Holocaust survivor Steen Metz determined to keeping victims’ stories alive

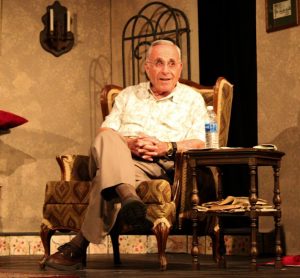

Holocaust survivor Steen Metz will speak at The Laboratory Theater of Florida at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, April 2 as part of the Theater’s expanding tolerance and cultural education programming. His question and answer discussion coincides with Holocaust Remembrance Month in April.

Holocaust survivor Steen Metz will speak at The Laboratory Theater of Florida at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, April 2 as part of the Theater’s expanding tolerance and cultural education programming. His question and answer discussion coincides with Holocaust Remembrance Month in April.

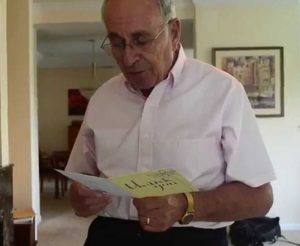

Now 79, Metz spends his senior years recounting his story at schools, libraries, churches, senior centers and civic organizations  throughout the country every chance he gets. It wasn’t always that way. Prior to 2011, he kept his experiences at Theresienstadt private. Like many Holocaust survivors, he found it impossible to talk about what happened in the camps, even to his wife, children and grandchild. But in 2011, he decided to write his memoirs, which he’s compiled in a self-published book

throughout the country every chance he gets. It wasn’t always that way. Prior to 2011, he kept his experiences at Theresienstadt private. Like many Holocaust survivors, he found it impossible to talk about what happened in the camps, even to his wife, children and grandchild. But in 2011, he decided to write his memoirs, which he’s compiled in a self-published book  titled A Danish Boy in Theresienstadt. Now, it’s Steen’s life mission to share his experiences with as many people as he can reach.

titled A Danish Boy in Theresienstadt. Now, it’s Steen’s life mission to share his experiences with as many people as he can reach.

“I’m determined to keep the victims’ memories and stories alive.”

We know today that this is what Shoah victims wanted, nay, demanded. Perhaps this sentiment was best expressed by a young girl in Carpathorussia, who wrote in her brother’s prayer book  as the Germans came to arrest her and the remainder of her family, “Whoever will find this prayer book, give it to my beloved brother, Rabbi Joshua Zeitman. The murderers are in our village. They are in the next home … Please don’t forget us! And don’t forget our murderers! They …..”

as the Germans came to arrest her and the remainder of her family, “Whoever will find this prayer book, give it to my beloved brother, Rabbi Joshua Zeitman. The murderers are in our village. They are in the next home … Please don’t forget us! And don’t forget our murderers! They …..”

Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal was present when the Rabbi accidentally happened upon the prayer book in a castle in Villach in Carinthia. It was there among thousands of Jewish books that Hitler intended to display after the war in museums and libraries as “artifacts of an extinct race.”  Said Wiesenthal years later, “This was not only a message of a sister to a brother or of a Jewish woman to a rabbi. This was a message to me: from the millions who died to us, the survivors. It could have been written by a Czech woman in Lidice, from a Frenchwoman in Oradour, from an Italian woman in Marzabotto. For me, this was the last will and testament of eleven million dead and, in the car on the way back to Linz, I decided to carry out this bequest.”

Said Wiesenthal years later, “This was not only a message of a sister to a brother or of a Jewish woman to a rabbi. This was a message to me: from the millions who died to us, the survivors. It could have been written by a Czech woman in Lidice, from a Frenchwoman in Oradour, from an Italian woman in Marzabotto. For me, this was the last will and testament of eleven million dead and, in the car on the way back to Linz, I decided to carry out this bequest.”

Each survivor faces the past and confronts the future with a burden that cannot be fully appreciated by those who did not go through the  torment of, or immediately following, the Holocaust. The pain of not knowing what happened to family and friends can never be assuaged. “For those who survive, it mingles and sometimes overwhelms the feeling of personal guilt for survival,” writes Martin Gilbert in The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War.

torment of, or immediately following, the Holocaust. The pain of not knowing what happened to family and friends can never be assuaged. “For those who survive, it mingles and sometimes overwhelms the feeling of personal guilt for survival,” writes Martin Gilbert in The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War.

For decades, many survivors like Steen Metz found it too painful to  share their stories – or even those of lost friends and relatives. Instead, they threw themselves into the struggle to adapt to new societies, learn new languages, earn a living and bring up families of their own. It’s not that they were too busy to engage in retrospection. They preferred the challenges of the present to the torment of the past.

share their stories – or even those of lost friends and relatives. Instead, they threw themselves into the struggle to adapt to new societies, learn new languages, earn a living and bring up families of their own. It’s not that they were too busy to engage in retrospection. They preferred the challenges of the present to the torment of the past.

But the cries from mass and unmarked graves grew louder with each passing year.

“Please don’t forget us! And don’t forget our murderers!”

There was a moral imperative, Martin Gilbert concludes, quoting Theresienstadt and Auschwitz survivor Zdenek Lederer, who opined that throughout the ages, it has been the lot of the Jews to deliver to men a warning. “This warning, seen so starkly in the years of the Holocaust, is a clear one: violence is, in the end, self-destructive, power futile, and the human spirit unconquerable.”

There was a moral imperative, Martin Gilbert concludes, quoting Theresienstadt and Auschwitz survivor Zdenek Lederer, who opined that throughout the ages, it has been the lot of the Jews to deliver to men a warning. “This warning, seen so starkly in the years of the Holocaust, is a clear one: violence is, in the end, self-destructive, power futile, and the human spirit unconquerable.”

With each passing year, the Holocaust is being confined inexorably to the sanitized annals of history, “increasingly distant, remote, forgotten; a chapter, reduced to a page, shortened to a paragraph, relegated to a footnote,” Gilbert observes. “Yet it must still be remembered in each generation for what it was, an unprecedented explosion of evil over good …

inexorably to the sanitized annals of history, “increasingly distant, remote, forgotten; a chapter, reduced to a page, shortened to a paragraph, relegated to a footnote,” Gilbert observes. “Yet it must still be remembered in each generation for what it was, an unprecedented explosion of evil over good …  To die with dignity was in itself courageous. To resist the dehumanizing, brutalizing force of evil, to refuse to be abased to the level of animals, to live through the torment, to outlive the tormentors, these too were courageous. Merely to give witness by one’s own testimony was, in the end, to contribute to a moral victory. Simply to survive was a victory of the human spirit.”

To die with dignity was in itself courageous. To resist the dehumanizing, brutalizing force of evil, to refuse to be abased to the level of animals, to live through the torment, to outlive the tormentors, these too were courageous. Merely to give witness by one’s own testimony was, in the end, to contribute to a moral victory. Simply to survive was a victory of the human spirit.”

It is this quantum of victory that will be on display on April 2 at the Laboratory Theater of Florida when Steen Metz speaks in observance of Holocaust Remembrance Month.

April 1, 2018.

April 1, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.