‘Doubt’ is itself a parable, a modern-day morality play, of sorts

The Broadway revival of Doubt: A Parable closed on April 21. The Pulitzer Prize and Emmy-winning drama opened May 3rd at Golden Gate Community Center in Naples.

The Broadway revival of Doubt: A Parable closed on April 21. The Pulitzer Prize and Emmy-winning drama opened May 3rd at Golden Gate Community Center in Naples.

Studio Players Director Anna Segreto says that local audiences are in for a theatrical treat.

“[The play] escalates scene by scene by scene, and as each scene unfolds, it becomes more and more intense until …  the next to the last scene, Scene 8, when the swords clash,” Segreto notes. “That kind of a theatrical experience is rare, and I think that in its rarity, the audience will be absorbed by it.”

the next to the last scene, Scene 8, when the swords clash,” Segreto notes. “That kind of a theatrical experience is rare, and I think that in its rarity, the audience will be absorbed by it.”

The storyline revolves around Sister Aloysius. She’s the abrasive principal of an all-boys Catholic grammar school in the Bronx. She becomes convinced that the charismatic parish priest is sexually abusing the school’s sole Black student. Lacking any concrete evidence to support her suspicions, the headmistress embarks upon an inquisition to prove what she already knows to be the truth with every fiber of her habit.

the charismatic parish priest is sexually abusing the school’s sole Black student. Lacking any concrete evidence to support her suspicions, the headmistress embarks upon an inquisition to prove what she already knows to be the truth with every fiber of her habit.

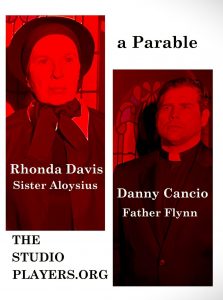

Rhonda Davis is memorable in the role of Sister Aloysius.

She tries hard to be Christian in her description of her character.

“Sister Aloysius is a very determined woman. A very strong, somebody who knows she’s right – whether she’s right or not – she knows she’s right and she does everything she can to put forward whatever it is that she thinks is right …. But she isn’t warm and toasty. If you’re looking for warm and toasty, she’s not the nun for you.”

is a very determined woman. A very strong, somebody who knows she’s right – whether she’s right or not – she knows she’s right and she does everything she can to put forward whatever it is that she thinks is right …. But she isn’t warm and toasty. If you’re looking for warm and toasty, she’s not the nun for you.”

In an early scene, she reduces one of her teachers, Sister James, to tears with her biting  critique of the younger nun’s theatrical teaching style. But it is actually Sister James who gives impetus to Sister Aloysius’ suspicions.

critique of the younger nun’s theatrical teaching style. But it is actually Sister James who gives impetus to Sister Aloysius’ suspicions.

- Sister James: I don’t have any evidence. I’m not at all certain that anything happened.

- Sister Aloysius: We can’t wait for that.

- Sister James: But maybe it’s nothing.

- Sister Aloysius: Then it’s nothing. I wouldn’t mind being wrong, but I

doubt I am.

doubt I am.

Sister Aloysius is motivated by a sense of responsibility not only to protect the children in her charge, but the reputation of the Catholic Church itself. But Sister Aloysius is also biased. This is a time in the Church’s history where it shifted from Latin to English in its services, gave a larger role to lay people and opened its windows onto the modern world. Sister Aloysius finds these changes repugnant.

“Primarily, she’s a traditionalist,” explains Rhonda Davis. “The Second Vatican Council came along and was going to modernize the Church, but Sister Aloysius is still part of the pre-Second Vatican in the way that she thinks about things, the way she approaches things.”

“Primarily, she’s a traditionalist,” explains Rhonda Davis. “The Second Vatican Council came along and was going to modernize the Church, but Sister Aloysius is still part of the pre-Second Vatican in the way that she thinks about things, the way she approaches things.”

Father Brenden Flynn is emblematic of this warmer, more modern Church. The boys’ basketball coach, he establishes a warm and supportive rapport with the kids on the team, and he takes a special interest in the school’s sole Black student, who is having trouble not only in the otherwise all-white school, but at home as well.

boys’ basketball coach, he establishes a warm and supportive rapport with the kids on the team, and he takes a special interest in the school’s sole Black student, who is having trouble not only in the otherwise all-white school, but at home as well.

The priest explains to Sister Aloysius that he’s merely trying to help the boy work through some of his problems. But he declines to reveal any confidences the boy may have revealed to him. He asks the nun for the benefit of the doubt. But Aloysius regards him with the same skepticism and suspicion she has about the changes occurring in the church. Operating from the premise that neither priests nor nuns should play any role in the personal lives of the students, she sees his interest in the child as innuendo of wrongdoing.

the boy may have revealed to him. He asks the nun for the benefit of the doubt. But Aloysius regards him with the same skepticism and suspicion she has about the changes occurring in the church. Operating from the premise that neither priests nor nuns should play any role in the personal lives of the students, she sees his interest in the child as innuendo of wrongdoing.

Instead of dropping the matter, Sister Aloysius calls in the boy’s mother, but she  flatly refuses to help the nun prove her case.

flatly refuses to help the nun prove her case.

“Sister Aloysius is taken aback,” Rhonda Davis observes. “She is really quite stunned at her interaction with Mrs. Muller, who seems to her to be a very nice woman. She thinks this is someone she can [bring around to her way of thinking]. But it doesn’t work out the way that Sister Aloysius expected.”

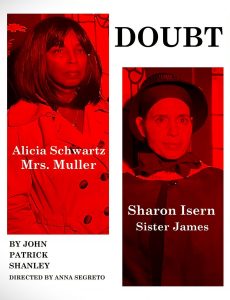

Alicia Schwartz, who plays the mom, explains why.

Alicia Schwartz, who plays the mom, explains why.

“The only thing she sees is a man as a father figure, a man that’s protecting her son in the school. That’s what Mrs. Muller is looking at. She’s not looking at it as there may be abuse ‘cause there is some doubt there. There may not be any abuse.”

Besides, if the allegations are true, it’s her son that will suffer the repercussions. He will be ridiculed and further ostracized by his white classmates. He will likely  lose the opportunity to get into a good high school and college after that. And there will be the implication that he’s gay, which will place his life in jeopardy from his physically abusive father.

lose the opportunity to get into a good high school and college after that. And there will be the implication that he’s gay, which will place his life in jeopardy from his physically abusive father.

Each of these factors weigh into the mother’s decision not to cooperate. “It’s only until June, then we’re out of here,”  she deflects. In her world, she and people of color have weathered so much worse.

she deflects. In her world, she and people of color have weathered so much worse.

Doubt opens with a scene in which Father Flynn presents a modern-day parable about a sailor lost at sea. Similarly, as its very title connotes, the play itself is a modern day parable – about our responsibility to protect members of marginalized groups,  be they people of color or those in the LGBTQ community. But that responsibility must be tempered by the Biblical stricture against bearing false witness.

be they people of color or those in the LGBTQ community. But that responsibility must be tempered by the Biblical stricture against bearing false witness.

Where might this modern day parable apply? In the corporate world or a media outlet in which a new hire informs Human Resources that a popular corporate officer or broadcaster who’s the face of the franchise may  be taking advantage of a Dreamer, a trans person or a person of color?

be taking advantage of a Dreamer, a trans person or a person of color?

Viewed from within this framework, Doubt is not just a story about pedophilia in the Catholic Church. It is a modern day morality story.

MORE INFORMATION:

- Go here for play dates, times and a full cast list.

- Thematically, Doubt examines how people deal with feelings of

uncertainty and skepticism, especially where decisions need to be made based on imperfect information.

uncertainty and skepticism, especially where decisions need to be made based on imperfect information. - In his preface to the script for Doubt, playwright John Patrick Shanley offers a different slant on the meaning of his parable. “We are living in a culture of extreme advocacy, of confrontation, of judgment, and of verdict. Discussion has given way to debate. Communication has become a contest of wills. Public talking has become obnoxious and insincere. Why?

Maybe it’s because deep down under the chatter we have come to a place where we know that we don’ know … anything. But nobody’s willing to say that.” This is Doubt – so often experienced initially as weakness – but the predicate for profound change.

Maybe it’s because deep down under the chatter we have come to a place where we know that we don’ know … anything. But nobody’s willing to say that.” This is Doubt – so often experienced initially as weakness – but the predicate for profound change. - Parables, of course, are subject to varying interpretation, and Shanley also concedes that his story applies to those responsible for safeguarding us from those

“who choose to hunt us. Of course, Doubt is confined to predatory priests operating under the protection of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. “When trust is the order of the day, predators are free to plunder,” Shanley writes. “And plunder they did. As the ever widening Church scandals reveal, the hunters had a field day. And the shepherds, so invested in the surface, sacrificed actual good for perceived virtue.” But this lesson

“who choose to hunt us. Of course, Doubt is confined to predatory priests operating under the protection of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. “When trust is the order of the day, predators are free to plunder,” Shanley writes. “And plunder they did. As the ever widening Church scandals reveal, the hunters had a field day. And the shepherds, so invested in the surface, sacrificed actual good for perceived virtue.” But this lesson  has wide application to so many other settings, from institutions of higher learning like colleges and universities, the entertainment industry that gave rise to the “Me Too” movement in 2017, and the realms of powerful public corporations and media outlets, which have seen the discharge of media moguls such as Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Matt Lauer and Harvey Weinstein amidst allegations of sexual misconduct.

has wide application to so many other settings, from institutions of higher learning like colleges and universities, the entertainment industry that gave rise to the “Me Too” movement in 2017, and the realms of powerful public corporations and media outlets, which have seen the discharge of media moguls such as Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Matt Lauer and Harvey Weinstein amidst allegations of sexual misconduct. - Like a jury,

audience members are left to draw their own conclusions about Father Flynn’s guilt or innocence. “I’ve watched a lot of interviews of John Patrick Shanley on YouTube,” says Director Anna Segreto. “He never, ever says whether or not Father Flynn is guilty or innocent. He refuses. He refuses to say it. The basic theme or themes are who speaks truth, who seeks truth and do they find it. And that’s for both Father Flynn and Sister Aloysius.

audience members are left to draw their own conclusions about Father Flynn’s guilt or innocence. “I’ve watched a lot of interviews of John Patrick Shanley on YouTube,” says Director Anna Segreto. “He never, ever says whether or not Father Flynn is guilty or innocent. He refuses. He refuses to say it. The basic theme or themes are who speaks truth, who seeks truth and do they find it. And that’s for both Father Flynn and Sister Aloysius.  It applies to both of them. And that’s the way the play is written. And that’s why it’s called Doubt.”

It applies to both of them. And that’s the way the play is written. And that’s why it’s called Doubt.” - There exist many reasons to see this play. The play is well-structured and beautifully written. The actors are accomplished. The venue is intimate. But Rhonda Davis, who plays Sister Aloysius, offers this insight: “This is an opportunity to watch some theater that will make you think. There really is a battle … that goes on.

It’s a he said/she said kind of a thing that happens, and you get to the end of the play and the question is ‘Who’s right?’ You will have one answer and the person sitting next to you will likely have a different answer, and you’ve seen the same play. Some of that is because of what you bring in when you come to see it. Some it is the way you’re affected by the actors on the stage. So I think if you’re looking for something exciting to do that will really make you think, it’s a very fast 90-minute play that you will leave saying ‘Huh, I’ve learned something today’ or ‘This gives me something

It’s a he said/she said kind of a thing that happens, and you get to the end of the play and the question is ‘Who’s right?’ You will have one answer and the person sitting next to you will likely have a different answer, and you’ve seen the same play. Some of that is because of what you bring in when you come to see it. Some it is the way you’re affected by the actors on the stage. So I think if you’re looking for something exciting to do that will really make you think, it’s a very fast 90-minute play that you will leave saying ‘Huh, I’ve learned something today’ or ‘This gives me something to think about today or talk about today with somebody else.’ So I think it’s fun for that reason.”

to think about today or talk about today with somebody else.’ So I think it’s fun for that reason.” - Actor Alicia Schwartz points out that the year in which the play is set, 1964, was not only a time of great change within the Catholic Church, it was a watershed year during the Civil Rights movement. Schools were being integrated. Jim Crow was under attack. And thanks to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African Americans were winning access for the very first time to restaurants, transportation and other public facilities. No wonder that the grammar school’s first Black student was experiencing blowback from his white classmates and finding it difficult, if not impossible,

to fit in. So the last thing he needed was the attention he’d receive if Sister Aloysius were to go public with allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of Father Flynn. “He’s the only Black kid. Imagine a Black kid in the ‘60s. You’re trying to give these responses of what the nun expects, that would backfire on her, and would backfire on her son.”

to fit in. So the last thing he needed was the attention he’d receive if Sister Aloysius were to go public with allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of Father Flynn. “He’s the only Black kid. Imagine a Black kid in the ‘60s. You’re trying to give these responses of what the nun expects, that would backfire on her, and would backfire on her son.” - When Doubt made its Off Broadway premiere in 2004, the Catholic Church had only just admitted that, between 1950 and 2002, more than 10,000 children had been molested by more than 4,000 priests in the U.S.

- The 2004 play was subsequently made into a movie starring Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Viola Davis, and Amy Adams, each nominated for Oscars for their performances.

- Shanley told Vulture that he was influenced to write the play in part by the discovery that a teacher from his own Catholic school had been a serial abuser.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.