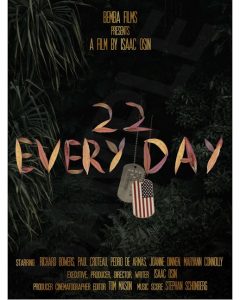

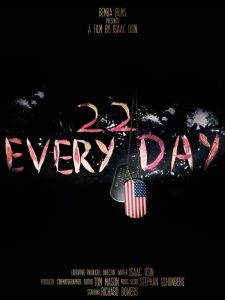

Isaac Osin short film, ’22 Every Day,’ portrays a day in the life of a combat vet coping with PTSD

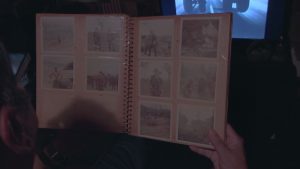

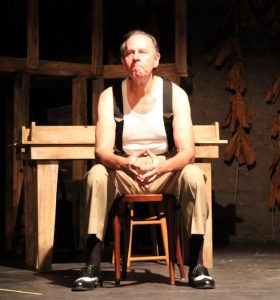

One of the short films that will be screened during this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival is Isaac Osin’s 22 Every Day. The movie follows a military combat veteran as he goes about his daily routine, showing how he relives his experiences during the war years later.

One of the short films that will be screened during this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival is Isaac Osin’s 22 Every Day. The movie follows a military combat veteran as he goes about his daily routine, showing how he relives his experiences during the war years later.

With the war in Afghanistan coming to end this Fall, there is renewed interest in how a new generation of combat veterans will deal with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in the aftermath of 20 years of armed conflict. But tens of thousands of Vietnam combat vets are still grappling with PTSD nearly half a century after that war ended.

“My  experience as an infantry soldier in the Vietnam War is one of the reasons I was motivated to make this film,” Osin acknowledges. “Having witnessed PTSD first hand and that of fellow veterans, I felt that people might better understand PTSD if I could make a movie that puts them into the mindset of someone suffering from it.”

experience as an infantry soldier in the Vietnam War is one of the reasons I was motivated to make this film,” Osin acknowledges. “Having witnessed PTSD first hand and that of fellow veterans, I felt that people might better understand PTSD if I could make a movie that puts them into the mindset of someone suffering from it.”

There have been numerous studies of PTSD in Vietnam veterans. The seminal study was conducted by the U.S. Government following a Congressional mandate issued in 1983. Known as the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS), it found that 30 percent of male and 27 percent of female combat  veterans had PTSD at some point following their tour in Vietnam. At the time of the study, 15 percent of the men and 9 percent of the women were still complaining of PTSD symptoms.

veterans had PTSD at some point following their tour in Vietnam. At the time of the study, 15 percent of the men and 9 percent of the women were still complaining of PTSD symptoms.

Those percentages barely dissipated 14 years later when Harvard School of Public Health, Columbia University, The American Legion, and  the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center did a follow-up study. At that time, 11 percent of Vietnam combat vets were still coping with PTSD.

the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center did a follow-up study. At that time, 11 percent of Vietnam combat vets were still coping with PTSD.

Vietnam vets who continued to have PTSD experienced  considerably more psychological and social problems, reported lower satisfaction with their marriages, sex lives and lives in general, and had higher divorce rates and more physical maladies (ranging from aches, colds and fatigue to heart disease and other degenerative disorders).

considerably more psychological and social problems, reported lower satisfaction with their marriages, sex lives and lives in general, and had higher divorce rates and more physical maladies (ranging from aches, colds and fatigue to heart disease and other degenerative disorders).

Half of all people  with PTSD experience clinical depression at some point in time. In an effort to self-medicate their depression and chronic pain (PTSD is associated with higher incidents of arthritis and digestive tract disorders such as GERD and peptic ulcers), many vets with PTSD develop alcohol and drug

with PTSD experience clinical depression at some point in time. In an effort to self-medicate their depression and chronic pain (PTSD is associated with higher incidents of arthritis and digestive tract disorders such as GERD and peptic ulcers), many vets with PTSD develop alcohol and drug  dependency or addiction.

dependency or addiction.

PTSD has also been found to be a risk factor for heart disease and diabetes.

And for those vets suffering from PTSD who are not living alone, their partners and children are also affected by the disorder.

But even for combat veterans  who have been suffering from PTSD for many years (or experience late onset PTSD), recovery can still occur.

who have been suffering from PTSD for many years (or experience late onset PTSD), recovery can still occur.

But only with treatment.

“One of the reasons I made this film is in the hope that someone in the audience might follow the main character, understand  his frame of mind, relate to this story, and ask for help,” Osin remarks optimistically.

his frame of mind, relate to this story, and ask for help,” Osin remarks optimistically.

Osin meets regularly with veterans, both in support groups and other gatherings. While he’s concerned, even alarmed by then number of Afghan war veterans who won’t come to meetings or get treatment, he understands their reticence.

“For me, many years passed before I realized that I had [PTSD],” Isaac relates. “It wasn’t until my regular doctor told me  that the way I think was not right and that I needed to consult with a professional that I realized I had a problem. I wasn’t happy about it, but I finally accepted that I did need help. And it probably saved my life because you don’t know what you’re going to do when you find yourself in certain situations.”

that the way I think was not right and that I needed to consult with a professional that I realized I had a problem. I wasn’t happy about it, but I finally accepted that I did need help. And it probably saved my life because you don’t know what you’re going to do when you find yourself in certain situations.”

Veterans are 1.5 times more likely to die by suicide than Americans who never served in the military. For female veterans, the risk factor is 2.2 times more likely. In fact, the film takes its title from a 2013 report conducted by the Department  of Veteran Affairs which estimated that 22 vets die by suicide each and every day.

of Veteran Affairs which estimated that 22 vets die by suicide each and every day.

In the last four years, the official government estimate on the number of veterans who die by suicide has gone from 22 a day to 17 a day. But the rate of suicides among veterans didn’t decrease over that span. Only the way the figures are sorted and presented did.

But even that’s misleading.

The total number of  suicides among veterans has increased four of the last five years on record. From 2007 to 2017, the rate of suicide among veterans jumped almost 50 percent. During the 13 year span beginning in 2005 and ending with 2017 (the latest year for which there exists data), nearly 80,000 vets took their own lives. And the solution is not merely a matter of marshalling more resources to the V.A. Nearly two-thirds of those suicides are among veterans not using V.A. health services.

suicides among veterans has increased four of the last five years on record. From 2007 to 2017, the rate of suicide among veterans jumped almost 50 percent. During the 13 year span beginning in 2005 and ending with 2017 (the latest year for which there exists data), nearly 80,000 vets took their own lives. And the solution is not merely a matter of marshalling more resources to the V.A. Nearly two-thirds of those suicides are among veterans not using V.A. health services.

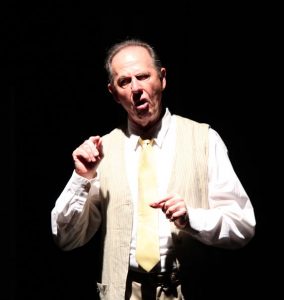

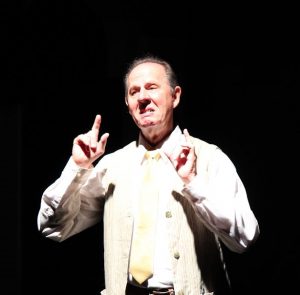

When Osin began working on the film, he and his cast (Richard Bowers,  Paul Croteau and Pedro De Armas are all ex-military) were exclusively focused on making a film they could share with veteran’s organizations in order to reach disaffected combat veterans and at-risk active military personnel.

Paul Croteau and Pedro De Armas are all ex-military) were exclusively focused on making a film they could share with veteran’s organizations in order to reach disaffected combat veterans and at-risk active military personnel.

“But the cinematographer [Tom Mason] did such a wonderful job, that [my friends at UFTA] said you should enter it into a film festival,” chuckles Osin, who learned just moments before that 22 Every Day had been juried into Bonita Springs International Film Festival.

22 Every Day will actually screen twice during this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival.

It  is part of Local Shorts Block 1 that begins at noon on Saturday, Mary 15 in the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center (along with Jeff Frey’s Every Second Counts, Prometheus Bound by Maddalena Kingsley, The Knife by Karen Whitaker and J. Bert Davis, and Waiting for Me by Glendalina Ziemba). And it will be shown a second time at the Laboratory Theater of Florida at 3:00 p.m. on Sunday, May 16.

is part of Local Shorts Block 1 that begins at noon on Saturday, Mary 15 in the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center (along with Jeff Frey’s Every Second Counts, Prometheus Bound by Maddalena Kingsley, The Knife by Karen Whitaker and J. Bert Davis, and Waiting for Me by Glendalina Ziemba). And it will be shown a second time at the Laboratory Theater of Florida at 3:00 p.m. on Sunday, May 16.

April 16, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.