights lined up, a ship’s navigator knew it was time to turn to enter Boca Grande Pass.

Light, it was dismantled in 1921 and shipped to Miami. In 1927 it was shipped to Gasparilla Island and reassembled. It was relit in 1932, and had a companion light, the Front Range Light, in the Gulf of Mexico off of Gasparilla Island. When the two lights lined up, a ship’s navigator knew it was time to turn to enter Boca Grande Pass.

In 1939, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) took over operation of lighthouses from the U.S. Lighthouse Service. During World War II,  the lighthouse was used to watch for German U-boats and a submarine watch tower was erected to the west of the light to facilitate that effort. The keeper, Cody McKeithan, kept in touch with the Coast Guard by radio. The radio was kept on the second floor of the lighthouse.

the lighthouse was used to watch for German U-boats and a submarine watch tower was erected to the west of the light to facilitate that effort. The keeper, Cody McKeithan, kept in touch with the Coast Guard by radio. The radio was kept on the second floor of the lighthouse.

The port was used as a safe harbor at night, with up to 30 ships mooring at the dock to avoid German subs. While it was not reported at the time, the Merchant Marine reports that as many as 189 merchant and military ships were sunk by subs in the Gulf of Mexico and the Carribean in 1942 alone.

In 1956 the light was automated, and the era of lighthouse keepers on Gasparilla Island came to an end. The light was deactivated in 1966 and a year later the Coast Guard abandoned the facility, leaving the station to the elements and vandalism until ownership transferred from the federal government to the care of the local county government. By this time, erosion had chewed away at the shoreline along the southern tip of the island which left the screw piles exposed. The light began to tilt, and soon the entire structure was in danger of falling into the Pass.

In 1956 the light was automated, and the era of lighthouse keepers on Gasparilla Island came to an end. The light was deactivated in 1966 and a year later the Coast Guard abandoned the facility, leaving the station to the elements and vandalism until ownership transferred from the federal government to the care of the local county government. By this time, erosion had chewed away at the shoreline along the southern tip of the island which left the screw piles exposed. The light began to tilt, and soon the entire structure was in danger of falling into the Pass.

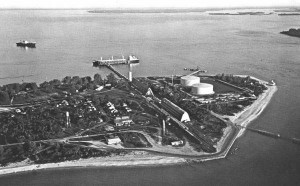

Local residents petitioned the federal government to assist in rebuilding the shoreline, but their appeals were ignored. But in 1972 the light and the land around it were transferred to Lee County. In 1980, the Gasparilla Island Conservation and Improvement Association was successful in getting the structure placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and set about raising funds for the restoration of the

Local residents petitioned the federal government to assist in rebuilding the shoreline, but their appeals were ignored. But in 1972 the light and the land around it were transferred to Lee County. In 1980, the Gasparilla Island Conservation and Improvement Association was successful in getting the structure placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and set about raising funds for the restoration of the  property. When FPL had to dredge the basin of the oil dock next to the lighthouse in 1982, they placed the sand around the light, shoring it up. FPL also had two rock groins built in front of the light to help retain the sand. The buildings were fully restored in 1985-1986, including the installations of a 377 mm drum lens, putting the old lighthouse back into service as an active aid to navigation.

property. When FPL had to dredge the basin of the oil dock next to the lighthouse in 1982, they placed the sand around the light, shoring it up. FPL also had two rock groins built in front of the light to help retain the sand. The buildings were fully restored in 1985-1986, including the installations of a 377 mm drum lens, putting the old lighthouse back into service as an active aid to navigation.

In 1988 the lighthouse and the land around it was transferred to the State of Florida. Housing a museum that is dedicated to sharing the history of the lighthouse and local area, the lighthouse today serves as the centerpiece of Gasparilla Island State Park. It is one of only six lighthouses in Florida that is open to the public, and the only one on the west coast. Barrier Island Parks Society, a nonprofit Citizen Support Organization, manages and operates the museum.

In 2007, the lighthouse won the “Best Looking Lighthouse” award from Florida Monthly Magazine.

The Egmont Key Lighthouse in Tampa Bay

It has long been believed that Hernando Desoto first discovered the small island located at the mouth of the Tampa Bay before his famous expedition exploring the American interior. However the island owes its name British surveyor George Gauld, who named the small island after John Perceval, second Earl of Egmont and First Lord of the Admiralty. Through the years, the island has been home to two lighthouses, a fort, a movie theater, a cemetery, boat pilots, and a radio beacon. Today, all that remains on the island is a truncated lighthouse, crumbling remains of the fort, a small colony of gopher tortoises, and a park ranger to interpret the island’s history.

It has long been believed that Hernando Desoto first discovered the small island located at the mouth of the Tampa Bay before his famous expedition exploring the American interior. However the island owes its name British surveyor George Gauld, who named the small island after John Perceval, second Earl of Egmont and First Lord of the Admiralty. Through the years, the island has been home to two lighthouses, a fort, a movie theater, a cemetery, boat pilots, and a radio beacon. Today, all that remains on the island is a truncated lighthouse, crumbling remains of the fort, a small colony of gopher tortoises, and a park ranger to interpret the island’s history.

The effort to erect a lighthouse on Egmont Key began on July 5, 1837, when Lieutenant Napoleon L. Coste filed the following report at the behest of Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury on the need for a lighthouse at the entry to Tampa Bay:

“

I have the honor to report that the first place which presents itself to me of importance for the erection of a light-house, is at the mouth of Tampa bay, on the north point of Eggmont [sic] key. The western coast of Florida is very low, and similar in appearance, making it necessary for the mariner to have some mark by which he could take his departure; and as Eggmont [sic] is the point which all vessels endeavor to make when bound to St. Mark’s, Appalachicola, or St. Joseph’s, it is my opinion, that by the erection of a light-house on the point above mentioned, the navigation of the coast would be facilitated, and much property saved which is now annually lost by shipwreck. It is also important that I should inform you that a light-house would be a leading mark over the bar into Tampa bay, a bar capable of admitting small class frigates, and navigable to within ten miles of its head for sloops-of-war at all times.”

At the time, the federal government was embroiled in a war with the Seminole Indians that lasted until the Spring of 1842. With costs associated with the war exceeding $40 million, Congress was ill prepared to appropriate any money for a lighthouse. But after Florida achieved statehood in 1845, shipping traffic in and out of Tampa Bay increased dramatically and two years later, Congress finally approved $10,000 for a lighthouse on Egmont Key.

At the time, the federal government was embroiled in a war with the Seminole Indians that lasted until the Spring of 1842. With costs associated with the war exceeding $40 million, Congress was ill prepared to appropriate any money for a lighthouse. But after Florida achieved statehood in 1845, shipping traffic in and out of Tampa Bay increased dramatically and two years later, Congress finally approved $10,000 for a lighthouse on Egmont Key.

Work began on the lighthouse during the summer of 1847. The project was on schedule to be completed by January 1, 1848 when the supply ship Abbe Baker, which was transporting bricks from New York for the lighthouse, ran aground on Orange Key. Nearly half of the bricks in the ship’s manifest had to be tossed overboard in order to refloat the ship. By February of 1848, the tower stood at a height of twenty feet, but work had to be halted until a new shipment of bricks arrived. The tower was officially certified on April 19, 1848, with Sherrod Edwards, the first keeper of Egmont Key Lighthouse, activating the light for the first time a short while later. At that time, the lighthouse was the only one between Key West and St. Marks.

Work began on the lighthouse during the summer of 1847. The project was on schedule to be completed by January 1, 1848 when the supply ship Abbe Baker, which was transporting bricks from New York for the lighthouse, ran aground on Orange Key. Nearly half of the bricks in the ship’s manifest had to be tossed overboard in order to refloat the ship. By February of 1848, the tower stood at a height of twenty feet, but work had to be halted until a new shipment of bricks arrived. The tower was officially certified on April 19, 1848, with Sherrod Edwards, the first keeper of Egmont Key Lighthouse, activating the light for the first time a short while later. At that time, the lighthouse was the only one between Key West and St. Marks.

In the 1850s, the U.S. Government instigated another war with the Seminoles that was designed to round up and deport the 600 or so Indians still living in the Everglades south of the Peace River and west of Lake Okeechobee. A stockade was built on Egmont Key to hold Seminole Indians captured by federal troops and three companies of Florida volunteers, who ventured deep into the Glades in long, flat-bottomed steel boats large enough to hold 16 men with all their supplies. Only 41 Indians were brought to Egmont during the war and they were picked up on May 5, 1858 by the steamer Grey Cloud, which was bound for New Orleans and then Oklahoma with Chief Billy Bowlegs and 124 of his tribesmen, women and children, who’d surrendered to the soldiers at Fort Myers in March of that year.

In the 1850s, the U.S. Government instigated another war with the Seminoles that was designed to round up and deport the 600 or so Indians still living in the Everglades south of the Peace River and west of Lake Okeechobee. A stockade was built on Egmont Key to hold Seminole Indians captured by federal troops and three companies of Florida volunteers, who ventured deep into the Glades in long, flat-bottomed steel boats large enough to hold 16 men with all their supplies. Only 41 Indians were brought to Egmont during the war and they were picked up on May 5, 1858 by the steamer Grey Cloud, which was bound for New Orleans and then Oklahoma with Chief Billy Bowlegs and 124 of his tribesmen, women and children, who’d surrendered to the soldiers at Fort Myers in March of that year.

It was during this time that the lighthouse was torn down due to damage it sustained during several strong hurricanes and a lightning strike that opened cracks in the tower. Following a $16,000 appropriation made by Congress on August 18, 1856, a new tower was completed in 1857 roughly ninety feet inland from the site of the previous tower. At 87 feet, it was twice as tall as the original tower, and with three-foot-thick walls, it was better able to withstand the winds and storm surge associated with gulfcoast storms.

Starting in 1858, the lighthouse exhibited a fixed-light produced by a third-order Fresnel lens at a focal plane of 86 feet.

With the advent of the Civil War and installation of the Anaconda Plan’s Union blockade of the coast from Maryland around the Florida peninsula and up the Mississippi, Egmont Key Lighthouse Keeper George V. Rickard knew it was only a matter of months before the Union seized control of the lighthouse for the North. Rickard feigned allegiance to Union blockaders stationed under the command of Lt. Comdr. William B. Eaton near the island, but while the Union gunboats were on patrol one day, Rickard crated up the Fresnel lens and hightailed it to Tampa with as many supplies as he could transport. It was only a delaying tactic. Union naval forces seized the lighthouse and installed a makeshift light, and it was not until after June 2, 1866 that a fourth-order lens was placed in the tower and used until 1896, when it was replaced by a third-order lens with two red sectors.

“In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, Fort Dade was constructed on the island as part of a comprehensive coastal defense system,.” states Lighthousefriends.com. The fort, along with another on Mullet Island to the northeast, stood watch over the entrance to Tampa Bay.

A 1907 Light List noted that a conch shell would be sounded at Egmont Key in answer to signals from passing vessels. This unique fog signal was replaced on February 18, 1916 by a bell struck by machinery.

“The fort was staffed during World War I as well,” Lighthousefriends.com continues, “and by the time it was deactivated in 1923, a movie theater, bowling alley, tennis courts, and miles of brick roads had been constructed on the island. In 1915, an acetylene light was established atop a reinforced concrete pile structure to form, with Egmont Key Lighthouse, a set of range lights. A radio beacon was added to the station in 1930.”

In 1944, the upper portion of the lighthouse was removed along with the Fresnel lens, and a double-headed DCB-36 Rotating Beacon was placed on top of the capped tower.

The remaining keeper’s dwelling was demolished in 1954 and replaced by a one-story barracks. In 1974, Egmont Key became a National Wildlife Refuge, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The island was also added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, due to the lighthouse and remains of Fort Dade. With the addition of a DCB-24 Rotating Beacon in 1990, the lighthouse became the last lighthouse in the country to be automated. The Egmont Key Lighthouse was also the last remaining staffed lighthouse in Florida and one of only seven in the United States. Today, the Florida Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service work together to manage the island.

The lighthouse celebrated its 150th anniversary in November of 2008. In 2013, the lens pedestal from Egmont Key Lighthouse was shipped to Tallahassee to be restored by the Florida State Conservation Laboratory. Volunteers working at the lighthouse hope this is just one small step towards restoring the lighthouse to its pre-1944 appearance.

Egmont Key is open to the public and there are a number of organizations that run tours out to the island. Along with the lighthouse, the island offers unaltered beaches and an old fort just waiting to be explored. While the lighthouse itself is not open to the public, visitors may walk the grounds and enjoy the views of the lighthouse

About Kinetic Monumental Sculptor Harry McDaniel

![]() Harry McDaniel is a nationally-recognized Asheville, North Carolina monumental sculptor whose work typically includes some form of kinetic aspect. “Most of those pieces have been outdoor sculptures in aluminum, but I have also created some mobiles and I have worked with other materials. The kinetic aspect of my mobiles has evolved into outdoor kinetic sculptures,” McDaniel stated.

Harry McDaniel is a nationally-recognized Asheville, North Carolina monumental sculptor whose work typically includes some form of kinetic aspect. “Most of those pieces have been outdoor sculptures in aluminum, but I have also created some mobiles and I have worked with other materials. The kinetic aspect of my mobiles has evolved into outdoor kinetic sculptures,” McDaniel stated.

![]() Through the years, McDaniel’s artwork has demarked by a diversity of materials, style, technique, and content. “It is difficult to explain the diversity, except to say that I love to experiment and I am drawn to new challenges,” the sculptor admits.” I have worked with wood, metals, cement, plastic, and found objects. Some of the threads that tie my work together are humor, a fascination with curves, motion (or implied motion), and an interest in the human condition. My sculptures can roughly be divided into two parts–decorative works and social commentary.

Through the years, McDaniel’s artwork has demarked by a diversity of materials, style, technique, and content. “It is difficult to explain the diversity, except to say that I love to experiment and I am drawn to new challenges,” the sculptor admits.” I have worked with wood, metals, cement, plastic, and found objects. Some of the threads that tie my work together are humor, a fascination with curves, motion (or implied motion), and an interest in the human condition. My sculptures can roughly be divided into two parts–decorative works and social commentary.

Decorative Works and Public Art

![]() McDaniel’s decorative works include freestanding sculptures (indoor and outdoor), wall pieces, and mobiles. They range in size from tabletop pieces to a 200′ long outdoor sculpture (Ghost Train). These works tend to be curvy, abstract, distorted geometric forms. Most embody a strong sense of motion. “I am intrigued by motion or, more accurately, the paths taken by objects in motion,” McDaniel expounds.” I love to let my eyes trace the path of a bird swooping through the air or a fish gliding through water. Many of my sculptures are like 3-D snapshots of such motions.

McDaniel’s decorative works include freestanding sculptures (indoor and outdoor), wall pieces, and mobiles. They range in size from tabletop pieces to a 200′ long outdoor sculpture (Ghost Train). These works tend to be curvy, abstract, distorted geometric forms. Most embody a strong sense of motion. “I am intrigued by motion or, more accurately, the paths taken by objects in motion,” McDaniel expounds.” I love to let my eyes trace the path of a bird swooping through the air or a fish gliding through water. Many of my sculptures are like 3-D snapshots of such motions.

Mobiles and Kinetic Scuptures

![]() While most of McDaniel’s decorative pieces contain aspects of implied motion, the mobiles and kinetic sculptures are literally set in motion by ball-bearing assisted wind power. “The delicate balance and subtle, graceful, gliding motions of mobiles have intrigued me since I was a child,” Harry explains. “As a sculptor I appreciate the ever-changing shapes and intersections of lines and the sense of life conveyed by the sculpture’s response to air movement. My largest mobile is a 55′ long installation called Eclipse that I created for a hospital lobby.”

While most of McDaniel’s decorative pieces contain aspects of implied motion, the mobiles and kinetic sculptures are literally set in motion by ball-bearing assisted wind power. “The delicate balance and subtle, graceful, gliding motions of mobiles have intrigued me since I was a child,” Harry explains. “As a sculptor I appreciate the ever-changing shapes and intersections of lines and the sense of life conveyed by the sculpture’s response to air movement. My largest mobile is a 55′ long installation called Eclipse that I created for a hospital lobby.”

Social Commentary

McDaniel also creates works of social commentary that include his American Artifacts series, figurative pieces, and other works. These pieces often include an element of humor. The materials are often related to the meaning of the pieces. Some pieces are based on McDaniel’s personal experiences and struggles; others are derived from his observations and understandings of the world around him.

American Artifacts

The American Artifacts series is a group of mixed-media sculptures accompanied by text. The work is created and presented in a form that simulates an exhibit in a natural history museum. At first glance, the sculptures appear to be artifacts from some foreign or primitive culture, but on closer inspection viewers find that the “artifacts” are derived from objects common to modern life in the United States. The accompanying text describes the objects in a style reminiscent of the descriptions one might find in a natural history museum beside stone axes and broken ceramic figurines, yet it refers to our own culture.

Figurative Works

“A significant amount of my artwork has included the human figure in one form or another,” McDaniel observes.” My work has included life-size figures, portions of figures, and installations using mannequins. I find something particularly compelling in life-size human figures. They tend to create a strong presence in a room regardless of the style or material. We are ‘programmed’ (psychologically if not biologically) to relate to the human form in certain ways. When a viewer encounters a figurative sculpture he brings a certain familiarity that, at least for a moment, allows him to feel a likeness to the sculpture. The viewer also feels his difference of course, and from this contradiction he must draw some meaning.”

The entire range of McDaniel’s sculptures (more than 100 images) can be seen on his website: <HarryMcDaniel.com>.

Biographical Information

Harry McDaniel was born in 1959 in Wichita, Kansas. As a child, he lived in Missouri, New Jersey, and North Carolina. He recalls that growing up he always enjoyed taking things apart and putting them back together. “My mother tells me that I took my pacifiers apart.” He did some drawing and painting as a boy, but was more interested in building go-carts and tree forts. As a young adult, he was drawn to art, but did not anticipate that he would make a career as a sculptor. “In 1983, I took a painting class at a community art center in Connecticut and really liked it,” says McDaniel of the turning point in his career.” I then took a metal sculpture class and really liked it too. In the summer of 1984 I saw an ad in a local weekly paper requesting design submissions for a public art project for the train station in Stamford, Connecticut. I had looked at public sculptures many times and thought ‘I could do better than that,’ so I decided it was time to put my money where my mouth was.” He spent the next week designing and creating a couple of models. “I became totally absorbed in the project and at the end of the week (though I was not awarded the commission) it was clear that creating artwork was deeply satisfying to me and I needed to make it an ongoing part of my life.”

Public Art Projects

In the past 25 years, he has produced a wide range of sculptures, including the following public art installations:

- 2013 Flourish; Rockville Senior Center; Rockville, MD

- 2012 Beacons; Florida Gulf Coast University; Fort Myers, FL

- 2011 Cormorant; Valdosta State University; Valdosta, GA

- 2011 A Flower for Giving; Lenoir Memorial Hospital; Kinston, NC

- 2010 Ghillie Dhu’s Enchantment; City Center Park; Gastonia, NC

- 2008 Deco Gecko; Pritchard Park; Asheville, NC

- 2007 Redbird; Fred Fletcher Park; Raleigh, NC

- 2004 Dancers; Florida State University;Tallahassee, FL

- 2004 Spires (purchase); Florida Atlantic University; Boca Raton, FL

- 2003 Fiddleheads; UNCA-Kellogg Center; Hendersonville, NC

- 2003 Ghost Train; New River Trail State Park; Pulaski, VA

- 2001 Avian Muse; 30′ long mobile; Robert Morgade Library; Stuart, FL

- 2000 Neptunian Frolic (purchase); Brevard County Health Dept.; Titusville, FL

- 1999 Eclipse; Outpatient lobby, Moore Regional Hospital; Pinehurst, NC

- 1988 Agrisculpture; suspended sculpture; Agricultural History Park; Derwood, MD

For exhibition history and additional biographical information, please refer to: <HarryMcDaniel.com>

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.