App’s use and purpose

You see them all around as you stroll the River District. Some are abstract. Others are representational. They all tell stories about Fort Myers’ early history. They’re the City’s public artworks, but even people who encounter them on a daily basis cannot tell you who made them, how were they fabricated or what they’re about! Well, that’s about to change thanks to a new mobile app platform

You see them all around as you stroll the River District. Some are abstract. Others are representational. They all tell stories about Fort Myers’ early history. They’re the City’s public artworks, but even people who encounter them on a daily basis cannot tell you who made them, how were they fabricated or what they’re about! Well, that’s about to change thanks to a new mobile app platform  by the name of Otocast.

by the name of Otocast.

“We determined last year that Otocast is an ideal mechanism for enabling the City to showcase its public art collection,” notes River District Alliance Director Jared Beck (right), who served as Chairman when the City’s Public Art Committee contracted for the service in 2017.

The app is free and available for download in the iTunes store  and on Google Play.

and on Google Play.

Otocast works through geo-location mapping. Users don’t need to know anything about an artwork they happen upon. There’s no need to look for a plaque or QR Code. You don’t need to know the name of the artist or the title of the piece. Simply tap on the app and the guide automatically comes up, providing access to an array of information about the art piece you’re looking at. The app will also identify other public artworks located nearby.

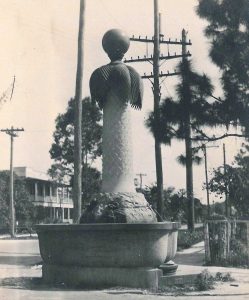

The City of Fort Myers has been quietly building a prestigious public art collection for decades. Its earliest public artwork, the Tootie McGregor Fountain, dates back to 1913. Uncommon Friends author James D. Newton gifted The Spirit of Fort Myers (popularly known as Rachel at the Well) to the City in 1926, and 33 years later, local resident Evelyn Rea willed an 1880 white marble sculpture of a German siren named Lorelei to the local library. But it would be another 30 years before the City’s Beautification Advisory Board began commissioning a North Fort Myers sculptor by the name of D.J. Wilkins (seventh photo) to cast more than 20

The City of Fort Myers has been quietly building a prestigious public art collection for decades. Its earliest public artwork, the Tootie McGregor Fountain, dates back to 1913. Uncommon Friends author James D. Newton gifted The Spirit of Fort Myers (popularly known as Rachel at the Well) to the City in 1926, and 33 years later, local resident Evelyn Rea willed an 1880 white marble sculpture of a German siren named Lorelei to the local library. But it would be another 30 years before the City’s Beautification Advisory Board began commissioning a North Fort Myers sculptor by the name of D.J. Wilkins (seventh photo) to cast more than 20  representational sculptures which included such Centennial Park artistic landmarks as The Florida Panther (1988), Uncommon Friends (1988), The Great Turtle Chase (2000) and USCT 2nd Regiment Memorial (2000).

representational sculptures which included such Centennial Park artistic landmarks as The Florida Panther (1988), Uncommon Friends (1988), The Great Turtle Chase (2000) and USCT 2nd Regiment Memorial (2000).

In 2001, Florida Power & Light Co. gave the city Caloosahatchee Manuscripts (the Jim Sanborn light sculpture that bathes the Sidney & Berne Davis  Art Center in illuminated letters after nightfall) to commemorate the conversion of its power plant from oil to natural gas. But it was not until 2004 that the city established a formal public art program, which has added such modernist works as Fire Dance in Centennial Park, the branding iron totem (Stacked Brands) in the courtyard of the new library and the silhouettes in Clemente Park (What Dreams May Fly and How They Fly), among others.

Art Center in illuminated letters after nightfall) to commemorate the conversion of its power plant from oil to natural gas. But it was not until 2004 that the city established a formal public art program, which has added such modernist works as Fire Dance in Centennial Park, the branding iron totem (Stacked Brands) in the courtyard of the new library and the silhouettes in Clemente Park (What Dreams May Fly and How They Fly), among others.

According to urban planners, economists and public art professionals, people who live and work in communities with a vibrant public art program enjoy more than three dozen interrelated benefits from the art that surrounds them. But these salutatory effects are only fully realized to the extent people are able to interact with the artworks on a physical, intellectual and emotional level. Otocast facilitates a deeper connection with public art by letting viewers in on behind-the-scenes

According to urban planners, economists and public art professionals, people who live and work in communities with a vibrant public art program enjoy more than three dozen interrelated benefits from the art that surrounds them. But these salutatory effects are only fully realized to the extent people are able to interact with the artworks on a physical, intellectual and emotional level. Otocast facilitates a deeper connection with public art by letting viewers in on behind-the-scenes  stories previously known only to the art insiders who commissioned, made and installed the sculptures, murals and other artworks that dot the urban landscape.

stories previously known only to the art insiders who commissioned, made and installed the sculptures, murals and other artworks that dot the urban landscape.

To fill this void, Otocast includes written narrative describing each artwork along with historical photographs that depict what the artwork looked like when it was originally installed. But the app’s centerpiece  is an audio recording made by the artist who created the piece or someone who is intimately familiar with the artwork or the stories it symbolizes.

is an audio recording made by the artist who created the piece or someone who is intimately familiar with the artwork or the stories it symbolizes.

By virtue of this audio component, Otocast is like having your very own tour guide who knows all the cool facts  and inside stories about the things you want to see. In fact, in other towns and cities where Otocast is already in use (there’s presently more than 150 guides encompassing in excess of 3,000 individual artworks , and the number’s growing all the time), the app serves as a platform for self-guided audio tours that encourage exploration and discovery, helping people gain a better appreciation of their cultural legacy. This feature is particularly useful in a town like Fort Myers, where many of the pieces in the city’s public art collection tell tales about the pioneers who built a rough-and-tumble cow town out of the remnants of an old wooden frontier outpost in the years following the end of the Civil War.

and inside stories about the things you want to see. In fact, in other towns and cities where Otocast is already in use (there’s presently more than 150 guides encompassing in excess of 3,000 individual artworks , and the number’s growing all the time), the app serves as a platform for self-guided audio tours that encourage exploration and discovery, helping people gain a better appreciation of their cultural legacy. This feature is particularly useful in a town like Fort Myers, where many of the pieces in the city’s public art collection tell tales about the pioneers who built a rough-and-tumble cow town out of the remnants of an old wooden frontier outpost in the years following the end of the Civil War.

“Otocast accommodates people who just want to know more about a particular  landmark as well as individuals and small groups who desire to spend an hour or two touring all the artworks in a given location at their own pace,” observes Otocast Founder and CEO Eric Feinstein. “Some of our users have even developed puzzles and scavenger hunts to encourage people to learn more about their landmarks and early history.”

landmark as well as individuals and small groups who desire to spend an hour or two touring all the artworks in a given location at their own pace,” observes Otocast Founder and CEO Eric Feinstein. “Some of our users have even developed puzzles and scavenger hunts to encourage people to learn more about their landmarks and early history.”

For example, the Boston Harbor Association engaged some puzzle makers to develop a Da Vinci Code-style scavenger hunt that took participants across Boston’s waterfront in a mentally-engaging, family-friendly adventure. At each stop, Otocast provided historical background and location-specific information that ultimately yielded one or two of  the 12 words that solved the puzzle. Participants who provided the correct solution were entered into a random drawing for a $1,000 cash prize.

the 12 words that solved the puzzle. Participants who provided the correct solution were entered into a random drawing for a $1,000 cash prize.

“Because you can’t answer them without being on site for reference, our word puzzles and scavenger  hunts encourage people to interact with places they might not otherwise visit,” Feinstein amplifies.

hunts encourage people to interact with places they might not otherwise visit,” Feinstein amplifies.

The app is versatile enough to eventually include historic and heritage destinations such as the 100-year-old buildings that populate the River District. In fact, many cities and towns throughout the country utilize Otocast not only for public artworks, but for historic sites, architectural landmarks, monuments, nature trails and other points of interest.

The City’s Public Art Committee plans to include some 20 artworks on Otocast.

At present, it has uploaded text and photos for 13 of them.

At present, it has uploaded text and photos for 13 of them.

“The Committee is exercising great care and  deliberation to ensure that the text and images it is including on Otocast are not only fun and interesting, but completely factual and accurate,” notes current Committee Chair Betty Adams. It is also now working with artists to produce audio narration for the works they created. The Committee is tapping noted historians, authors, art professionals and public officials for works created by

deliberation to ensure that the text and images it is including on Otocast are not only fun and interesting, but completely factual and accurate,” notes current Committee Chair Betty Adams. It is also now working with artists to produce audio narration for the works they created. The Committee is tapping noted historians, authors, art professionals and public officials for works created by  artists who are no longer alive. This week alone, recordings have been completed by Albert Paley for the modernist sculpture in the entrance to the Riviera-St. Tropez condominium complex (Naiad), Barbara Jo Revelle for her mural in the federal courthouse/Hotel Indigo courtyard (Fort Myers: An Alternative History), Cheryl Foster for her mosaic sculpture in Clemente Park (What

artists who are no longer alive. This week alone, recordings have been completed by Albert Paley for the modernist sculpture in the entrance to the Riviera-St. Tropez condominium complex (Naiad), Barbara Jo Revelle for her mural in the federal courthouse/Hotel Indigo courtyard (Fort Myers: An Alternative History), Cheryl Foster for her mosaic sculpture in Clemente Park (What  Dreams May Fly and How They Fly) and historian/author Gerri Reaves for the Grecian maiden at the entrance to Edison Park on McGregor (The Spirit of Fort Myers).

Dreams May Fly and How They Fly) and historian/author Gerri Reaves for the Grecian maiden at the entrance to Edison Park on McGregor (The Spirit of Fort Myers).

Although some of the pieces included in the roll-out are not actually owned by the City, the Committee has opted to include them on Otocast because they are nevertheless part of the city’s unique aesthetic landscape.

“Cultural tourism is a growing segment of our economy, and we want visitors to enjoy themselves when they come to Fort Myers,” Adams adds. “Otocast will provide a free and easy way to enjoy Fort Myers’ artistic attractions. The Committee is confident that everyone who uses Otocast to learn more

“Cultural tourism is a growing segment of our economy, and we want visitors to enjoy themselves when they come to Fort Myers,” Adams adds. “Otocast will provide a free and easy way to enjoy Fort Myers’ artistic attractions. The Committee is confident that everyone who uses Otocast to learn more  about our collection and the history it represents will find the experience fun and rewarding.”

about our collection and the history it represents will find the experience fun and rewarding.”

And because the guides are accessible to anyone with the app no matter where they may live or travel, Otocast is also likely to expose the City’s public art collection to cultural tourists in other parts of the country, as well as in Canada and portions of Europe.  The information they see and hear may induce some of them to plan a trip to Southwest Florida rather than some other tourism destination.

The information they see and hear may induce some of them to plan a trip to Southwest Florida rather than some other tourism destination.

And that’s yet one more example of how the arts mean business in Fort Myers and Lee County.

June 7, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.