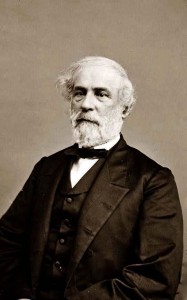

Robert E. Lee Bust

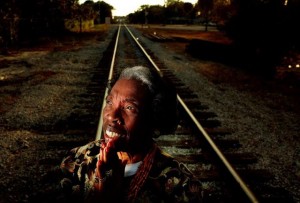

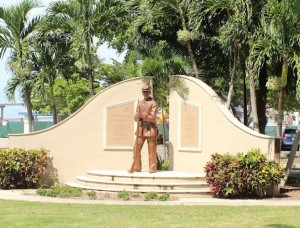

The Bust of Robert E. Lee is located in the median on Monroe Street across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage. The monument is one block south of D.J. Wilkins’ Florida Panthers and a block and a half south of the entrance into Centennial Park, where Wilkins’ The Great Turtle Chase, Uncommon Friends and Clayton are all located. Clayton is the nickname of the tribute to the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops, specifically, and all the black soldiers

The Bust of Robert E. Lee is located in the median on Monroe Street across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage. The monument is one block south of D.J. Wilkins’ Florida Panthers and a block and a half south of the entrance into Centennial Park, where Wilkins’ The Great Turtle Chase, Uncommon Friends and Clayton are all located. Clayton is the nickname of the tribute to the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops, specifically, and all the black soldiers  who served in the Union Army and Union Navy during the Civil War.

who served in the Union Army and Union Navy during the Civil War.

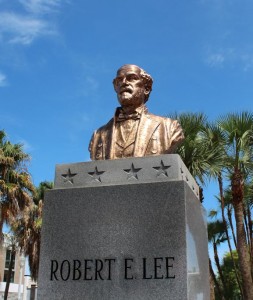

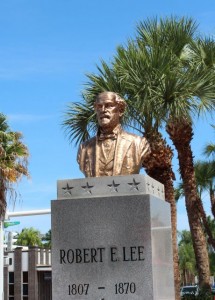

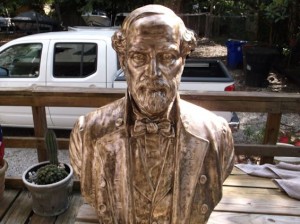

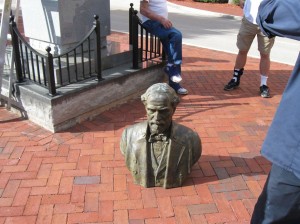

The bust of Lee was sculpted and cast in bronze by Aldo Pero in Italy and rests on a shaft of gray Georgia granite. The shaft sits on a concrete base. Inside the base are a dozen Civil War relics collected from Harper’s Ferry, Manassas, Gettysburg and several battlefields in Virginia. At the top of the pedestal, 4 five-pointed stars have been carved into each face of the capstone.

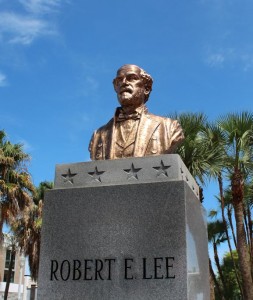

The work was commissioned at a cost of $6,000 by the  Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, chapter 1447. The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee. The monument was unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966.

Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, chapter 1447. The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee. The monument was unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966.

The relics in the base were provided by James William Clifford, a member of the Civil War Commission and 40-year collector of Civil War memorabilia. They include:

a bayonet scabbard from the Yankee Line at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia;

a 58 caliber minie bullet from the Rebel Line at the 2nd Battle of Manassas;

a 58 caliber minie bullet from the Rebel Line at the 2nd Battle of Manassas;- a 58 caliber round lead ball from the Union Line at Gettsyburg, Pennsylvania;

- a 58 caliber minie bullet from the Confederate Pattern at Hamilton’s Crossing in Fredericksburg, Virginia;

- a brass sword guard from a Confederate campsite at Centerville, Virginia;

- a 12-pound shell fragment from Yankee Line and a rusty Yankee bayonet and shenkle shell recovered 95 years after

the battle at “Bloody Angle” near Spotsylvania;

the battle at “Bloody Angle” near Spotsylvania; - a gun strap from Malver Hill, Virginia;

- a Confederate belt buckle from Rebel Line in Petersburg, Virginia;

- an iron canister shot from Rebel Line in Winchester, Virginia; and

- a 69 caliber bullet from the Yankee Line at Wilderness Battlefield in Virginia.

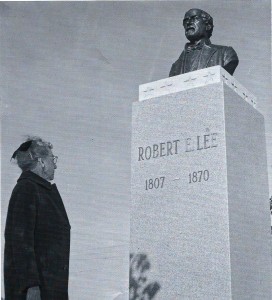

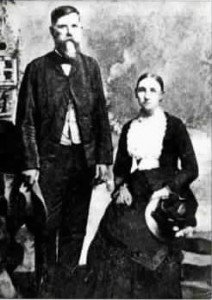

On January 6, 1966, Clifford and Edna F. Grady Roberts, Chairwoman of the Robert E. Lee Monument Fund (pictured above), placed the plastic container holding the relics within the concrete footers that support the monument “as a symbol of unity between the North and South.”

On January 6, 1966, Clifford and Edna F. Grady Roberts, Chairwoman of the Robert E. Lee Monument Fund (pictured above), placed the plastic container holding the relics within the concrete footers that support the monument “as a symbol of unity between the North and South.”

It is unclear whether the stars that circumscribe the capstone  refer to the General’s rank or represent the 11 states which originally seceded from the Union (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee), the border states of Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri (which were prevented by military occupation from voting on seceding) as well as the Arizona and Indian territories,

refer to the General’s rank or represent the 11 states which originally seceded from the Union (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee), the border states of Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri (which were prevented by military occupation from voting on seceding) as well as the Arizona and Indian territories,  officially joined the Confederacy in 1861.

officially joined the Confederacy in 1861.

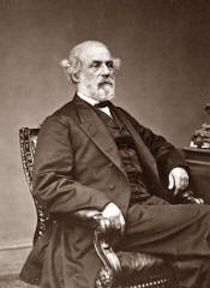

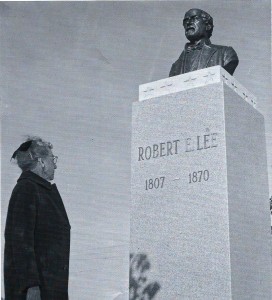

In actuality, Lee wore the 3-star insignia of a Confederate Colonel throughout the war, but the artisans who designed the memorial may have ascribed to him the insignia of a full general in the U.S. Army, namely four 5-pointed stars. “It is doubtful  that those who designed the monument had ever read G.O. No. 9, 6 June 1861, ‘Uniform and Dress of the Army,’ par. 51, which details badges of rank in the Confederacy,” notes Civil War historian and author, Dr. Ted Childress (pictured right at June 12, 2014 re-dedication ceremony). “[In all probability], they just placed the 4 stars on each side of the monument to indicate that Lee was a full general.”

that those who designed the monument had ever read G.O. No. 9, 6 June 1861, ‘Uniform and Dress of the Army,’ par. 51, which details badges of rank in the Confederacy,” notes Civil War historian and author, Dr. Ted Childress (pictured right at June 12, 2014 re-dedication ceremony). “[In all probability], they just placed the 4 stars on each side of the monument to indicate that Lee was a full general.”

On April 30, 2013, the Fort Myers Chapter of the UDC and  Maj. William Footman Camp #1950 SCV installed a scalloped black wrought iron fence around the base of the monument in order to protect the marble from skateboard damage. The work was performed free of charge by Gulf Coast Metal Works (compliments of owner Barry Crumpler).

Maj. William Footman Camp #1950 SCV installed a scalloped black wrought iron fence around the base of the monument in order to protect the marble from skateboard damage. The work was performed free of charge by Gulf Coast Metal Works (compliments of owner Barry Crumpler).

In June of 2014, the Fort Myers Chapter of the UDC and Maj. William Footman Camp #1950 SCV had the bust refurbished and restored by David N. Crowell as the bronze patina had become dull and tarnished by 48 years of exposure to direct sunlight, rain, humidity and wind. The bust was reinstalled and rededicated in a ceremony taking place on June 12, 2014.

Why Robert E. Lee

When this county was established on May 2, 1887, it was named after General Lee. Prior to that time, the land in what is now Lee, Collier and Hendry counties were all part of Monroe County. But when politicians in the far-removed county seat of Key West [a week-long round trip by schooner in those days] scornfully refused to allocate funds to rebuild the local high school after it burned down [they told the delegation sent from Fort Myers that if they were so careless as to permit a splendid $1,000 building to be destroyed by fire they didn’t deserve consideration], the citizens on this side of the state decided to break away and form their own local government.*

When this county was established on May 2, 1887, it was named after General Lee. Prior to that time, the land in what is now Lee, Collier and Hendry counties were all part of Monroe County. But when politicians in the far-removed county seat of Key West [a week-long round trip by schooner in those days] scornfully refused to allocate funds to rebuild the local high school after it burned down [they told the delegation sent from Fort Myers that if they were so careless as to permit a splendid $1,000 building to be destroyed by fire they didn’t deserve consideration], the citizens on this side of the state decided to break away and form their own local government.*

I t was Francis Asbury Hendry who led the move to name the new county after Lee, “a distinguished and laudable character whom the world has esteemed and delights to honor.” Hendry was one of the leading citizens in the growing hamlet of Fort Myers, which at the time had less than 1,500 residents. Lee was certainly one of the most famous people in the South in 1887, and was even highly regarded in the North. Hendry was an admirer who’d fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

t was Francis Asbury Hendry who led the move to name the new county after Lee, “a distinguished and laudable character whom the world has esteemed and delights to honor.” Hendry was one of the leading citizens in the growing hamlet of Fort Myers, which at the time had less than 1,500 residents. Lee was certainly one of the most famous people in the South in 1887, and was even highly regarded in the North. Hendry was an admirer who’d fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

At the dedication of the Robert E. Lee Monument on January 19, 1966, FA’s great-grandson, Lloyd G. Hendry (last photo in this section), shed light on the nomination process. “My great-grandfather made the  motion to name that new county in honor of the South’s noblest son – Robert E. Lee. To that motion there was no debate – only instant and wild acclaim.” Many of the town’s males were Confederate veterans. Appomattox and Reconstruction had not quenched the feverish loyalty and deep devotion of these men for the Confederacy’s commander-in-chief. It was in these times, and in this spirit, that Lee County selected and chose its namesake.”

motion to name that new county in honor of the South’s noblest son – Robert E. Lee. To that motion there was no debate – only instant and wild acclaim.” Many of the town’s males were Confederate veterans. Appomattox and Reconstruction had not quenched the feverish loyalty and deep devotion of these men for the Confederacy’s commander-in-chief. It was in these times, and in this spirit, that Lee County selected and chose its namesake.”

Lee’s nomination was fitting, relates Lloyd Hendry. “Lee county was born in a spirit of revolt and secession. Mass meetings were held; eloquent speeches around burning lighter-knot fires were made. Revolt was in the air. Old  grievances were pulled out and rubbed raw anew. Resolutions were adopted and petitions were signed. And when the Legislature next met, Lee County was born.”

grievances were pulled out and rubbed raw anew. Resolutions were adopted and petitions were signed. And when the Legislature next met, Lee County was born.”

But it was not Lee’s successes and failures on the battlefield that Francis Asbury Hendry hoped the citizens of Lee County would remember 125 years later. “[My great-grandfather] spoke of [Lee’s] iron integrity – his utter devotion to truth. This quality of Lee is legendary. [H]he spoke of Lee’s deep and abiding concern for his fellowmen. These are the qualities the man who named Lee County hoped the people of Lee County would emulate.”

*While Monroe County’s refusal to fund a new schoolhouse was the fuse that lighted the powder keg, residents’ dissatisfaction with being part of Monroe County was more complex. Real estate taxes went to Key West, but the commissioners there never spent one dime on roads, bridges or public improvements of any kind. In addition, a week and at least $50 in expenses were required for the trip to Key West for civil

*While Monroe County’s refusal to fund a new schoolhouse was the fuse that lighted the powder keg, residents’ dissatisfaction with being part of Monroe County was more complex. Real estate taxes went to Key West, but the commissioners there never spent one dime on roads, bridges or public improvements of any kind. In addition, a week and at least $50 in expenses were required for the trip to Key West for civil  actions or to appeal property tax assessments. “The cost of summoning witnesses to court in civil actions often was prohibitive for small litigants,” writes Karl H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers. “And for a person to go to Key West to appeal to the county commissioners for an adjustment in his taxes was absurd. Even if the got the adjustment, the cost of getting it would be more than the savings.”

actions or to appeal property tax assessments. “The cost of summoning witnesses to court in civil actions often was prohibitive for small litigants,” writes Karl H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers. “And for a person to go to Key West to appeal to the county commissioners for an adjustment in his taxes was absurd. Even if the got the adjustment, the cost of getting it would be more than the savings.”

Robert E. Lee’s record on slavery

Lauding Lee for his “iron integrity,” “utter devotion to truth” and “deep and abiding concern for his fellow men” is problematic in light of his views and actions regarding slavery. Lee’s supporters often point to the fact that in a letter he wrote to his wife in 1856, he called the institution of slavery a moral and political evil. But this comment must be viewed in its entirety. Lee went on to call the institution a necessary evil. “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially,” he continues in his letter. “The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things. How long their servitude may be necessary is known and ordered by a merciful Providence.” Lee espoused that this gradual

Lauding Lee for his “iron integrity,” “utter devotion to truth” and “deep and abiding concern for his fellow men” is problematic in light of his views and actions regarding slavery. Lee’s supporters often point to the fact that in a letter he wrote to his wife in 1856, he called the institution of slavery a moral and political evil. But this comment must be viewed in its entirety. Lee went on to call the institution a necessary evil. “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially,” he continues in his letter. “The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things. How long their servitude may be necessary is known and ordered by a merciful Providence.” Lee espoused that this gradual  process might take hundreds, even thousands, of years to accomplish.

process might take hundreds, even thousands, of years to accomplish.

Conflating the right to own slaves with religious freedom, Lee said of the abolitionists who wanted to end slavery then and there, “Is it not strange that the descendants of those Pilgrim Fathers who crossed the Atlantic to preserve their own freedom have always proved the most intolerant of the spiritual liberty of others?”

One year later, Lee’s father-in-law died, and his wife inherited 196 slaves. His father-in-law’s will mandated that they be freed within five years, but as executor of his father-in-law’s estate, Lee petitioned t he court to extend their servitude. The probate court denied his request. At that point, Lee could have released them early, but he decided instead to work them as hard as he could prior to the date of their court-ordered release in an effort to make his and his father-in-law’s estates as profitable as possible.

he court to extend their servitude. The probate court denied his request. At that point, Lee could have released them early, but he decided instead to work them as hard as he could prior to the date of their court-ordered release in an effort to make his and his father-in-law’s estates as profitable as possible.

As a slave owner, Lee was a hard and unforgiving taskmaster. Runaways were whipped mercilessly. One such runaway was Wesley Norris, who recalled that “not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done.”

Re garding them as property and their labor as a resource he was entitled to exploit, Lee had no compunction about hiring out slaves to other plantation owners even though that meant breaking up families in the process that had been together on the estate for generations. In Reading the Man, historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor writes that “by 1860, [Lee] had broken up every family but one on the estate, some of whom had been together since Mount Vernon days.” The separation of these families was one of the most unfathomably devastating aspects of slavery, and Pryor contends that the slaves in Lee’s charge as a result of his father-in-law’s death regarded him as “the worst man I ever see.”

garding them as property and their labor as a resource he was entitled to exploit, Lee had no compunction about hiring out slaves to other plantation owners even though that meant breaking up families in the process that had been together on the estate for generations. In Reading the Man, historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor writes that “by 1860, [Lee] had broken up every family but one on the estate, some of whom had been together since Mount Vernon days.” The separation of these families was one of the most unfathomably devastating aspects of slavery, and Pryor contends that the slaves in Lee’s charge as a result of his father-in-law’s death regarded him as “the worst man I ever see.”

Ironically, Lee released his father-in-law’s former slaves on the day President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Ironically, Lee released his father-in-law’s former slaves on the day President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

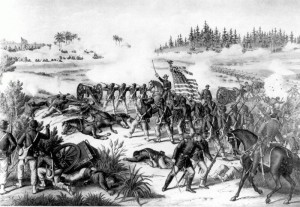

Lee’s conduct during the Civil War was even more reprehensible. During its invasion of Pennsylvania, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia enslaved free blacks it captured along the way and brought them back to the South as property. During the Battle of Crater in 1864, soldiers under Lee’s command massacred black Union soldiers who tried to surrender. Lee even refused a proposed prisoner exchange when Ulysses Grant insisted that captured black soldiers be included in the deal.

Lee’s postbellum views on equal rights for black people

The death and carnage wrought during the Civil War did not change Lee’s views about black people in any material way. He vehemently maintained that based upon wisdom and Christian principles, “you do a gross wrong and injustice to the whole Negro race in setting them free.” In fact, he argued that black people should be shipped to Africa rather than integrated into the fabric of Virginia society.

The death and carnage wrought during the Civil War did not change Lee’s views about black people in any material way. He vehemently maintained that based upon wisdom and Christian principles, “you do a gross wrong and injustice to the whole Negro race in setting them free.” In fact, he argued that black people should be shipped to Africa rather than integrated into the fabric of Virginia society.

According to correspondence collected by his own family, Lee  counseled people to hire white labor instead of freedmen, maintaining that “wherever you find the negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find a white man, you see everything around him improving.”

counseled people to hire white labor instead of freedmen, maintaining that “wherever you find the negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find a white man, you see everything around him improving.”

In one letter, Lee wrote, “You will never prosper with blacks …” and “our material, social and political interests are naturally with the whites.”

In arguing against blacks being given the right to vote, Lee told Congress that blacks lacked the intellectual capacity of whites and “could not vote intelligently.” In fact, he went on, “the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.”

In arguing against blacks being given the right to vote, Lee told Congress that blacks lacked the intellectual capacity of whites and “could not vote intelligently.” In fact, he went on, “the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power.”

His tenure as president of Washington College is just as checkered. Two lynchings occurred during this time, and Lee either punished violence toward black students extremely leniently or turned a blind eye toward it completely.

Clearly, Lee’s deep and abiding concern for his fellow men only extended to whites, and to describe Lee as an American hero requires ignoring the immense suffering for which he was personally responsible, both on and off the battlefield, not to mention overlooking his willing participation in the industry of human bondage, his betrayal of his country in defense of that institution, his postbellum hostility toward the rights of freedmen, and his indifference to his own students waging a campaign of terror against the newly emancipated.

Clearly, Lee’s deep and abiding concern for his fellow men only extended to whites, and to describe Lee as an American hero requires ignoring the immense suffering for which he was personally responsible, both on and off the battlefield, not to mention overlooking his willing participation in the industry of human bondage, his betrayal of his country in defense of that institution, his postbellum hostility toward the rights of freedmen, and his indifference to his own students waging a campaign of terror against the newly emancipated.

Timing of the monument’s installation

The Laetitia Ashmore Nutt chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was formed on February 12, 1913 and began collecting funds to install a memorial to Lee almost immediately following its inception. By 1915, the chapter had raised $1,800, but according to comments made by UDC President Lalla R. Moore following interment of the Civil War relics in the base of the statue on January 6, 1966, “the men of Fort Myers because

The Laetitia Ashmore Nutt chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was formed on February 12, 1913 and began collecting funds to install a memorial to Lee almost immediately following its inception. By 1915, the chapter had raised $1,800, but according to comments made by UDC President Lalla R. Moore following interment of the Civil War relics in the base of the statue on January 6, 1966, “the men of Fort Myers because  they couldn’t get the state to build a new courthouse tore down the old one which was made of wood and used the lumber to build the first real county hospital – at Grand and Victoria Avenues – and the chapter turned over its Lee Memorial money for use at the hospital.”

they couldn’t get the state to build a new courthouse tore down the old one which was made of wood and used the lumber to build the first real county hospital – at Grand and Victoria Avenues – and the chapter turned over its Lee Memorial money for use at the hospital.”

A second fund was started, but had only collected $500 by 1940, when the chapter again donated the funds to the hospital, this time to help furnish the nursery.

According to the current chapter of the UCD, a third and final campaign was launched in 1953. After the bust was completed, it sat in the lobby of the courthouse with a collection box for nickels, dimes, quarters and half dollars, although sometimes there were donations of $100 or more. Hundreds of businesses

According to the current chapter of the UCD, a third and final campaign was launched in 1953. After the bust was completed, it sat in the lobby of the courthouse with a collection box for nickels, dimes, quarters and half dollars, although sometimes there were donations of $100 or more. Hundreds of businesses  and citizens donated to the fund and a roster of contributors was placed in the lobby of the Lee County Courthouse as a permanent record for future generations. The memorial was finally installed early in 1966 and dedicated on January 19, 1966. The date was selected to coincide with the 159th anniversary of Lee’s birth. At the time, there were no other monuments to Robert E. Lee south of Richmond.

and citizens donated to the fund and a roster of contributors was placed in the lobby of the Lee County Courthouse as a permanent record for future generations. The memorial was finally installed early in 1966 and dedicated on January 19, 1966. The date was selected to coincide with the 159th anniversary of Lee’s birth. At the time, there were no other monuments to Robert E. Lee south of Richmond.

The period between the launch of the third fundraising campaign and installation of the monument was a watershed in civil rights case law and legislation. Even before the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education on May 18, 1954, local residents were up in arms about the impending threat to the system of segregated schools

The period between the launch of the third fundraising campaign and installation of the monument was a watershed in civil rights case law and legislation. Even before the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education on May 18, 1954, local residents were up in arms about the impending threat to the system of segregated schools  embodied in the Florida Constitution of 1885, which provided that “white and colored children shall not be taught in the same school.” Following pronouncement of the decision and taking their cues from Florida’s governor (Charley E. Brown), leading legislators and Superintendent of Public Instruction (Thomas D. Bailey), Lee County Board of Public

embodied in the Florida Constitution of 1885, which provided that “white and colored children shall not be taught in the same school.” Following pronouncement of the decision and taking their cues from Florida’s governor (Charley E. Brown), leading legislators and Superintendent of Public Instruction (Thomas D. Bailey), Lee County Board of Public  Education and the Board’s legal council adopted formal policies designed to slow walk compliance with the Brown decision.

Education and the Board’s legal council adopted formal policies designed to slow walk compliance with the Brown decision.

“For Tallahassee, as with Lee County, the die had now been cast; the reaction to Brown would be one of delay, obfuscation and obstruction,” writes Irvin D.S. Winsboro of Florida Gulf Coast University in “An Historical Perspective on Public School D esegregation in Florida: Lessons from the Past for the Present.”

esegregation in Florida: Lessons from the Past for the Present.”

At the same time, Florida, the county and Fort Myers adopted a package of racially-motivated legislation designed to restrict black rights. Chief among these was the City’s adoption in 1957 of an “at large voting system” intended to dilute black votes and all but assure the election of only white candidates  in city elections. The City followed this with an ordinance designed to block any attempts at black civil rights protests by banning gatherings at public facilities.

in city elections. The City followed this with an ordinance designed to block any attempts at black civil rights protests by banning gatherings at public facilities.

It took the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to end Florida’s and Lee County’ de facto policy of school segregation. In Lee County, the  school board proposed a plan of gradual desegregation, starting with the first grade in 1965, then proceeding grades 2 and 3 in 1966, grades 4, 5 and 6 in 1967, grades 7, 8 and 9 in 1968 and grades 10, 11 and 12 in 1969. But Rosalind Blalock’s dad had other ideas. Assisted by the President of the local chapter of the NAACP, Veronica Shoemaker, John H. Blalock filed suit in the federal district court for the middle district of

school board proposed a plan of gradual desegregation, starting with the first grade in 1965, then proceeding grades 2 and 3 in 1966, grades 4, 5 and 6 in 1967, grades 7, 8 and 9 in 1968 and grades 10, 11 and 12 in 1969. But Rosalind Blalock’s dad had other ideas. Assisted by the President of the local chapter of the NAACP, Veronica Shoemaker, John H. Blalock filed suit in the federal district court for the middle district of  Florida seeking an order enjoining the Lee County Board of Public Instruction from continuing its policy, practice, custom and usage of a dual school system.

Florida seeking an order enjoining the Lee County Board of Public Instruction from continuing its policy, practice, custom and usage of a dual school system.

On September 1, 1965, a consent decree was entered adopting an accelerated plan of desegregation. More litigation ensued all the way through December 31, 1969.  “After a decade and a half, the Lee County School Board had accepted, however unwillingly, the High Court’s decision in Brown,” Winsboro concludes. “The eradication of dual schools systems in Lee County, Florida came only after constant pressure applied by local citizens, the

“After a decade and a half, the Lee County School Board had accepted, however unwillingly, the High Court’s decision in Brown,” Winsboro concludes. “The eradication of dual schools systems in Lee County, Florida came only after constant pressure applied by local citizens, the  NAACP, the Federal Courts, and the U.S. Department of Justice. For a decade, historical and newly-promulgated measures had worked to prevent desegregation in Lee County schools. It took the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Blalock case to move a

NAACP, the Federal Courts, and the U.S. Department of Justice. For a decade, historical and newly-promulgated measures had worked to prevent desegregation in Lee County schools. It took the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Blalock case to move a  recalcitrant board away from those state guidelines on segregation towards compliance with federal law and court orders … Viewed as a case study, the experience of Lee County, Florida reflects all too poignantly what it took to move Florida from a segregationist past to an integrationist present.”

recalcitrant board away from those state guidelines on segregation towards compliance with federal law and court orders … Viewed as a case study, the experience of Lee County, Florida reflects all too poignantly what it took to move Florida from a segregationist past to an integrationist present.”

I t is against this backdrop that the Laetitia Ashmore Nutt chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy launched its third and final fundraising drive and erected the Robert E. Lee Monument in the median on Monroe Street not far from the location of the county courthouse. Mindful that the vast majority of Civil War monuments were built during the Jim Crow era of

t is against this backdrop that the Laetitia Ashmore Nutt chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy launched its third and final fundraising drive and erected the Robert E. Lee Monument in the median on Monroe Street not far from the location of the county courthouse. Mindful that the vast majority of Civil War monuments were built during the Jim Crow era of  the 1920s and the Civil Rights movement in the early 1950s and 1960s, many members of the black community in Fort Myers and Lee County at large view the Robert E. Lee Monument less as an historical marker than a memorial to black disenfranchisement, segregation and 20th century racial tension. And for that reason, some have urged that the monument be moved to a less conspicuous location.

the 1920s and the Civil Rights movement in the early 1950s and 1960s, many members of the black community in Fort Myers and Lee County at large view the Robert E. Lee Monument less as an historical marker than a memorial to black disenfranchisement, segregation and 20th century racial tension. And for that reason, some have urged that the monument be moved to a less conspicuous location.

Did Robert E. Lee ever visit the county that bears his name?

It is doubtful that Lee ever actually set foot in what is today Fort Myers.

It is doubtful that Lee ever actually set foot in what is today Fort Myers.

It is known that Lee toured large swaths of Florida in 1849 as an army engineer assigned to assist in the construction of the third order of coastal defenses. While it is entirely possible that Lee visited Sanibel Island during this time, no one has yet been able to confirm his visit. Unfortunately, none of the letters Lee wrote home during his months-long boat tour of the Florida coastline survived and the official records of Lee’s 1849 tour across Florida were lost in a fire at the War Department several years later.

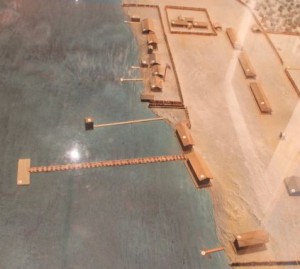

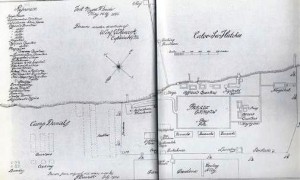

Even if he did make a stop on Sanibel Island in 1849, he would not have ventured up the Caloosahatchee River to Fort Myers because the fort did not exist back then. While an outpost by the name of Fort Harvie had been built on November 4, 1841 in what is today downtown Fort Myers, it had been abandoned on March 21, 1842 when the Second Seminole War came to an abrupt end. Fort Harvie fell into disrepair over the ensuing seven years and by the time General David Emanuel Twiggs signed the order on February 14,

Even if he did make a stop on Sanibel Island in 1849, he would not have ventured up the Caloosahatchee River to Fort Myers because the fort did not exist back then. While an outpost by the name of Fort Harvie had been built on November 4, 1841 in what is today downtown Fort Myers, it had been abandoned on March 21, 1842 when the Second Seminole War came to an abrupt end. Fort Harvie fell into disrepair over the ensuing seven years and by the time General David Emanuel Twiggs signed the order on February 14,  1850 to rebuild, expand and rename the fort, Lee had long since left the area.

1850 to rebuild, expand and rename the fort, Lee had long since left the area.

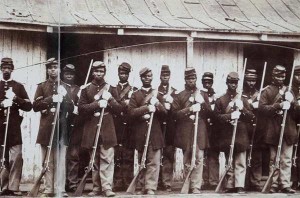

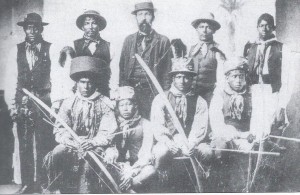

Of course, General Lee did not visit Fort Myers during the Civil War as it was a Union stronghold occupied by the Second Florida Calvary, the 110th New York Infantry and ultimately about 250 soldiers attached to Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the USTC (to whom Clayton is dedicated).

Other Tributes to Robert E. Lee

The bust is not the only tribute to Lee located within the city of Fort Myers. There is also a mosaic of Robert E. Lee and his famous horse, Traveller, in the alcove of the Lee County Bank on Hendry and First Street.

Confederate Memorial Day

Each April 26th, the Fort Myers chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Major William Footman Camp 1950 SCV observe Confederate Memorial Day by standing silent guard duty at the Robert E. Lee Memorial. Confederate Memorial Day is an official holiday in the State of Florida. Honoring those who died fighting for the Confederate States of America

Each April 26th, the Fort Myers chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Major William Footman Camp 1950 SCV observe Confederate Memorial Day by standing silent guard duty at the Robert E. Lee Memorial. Confederate Memorial Day is an official holiday in the State of Florida. Honoring those who died fighting for the Confederate States of America  during the Civil War, it is celebrated in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

during the Civil War, it is celebrated in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas.

The date for the holiday was selected by Mrs. Elizabeth Rutherford Ellis in 1866, who chose April 26 because it was the first anniversary of Confederate General Johnston’s final surrender to General Sherman at Bennett Place, North Carolina. For many in the South, that marked the official end of the Civil War. April is also Confederate Heritage Month in Lee County.

Location, Measurements and Maintenance History.

The bust’s street address is 1451 Monroe Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901

The bust’s street address is 1451 Monroe Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901- Its coordinates are longitude 26d 38′ 36.8412″ N and latitude 81d 52′ 18948″ W.

- The monument’s lower base is 13.5 inches tall and 78 inches square.

- Its upper base is 6.5 inches tall and 54.5 inches square

- The pedestal has a central shaft that is 64.5 inches tall and 30.5 inches square. It is topped

and bottomed by a 6 inch band of carved stars that is 28 inches square.

and bottomed by a 6 inch band of carved stars that is 28 inches square. - The bust is 29 inches tall, measures 28 inches across at the shoulders and is 11 inches deep at the base.

- According to the Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV, which maintains the monument, the bust has been redone

twice in the last ten years.

twice in the last ten years. - Robert E. Lee’s name is engraved in the granite pedestal, along with the years of his birth and death. That was not always the case. Originally, his name was spelled in bronze letters, but they were replaced a number of years ago with the engraving because vandals kept stealing the bronze letters.

Fast Facts

- The Laetitia Ashmore Nutt chapter of the UDC disbanded in the 1980s.

Ft. Myers Chapter 2614 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was chartered by Shellie Weber on August 18, 1998. Its members, who live in Lee, Collier, Charlotte and Glades counties, meet at Perkins Restaurant in North Fort Myers on the third Saturday of every other month from September through May at 11 a.m.

Ft. Myers Chapter 2614 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was chartered by Shellie Weber on August 18, 1998. Its members, who live in Lee, Collier, Charlotte and Glades counties, meet at Perkins Restaurant in North Fort Myers on the third Saturday of every other month from September through May at 11 a.m.- The Ft. Myers chapter of the UDC and Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV maintain the statue. Representatives are on hand every April 26 to celebrate Florida’s Confederate Memorial Day.

The National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy was organized in Nashville, TN, on September 10, 1894. At its second meeting in 1895, the organization’s name was changed to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC incorporated in the District of Columbia on July 18, 1919.

The National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy was organized in Nashville, TN, on September 10, 1894. At its second meeting in 1895, the organization’s name was changed to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC incorporated in the District of Columbia on July 18, 1919.- Francis Asbury Hendry first visited the fort from which the city takes its name in 1854, when “there was not a single settler or trace of civilization in the surrounding country.”

“The fort presented a beautiful appearance,” wrote the 20-year-old Hendry following his visit. “The grounds were tastefully laid out with shell walls and dress parade grounds and beautifully adorned with many kinds of palms. The velvety lawn was carefully attended. Special care was given to the rock rimmed riverbanks. I beheld the finest vegetable garden I ever saw. It was the property of the garrison and the vegetables were supplied to the different

“The fort presented a beautiful appearance,” wrote the 20-year-old Hendry following his visit. “The grounds were tastefully laid out with shell walls and dress parade grounds and beautifully adorned with many kinds of palms. The velvety lawn was carefully attended. Special care was given to the rock rimmed riverbanks. I beheld the finest vegetable garden I ever saw. It was the property of the garrison and the vegetables were supplied to the different  companies in any quantities needed. Near the garden there was a grove of small orange trees. The long lines of uniformed soldiers with white gloves and burnished guns, and the officers with their golden epaulettes and shining side arms were grand and magnificent to behold. Captain McKay’s store and the large commissary were well filled and tastily stored, amply supplying the soldiers’ needs. The wagon yard and stables were exceptionally well kept and the horses and

companies in any quantities needed. Near the garden there was a grove of small orange trees. The long lines of uniformed soldiers with white gloves and burnished guns, and the officers with their golden epaulettes and shining side arms were grand and magnificent to behold. Captain McKay’s store and the large commissary were well filled and tastily stored, amply supplying the soldiers’ needs. The wagon yard and stables were exceptionally well kept and the horses and  mules were as fat and sleek as corn, oats and hay could make them, and all were groomed to perfection. My pen would fail to describe the hospital with its light and airy rooms and so spotlessly clean. The officers and men were very courteous and kind, and a more comfortable and happy set of men I never saw.”

mules were as fat and sleek as corn, oats and hay could make them, and all were groomed to perfection. My pen would fail to describe the hospital with its light and airy rooms and so spotlessly clean. The officers and men were very courteous and kind, and a more comfortable and happy set of men I never saw.” The 6’1″ gray-eyed 21-year-old returned to the fort a year later as a guide to Lt. Henry Benson to ascertain if it was practical to open an overland through-route to Fort Myers.

The 6’1″ gray-eyed 21-year-old returned to the fort a year later as a guide to Lt. Henry Benson to ascertain if it was practical to open an overland through-route to Fort Myers.- Hendry next visited the fort under less hospitable circumstances. As captain of a 131-man company that he raised and commanded himself, he joined

with Major William Footman’s Cow Calvary or “Cattle Battalion” in an unsuccessful attack on Fort Myers on February 20, 1865. The operation’s objective was not control of the fort. Rather, the Cow Cavalry was desperate to put a stop to the raids the Union soldiers were making on area cattle ranchers in order to disrupt the supply of beef to Confederate forces fighting in Georgia and

with Major William Footman’s Cow Calvary or “Cattle Battalion” in an unsuccessful attack on Fort Myers on February 20, 1865. The operation’s objective was not control of the fort. Rather, the Cow Cavalry was desperate to put a stop to the raids the Union soldiers were making on area cattle ranchers in order to disrupt the supply of beef to Confederate forces fighting in Georgia and  Tennessee and cattle to blockade runners like Capt. McKay, who was operating out of Tampa Bay. In fact, Footman and Hendry would have likely burned the fort to the ground had they defeated the Union soldiers stationed there, but the Cow Calvary was repelled by elements of

Tennessee and cattle to blockade runners like Capt. McKay, who was operating out of Tampa Bay. In fact, Footman and Hendry would have likely burned the fort to the ground had they defeated the Union soldiers stationed there, but the Cow Calvary was repelled by elements of  Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. [A lengthier and more complete description of the Battle of Fort Myers can be found in the profile on D.J. Wilkins’ Clayton, a statue dedicated to the gallant soldiers of the USTC who fought in that engagement “as well as all of the 180,000 African American soldiers [and 18000 sailors] who bravely fought in the Civil War.”]

Companies D & I of the 2nd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. [A lengthier and more complete description of the Battle of Fort Myers can be found in the profile on D.J. Wilkins’ Clayton, a statue dedicated to the gallant soldiers of the USTC who fought in that engagement “as well as all of the 180,000 African American soldiers [and 18000 sailors] who bravely fought in the Civil War.”]  After the Civil War, the fort was abandoned and the Hendry Clan, whose herds, numbering 12,000 head, grazed on grasslands in the Fort Thompson area about 30 miles east of the vacated fort, moved their families to the tiny hamlet of Fort Myers rather than stay in the lonely reaches of the prairie where the cattle

After the Civil War, the fort was abandoned and the Hendry Clan, whose herds, numbering 12,000 head, grazed on grasslands in the Fort Thompson area about 30 miles east of the vacated fort, moved their families to the tiny hamlet of Fort Myers rather than stay in the lonely reaches of the prairie where the cattle  grazed. FA chose as his home one of the abandoned officer’s quarters, which he refurbished.

grazed. FA chose as his home one of the abandoned officer’s quarters, which he refurbished.- Relatives joined them, and by 1873, about ten families were living in the little settlement.

- Over the next 15 years, Hendry established a cattle export business to Cuba, refurbished the wharves and pens in Punta Rassa to support the

operation, and built his herd to 50,000 head, gaining the title of “Cattle King of South Florida.”

operation, and built his herd to 50,000 head, gaining the title of “Cattle King of South Florida.” - Hendry was one of the 45 founding fathers and chaired the meeting that resulted in the city’s incorporation on August 12, 1885.

- By 1887, the town had grown to around 1,000 people and Francis Asbury Hendry’s suggestion that the new county be named after General Lee obviously carried a lot of weight.

- Ironically, Hendry moved back to Fort Thompson in 1888 to focus on cattle breeding and his citrus groves.

- In 1895, Hendry platted LaBelle, which he named for his daughters, Laura and Belle.

- When the 764,911-acre area decided to split off and form their own government on May 11, 1923, it was named (posthumously) after Hendry (with the new local government to the south being named after Barron Collier).

2015 Articles

Restored and refurbished bust of Robert E. Lee installed one year ago (06-121-15)

One year ago today, Lee County Commissioner Cecil Pendergrass and Mayor Randy Henderson unveiled a completely restored and refurbished bust of county namesake Robert E. Lee sitting atop the gleaming gray Georgia granite pedestal in the median on Monroe Street between First and Bay.

One year ago today, Lee County Commissioner Cecil Pendergrass and Mayor Randy Henderson unveiled a completely restored and refurbished bust of county namesake Robert E. Lee sitting atop the gleaming gray Georgia granite pedestal in the median on Monroe Street between First and Bay.

Commissioned at a cost of $6,000 by the now defunct Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (chapter 1447), the bust was sculpted and cast in bronze in Italy by a sculptor named Aldo Pero. It was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee and originally unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19,  1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. But the scorching Florida sun and wind, rain and humidity took its toll over the ensuing 48 years, causing the bust to lose both its luster and definition.

1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. But the scorching Florida sun and wind, rain and humidity took its toll over the ensuing 48 years, causing the bust to lose both its luster and definition.

“So we hired an expert on marker restoration who has returned the American icon and our County’s namesake to its original look,” explained Cmdr. Robert Gates of the Major William M. Footman Camp #1950 Sons of Confederate Veterans (pictured in fourth photograph), which maintains the memorial in collaboration with the  local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Noted military historian and Estero resident Dr. Ted Childress (pictured in fifth photograph) reminded those who gathered for the unveiling and rededication why Cattle King and City Father Francis Asbury Hendry nominated Lee as namesake for the county when it was formed in 1887.

“That period in history was characterized by greed, labor unrest and political corruption and cronyism. People needed to be reminded of the collective importance of attributes such as honesty and integrity,” stated Childress, a retired Professor  Emeritus of History at Jacksonville State College. “It was not Lee’s successes and failures on the battlefield that Francis Asbury Hendry hoped the citizens of Lee County would remember 125 years later. It was Lee’s iron integrity – his utter devotion to truth.”

Emeritus of History at Jacksonville State College. “It was not Lee’s successes and failures on the battlefield that Francis Asbury Hendry hoped the citizens of Lee County would remember 125 years later. It was Lee’s iron integrity – his utter devotion to truth.”

Dr. Childress’ remarks echoed sentiments expressed more than 48 years earlier by Lloyd G. Hendry, who said at the 1966 dedication that his great-grandfather spoke of Lee’s deep and abiding  concern for his fellow men. “These are the qualities the man who named Lee County hoped the people of Lee County would emulate,” Lloyd Hendry told the crowd that gathered on January 19, 1966 for the original dedication of the bust and memorial that Lee County residents helped finance.

concern for his fellow men. “These are the qualities the man who named Lee County hoped the people of Lee County would emulate,” Lloyd Hendry told the crowd that gathered on January 19, 1966 for the original dedication of the bust and memorial that Lee County residents helped finance.

Both Commissioner Pendergrass and Mayor Henderson also emphasized the connection between the memorial and the county’s historical past. It was cattlemen like F.A. Hendry, Jake  Summerlin and William H. Towles who helped the new county and fledgling city to transition from a cow town in the last third of the 19th century into one of the leading citrus producers and tourist destination in the early 1900s.

Summerlin and William H. Towles who helped the new county and fledgling city to transition from a cow town in the last third of the 19th century into one of the leading citrus producers and tourist destination in the early 1900s.

Pendergrass was elected to the Lee County Board of County Commissioners’ District 2 seat in November 2012. In a vote of confidence from his colleagues, he was unanimously sworn in as chairman of the Board at his first meeting. He also  served as chair of the Board of Port Commissioners during his first year on the Commission. In his capacity as Lee County commissioner, Cecil serves as liaison to the Horizon Council, Public Safety Coordinating Council, Black Affairs Advisory Council, Hispanic Affairs Advisory Council, Value Adjustment Board, and Local Coordinating Board for the Transportation Disadvantaged. In addition, he serves as director on the Transportation and Expressway Authority Membership of Florida

served as chair of the Board of Port Commissioners during his first year on the Commission. In his capacity as Lee County commissioner, Cecil serves as liaison to the Horizon Council, Public Safety Coordinating Council, Black Affairs Advisory Council, Hispanic Affairs Advisory Council, Value Adjustment Board, and Local Coordinating Board for the Transportation Disadvantaged. In addition, he serves as director on the Transportation and Expressway Authority Membership of Florida  Board, and he is a member of the Lee Memorial Health System Trauma Advisory Committee.

Board, and he is a member of the Lee Memorial Health System Trauma Advisory Committee.

A resident of Fort Myers for more than 31 years, Henderson is now in his second term as the City’s mayor. He was born and raised in North Carolina where he graduated from Mars Hill College in 1979 with a BS in business administration. The mayor’s career in Fort Myers began in banking where he worked his way up to Vice-President. He  left banking in 1986 and assumed operating responsibilities for Corbin Henderson Company, a real estate firm, as president. Henderson is especially proud of the strides the city has taken to establish itself as a family-friendly destination known worldwide for its rich historical tradition, preservation and history-affirming public artworks. During his comments, Henderson reminded the crowd of other historical markers in downtown Fort Myers such as the Seminole Indian and Civil War mural in the courtyard off First that is shared by the

left banking in 1986 and assumed operating responsibilities for Corbin Henderson Company, a real estate firm, as president. Henderson is especially proud of the strides the city has taken to establish itself as a family-friendly destination known worldwide for its rich historical tradition, preservation and history-affirming public artworks. During his comments, Henderson reminded the crowd of other historical markers in downtown Fort Myers such as the Seminole Indian and Civil War mural in the courtyard off First that is shared by the  ederal courthouse and Hotel Indigo and the Don Wilkins monument in Centennial Park that pays tribute to the 178,000 black soldiers and 18,000 sailors who fought on the side of the Union in the Civil War.

ederal courthouse and Hotel Indigo and the Don Wilkins monument in Centennial Park that pays tribute to the 178,000 black soldiers and 18,000 sailors who fought on the side of the Union in the Civil War.

N.B. Depicted in 2nd photo above is Edna F. Grady, who served as chair of the monument fund committee of the Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. Please click here to read more about the chapter’s fundraising efforts, which dated back to its inception in 1913.

N.B.#2: Depicted in the third photograph is David N. Crowell, who refurbished the bust.

________________________________________________

2014 Articles

Lee bust to be reinstalled on pedestal on June 12 (06-09-14)

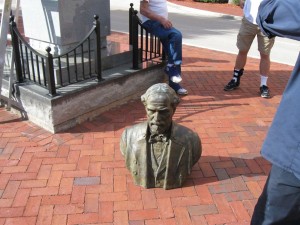

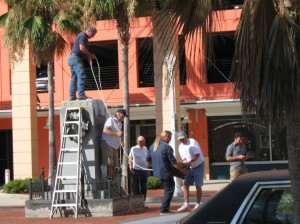

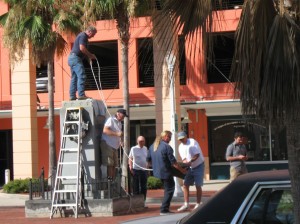

In need of some work, the Bust of Robert E. Lee located in the median on Monroe Street (across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage) was removed on May 30 by members of the Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV. Refurbishment complete, the bust will be placed back on top of its granite pedestal at 11:00 a.m. on Thursday, June 12.

In need of some work, the Bust of Robert E. Lee located in the median on Monroe Street (across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage) was removed on May 30 by members of the Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV. Refurbishment complete, the bust will be placed back on top of its granite pedestal at 11:00 a.m. on Thursday, June 12.

“The Lee bust was falling in ill repair despite several previous attempts to bring the grand marker back to it’s original stature,” notes Cmdr. Robert Gates of the Major William M. Footman Camp #1950 Sons of Confederate Veterans, which maintains the memorial in conjunction with the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “So we hired an expert on marker restoration, Mr. David N. Crowell, who

“The Lee bust was falling in ill repair despite several previous attempts to bring the grand marker back to it’s original stature,” notes Cmdr. Robert Gates of the Major William M. Footman Camp #1950 Sons of Confederate Veterans, which maintains the memorial in conjunction with the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “So we hired an expert on marker restoration, Mr. David N. Crowell, who  has returned the American icon and our County’s namesake back to the way it appeared some 48 years ago and its original look.”

has returned the American icon and our County’s namesake back to the way it appeared some 48 years ago and its original look.”

The bust was sculpted and cast in bronze in Italy by a sculptor named Aldo Pero. The work was commissioned at a cost of $6,000 by the Laetitia Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, chapter 1447 (which is now d efunct). The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee and unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the 159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. The bust rests on a shaft of gray Georgia granite which sits, in turn, on a concrete base that houses a dozen Civil War relics collected from Harper’s Ferry, Manassas, Gettysburg and several battlefields in Virginia.

efunct). The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee and unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the 159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. The bust rests on a shaft of gray Georgia granite which sits, in turn, on a concrete base that houses a dozen Civil War relics collected from Harper’s Ferry, Manassas, Gettysburg and several battlefields in Virginia.

_______________________________________________________________

Lee bust removed today for refurbishment; will return in 8-10 days (05-30-14)

In need of some work, the Bust of Robert E. Lee located in the median on Monroe Street (across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage) was removed today by members of the Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV.

In need of some work, the Bust of Robert E. Lee located in the median on Monroe Street (across from the Art League of Fort Myers and the City of Palms Parking Garage) was removed today by members of the Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV.

“The Robert E. Lee Bust is on it’s way to be refurbished,” advises Adjutant T.M. Fyock. “Several members of the Footman Camp  were on hand to complete the task of takin’ Robert down and sending him on his way to be cleaned and polished.” The Fort Myers chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV maintain the memorial, which honors Lee as the namesake of Lee County.

were on hand to complete the task of takin’ Robert down and sending him on his way to be cleaned and polished.” The Fort Myers chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Major Footman Camp 1950 SCV maintain the memorial, which honors Lee as the namesake of Lee County.

The bust was sculpted and cast in bronze in Italy by a sculptor named Aldo Pero. The work was commissioned at a cost of $6,000 by the Laetitia  Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, chapter 1447. The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee and unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the 159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. The bust rests on a shaft of gray Georgia granite which

Ashmore Nutt Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, chapter 1447. The bust was hoisted into place by the Crone Monument Company of Memphis, Tennessee and unveiled in a dedication ceremony that took place on January 19, 1966, a date selected to mark the occasion of the 159th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. The bust rests on a shaft of gray Georgia granite which  sits, in turn, on a concrete base which houses a dozen Civil War relics collected from Harper’s Ferry, Manassas, Gettysburg and several battlefields in Virginia.

sits, in turn, on a concrete base which houses a dozen Civil War relics collected from Harper’s Ferry, Manassas, Gettysburg and several battlefields in Virginia.

Wink TV was on had to cover the removal. Their coverage will air tonight at 10 and 11 p.m.

“Robert should be back up within 8 to 10 days and will be as shiny as a new penny,” Adjutant Fyock promises.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

I found the article very enlightening. Robert E. Lee was a traitor and certainly not a hero. We are the United States of America and he is a reminder of a vile time in our history when men like Lee tried and failed to create another nation. He was pro-slavery and was cruel to those that were or had been slaves.

Fort Myers in in the process of growth in the very area of this bust. Does the hotel corporation that is planning to spend millions know this history and the continued race issues that are prevalent here? I would take a step back if I were them in the hope that Lee County and Fort Myers would remove these cankers from view.

How is a man a traitor who fights for his home?

He would be warring against his kin if he chose to fight for the Fed.

There is no evidence that Lee ever was anything other than a benevolent master to his slaves. Anything else is pure calumny.

Save the South – stop cultural genocide.

To say you are ill-informed would be polite. People who do not know what they are talking about should remain silent, if only to ask questions from those who know better. You can return to your bread and circuses now. Maybe the SPLC will cut you a check if you write a blog espousing this line of thinking {which is small}. Lee was as far from being a traitor as a man could get. back before the days of big daddy federal government, people viewed themselves as citizens of their state first, the nation secondly. That whole “sovereign state” thing that that silly piece of paper called the Constitution mentioned. Lee was so cruel to his slaves, THAT HE FREED THEM BEFORE THE WAR STARTED. Of course you wouldn’t know this, because you got your education from da publik skoolz, right? It shows. Remember, if you saw or heard something on television, it must be true!

I still maintain that Lee County was only so named in order to thumb their nose at the United States and to instill an air of fear and hopelessness into the black population here at the time.

Not only should these monuments to traitors be removed. Lee County should change its name to Lincoln County.

The system of voting for county commissioners that disenfranchises Lee County’s black populaton should be dismantled and reparations should be made to the black community for generations of oppression that have followed so called “emancipation” and still largely exist today.

Excellent job Tom Hall