Spotlight on Darryl Pottorf’s transfer solvent print of McGregor Boulevard

In 1990, Captiva artist Darryl Pottorf was commissioned to create some works of art for Tootie McGregor’s Gulfshore Grille, a restaurant located at the Fort Myers Country Club under lease by the city. Pottorf immersed himself in the archives of the local library, where he located a dozen historical images featuring iconic landmarks, lush tropical foliage and the city’s most famed resident, Thomas Alva Edison. With the City’s blessing,

In 1990, Captiva artist Darryl Pottorf was commissioned to create some works of art for Tootie McGregor’s Gulfshore Grille, a restaurant located at the Fort Myers Country Club under lease by the city. Pottorf immersed himself in the archives of the local library, where he located a dozen historical images featuring iconic landmarks, lush tropical foliage and the city’s most famed resident, Thomas Alva Edison. With the City’s blessing,  he took the photographs to the the old print shop studio on the 35-acre Captiva estate of his friend and mentor, internationally-renowned artist Robert Rauschenberg. Using a new solvent transfer process being developed by the Rauschenberg studio at that time, Pottorf converted the photos into single edition (1 of 1) prints on Arches paper.

he took the photographs to the the old print shop studio on the 35-acre Captiva estate of his friend and mentor, internationally-renowned artist Robert Rauschenberg. Using a new solvent transfer process being developed by the Rauschenberg studio at that time, Pottorf converted the photos into single edition (1 of 1) prints on Arches paper.

The 12 framed works adorned the popular restaurant’s walls until its closing a number of years later. While a few were moved to various city offices, most of the prints were placed in the club’s storage area where, sadly, they began to deteriorate. Recognizing the importance of these works and the growing worldwide reputation of their maker,  the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee voted in 2008 to have the stored prints conserved. In September of 2010, the restored works were hung on anti-theft security hooks in the lobby of the Oscar M. Corbin Jr. City Hall, where they are now on permanent display as part of the City of Fort Myers public art collection.

the City of Fort Myers Public Art Committee voted in 2008 to have the stored prints conserved. In September of 2010, the restored works were hung on anti-theft security hooks in the lobby of the Oscar M. Corbin Jr. City Hall, where they are now on permanent display as part of the City of Fort Myers public art collection.

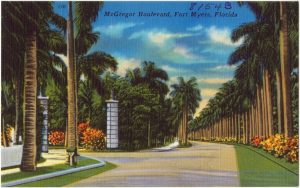

One print depicts an early image of McGregor Boulevard. Before it was widened and paved by the Estate of Tootie McGregor between 1914 and 1915, the old Wire Road served as a cattle trail connecting ranges east of present day Alva and LaBelle to the shipping pens and chutes in Punta Rassa. Until the early 1900s, it was common to see herds exceeding a thousand  head pass along present-day First Street on their way to those shipping facilities. But in 1912, Tootie McGregor Terry offered to pave the old Wire Road (which had been renamed Riverside Drive) from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa if the City and County would pay for the paving from Whiskey Creek to the train depot on Monroe and

head pass along present-day First Street on their way to those shipping facilities. But in 1912, Tootie McGregor Terry offered to pave the old Wire Road (which had been renamed Riverside Drive) from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa if the City and County would pay for the paving from Whiskey Creek to the train depot on Monroe and  present-day Main Street. Her only condition: that the road be renamed McGregor Boulevard in honor of her first husband, oil magnate Ambrose McGregor.

present-day Main Street. Her only condition: that the road be renamed McGregor Boulevard in honor of her first husband, oil magnate Ambrose McGregor.

While Tootie may have been responsible for widening, paving and renaming the road McGregor Boulevard, it was Thomas Edison who was responsible for planting the thoroughfare’s famous  royal palms. But it wasn’t as easy as it sounds at first blush. The first 1,100 palms died when Cuba imposed a quarantine due to a yellow fever scare. So did another 700 that Edison’s contractors removed from the Big Cypress. Finally, 1,300 live royals made it to town, but the City failed to take care of them and most died of neglect.

royal palms. But it wasn’t as easy as it sounds at first blush. The first 1,100 palms died when Cuba imposed a quarantine due to a yellow fever scare. So did another 700 that Edison’s contractors removed from the Big Cypress. Finally, 1,300 live royals made it to town, but the City failed to take care of them and most died of neglect.  Undaunted, Edison donated another 428 trees and residents on Second Street planted royals at their own expense.

Undaunted, Edison donated another 428 trees and residents on Second Street planted royals at their own expense.

Because of his insistence that the City make provision for taking care of the royal palms donated by Edison, James E. Hendry Jr. was appointed in 1915 to serve on the board of the City’s  first park department. During the next two years, he arranged for palms to be planted on many more streets, and in the late 1920s, he was awarded a contract by the City to plant 6,954 trees throughout the City. Extending 37 miles and encompassing 67 streets, it was the largest beautification program ever undertaken by any city in Southwest Florida and, in the process, established Fort Myers once and officially as The City of Palms.

first park department. During the next two years, he arranged for palms to be planted on many more streets, and in the late 1920s, he was awarded a contract by the City to plant 6,954 trees throughout the City. Extending 37 miles and encompassing 67 streets, it was the largest beautification program ever undertaken by any city in Southwest Florida and, in the process, established Fort Myers once and officially as The City of Palms.

April 30, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.