‘Radical Jew’ stirs controversy at January 2 T.G.I.M.

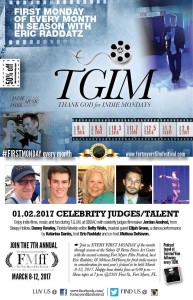

During T.G.I.M. this past Monday night, hosts Eric Raddatz and Melissa DeHaven screened a documentary titled The Radical Jew. While many of the films screened during Thank God for Indie Mondays have never been seen before, this film has already been juried into and shown at the Charlotte Film Festival (where it won Best Short Documentary), Tallgrass Film Festival (where it won the Golden Strands Award for outstanding short documentary), DocUtah International Film Fest, Warsaw Jewish Film Fest, Society for Visual Anthropology

During T.G.I.M. this past Monday night, hosts Eric Raddatz and Melissa DeHaven screened a documentary titled The Radical Jew. While many of the films screened during Thank God for Indie Mondays have never been seen before, this film has already been juried into and shown at the Charlotte Film Festival (where it won Best Short Documentary), Tallgrass Film Festival (where it won the Golden Strands Award for outstanding short documentary), DocUtah International Film Fest, Warsaw Jewish Film Fest, Society for Visual Anthropology  Film Fest, Covellite International Film Fest, Director’s Circle Festival of Shorts and the Congregation Anshe Sholom Bnai Israel.

Film Fest, Covellite International Film Fest, Director’s Circle Festival of Shorts and the Congregation Anshe Sholom Bnai Israel.

The film follows an American-born Israeli by the name of Baruch Marzel. He was the leader of a far-right political group known as Kach, which Israel banned in 1995 as a terrorist organization. Marzel is an ideologue, and he learned the dogma he espouses today from Kach party founder, Meir Kahane. A rabbi, Kahane started the Jewish  Defense League in New York City in the 1960s before moving to Israel in 1971 and winning a seat in the Israeli Parliament in 1984. Among the legislation that he proposed were laws banning marriage between Jews and Arabs and creating segregated beaches.

Defense League in New York City in the 1960s before moving to Israel in 1971 and winning a seat in the Israeli Parliament in 1984. Among the legislation that he proposed were laws banning marriage between Jews and Arabs and creating segregated beaches.

When filmmaker Noam Osband questioned Marzel about the similarity between those proposals and Hitler’s 1935 Nuremberg Laws, which prohibited and invalidated marriage between Jews and Germans  and criminalized extramarital relations between Jews and German citizens, he flatly replied that he does not hate Arabs because they’re Arabs, but because “they are our enemy.”

and criminalized extramarital relations between Jews and German citizens, he flatly replied that he does not hate Arabs because they’re Arabs, but because “they are our enemy.”

In their comments to the audience, the T.G.I.M. panel of judges were troubled by the film’s one-sided  treatment of the Israeli-Palestine conflict. In fact, indie filmmaker Jordan Axelrod stated that “when you’re making a documentary, it’s important to show both sides.” While actor Danny Rawley liked the film’s straightforward approach, he questioned whether the subject matter would have broad enough appeal among viewers to be included in a film festival at all.

treatment of the Israeli-Palestine conflict. In fact, indie filmmaker Jordan Axelrod stated that “when you’re making a documentary, it’s important to show both sides.” While actor Danny Rawley liked the film’s straightforward approach, he questioned whether the subject matter would have broad enough appeal among viewers to be included in a film festival at all.

These sentiments were echoed by a number of members of the  T.G.I.M. audience. A woman of Irish-American descent, saw similarities between what’s happening in the Palestine settlements on the Gaza Strip and The Troubles that embroiled Northern Ireland and The Irish Republic between the late 1960s and the Good Friday Belfast Agreement of 1998. “This summer I’m bringing my grandchildren to Ireland and to Northern Ireland because, I’m happy to say, finally we have peace,”

T.G.I.M. audience. A woman of Irish-American descent, saw similarities between what’s happening in the Palestine settlements on the Gaza Strip and The Troubles that embroiled Northern Ireland and The Irish Republic between the late 1960s and the Good Friday Belfast Agreement of 1998. “This summer I’m bringing my grandchildren to Ireland and to Northern Ireland because, I’m happy to say, finally we have peace,”  she shared. “I look at this and think, my God, he’s there with his grandchildren! They need peace. Other people have found a way [to establish peace]. This touched me because I’m a grandmother.”

she shared. “I look at this and think, my God, he’s there with his grandchildren! They need peace. Other people have found a way [to establish peace]. This touched me because I’m a grandmother.”

A number of audience members shared this view. “It was a good powerful film, but I kept thinking of John Lennon and ‘give peace a chance’,” said one man. “Yoko Ono. Imagine Peace,” added another.

The prospects for peace seemed unrealistic to several in Monday night’s T.G.I.M. crowd. “When you believe in what you want, there’s  no stopping you,” said one man soberly.

no stopping you,” said one man soberly.

But all of these concerns missed the true thrust of the film. “The Radical Jew isn’t about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it’s a film about extremism,” notes the filmmaker, who is quick to add that extremists come in all shades and stripes. Viewed from that perspective, the film has universal application. Muslim extremists and White Supremacists would sound just like Baruch Marzel because they see the world in terms of us versus them.

And a major point underlying this depiction is to show that even the most radical and ruthless extremists are often devoted parents and loving spouses, something that many T.G.I.M. audience members found abhorrent.

And a major point underlying this depiction is to show that even the most radical and ruthless extremists are often devoted parents and loving spouses, something that many T.G.I.M. audience members found abhorrent.

For example, one woman was particularly repelled by a moment in the film in which Marzel speaks graphically about seven Syrian commandos he killed in Lebanon (including three unarmed men he’d taken as prisoners) that was followed by a scene in which he dances with his grandchildren, slipping pink pieces of cotton candy  into their mouths.

into their mouths.

“[The filmmaker] is trying to portray this extreme person who kills people as a good man,” she protested.” That disturbed me. No. He is a killer.”

Others were similarly conflicted about the filmmaker’s perceived effort to humanize such an extremist. But in his efforts to humanize Baruch Marzel, which included the use (perhaps even overuse) of sympathy-inducing and empathy-provoking close-up footage, filmmaker Noam Osband brought into  focus the deeper, even more troubling disconnect that often exists between a person’s political ideology and religious views and their family life.

focus the deeper, even more troubling disconnect that often exists between a person’s political ideology and religious views and their family life.

“When we encounter people with views that are strong and that we might not agree with, we’re unnerved by thinking about them being human beings, too,” says Osband.

It’s a phenomenon known as the Eichmann/Stangl paradox.

It’s a phenomenon known as the Eichmann/Stangl paradox.

“From Eichmann [who was the mastermind of the German’s “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” that resulted in the extermination of 6 million Jews] and Stangl [the commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps] on down, 90 percent of [the Nazis who ran and staffed the death camps] – sometimes before the war and certainly after the war – were solid family men and women, devoted to their children, loyal to their relatives, hard-working, tax-paying good citizens  and good neighbors who did their duty, tended their gardens and seldom made trouble for anyone,” notes Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. “But when they put on the uniform, they became something else: monsters, sadists, torturers, killers, desk murderers. The minute they took off the uniform, they became model citizens again.

and good neighbors who did their duty, tended their gardens and seldom made trouble for anyone,” notes Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. “But when they put on the uniform, they became something else: monsters, sadists, torturers, killers, desk murderers. The minute they took off the uniform, they became model citizens again.

Adolf Eichmann’s wife could never envision or accept that the  man she loved and shared her life with could orchestrate the murder of six million men, women and children.

man she loved and shared her life with could orchestrate the murder of six million men, women and children.

Theresa Stangl refused to accept the reality of her husband’s deeds during World War II. “Never, never did he strike or spank the children,” she argued. “He was an incredibly good and kind father. He played with the children by the hour. He made them dolls,  helped them dress them up. He worked with them; taught them innumerable things. They adored him – all three of them. He was sacred to them.” And yet, more than one million prisoners died under his command at Sobibor and Treblinka.

helped them dress them up. He worked with them; taught them innumerable things. They adored him – all three of them. He was sacred to them.” And yet, more than one million prisoners died under his command at Sobibor and Treblinka.

Wiesenthal never solved the Eichmann/Stangl paradox. Nor did Stangl biographer Gitta Sereny, who wrote Into that Darkness: An Examination of Conscience. Which is why films like The Radical Jew are still important in 2017. The point is not to humanize extremists like Baruch Mazel, but to understand and appreciate the  fact that even though someone may be a loving father and grandfather, he nevertheless has the ability to perform horrific acts in furtherance of political ideology, religious belief or duty to some higher authority who does all the thinking and demands blind allegiance from his followers.

fact that even though someone may be a loving father and grandfather, he nevertheless has the ability to perform horrific acts in furtherance of political ideology, religious belief or duty to some higher authority who does all the thinking and demands blind allegiance from his followers.

“The film showed a man with extreme political  views but at the same time who is a human being,” acknowledged one audience member. “But it would have been more useful it [the filmmaker] had included Palestinians who had the same sort of attributes, or left-wing Israelis. It would have given the film broader context.”

views but at the same time who is a human being,” acknowledged one audience member. “But it would have been more useful it [the filmmaker] had included Palestinians who had the same sort of attributes, or left-wing Israelis. It would have given the film broader context.”

Perhaps, but The Radical Jew makes the point even in isolation.

“We’re all subject to outside influences that make us who we are,” noted someone else. “And hopefully we can grow beyond the hatred.”

“We’re all subject to outside influences that make us who we are,” noted someone else. “And hopefully we can grow beyond the hatred.”

But how, as a society, do we accomplish such a lofty goal? Is it even possible to prevent seemingly good and decent people from becoming radicalized? Is it feasible in any day and age for people to assume responsibility for their own thoughts and belief structure rather than allow autocrats and demagogues to think for them?

“That’s why it is important to show a film like The Radical Jew,” Eric Raddatz summed up when the audience participation segment of the evening finally drew to a close. “How else and where else will we have the opportunity to have a conversation such as this?”

And that’s one reason that Thank God for Indie Mondays is also known about town as “Intellectualization Mondays.”

If you were not at T.G.I.M. this past Monday, you may yet get to see The Radical Jew. Sounds like from all the buzz following the screening that the documentary will be part of the 7th Annual Fort Myers Film Festival.  It runs from March 8-12, 2017.

It runs from March 8-12, 2017.

January 4, 2017.

Related Posts:

- Dialogue is the keynote of Thank God for Indie Mondays

- Season Seven (2016-2017) T.G.I.M. Schedule

- January, 2017 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Jordan Axelrod

- January, 2017 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Danny Rawley

- January, 2017 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Betty Wells

- January, 2017 T.G.I.M. musical guest Elijah Green

- January, 2017 T.G.I.M. dance performer Katarina Danks

Fort Myers Film Festival screens local film, ‘Three Wishes,’ at T.G.I.M.

Fort Myers Film Festival screens local film, ‘Three Wishes,’ at T.G.I.M.- ‘Consent’ big hit with December, 2016 judges and T.G.I.M. audience

- World premiere of ‘Bubbles’ horrifies audience and scares T.G.I.M. judges

- Multi-disciplinary artist Cesar Aguilera ventures into film at November’s T.G.I.M.

- December, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Gina Birch

November, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Toni Gonzales

November, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Toni Gonzales- November, 2016 T.G.I.M. musical guest Abby Fletcher

- At Monday night’s T.G.I.M., a stand-up comedy act broke out

- October, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge Stephanie Davis

October, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge, filmmaker John Scoular

October, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge, filmmaker John Scoular- October, 2016 T.G.I.M. celebrity judge, Florida Rep actor Jason Parrish

- October, 2016 T.G.I.M. musical guest Al Holland

- September TGIM celebrity judge Jason Maughan

- September TGIM celebrity judge Dan Miller

- Recap of September’s T.G.I.M. screenings

- September T.G.I.M. singer, songwriter and celebrity judge Julia DeTomaso

- August TGIM celebrity judge Kaycie Lee

- August TGIM celebrity judge Justin Verely

- Recap of August’s T.G.I.M. screenings

- August T.G.I.M. entertainer, singer-songwriter Gabrielle MacAfee

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.