Millard Sheets Mosaics

On the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building next door to Val Ward Cadillac is a mosaic attributed to Millard Sheets. It is one or more than 175 stained glass, mosaics, and painted murals that Sheets’ studio created at the direction of financier Howard Ahmanson, Sr. for his now-defunct Home Savings and Loan and its parent, Savings of America.

On the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building next door to Val Ward Cadillac is a mosaic attributed to Millard Sheets. It is one or more than 175 stained glass, mosaics, and painted murals that Sheets’ studio created at the direction of financier Howard Ahmanson, Sr. for his now-defunct Home Savings and Loan and its parent, Savings of America.

“I want buildings that will be exciting seventy-five years from now,” Ahmanson told Sheets in 1953, offering him carte blanch to design the Home Savings/Savings of America brand. Ahmanson wanted his banks to be both local landmarks and gathering places within their communities. In many locales, Home Savings’ distinctive architecture could be seen up and down the avenue. Some branches boasted wide entrance plazas; others had grand lobbies with fountains and nicely manicured foliage. But what made the banks so endearing to depositors was Sheets’ focus on local history and community events. His stained glass, intricate mosaics and painted murals engendered a sense of community by depicting scenes of its people, families and local history.

“I want buildings that will be exciting seventy-five years from now,” Ahmanson told Sheets in 1953, offering him carte blanch to design the Home Savings/Savings of America brand. Ahmanson wanted his banks to be both local landmarks and gathering places within their communities. In many locales, Home Savings’ distinctive architecture could be seen up and down the avenue. Some branches boasted wide entrance plazas; others had grand lobbies with fountains and nicely manicured foliage. But what made the banks so endearing to depositors was Sheets’ focus on local history and community events. His stained glass, intricate mosaics and painted murals engendered a sense of community by depicting scenes of its people, families and local history.

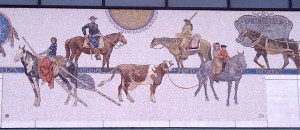

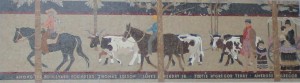

According to Fort Myers News-Press Journalist Amy Bennett Williams, the dual mosaics on the Wells Fargo building “depict the birth of Fort Myers … Scrub cattle being driven by whip-wielding cracker cowboys, Seminole Indians, a pioneer family on a paint horse, an ox cart and more.”

According to Fort Myers News-Press Journalist Amy Bennett Williams, the dual mosaics on the Wells Fargo building “depict the birth of Fort Myers … Scrub cattle being driven by whip-wielding cracker cowboys, Seminole Indians, a pioneer family on a paint horse, an ox cart and more.”  The inscription beneath the mosaics reads “McGregor Boulevard, once a cattle trail, is today lined by stately palms. The pride of Fort Myers. Among the boulevard founders: Thomas Edison, James E. Hendry, Jr., Tootie McGregor Terry, Ambrose McGregor.”

The inscription beneath the mosaics reads “McGregor Boulevard, once a cattle trail, is today lined by stately palms. The pride of Fort Myers. Among the boulevard founders: Thomas Edison, James E. Hendry, Jr., Tootie McGregor Terry, Ambrose McGregor.”

While it is true that present-day McGregor was once a dusty dirt cattle trail called Riverside Drive, the scene played out in the Wells Fargo mosaics looks more like Jane L. Hendry’s exodus from the grazing lands in the Glades country 30 miles east of Fort Myers than a cattle drive down to the stockyards in Punta Rassa, where scrub cows were loaded onto boats bound for Havana in exchange for the promise of payment in Spanish doubloons.

It was the death of Jane L. and Charles’ six-year-old daughter Esther Ann on May 17, 1873 that was, in a very real sense, responsible for the birth of Fort Myers. The tiny town had all but been abandoned the year before the little girl’s death, but immediately after the child’s crude coffin was lowered into the ground beneath a pine tree next to the Hendry’s home, Jane L. began packing the family’s possessions.

“She was moving nearer neighbors so she could have help if one of her other children, James, Alice or Roean, became sick,” explains James H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers (p. 90).

“She was moving nearer neighbors so she could have help if one of her other children, James, Alice or Roean, became sick,” explains James H. Grismer in The Story of Fort Myers (p. 90).  “Charles W. did not argue. He knew that when his Jane L. made up her mind to do a thing, she was going to do it.” Two oxcarts like the ones depicted in the mosaics held everything.

“Charles W. did not argue. He knew that when his Jane L. made up her mind to do a thing, she was going to do it.” Two oxcarts like the ones depicted in the mosaics held everything.

Although Charles and Jane L. Hendry actually settled in a log cabin at the edge of Billy’s Creek, by that summer other Hendrys began moving into Fort Myers proper. First cousin Captain F.A. Hendry led the way, rebuilding one of the officer’s quarters near the site of the present-day Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center into the family home. Another of Charles’ first cousins, W. Marion Hendry, followed with his family, choosing a site on the river east of the street that’s now named after the Hendry clan. “Three more families, all closely related to the Hendrys, soon followed,” writes Grismer. “They were the families of Jehu J. Blount, whose wife, Mary, was a sister of F.A. and Marion Hendry, and Francis J. and Augustus J. Wilson, nephews of the Hendrys.”

Although Charles and Jane L. Hendry actually settled in a log cabin at the edge of Billy’s Creek, by that summer other Hendrys began moving into Fort Myers proper. First cousin Captain F.A. Hendry led the way, rebuilding one of the officer’s quarters near the site of the present-day Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center into the family home. Another of Charles’ first cousins, W. Marion Hendry, followed with his family, choosing a site on the river east of the street that’s now named after the Hendry clan. “Three more families, all closely related to the Hendrys, soon followed,” writes Grismer. “They were the families of Jehu J. Blount, whose wife, Mary, was a sister of F.A. and Marion Hendry, and Francis J. and Augustus J. Wilson, nephews of the Hendrys.”

All were cattlemen who’d passed by the old fort on drives to Punta Rassa.

Notwithstanding the great hurricane of October 6, 1873 and Major James Evans’ claim that he’d homesteaded all of the lands occupied by the town’s early settlers years before, the Hendrys stayed and attracted dozens of cow hunters, drovers, blacksmiths, cobblers and shopkeepers, along with doctors, druggists and merchants of varying types. “Men in every line of endeavor began coming to Fort Myers,” notes Grismer. “They could make a living here while at the same time get all the benefits of a fine climate, and fish and hunt to their heart’s content. They did not come in a great migration, but a few this year, and a few next, the total always climbing.”

So Williams is right. The mural depicts the actual event that gave birth to the city we today know as Fort Myers. But the cattle trail is also part of that narrative.

The cattle trail cut through the emerging town, connecting the pasture lands and ranges in LaBelle, Fort Ogden and Alva to the cow pens and wharves downriver in Punta Rassa. Running down First, it morphed into the old Wire Road, which contained a stopover for cattle drovers that Thomas Edison purchased along with 13 acres on the river when he bought the site for his winter home and botanical research lab in 1885 from Fort Myers’ first cattleman, Samuel Summerlin. Edison erected a lodge on the property that consisted of two identical houses built side by side. He and his family occupied one. His business partner, Ezra Gilliland, occupied the other. The relationship between Gilliland and Edison would eventually deteriorate due to a bad business deal. When Edison cut off power and water to the Gilliland side of the property, Galliland decided to sell his half of the lodge. The purchasers were none other than Ambrose and Tootie McGregor.

The cattle trail cut through the emerging town, connecting the pasture lands and ranges in LaBelle, Fort Ogden and Alva to the cow pens and wharves downriver in Punta Rassa. Running down First, it morphed into the old Wire Road, which contained a stopover for cattle drovers that Thomas Edison purchased along with 13 acres on the river when he bought the site for his winter home and botanical research lab in 1885 from Fort Myers’ first cattleman, Samuel Summerlin. Edison erected a lodge on the property that consisted of two identical houses built side by side. He and his family occupied one. His business partner, Ezra Gilliland, occupied the other. The relationship between Gilliland and Edison would eventually deteriorate due to a bad business deal. When Edison cut off power and water to the Gilliland side of the property, Galliland decided to sell his half of the lodge. The purchasers were none other than Ambrose and Tootie McGregor.

In the years that followed, Edison imported more than 200 Royal Palms from Cuba, which he planted on either side of the dirt cattle trail between his estate and downtown. And tired of the dust, mud and smell of cow manure, Tootie McGregor induced the city and county in 1912 to join her in widening and paving the palm-lined road, which she had renamed McGregor Boulevard in honor of first husband Ambrose. Worth an estimated $16 million when he died of cancer in 1900, the former president of Standard Oil left Tootie one of the ten wealthiest people in the entire nation. Tootie used her largesse to help convert Fort Myers from a rough-and-tumble cow town into a modern Twentieth Century city.

In the years that followed, Edison imported more than 200 Royal Palms from Cuba, which he planted on either side of the dirt cattle trail between his estate and downtown. And tired of the dust, mud and smell of cow manure, Tootie McGregor induced the city and county in 1912 to join her in widening and paving the palm-lined road, which she had renamed McGregor Boulevard in honor of first husband Ambrose. Worth an estimated $16 million when he died of cancer in 1900, the former president of Standard Oil left Tootie one of the ten wealthiest people in the entire nation. Tootie used her largesse to help convert Fort Myers from a rough-and-tumble cow town into a modern Twentieth Century city.

This is the story cryptically encapsulated in the two small mosaics that now adorn the east facade of the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building on Cleveland, just north of College Parkway. But there remains the question of how big a role Millard Sheets played in the mosaics’ conception, fabrication and installation. That’s because the Fort Myers Savings of America branch was built in 1988, nearly eight years after Sheets retired.

This is the story cryptically encapsulated in the two small mosaics that now adorn the east facade of the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building on Cleveland, just north of College Parkway. But there remains the question of how big a role Millard Sheets played in the mosaics’ conception, fabrication and installation. That’s because the Fort Myers Savings of America branch was built in 1988, nearly eight years after Sheets retired.

Sheets Studio was still accepting and completing Home Savings & Loan and Savings of America commissions, but by 1988, Sheets’ former student at Scripps College, Susan Lautmann Hertel, and Denis O’Connor, were running the studio and executing the work. Sheets scholar Dr. Adam Arenson (who also serves as an associate history professor at the University of Texas in El Paso and is writing a book on the Home Savings mosaics and murals), notes that during this time, Hertel and O’Connor were overwhelmed by the number of commissions generated by Home Savings’ rapidly expanding parent, Savings of America. He implies that their struggles to keep up was reflected in their work, which did not enjoy the vibrant colors and complex compositions that characterize Millard Sheets’ own mosaics, and he cites by way of example a mosaic that Hertel and O’Connor did in 1986 for the Savings of America branch in Springfield, Missouri (right).

Sheets Studio was still accepting and completing Home Savings & Loan and Savings of America commissions, but by 1988, Sheets’ former student at Scripps College, Susan Lautmann Hertel, and Denis O’Connor, were running the studio and executing the work. Sheets scholar Dr. Adam Arenson (who also serves as an associate history professor at the University of Texas in El Paso and is writing a book on the Home Savings mosaics and murals), notes that during this time, Hertel and O’Connor were overwhelmed by the number of commissions generated by Home Savings’ rapidly expanding parent, Savings of America. He implies that their struggles to keep up was reflected in their work, which did not enjoy the vibrant colors and complex compositions that characterize Millard Sheets’ own mosaics, and he cites by way of example a mosaic that Hertel and O’Connor did in 1986 for the Savings of America branch in Springfield, Missouri (right).

Arenson (pictured right) writes: “During this time, O’Connor ordered mosaics to be fabricated in Italy, at less cost, via a broker named Franco Merli at NOVA Designs. (Denis segregated the records about these Italian-fabricated mosaics, either as a matter of file management or to keep this change out of the spotlight.) The work was done by Studio MosaicArt di D.Colledani-Milan. Offshoring the mosaic fabrication was cheaper, but it also led to changes in the fabrication techniques. Unfamiliarity with the themes, figures, and even animals intended by the sketches lead to discussions, in a mix of Italian and English, in the files.” It also resulted in errors. For example, the fabricators in Milan did not correctly reverse Sue Hertel’s initials on the Springfield, Missouri mosaic, and the installers neither noticed nor fixed it.

Arenson (pictured right) writes: “During this time, O’Connor ordered mosaics to be fabricated in Italy, at less cost, via a broker named Franco Merli at NOVA Designs. (Denis segregated the records about these Italian-fabricated mosaics, either as a matter of file management or to keep this change out of the spotlight.) The work was done by Studio MosaicArt di D.Colledani-Milan. Offshoring the mosaic fabrication was cheaper, but it also led to changes in the fabrication techniques. Unfamiliarity with the themes, figures, and even animals intended by the sketches lead to discussions, in a mix of Italian and English, in the files.” It also resulted in errors. For example, the fabricators in Milan did not correctly reverse Sue Hertel’s initials on the Springfield, Missouri mosaic, and the installers neither noticed nor fixed it.

While no such flaws are apparent on the mosaics on the Wells Fargo bank building, it is clear that Millard Sheets likely had no personal involvement in their design, fabrication or installation. Nevertheless, the mosaics are clearly historical, not only for the story they tell about Fort Myers’ birth and early development, but because they are part of an historic partnership between one of the nation’s early public artists and a visionary financier who was determined to use art in order to market his banks to the local community and thereby make them local landmarks and gathering spots – a concept alien to the homogeneity characterized by 21st Century bank design.

[N.B.: Adam Arenson is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Texas at El Paso and author. He is currently writing a book titled Privately Sponsored Public History, which investigates the history and family-minded art and architecture commissioned from the Millard Sheets Studio for Howard Ahmanson’s Home Savings and Loan banks, and what this artwork means to its communities to this day.]

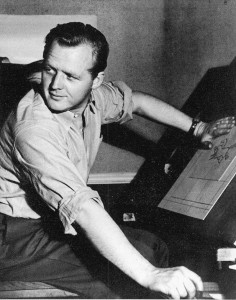

About Millard Sheets 1907-1989)

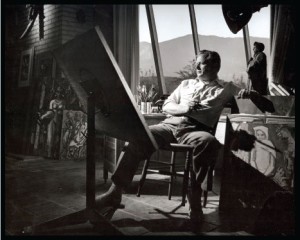

Millard Owen Sheets was a renowned 20th century artist, educator, and architectural designer. His watercolors and oil paintings were widely exhibited during his career and are included in the collections of many major museums. Yet many of Sheets best known pieces are public artworks that depict religious themes and local history in a series of connected scenes.

Millard Owen Sheets was a renowned 20th century artist, educator, and architectural designer. His watercolors and oil paintings were widely exhibited during his career and are included in the collections of many major museums. Yet many of Sheets best known pieces are public artworks that depict religious themes and local history in a series of connected scenes.

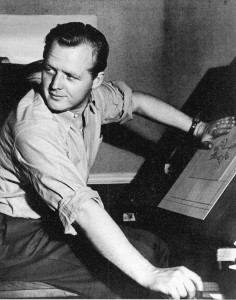

While Sheets was still a teenager, his watercolors were accepted for exhibition in the California Water Color Society’s annual shows. They were so well received that by 19, he was accepted into the Society’s membership. Sheets scholar Dr. Adam Arenson describes the Pomona Valley native as an “art wunderkind who started teaching at art school even before he graduated.” He won art contests in the 1920s, exhibiting in Paris, New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Houston, St. Louis, San Antonio, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Baltimore and Los Angeles, and in 1930, his work was selected for inclusion in the Carnegie Institute’s International Exhibition of Paintings.

Sheets became the driving force behind the revival of watercolor painting in California, viewing the medium’s quick drying, fast moving qualities as both artistically liberating and an apt reflection of the mood of a modernizing nation. He chose to capture subjects that depicted urban and rural people in humble everyday life, in landscapes and scenes inspired by California and his world travels. Arguably California’s greatest watercolorist, he was chosen by Andrew Wyeth in 2006 as one of the 20 greatest American watercolorists ever. (Others who made Wyeth’s short list include Milton Avery, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe and John Singer Sargent.)

Sheets became the driving force behind the revival of watercolor painting in California, viewing the medium’s quick drying, fast moving qualities as both artistically liberating and an apt reflection of the mood of a modernizing nation. He chose to capture subjects that depicted urban and rural people in humble everyday life, in landscapes and scenes inspired by California and his world travels. Arguably California’s greatest watercolorist, he was chosen by Andrew Wyeth in 2006 as one of the 20 greatest American watercolorists ever. (Others who made Wyeth’s short list include Milton Avery, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe and John Singer Sargent.)

After a stint at the Chouinard Art Institute, Sheets was hired to teach art at Scripps College in 1932. A scant four years later, he was appointed chair of the art department, a post he held until 1954. During his tenure, he built one of the finest art departments in the western United States. During the early 1930s, he hired artists on the West Coast to enhance federal buildings with art as part of the Public Works of Art Project (W.P.A). Prior to World War II, he designed seventeen air schools for the United States Air Force, and during the war he served as an artist correspondent for Life magazine and the United States Army Air Forces in China, India and Burma. Many of his works from this period document the scenes of famine, war and death that he witnessed.

After a stint at the Chouinard Art Institute, Sheets was hired to teach art at Scripps College in 1932. A scant four years later, he was appointed chair of the art department, a post he held until 1954. During his tenure, he built one of the finest art departments in the western United States. During the early 1930s, he hired artists on the West Coast to enhance federal buildings with art as part of the Public Works of Art Project (W.P.A). Prior to World War II, he designed seventeen air schools for the United States Air Force, and during the war he served as an artist correspondent for Life magazine and the United States Army Air Forces in China, India and Burma. Many of his works from this period document the scenes of famine, war and death that he witnessed.

As Director of Art Exhibitions for the Los Angeles County Fair from 1931 to 1956, Sheets brought world class art to Southern California. In 1938, he also became the Director of Art at Claremont Graduate School. He also Director of the Los Angeles County Art Institute (Otis College of Art and Design) from 1953 to 1961. During the early to mid 1950s, Sheets also became involved with Columbia Pictures and was technical advisor and production designer for a few years.

From the early 1950s through the late 1970s, he designed many architectural projects, including the mosaic dome and chapel at the National Shrine in Washington DC, the mosaic library tower at the University of Notre Dame (below), the mosaic facade of the Detroit Public Library (right), the mural on the Rainbow Tower of the Hilton Hotel in Honolulu, and murals for the Los Angeles City Hall. He also created mosaics, murals and sculptures and designed more than 125 Home Savings and Loan bank branches throughout California, as well as another 50 Savings of America locations in Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, New York and Florida.

From the early 1950s through the late 1970s, he designed many architectural projects, including the mosaic dome and chapel at the National Shrine in Washington DC, the mosaic library tower at the University of Notre Dame (below), the mosaic facade of the Detroit Public Library (right), the mural on the Rainbow Tower of the Hilton Hotel in Honolulu, and murals for the Los Angeles City Hall. He also created mosaics, murals and sculptures and designed more than 125 Home Savings and Loan bank branches throughout California, as well as another 50 Savings of America locations in Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, New York and Florida.

Sheets was a member of the National Watercolor Society, the American Watercolor Society, the National Academy of Design, the Society of Motion Picture Art Directors, and the Century Association. His paintings are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum in New York, the Chicago Art Institute, the National Gallery in Washington D.C., the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, and the Los Angeles County Museum.

For more detailed information, please visit http://www.californiawatercolor.com/pages/millard-sheets-biography.

About the Home Savings and Loan murals

Financier Howard Ahmanson, Sr. commissioned the first mural for his Home Savings and Loan bank buildings in 1953. Between 1954 and his death in 1989, Sheets’ studio, Millard Sheets Metal Design, completed more than 175 mosaics, painted murals and stained glass artworks for the banking chain. Of these, some 120 were located on Home Savings bank buildings throughout Southern California. Others adorned parent company Savings of America branches as far away as Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, New York and even Florida.

When the first site was almost ready, Ahmanson visited Sheets’ studio, walked around silently, and then pronounced his approval. “Sheets then proceeded to the first Home Savings and Loan bank location, at 9245 Wilshire, decorating it with a four-panel, colorfully abstract mosaic portrait facing the street,” writes Sheets scholar Dr. Adam Arenson in Huntington Frontiers. “It showed an ornate history of banking, from the Sumerians to the Renaissance, in stained glass, and the gold ‘HS&L’ tiles, for Home Savings and Loan, in columns under the windows.”

The public reaction astounded Sheets and Ahmanson. “They stood in line on Wilshire Boulevard a block and a half long waiting to put money in, in the savings and loan,” Sheets recalled. “It paid for itself in the first 10 days. It paid for the land, it paid for the building, it paid for the furnishings, landscaping. Everything.” The bank sent out questionnaires to confirm what was happening, asking, “Why did you choose Home Savings?” Customers answered, “We like to be associated with something beautiful.”

Because of the complexity, sheer number of the ensuing HS&L commissions and other commitments, Sheets hired talented artists as assistants— engineers, registered architects, draftsmen, ceramic and fiber artists, sculptors and painters, including his former student at Scripps College, Susan Lautmann Hertel, who became his assistant in all the operations of the design studio. “For a while,” Arenson notes, “Sheets asked local Pomona Valley artists, including Martha Menke Underwood, to learn how to work with the unforgiving materials of glass-tile mosaics. But in 1960, Sheets found what he needed in Denis O’Connor.”

After meticulously researching the history of a community where a mosaic was to be installed, O’Connor, Hertel and their assistants would spend weeks, even months, cutting small, textured glass tiles into the shapes desired for the mosaic, mixing shades to give the illusion of depth, movement and shadows. As they were cut, the tiles were pasted onto numbered sections of paper. “When the mosaic was ready, the entire studio would gather around as it was laid on the floor, and Sheets and the other artists would ascend a ladder to look down on the completed work, checking for any needed adjustments.”

To install each mosaic, Sheets and his crew first had to apply a base layer of cement to the bank’s travertine clading. Then they carefully inserted the mosaic tiles into the wet mortar, painted touch-ups, and sealed the joints with grout. If a tile fractured during this tedious, painstaking process, work would immediately halt as the installers made a frenzied search of their color bins for a replacement, which had to be cut and fashioned for the open spot.

Howard Ahmanson’s remarkable experiment to use community-based art to advertise his bank and win the hearts and loyalty of its depositors extended beyond his death in 1968 and the retirement of Millard Sheets in 1980. Hertel and O’Connor continued to complete Sheets’ commissions until the sale of Home Savings to Washington Mutual in 1998 (some nine years after Sheets’ death). [N.B.: After the United States Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) seized Washington Mutual Bank on September 25, 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) sold the banking subsidiaries to JP Morgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States and second largest in the world (behind HSBC).]

Survey of Sheets’ Most Renowned Public Artworks

Among the more than 200 murals he executed are:

1. The Word of Life mural on the Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame is perhaps the most seen of Sheets artwork. Visible over the north end zone of the football stadium, Fighting Irish football fans know the mural as “Touchdown Jesus.” Standing at 134 feet high by 68 feet wide, the artwork is composed of 324 panels. Of these, 189 are precast panel units, with the remaining 135 background panels being solid granite and Mankato stone. In all, 81 different stones, in 171 finishes, from 16 countries, were used in the fabrication. Among the stone Sheets used are 46 granites and syenites; 10 gabros and labradorites; 4 metamorphic gneisses; 12 serpentines; 4 crystalline marbles; and 5 limestones.

1. The Word of Life mural on the Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame is perhaps the most seen of Sheets artwork. Visible over the north end zone of the football stadium, Fighting Irish football fans know the mural as “Touchdown Jesus.” Standing at 134 feet high by 68 feet wide, the artwork is composed of 324 panels. Of these, 189 are precast panel units, with the remaining 135 background panels being solid granite and Mankato stone. In all, 81 different stones, in 171 finishes, from 16 countries, were used in the fabrication. Among the stone Sheets used are 46 granites and syenites; 10 gabros and labradorites; 4 metamorphic gneisses; 12 serpentines; 4 crystalline marbles; and 5 limestones.

“What they asked me to do was to suggest in a great processional the idea of a never-ending line of great scholars, thinkers, and teachers – saints that represented the best that man has recorded, and which are found represented in a library,” Sheets explained in an interview. “The thought was that the various periods that are suggested in the theme have unfolded in the continuous process of one generation giving to the next. I put Christ at the top with the disciples to suggest that He is the great teacher – that is really the thematic idea.”

The $200,000 mural was a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Howard V. Phalin of Winnetka, Illinois. It was installed during the spring of 1964 and was to be kept covered until the day of the formal dedication, but strong winds unveiled it a day early. The dedication ceremony was held on May 7, 1964 and included a mass and an academic convocation.

2. The murals on the Home Savings branches at the intersection in Buena Park across from Knotts Berry Farm provide an interesting contrast. The milkmaids on the first branch represent an early, cut-out-of-black-granite model for installing the mosaics, before the Sheets Studio was completing all of the work in-house. The second color-filled mural affords an imaginative look at the figures of the American West, replete with feather headdress, locomotive and grizzly prospector rendered by the Sheets Studio team of Denis O’Connor and Susan Hertel.

2. The murals on the Home Savings branches at the intersection in Buena Park across from Knotts Berry Farm provide an interesting contrast. The milkmaids on the first branch represent an early, cut-out-of-black-granite model for installing the mosaics, before the Sheets Studio was completing all of the work in-house. The second color-filled mural affords an imaginative look at the figures of the American West, replete with feather headdress, locomotive and grizzly prospector rendered by the Sheets Studio team of Denis O’Connor and Susan Hertel.

3. The Home Savings branch in Hollywood, California contains a wonderful interplay of mosaic, stained glass, sculpture, and paintings, all working together to give a feeling of the place. The installation consists of a mosaic that features 500 names in the Roll of Stars, a three-film-reel stained glass window showing the Keystone Kops, the Marx Brothers, and cowboys and Indians, a 2-ton “Flight of Europa” statue in a fountain on the plaza out front, and a painted mural honoring the site as the location where the first feature film, The Squaw Man, was filmed.

3. The Home Savings branch in Hollywood, California contains a wonderful interplay of mosaic, stained glass, sculpture, and paintings, all working together to give a feeling of the place. The installation consists of a mosaic that features 500 names in the Roll of Stars, a three-film-reel stained glass window showing the Keystone Kops, the Marx Brothers, and cowboys and Indians, a 2-ton “Flight of Europa” statue in a fountain on the plaza out front, and a painted mural honoring the site as the location where the first feature film, The Squaw Man, was filmed.

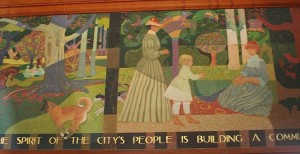

4. The Home Savings branch in San Francisco contains two narratives of the city’s history, one inside and the other out. The interior curving mural recounts centuries of history, for which Sheets provided the caption “San Francisco: Magnetic and beautiful, grew on land once home to Native Americans, host to Spanish explorers, enricher of ranchers and gold seekers. Horses, ships and the railroad brought commerce and people from every corner of the earth to build the best city by the bay. Partially destroyed by earthquake and fire, the city grew again. Victorian mansions, banking centers and hotels were built, and the legendary cable cars, parks and bridges welcomed the world. Today, the spirit of the city’s people is building a community both international and unique.” Outside, mosaic vignettes retell the city’s history, but here the background granite holds a silhouette of the city skyline. Unfortunately, the trees have grown up so tall that one must stand right under the mosaics to get a glimpse of them.

4. The Home Savings branch in San Francisco contains two narratives of the city’s history, one inside and the other out. The interior curving mural recounts centuries of history, for which Sheets provided the caption “San Francisco: Magnetic and beautiful, grew on land once home to Native Americans, host to Spanish explorers, enricher of ranchers and gold seekers. Horses, ships and the railroad brought commerce and people from every corner of the earth to build the best city by the bay. Partially destroyed by earthquake and fire, the city grew again. Victorian mansions, banking centers and hotels were built, and the legendary cable cars, parks and bridges welcomed the world. Today, the spirit of the city’s people is building a community both international and unique.” Outside, mosaic vignettes retell the city’s history, but here the background granite holds a silhouette of the city skyline. Unfortunately, the trees have grown up so tall that one must stand right under the mosaics to get a glimpse of them.

5. Though now an optometrist’s office, the Sheets Studio buildings have been preserved, from Sheets’s own office to the projection room and mosaic-composition areas in the taller building to the right. Details throughout the property–the mosaic birds, the stained glass, the terrazzo cat in the floor, the name “Millard Sheets Designs” on the travertine block–still hint at its original purpose.

5. Though now an optometrist’s office, the Sheets Studio buildings have been preserved, from Sheets’s own office to the projection room and mosaic-composition areas in the taller building to the right. Details throughout the property–the mosaic birds, the stained glass, the terrazzo cat in the floor, the name “Millard Sheets Designs” on the travertine block–still hint at its original purpose.

6. Though the interior remodelling has ruined the effect of the stained glass window, the original Home Savings branch at 9245 Wilshire Boulevard, the oldest extant collaboration between Sheets and Howard Ahmanson, remains the best place to understand how the germ of an idea grew into such a distinctive collection of art and architecture. Here sculpture, stained glass, and mosaics are on display. At 9145 Wilshire, the former Ahmanson Trust & Savings gives a good sense of what the original Sheets interior looked like (though the fountain is gone).

6. Though the interior remodelling has ruined the effect of the stained glass window, the original Home Savings branch at 9245 Wilshire Boulevard, the oldest extant collaboration between Sheets and Howard Ahmanson, remains the best place to understand how the germ of an idea grew into such a distinctive collection of art and architecture. Here sculpture, stained glass, and mosaics are on display. At 9145 Wilshire, the former Ahmanson Trust & Savings gives a good sense of what the original Sheets interior looked like (though the fountain is gone).

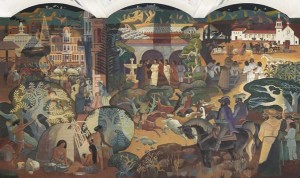

7. In 1977, the San José Mercury News commissioned artist Millard Sheets to create a 20 x 30 foot mural for the Airport as a gift to the people of San José to celebrate the City of San José’s 200th birthday and the 125th birthday of the newspaper. The mural is intended to be read counter-clockwise (see image below). Starting at the bottom left-hand corner (1) is a group of Ohlone people, the indigenous settlers of this Valley. Spanish colonists (2) shown on the bottom right. The scene shifts to the top right, presentation of (3) the original Santa Clara Mission, and then left to (4) the days of Mexican rancho life in the Valley. Moving further left, the mural depicts (5) blooming orchards, in the upper left-hand corner (6) the beginning of modernization of San José,represented by the building of San José Normal School (now San José State University). San José historic downtown 237-foot electric light tower (7), built in 1881 and demolished in 1915, is the focal point of the upper left.

7. In 1977, the San José Mercury News commissioned artist Millard Sheets to create a 20 x 30 foot mural for the Airport as a gift to the people of San José to celebrate the City of San José’s 200th birthday and the 125th birthday of the newspaper. The mural is intended to be read counter-clockwise (see image below). Starting at the bottom left-hand corner (1) is a group of Ohlone people, the indigenous settlers of this Valley. Spanish colonists (2) shown on the bottom right. The scene shifts to the top right, presentation of (3) the original Santa Clara Mission, and then left to (4) the days of Mexican rancho life in the Valley. Moving further left, the mural depicts (5) blooming orchards, in the upper left-hand corner (6) the beginning of modernization of San José,represented by the building of San José Normal School (now San José State University). San José historic downtown 237-foot electric light tower (7), built in 1881 and demolished in 1915, is the focal point of the upper left.

With the construction of Terminal B and the rerouting of roads around the airport, Terminal C was demolished and the mural had to be removed and relocated. The City of San José’s Public Art Program’s initial work began with an on-site investigation of the piece by a conservator, who made a visual inspection and tested the materials using in fabrication of the mural to understand its current condition and installation methods. The artist’s files, archived at the Smithsonian Museum, were attained to inform the process; and Millard Sheets’ family was contacted for additional perspective. With the assistance of a large round roller, the mural was peeled from the wall. Except for some difficulty with the initial glued edges, the mural sustained minimal damage. After months of carefully removing the sheetrock from the back of the canvas, the mural was reinstalled at the airport’s international gates. Sheets’ son Tony was on hand to touch up the mural and make the call on trimming that was required based on the new site.

With the construction of Terminal B and the rerouting of roads around the airport, Terminal C was demolished and the mural had to be removed and relocated. The City of San José’s Public Art Program’s initial work began with an on-site investigation of the piece by a conservator, who made a visual inspection and tested the materials using in fabrication of the mural to understand its current condition and installation methods. The artist’s files, archived at the Smithsonian Museum, were attained to inform the process; and Millard Sheets’ family was contacted for additional perspective. With the assistance of a large round roller, the mural was peeled from the wall. Except for some difficulty with the initial glued edges, the mural sustained minimal damage. After months of carefully removing the sheetrock from the back of the canvas, the mural was reinstalled at the airport’s international gates. Sheets’ son Tony was on hand to touch up the mural and make the call on trimming that was required based on the new site.

The San José International Airport mural was Sheets’ last mural.

_____________________________________________________

Former Home Savings project manager sheds light on Fort Myers’ Sheets mural (07-09-14)

On the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building next door to Val Ward Cadillac is a mosaic attributed to Millard Sheets. It is the subject of a profile in Art Southwest Florida. A few days ago, a former Home Savings national project manager discovered the profile and posted a comment that sheds light on the activities of Sheets’ studio during the time that it designed, fabricated and installed the Fort Myers mosaic.

On the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building next door to Val Ward Cadillac is a mosaic attributed to Millard Sheets. It is the subject of a profile in Art Southwest Florida. A few days ago, a former Home Savings national project manager discovered the profile and posted a comment that sheds light on the activities of Sheets’ studio during the time that it designed, fabricated and installed the Fort Myers mosaic.

The dual-panel mosaic on the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building on Tamiami Trail is one or more than 175 stained glass, mosaics, and painted

The dual-panel mosaic on the Wells Fargo Home Mortgage bank building on Tamiami Trail is one or more than 175 stained glass, mosaics, and painted  murals that Sheets’ studio created at the direction of financier Howard Ahmanson, Sr. for his now-defunct Home Savings and Loan and its parent, Savings of America. But it is unlikely that Sheets even knew about the mural, much less participated in its design, fabrication or installation. That’s because Sheets retired in 1980.

murals that Sheets’ studio created at the direction of financier Howard Ahmanson, Sr. for his now-defunct Home Savings and Loan and its parent, Savings of America. But it is unlikely that Sheets even knew about the mural, much less participated in its design, fabrication or installation. That’s because Sheets retired in 1980.

Sheets Studio continued accepting new commissions from Home Savings & Loan and Savings of America, but the work was completed by Sheets’ former student at Scripps College, Susan Lautmann Hertel, and Denis O’Connor, who took over operations following Millard’s retirement. “Millard Sheets was not involved in any of the mosaics during my tenure,” confirms Daniel Lodolo, who served as national project manager for Home Savings and

Sheets Studio continued accepting new commissions from Home Savings & Loan and Savings of America, but the work was completed by Sheets’ former student at Scripps College, Susan Lautmann Hertel, and Denis O’Connor, who took over operations following Millard’s retirement. “Millard Sheets was not involved in any of the mosaics during my tenure,” confirms Daniel Lodolo, who served as national project manager for Home Savings and  Savings of America from 1984 through 1990. “O’Connor and Hertel were commissioned by the bank at the direction of [Howard’s nephew] Mr. Bob Ahmanson [who served as an officer and director with the company until his retirement in 1995],” Lodolo adds.

Savings of America from 1984 through 1990. “O’Connor and Hertel were commissioned by the bank at the direction of [Howard’s nephew] Mr. Bob Ahmanson [who served as an officer and director with the company until his retirement in 1995],” Lodolo adds.

Sheets scholar Dr. Adam Arenson (who also serves as an associate history professor at the University of Texas in El Paso and is writing a book on the Home Savings mosaics and murals), notes that during this time, Hertel and O’Connor were overwhelmed by the number of commissions generated by Home Savings’ rapidly expanding parent, Savings of America. “During this time, O’Connor ordered mosaics to be fabricated in Italy, at less cost, via a broker named Franco Merli at NOVA Designs. The work was done by Studio MosaicArt di D.Colledani-Milan.”

But apparently Hertel and O’Connor kept that information private. “Regarding the place of manufacture,” says Lodolo, “I was told by Ms. Hertel that the pieces were cut at ‘the studio’.” Even if the mosaics were fabricated elsewhere, Hertel and O’Connor continued to personally supervise their installation on site. “I can attest that each piece was placed on the mosaic by either Hertel or O’Connor, or a crew member at the site, then erected into place,” Lodolo asserts. “As a developer and construction manager it was interesting to watch them work. One couldn’t help but think that it would have been so much easier to pre-fabricate a panel in the studio and have a small

But apparently Hertel and O’Connor kept that information private. “Regarding the place of manufacture,” says Lodolo, “I was told by Ms. Hertel that the pieces were cut at ‘the studio’.” Even if the mosaics were fabricated elsewhere, Hertel and O’Connor continued to personally supervise their installation on site. “I can attest that each piece was placed on the mosaic by either Hertel or O’Connor, or a crew member at the site, then erected into place,” Lodolo asserts. “As a developer and construction manager it was interesting to watch them work. One couldn’t help but think that it would have been so much easier to pre-fabricate a panel in the studio and have a small  crane put the mosaic in place. Their presence at the site was constant until the piece was in place. A piece like the one at Fort Myers could take at least a week to piece together, harden, set.”

crane put the mosaic in place. Their presence at the site was constant until the piece was in place. A piece like the one at Fort Myers could take at least a week to piece together, harden, set.”

“Inside the branches there was usually a mural also influenced by Millard Sheets,” Lodolo also notes. “These paintings were often contracted for with [Millard’s son] Tony Sheets.”

For nearly 20 years, Millard Sheets had a hand in the architectural design of the bank’s branch locations. “The  architecture of Millard Sheets was replaced in the 1970s, mainly by Frank Homolka and Associates,” Lodolo points out. “That firm was charged with the task of changing the direction of architecture for the buildings, but challenged to craft them in such a way as to use the major themes of the old buildings. The art, travertine, flashed walnut tile, and gold cornice banding were the ways to do that. As planning commissions and community activists came to more prominence in the 1980s, the buildings identifiable features struggled. By the time the savings branches in Upland (1988) and La Canada were built (1990), there were times when the company could hardly get its signature on a building. The marble mausoleum was a hard sell in a

architecture of Millard Sheets was replaced in the 1970s, mainly by Frank Homolka and Associates,” Lodolo points out. “That firm was charged with the task of changing the direction of architecture for the buildings, but challenged to craft them in such a way as to use the major themes of the old buildings. The art, travertine, flashed walnut tile, and gold cornice banding were the ways to do that. As planning commissions and community activists came to more prominence in the 1980s, the buildings identifiable features struggled. By the time the savings branches in Upland (1988) and La Canada were built (1990), there were times when the company could hardly get its signature on a building. The marble mausoleum was a hard sell in a  lot of cities and, had Sheets continued with Home Savings, would have left him in a position to fight for them on a routine basis. This would have been a task seemingly undignified for a man that had been so much to the State of California.”

lot of cities and, had Sheets continued with Home Savings, would have left him in a position to fight for them on a routine basis. This would have been a task seemingly undignified for a man that had been so much to the State of California.”

Howard Ahmanson’s remarkable experiment to use community-based art to advertise his bank and win the hearts and loyalty of its depositors extended beyond his death in 1968 and the retirement of Millard Sheets in 1980. Hertel and O’Connor continued to complete Sheets’ commissions until the sale of Home Savings to Washington Mutual in 1998 (some nine years after Sheets’ death). [N.B.: After the United States Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) seized Washington Mutual Bank on September 25, 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) sold the banking subsidiaries to JP Morgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States and second largest in the world (behind HSBC).]

______________________________________________________

Other Articles and Links.

- How an artist and financier created a public art legacy (08-25-13)

- Fort Myers ‘Sheets’ mosaics depict the birth of Fort Myers (08-24-13)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Some of his mosaics are in danger. The bank he decorated at Garnet Street in San Diego is for sale. It has other art from the Claremont group inside as well.