The cruel fate of Anne Frank, her sister Margot and Mrs. Van Dann

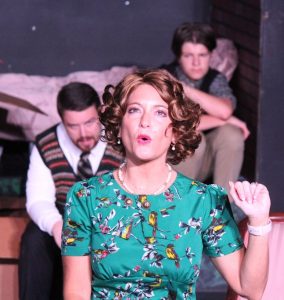

On stage through August 28 at Fort Myers Theatre is the Frances Goodrich adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank. An impassioned drama about the lives of eight people hiding from the Nazis in a concealed storage attic, The Diary of Anne Frank captures the claustrophobic realities of their daily existence–their fear, their hope, their laughter, their grief.

On stage through August 28 at Fort Myers Theatre is the Frances Goodrich adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank. An impassioned drama about the lives of eight people hiding from the Nazis in a concealed storage attic, The Diary of Anne Frank captures the claustrophobic realities of their daily existence–their fear, their hope, their laughter, their grief.

For nearly two years, they prayed incessantly for deliverance, either by the Dutch monarchy or the Allies, and their  hopes were buoyed by news that an expeditionary force consisting of Americans, British and Canadian soldiers had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. They were convinced that Allied forces would reach Amsterdam in a mere matter of weeks. But, alas, Canadian forces would not reach Amsterdam until May 8, 1945 – eight days after Adolf Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker and three days after the Germans had surrendered to the Allies in the eastern part of the

hopes were buoyed by news that an expeditionary force consisting of Americans, British and Canadian soldiers had landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. They were convinced that Allied forces would reach Amsterdam in a mere matter of weeks. But, alas, Canadian forces would not reach Amsterdam until May 8, 1945 – eight days after Adolf Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker and three days after the Germans had surrendered to the Allies in the eastern part of the  Netherlands (a date that is remembered now as Bevrijdinsdag or Liberation Day).

Netherlands (a date that is remembered now as Bevrijdinsdag or Liberation Day).

By then, all the occupants of the annex except Otto Frank had been dead for several months. As Otto Frank reveals in the heartrending monologue he delivers at the end of the play, the eight were herded into cattle wagons and taken from Westerbork Kamp to Auschwitz, where the men were separated from the women. Edith Frank and her daughters, Margot  and Anne, and Mrs. Van Dann were all taken to Birkenau, which had been created as an extension of Auschwitz in a birch forest in the spring of 1942.

and Anne, and Mrs. Van Dann were all taken to Birkenau, which had been created as an extension of Auschwitz in a birch forest in the spring of 1942.

It was there, in January of 1945, that Edith Frank died of starvation. She died alone.

Margot and Anne were sent to Bergen-Belsen the previous October, where they were surprised to find Mrs. Van Dann. But it was a bitter reunion. Bergen-Belsen was perhaps the worst of the Nazi death  camps.

camps.

“Many people talk about Auschwitz, it was a horrible camp,” said Holocaust survivor Violette Fintz forty years later. “But Belsen, no words can describe it. There was no need to work as we were just put there with no food, no water, no anything, eaten by the lice … [surrounded by] piles of bodies decomposing, in fact about a mile of bodies.”

Margot fell out of her bunk in February of 1945 and was in such  a weakened and emaciated state that she died of shock after hitting the floor. A few days later, Anne died of typhus, a bacterial infection she got from the lice. The end was horrific. In addition to the fever, chills, head and body aches and a rash that covered her entire body, the poor teen suffered from nausea, vomiting, stupor and delirium. Like Margot, it was the shock that finally took her.

a weakened and emaciated state that she died of shock after hitting the floor. A few days later, Anne died of typhus, a bacterial infection she got from the lice. The end was horrific. In addition to the fever, chills, head and body aches and a rash that covered her entire body, the poor teen suffered from nausea, vomiting, stupor and delirium. Like Margot, it was the shock that finally took her.

There’s no record of Mrs. Van Dann’s cause of death, but if  typhus didn’t claim her, starvation surely did. When British troops finally entered Belsen on April 17, 1945, they found ten thousand unburied bodies. Most were victims of starvation. Three hundred inmates died each day during the week following the camp’s liberation. Sixty a day continued to die for the balance of that month in spite of the intervention of British medical personnel and the availability of food and water. All but a few of the camp’s internees were so diseased and debilitated that they were barely able to move, never mind crawl out of their straw bunks.

typhus didn’t claim her, starvation surely did. When British troops finally entered Belsen on April 17, 1945, they found ten thousand unburied bodies. Most were victims of starvation. Three hundred inmates died each day during the week following the camp’s liberation. Sixty a day continued to die for the balance of that month in spite of the intervention of British medical personnel and the availability of food and water. All but a few of the camp’s internees were so diseased and debilitated that they were barely able to move, never mind crawl out of their straw bunks.  It was so bad in the camp that British doctors drew a red cross on the foreheads of the few they thought had a chance of surviving.

It was so bad in the camp that British doctors drew a red cross on the foreheads of the few they thought had a chance of surviving.

The point of the preceding paragraphs is not just to shock and scandalize. For time out of memory, people have scapegoated and persecuted the “other,” those who believe, behave or love differently. The precondition for doling out inhumane treatment, however, is dehumanization, and that continues to this very day – not only abroad, but right here in the United States. Jews, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community and immigrants are still targeted. Antisemitism and hate crimes are once again on the rise.  And in U.S. border detention centers crowded with migrant children, disease is rampant (not just COVID, but strep throat and typhus-causing lice outbreaks); food is undercooked and unsafely prepared; shoes and clean clothing in short supply; and reports of sexual abuse abound.

And in U.S. border detention centers crowded with migrant children, disease is rampant (not just COVID, but strep throat and typhus-causing lice outbreaks); food is undercooked and unsafely prepared; shoes and clean clothing in short supply; and reports of sexual abuse abound.

Anne Frank was an aspiring writer, not an activist in the manner of Greta Thunberg.  But Miep Gies was. In her later years, Miep lectured on Anne Frank’s legacy and the lessons taught by the Holocaust. While Director Kristen Wilson and each member of her Anne Frank cast surely has a list of life lessons they hope audience members take away from the show, one that Miep Gies would especially espouse is that every one of us has a sacred duty to speak up and speak out against prejudice, inequality and inhumanity whenever and wherever it raises its ugly head.

But Miep Gies was. In her later years, Miep lectured on Anne Frank’s legacy and the lessons taught by the Holocaust. While Director Kristen Wilson and each member of her Anne Frank cast surely has a list of life lessons they hope audience members take away from the show, one that Miep Gies would especially espouse is that every one of us has a sacred duty to speak up and speak out against prejudice, inequality and inhumanity whenever and wherever it raises its ugly head.

Standing mute in the presence of racially or religiously prejudiced statements, tropes, jokes and memes cloaks them with an aura of wink-and-nod acceptability. That emboldens those who utter them to vilify and dehumanize “the other” which, if left unchecked, may inevitably lead to a new Auschwitz, Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen.

tropes, jokes and memes cloaks them with an aura of wink-and-nod acceptability. That emboldens those who utter them to vilify and dehumanize “the other” which, if left unchecked, may inevitably lead to a new Auschwitz, Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen.

“I feel strongly that we should not wait for our political leaders to make this world a better place,” said Miep near the end of her long and well-lived life.

More,  we must create a cultural climate in which political leaders understand and accept that prejudice, inequality and inhumanity are not acceptable and will not be countenanced in any way, shape or form.

we must create a cultural climate in which political leaders understand and accept that prejudice, inequality and inhumanity are not acceptable and will not be countenanced in any way, shape or form.

That, truly, is the lesson taught by The Diary of Anne Frank.

August 15, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.