George Mitchell

Genre: portraits of blues musicians

Media: black and white

Website: none

Facebook: none

Blues Photography

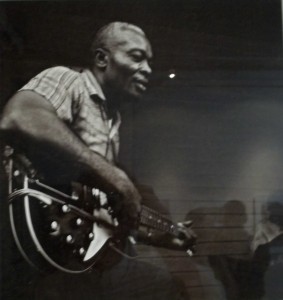

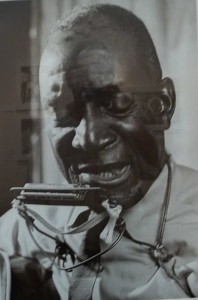

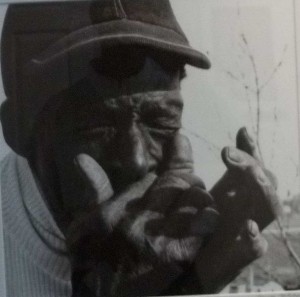

Mitchell spent nearly two decades locating, interviewing, recording, photographing and writing about some of the most popular, albeit sometimes obscure, blues musicians of the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s – names like Blues Hall-of-Famer Eugene “Buddy” Moss (left), Lonzie Thomas (who Mitchell drove into a ditch), R.L. Burnside (who Mitchell found on a tractor cutting corn), Frank Edwards (lower right, whose career spanned nine decades and who died at age 93 while on his way home from a recording session with Tim Duffy in Greenville, South Carolina), Cecil Barfield (who would not let Mitchell photograph him because he was afraid someone would turn the photo face down and stick pins in it), and the legendary Will Shade, founder and songwriter for the Memphis Jug Band.

Mitchell spent nearly two decades locating, interviewing, recording, photographing and writing about some of the most popular, albeit sometimes obscure, blues musicians of the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s – names like Blues Hall-of-Famer Eugene “Buddy” Moss (left), Lonzie Thomas (who Mitchell drove into a ditch), R.L. Burnside (who Mitchell found on a tractor cutting corn), Frank Edwards (lower right, whose career spanned nine decades and who died at age 93 while on his way home from a recording session with Tim Duffy in Greenville, South Carolina), Cecil Barfield (who would not let Mitchell photograph him because he was afraid someone would turn the photo face down and stick pins in it), and the legendary Will Shade, founder and songwriter for the Memphis Jug Band.

It started in earnest during the summer of 1967, when Mitchell borrowed a 35mm camera from the University of Minnesota and traveled with his wife, Cathy, and a Wollensack tape recorder to document blues musicians in Mississippi. After returning to Minnesota, Mitchell turned the trip into a master’s thesis that also became his first book in 1971, Blow My Blues Away. They had recorded legends Fred McDowell and Houston Stackhouse, and at the time unknowns R.L. Burnside and Othar Turner.

It started in earnest during the summer of 1967, when Mitchell borrowed a 35mm camera from the University of Minnesota and traveled with his wife, Cathy, and a Wollensack tape recorder to document blues musicians in Mississippi. After returning to Minnesota, Mitchell turned the trip into a master’s thesis that also became his first book in 1971, Blow My Blues Away. They had recorded legends Fred McDowell and Houston Stackhouse, and at the time unknowns R.L. Burnside and Othar Turner.

In the late ’60s and early 1970s, Mitchell worked as a reporter in Columbus, Georgia. Under the tutelage of the photographers at the Columbus Ledger, he shot the photographs that appeared with his stories. At the Columbus Times, he was a reporter, a photographer, and later executive editor. During that period, he produced his second book of photographs and text, I’m Somebody Inportant.

In the late ’60s and early 1970s, Mitchell worked as a reporter in Columbus, Georgia. Under the tutelage of the photographers at the Columbus Ledger, he shot the photographs that appeared with his stories. At the Columbus Times, he was a reporter, a photographer, and later executive editor. During that period, he produced his second book of photographs and text, I’m Somebody Inportant.

Mitchell then decided to become a photography teacher, and returned to the University of Minnesota where he studied photography, teaching in both the journalism and art departments. He taught photography in Atlanta at four high schools for a total of 25 years. During this time, he also authored five more books of photographs and interviews, and went on to record and photograph blues musicians throughout Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee both on his own and as a field researcher for the Columbus Museum of Art and on behalf of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs during the time he oversaw the Georgia Grassroots Music Festival.

Mitchell then decided to become a photography teacher, and returned to the University of Minnesota where he studied photography, teaching in both the journalism and art departments. He taught photography in Atlanta at four high schools for a total of 25 years. During this time, he also authored five more books of photographs and interviews, and went on to record and photograph blues musicians throughout Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee both on his own and as a field researcher for the Columbus Museum of Art and on behalf of the Bureau of Cultural Affairs during the time he oversaw the Georgia Grassroots Music Festival.

Mitchell’s photographs can be found in the permanent collections of the Columbus Museum of Art and museums in Sacramento, California and Utrecht, Holland. Over the years, at least 100 LP’s, EP’s, and CD’s of George’s blues field recordings have received critical acclaim, the most recent being The George Mitchell Collection, which includes a boxed set, available on the Fat Possum label.

Mitchell’s photographs can be found in the permanent collections of the Columbus Museum of Art and museums in Sacramento, California and Utrecht, Holland. Over the years, at least 100 LP’s, EP’s, and CD’s of George’s blues field recordings have received critical acclaim, the most recent being The George Mitchell Collection, which includes a boxed set, available on the Fat Possum label.

His Music

One of Shade’s instruments was the oil can bass, and he taught Mitchell to play. Today, Mitchell is one of the most experienced professional oil can bassists in the country, and he proudly carries on the tradition that Shade started more than 50 years ago. Mitchell first demonstrated his prowess on the oil can bass to area blues lovers during Fort Myers Music Walk on April 16th, when he performed with Frank Greathouse and Paul LaRonde (of Screamin’ & Cryin’) outside In One Instant Gallery of Photography, which was presenting Mitchell’s blues photographs and field recordings. The crowd grew so large, it virtually blocked off Jackson Street to vehicular traffic.

One of Shade’s instruments was the oil can bass, and he taught Mitchell to play. Today, Mitchell is one of the most experienced professional oil can bassists in the country, and he proudly carries on the tradition that Shade started more than 50 years ago. Mitchell first demonstrated his prowess on the oil can bass to area blues lovers during Fort Myers Music Walk on April 16th, when he performed with Frank Greathouse and Paul LaRonde (of Screamin’ & Cryin’) outside In One Instant Gallery of Photography, which was presenting Mitchell’s blues photographs and field recordings. The crowd grew so large, it virtually blocked off Jackson Street to vehicular traffic.

Mitchell reprised his performance in November of 2011 outside Arts for ACT Gallery in the River District.

Mitchell reprised his performance in November of 2011 outside Arts for ACT Gallery in the River District.

Before moving to Fort Myers, the former Atlantan played with Georgia-based blues stalwart Mudcat and the Piedmont Playboys, a quartet that specialized in traditional country blues from Georgia, Florida, Mississippi and the Carolinas. The group first began playing together at a weekly gig in Atlanta that lasted more than five years. George, Mudcat and the Piedmont Playboys (washboard player and percussionist Dan Francis and Atlanta harp player Hobo Reid) reunited on Friday, January 20, 2012 at the world-famous Buckingham Blues Bar in Fort Myers. The reunion allowed these talented, proficient musicians to share their passion and love of traditional raw southern blues with a new audience.

His Books

Dating back to 1971, Mitchell has published seven books of photographs, most with text as well. These titles include Blow My Blues Away (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971; New York: DaCapo Press, 1984); I’m Somebody Important: Young Black Voices from Rural Georgia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973); Yessir, I’ve Been Here a Long Time: The Faces and Words of Americans Who Have Lived a Century (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1975); In Celebration of a Legacy (Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art, 1981; re-published 1999, distributed by University of Georgia Press);Southern Portraits (Bear Creek, AL: Bear Creek Books, 1981); Ponce de Leon: An Intimate Portrait of Atlanta’s Most Famous Avenue (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1983); and Sweet Auburn [with his students at Grady High School] (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1996).

Dating back to 1971, Mitchell has published seven books of photographs, most with text as well. These titles include Blow My Blues Away (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971; New York: DaCapo Press, 1984); I’m Somebody Important: Young Black Voices from Rural Georgia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973); Yessir, I’ve Been Here a Long Time: The Faces and Words of Americans Who Have Lived a Century (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1975); In Celebration of a Legacy (Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art, 1981; re-published 1999, distributed by University of Georgia Press);Southern Portraits (Bear Creek, AL: Bear Creek Books, 1981); Ponce de Leon: An Intimate Portrait of Atlanta’s Most Famous Avenue (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1983); and Sweet Auburn [with his students at Grady High School] (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1996).

A number of these books have been reviewed or excerpted in numerous publications, including the New York Times Book Review, McCalls, Harper’s, Saturday Review, Ms., The Village Voice, The New York Post, The Atlanta Journal, The Chicago Tribune, and DoubleTake. Ponce de Leon was made into a hit play in Atlanta in 1987, with a second run in 1991. Ponce de Leon was also on Atlanta’s local bestseller list for more than two years running.

Mitchell’s latest book is Mississippi Hill Country Blues 1967. Intimate without pandering or posturing, it provides a raw, authentic look at African-American Blues musicians, their families and their stomping grounds in the Mississippi Hill country at a time and place where Blues musicians were viewed with pride and respect for giving voice to the poverty and pervasive discrimination that southern blacks faced on a daily basis. Mitchell brought their music to the attention of the rest of the nation by locating, interviewing, photographing and ultimately recording artists such as R.L. Burnside, Jessie Mae Hemphill, Othar Turner, Ada Mae Anderson and Joe Callicott. As a result of Mitchell’s fieldwork, others discovered the region and its distinctive style of blues, transforming the lives of many of the musicians that Mitchell first recorded.

Mitchell’s ability to connect with his subjects is evident in the photos included in the book. The musicians – and their families and friends – welcomed him in their homes, at rent parties and at fife and drum picnics. They posed for portraits, and they allowed him to hang around with his cameras while they cooked supper and danced the night away. But this book is more than a collection of historic Blues photos. Running throughout is Mitchell’s recounting of his “experience of the seminal musicological odyssey. Mississippi Hill Country Blues 1967 will be available in hardcover on Amazon.com.

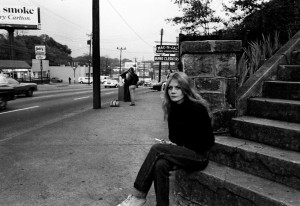

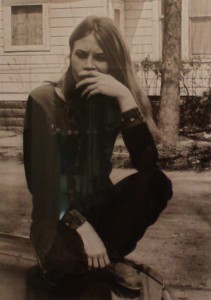

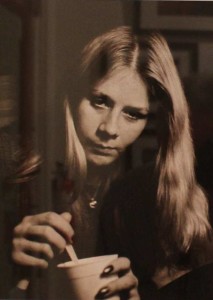

Ronda

While he is most commonly associated with his Blues photography, recordings and books, Mitchell conducted a two-year long photodocumentary that poignantly portrayed the life and struggles of a streetwalker and addict he met by happenstance in Georgia in 1985 while gathering photographs for Ponce de Leon: An Intimate Portrait of Atlanta’s Most Famous Avenue (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1983).

While he is most commonly associated with his Blues photography, recordings and books, Mitchell conducted a two-year long photodocumentary that poignantly portrayed the life and struggles of a streetwalker and addict he met by happenstance in Georgia in 1985 while gathering photographs for Ponce de Leon: An Intimate Portrait of Atlanta’s Most Famous Avenue (Atlanta: Argonne Books, 1983).

On first meeting, Ronda was merely an interesting subject he spied at the end of a day’s shooting, after he’d already stowed his cameras in the trunk of his car. But there was something about the young prostitute that inspired him to retrieve his cameras and ask her if he could snap her picture. When he studied the developed photographs, Mitchell’s professional intuition was vindicated.

”She had looked dead-square into the lens … and had revealed something of herself,” Mitchell wrote at the time. “I’m taken by the picture. Totally taken. I barely notice her face is broken out and her hair isn’t that clean.” He couldn’t see beyond the quiet desperation he saw reflected in Ronda’s sad, disturbing eyes. “Sensitive and vulnerable, they openly reveal so much disturbance. They are … haunting.”

Naturally, he had to go back to Ponce de Leon to find her. But Mitchell’s approach to his subject was unique. Rather than dispassionately photograph Rondo over a period of months, Mitchell allowed her to become a collaborator as well as subject. “She was willing to share herself with the world even though she was a practising prostitute and as hard core a junkie as you are going to find” – although ironically she objected early on to Mitchell photographing her with a cigarette because she did not want her mother to see pictures of her smoking.

Naturally, he had to go back to Ponce de Leon to find her. But Mitchell’s approach to his subject was unique. Rather than dispassionately photograph Rondo over a period of months, Mitchell allowed her to become a collaborator as well as subject. “She was willing to share herself with the world even though she was a practising prostitute and as hard core a junkie as you are going to find” – although ironically she objected early on to Mitchell photographing her with a cigarette because she did not want her mother to see pictures of her smoking.

Shot in black and white, the images in the series are mesmerizing, but the accompanying narrative that documents Mitchell’s exchanges with the girl are nothing short of spellbinding. Many of Mitchell’s shots are sandwiched between tricks. Ronda is, after all, a working girl with a drug habit to support. “You got to take these quick,” she says matter-of-factly during Mitchell’s very first shoot. “I’m losing money.” And in the unlikely setting of a neighborhood filled with ivy-covered stone walls and beautifully restored Victorian homes, she warns that “if a trick comes, I’m gone.” While Ronda is clearly on board with the expose Mitchell is lensing, tricks and drugs always take precedence.

Shot in black and white, the images in the series are mesmerizing, but the accompanying narrative that documents Mitchell’s exchanges with the girl are nothing short of spellbinding. Many of Mitchell’s shots are sandwiched between tricks. Ronda is, after all, a working girl with a drug habit to support. “You got to take these quick,” she says matter-of-factly during Mitchell’s very first shoot. “I’m losing money.” And in the unlikely setting of a neighborhood filled with ivy-covered stone walls and beautifully restored Victorian homes, she warns that “if a trick comes, I’m gone.” While Ronda is clearly on board with the expose Mitchell is lensing, tricks and drugs always take precedence.

Ronda’s unpretentious, often-stark self-assessment jumps from Mitchell’s images and accompanying narrative. “I’m the only junkie they know with a traveling photographer,” she quips when a trick wants to join in a photograph Mitchell takes of her while they are talking in a Popeye’s restaurant located near Ronda’s corner. “It will prove that everybody in this world needs someone they can love and trust… Even people like us,” she tells Mitchell, when he asks if he can interview her and her boyfriend Melvin the day after a knife-wielding trick threatened to slit Ronda’s throat. And when Mitchell tells a friend of Ronda’s that he’s doing a whole book on her, a shadow crosses her face and her gaze drops downward toward the sidewalk. “Yeah…well…,” she demurs. “I’m not too sure about what I’m representing.”

Ronda’s unpretentious, often-stark self-assessment jumps from Mitchell’s images and accompanying narrative. “I’m the only junkie they know with a traveling photographer,” she quips when a trick wants to join in a photograph Mitchell takes of her while they are talking in a Popeye’s restaurant located near Ronda’s corner. “It will prove that everybody in this world needs someone they can love and trust… Even people like us,” she tells Mitchell, when he asks if he can interview her and her boyfriend Melvin the day after a knife-wielding trick threatened to slit Ronda’s throat. And when Mitchell tells a friend of Ronda’s that he’s doing a whole book on her, a shadow crosses her face and her gaze drops downward toward the sidewalk. “Yeah…well…,” she demurs. “I’m not too sure about what I’m representing.”

Interestingly, Mitchell’s view differs drastically. When Ronda shows him a wallet identifying her by the last names of her boyfriend, ex-husband, stepfather and biological father, he regards this as

Interestingly, Mitchell’s view differs drastically. When Ronda shows him a wallet identifying her by the last names of her boyfriend, ex-husband, stepfather and biological father, he regards this as  “visual documentation of what I’ve come to see as a severe identity problem.” But Ronda knows she is an addict. It’s Mitchell who thinks that someday she’ll kick the habit and be straight. But just as Ronda as Ronda is conflicted, so is Mitchell who avows repeatedly that he does not condone her drug use just “because I’m photographing it.” More stridently, he tells her when she asks for drug money, “I’m not your drug supplier.” And even after she offers him everything in her apartment, Melvin and herself included, he replies “I’m not in the business of supporting your habit. You understand? I don’t like it!” But that doesn’t prevent him from seizing every chance Rondo gives him to shoot her shooting up … or zero in on the track marks on her arm.

“visual documentation of what I’ve come to see as a severe identity problem.” But Ronda knows she is an addict. It’s Mitchell who thinks that someday she’ll kick the habit and be straight. But just as Ronda as Ronda is conflicted, so is Mitchell who avows repeatedly that he does not condone her drug use just “because I’m photographing it.” More stridently, he tells her when she asks for drug money, “I’m not your drug supplier.” And even after she offers him everything in her apartment, Melvin and herself included, he replies “I’m not in the business of supporting your habit. You understand? I don’t like it!” But that doesn’t prevent him from seizing every chance Rondo gives him to shoot her shooting up … or zero in on the track marks on her arm.

Volume one of Street Prostitute: Photographing Ronda doesn’t end with her overdosing or being killed by a trick. Instead, it ends in Grady Hospital with Ronda’s life threatened by a skin infection from dirty needles and possibly endocarditis, an infection of the heart valve” which might require open heart surgery to replace. But while Mitchell coyly declines to reveal what ultimately happens to his subject, collaborator and by then his friend, he does perhaps foreshadow Ronda’s denouement. When her social worker and trick offers to take her away from her life of prostitution and addiction to a place he has in the mountains where she can start her life over, “she just looked at me, and she asked me: ‘Why would anybody want me?'”

Volume one of Street Prostitute: Photographing Ronda doesn’t end with her overdosing or being killed by a trick. Instead, it ends in Grady Hospital with Ronda’s life threatened by a skin infection from dirty needles and possibly endocarditis, an infection of the heart valve” which might require open heart surgery to replace. But while Mitchell coyly declines to reveal what ultimately happens to his subject, collaborator and by then his friend, he does perhaps foreshadow Ronda’s denouement. When her social worker and trick offers to take her away from her life of prostitution and addiction to a place he has in the mountains where she can start her life over, “she just looked at me, and she asked me: ‘Why would anybody want me?'”

Mitchell’s first and only exhibit of Ronda took place at Arts for ACT Gallery in the River District in May. If you missed, you can still view the collection on flickr.

Related Articles and Links.

- ‘Ronda’ shows another side of George Mitchell’s photo-documentary skills (06-30-13)

- ‘Mississippi Hill Country Blues 1967’ is George Mitchell’s eighth book (06-28-13)

- George Mitchell blues photographs on exhibit at Mississippi Museum of Art (06-28-13)

- George Mitchell ‘Ronda at Eye Level’ exhibit at ACT will touch your heartstrings (05-03-13)

- George Mitchell joins Belmont & Jones at French Connection for Music Walk (01-14-13)

- Profile on photographer and author George Mitchell (01-19-12)

- Arts for ACT to showcase Blues art of Lennie Jones & George Mitchell in February (01-17-12)

- Blues photog George Mitchell to perform with Mudcat at Buckingham Blues Bar (01-17-12)

- Rachael Scott gives George Mitchell lessons in TtV photography during Art Walk (05-08-11)

- Oil can bassist George Mitchell wowed Music Walkers at In One Instant last night (04-17-11)

- George Mitchell drove blind blues musician Lonzie Thomas into a ditch (04-11-11)

- Documentarian George Mitchell found R.L. Burnside on a tractor cutting corn (04-10-11)

- George Mitchell promotes photo exhibit and Music Walk on Florida Gulf Coast Live (04-09-11)

- Blues documentarian George Mitchell profiles Frank Edwards at In One Instant (04-05-11)

- Blues anthology photographs now on exhibit at In One Instant Gallery (04-04-11)

- Reminder about Mitchell blues exhibition at In One Instant Gallery this Friday (03-28-11)

- George Mitchell captured blues history on film and on tape (03-22-11)

- In One Instant Gallery and George Mitchell offer patrons piece of blues history (03-21-11)

- In One Instant Gallery’s George Mitchell recalls photos he didn’t take (03-20-11)

- Will Shade started George Mitchell in blues photography, recording and music (03-19-11)

- More on In One Instant Gallery’s blues documentarian George Mitchell (03-18-11)

- Spotlight on blues photographer and musician George Mitchell (03-17-11)

- Blues documentarian George Mitchell exhibits at In One Instant Gallery in April (03-16-11)

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

What happened to Ronda? Please tell me that she finally found peace and a happy life.