Where There Is Darkness

Where There is Darkness was named by the Fort Myers Film Festival as Best Documentary. The feature-length documentary has been accepted into more than 40 film festivals since being completed last year and has won more than 30 awards.

Where There is Darkness was named by the Fort Myers Film Festival as Best Documentary. The feature-length documentary has been accepted into more than 40 film festivals since being completed last year and has won more than 30 awards.

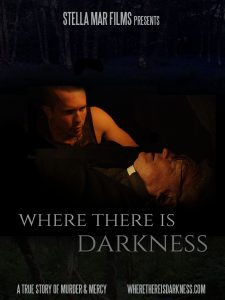

The film was made by Orlando-based production company Stella Mar Films. Filmmaker Sean Bloomfield used an imaginative mix of actual footage, eyewitness interviews and staged re-enactments  to tell the story of the nationwide search for Fr. Rene Robert, a beloved priest who went missing from St. Augustine, Florida in 2016, detail the apprehension, incarceration and sentencing of the 28-year-old man who abducted and killed the priest, and draw attention to the complex psychological factors that led him to murder the very man who had so assiduously tried to help him.

to tell the story of the nationwide search for Fr. Rene Robert, a beloved priest who went missing from St. Augustine, Florida in 2016, detail the apprehension, incarceration and sentencing of the 28-year-old man who abducted and killed the priest, and draw attention to the complex psychological factors that led him to murder the very man who had so assiduously tried to help him.

Although audiences in the northeastern Florida and Georgia are familiar with the story through contemporaneous real time television reports and newspaper accounts of the priest’s disappearance and the manhunt for his abductor, even viewers completely unfamiliar with the story quickly gain an intimate feel for Father Rene from descriptions, recollections and anecdotes furnished by his family, friends, parishioners and many others whose life Father Rene touched. But Bloomfield counterbalances these endearing and often humorous reminisces with cut-aways

Although audiences in the northeastern Florida and Georgia are familiar with the story through contemporaneous real time television reports and newspaper accounts of the priest’s disappearance and the manhunt for his abductor, even viewers completely unfamiliar with the story quickly gain an intimate feel for Father Rene from descriptions, recollections and anecdotes furnished by his family, friends, parishioners and many others whose life Father Rene touched. But Bloomfield counterbalances these endearing and often humorous reminisces with cut-aways  to news anchors and field correspondents reporting on efforts to locate Father Rene and the growing sense of dread shared by the priest’s family and friends and the community, at large.

to news anchors and field correspondents reporting on efforts to locate Father Rene and the growing sense of dread shared by the priest’s family and friends and the community, at large.

What emerges from this tension-packed narrative is the picture of a humble, unassuming, nonjudgmental man of the cloth dedicated to reaching out to people who were ill, downtrodden and generally incapable of helping themselves – often using his own meager income and retirement savings to  provide financial assistance to those less fortunate than he. While laudable, even saintly, Father Rene was humanly flawed and richly idiosyncratic. He religiously donned a New York Yankees ballcap no matter where he went, much to the chagrin of his superiors in the church and those of his family and friends who had the misfortune of being Boston Red Sox fans. He had an almost unreasonable affinity

provide financial assistance to those less fortunate than he. While laudable, even saintly, Father Rene was humanly flawed and richly idiosyncratic. He religiously donned a New York Yankees ballcap no matter where he went, much to the chagrin of his superiors in the church and those of his family and friends who had the misfortune of being Boston Red Sox fans. He had an almost unreasonable affinity  for sandals, thought that cheese could improve any food group, and was almost obsessive-compulsive when it came to recycling. Rather than distracting from the documentary’s plotline and underlying message, mention of these quirks and foibles sagely served to augment and cement the audience’s investment in the priest’s ultimate fate – and that of his abductor and eventual murderer.

for sandals, thought that cheese could improve any food group, and was almost obsessive-compulsive when it came to recycling. Rather than distracting from the documentary’s plotline and underlying message, mention of these quirks and foibles sagely served to augment and cement the audience’s investment in the priest’s ultimate fate – and that of his abductor and eventual murderer.

“My co-filmmakers and I were drawn to this story because we saw that it could be told in a way that challenges audiences in positive ways, just as it challenged us as  filmmakers,” Bloomfield notes. “On the surface, Where There Is Darkness is a true crime documentary, but, beneath all the suspense and mystery, there are so many deeper layers.”

filmmakers,” Bloomfield notes. “On the surface, Where There Is Darkness is a true crime documentary, but, beneath all the suspense and mystery, there are so many deeper layers.”

Many of those deeper layers involved an examination of the perpetrator, Steven Murray, and his family. Steven’s father was physically and emotionally abusive to his son and two daughters, Bobbie Jean and Crystal. Further, he sexually assaulted all three children. Although she was aware of the physical and sexual abuse, their mother did nothing to intervene. Not surprisingly, all three children suffered both as teens and  adults from low self-esteem, depression and drug addiction. But only Steven became violent.

adults from low self-esteem, depression and drug addiction. But only Steven became violent.

Echoing Father Rene’s nonjudgmental demeanor, Bloomfield and his colleagues at Stella Mar Films portrayed Steven’s backstory, and that of his sisters, in a fair, even-handed and nonjudgmental way. Shining brightly through the  dark shadows cast by their severely dysfunctional early family life, in particular, are the sisters’ compassion and unwavering love, both for the father who abused them and their brother, in spite of his heinous crime.

dark shadows cast by their severely dysfunctional early family life, in particular, are the sisters’ compassion and unwavering love, both for the father who abused them and their brother, in spite of his heinous crime.

The documentary also captures the commitment and dedication of the detectives who were assigned to the case in the days following Father Rene’s disappearance, and the pivotal role they played in helping both families meet and heal in the aftermath of the murder and Steven’s conviction and sentencing

“I  loved getting to know a different side of law enforcement that you don’t normally see,” Bloomfield told the Fort Myers Film Festival audience that saw the film during the ensuing Q&A. “Those detectives are amazing. They keep in touch with the victims’ families in all their cases and they keep in touch with the perpetrators’ families too. They carry so, so much weight, such an emotional burden. I really came to admire them and the work they do.”

loved getting to know a different side of law enforcement that you don’t normally see,” Bloomfield told the Fort Myers Film Festival audience that saw the film during the ensuing Q&A. “Those detectives are amazing. They keep in touch with the victims’ families in all their cases and they keep in touch with the perpetrators’ families too. They carry so, so much weight, such an emotional burden. I really came to admire them and the work they do.”

The local sheriff’s office in St. Augustine was instrumental in making the film possible. From the outset, Sheriff David Shoar (who’d been one of Father Rene’s longtime friends) opened his case files to Bloomfield and his colleagues, and even put them in touch with Bobbie Jean and Crystal so that they could get their side of the story.

The local sheriff’s office in St. Augustine was instrumental in making the film possible. From the outset, Sheriff David Shoar (who’d been one of Father Rene’s longtime friends) opened his case files to Bloomfield and his colleagues, and even put them in touch with Bobbie Jean and Crystal so that they could get their side of the story.

The Sheriff did more than merely open his files. He made other resources available for the reenactments that Bloomfield and his team staged to illustrate key stages in the story  of Father Rene’s kidnapping and murder. For example, the documentary includes a chase scene that was filmed at the Sheriff Department’s test track for safety purposes.

of Father Rene’s kidnapping and murder. For example, the documentary includes a chase scene that was filmed at the Sheriff Department’s test track for safety purposes.

“It was amazing,” Bloomfield observes. “They really trusted us to make this film.”

While the story took numerous twists and turns, the biggest  was the revelation after Steven’s apprehension of a prescient declaration that Father Rene’ had written 20 years prior to his death that if he were ever murdered, he did not want the perpetrator to be subjected to the death penalty no matter how egregious the crime or how much he may have suffered. Although not legally binding, the court chose to honor that declaration, sentencing Steven to life without the possibility of parole.

was the revelation after Steven’s apprehension of a prescient declaration that Father Rene’ had written 20 years prior to his death that if he were ever murdered, he did not want the perpetrator to be subjected to the death penalty no matter how egregious the crime or how much he may have suffered. Although not legally binding, the court chose to honor that declaration, sentencing Steven to life without the possibility of parole.

“His life in prison is not going to be easy. He’s already been stabbed a few times,” Sean discloses.

Indeed.

While it  was difficult enough to locate and obtain the rights to news footage, conduct interviews and stage reenactments, the task of editing all the material the filmmakers accumulated proved even more daunting.

was difficult enough to locate and obtain the rights to news footage, conduct interviews and stage reenactments, the task of editing all the material the filmmakers accumulated proved even more daunting.

“We had enough footage to make a ten-part series,” Bloomfield quipped during the Q&A.

But they culled their footage and distilled all their research into a tight 103-minute feature that never drags. In fact, many viewers have described Where There Is Darkness as “compelling,” “riveting” and “impactful.”

“We  tried to make the documentary a rollercoaster of emotion, with lots of ups and downs with some humor mixed in,” Bloomfield shared.

tried to make the documentary a rollercoaster of emotion, with lots of ups and downs with some humor mixed in,” Bloomfield shared.

But perhaps the best gauge of the film’s success was the reception it received when Bloomfield and Stella Mar Films screened the documentary in St. Augustine.

“All of Father Rene’s family and friends came. The detectives and the sheriffs also came. The priests and Steven’s sisters came as well,” Bloomfield recounts. “We were nervous, but we felt good about what we got in there. To see Father Rene’s sisters and Steven’s sisters hugging and crying  together after the screening made us feel like we did our job well. Even the detectives got in the hug.”

together after the screening made us feel like we did our job well. Even the detectives got in the hug.”

Today, there is reason for hope. Bobbie Jean and Crystal have been sober for five years and have received therapy. Crystal is even going to school and Bloomfield is encouraging her to write her memoirs. Steven accepts responsibility for his actions and is also receiving psychotherapy in prison.

“He has a lot of remorse,” Bloomfield notes. “Increasingly so.”

But the film  ends by reminding viewers that Steven did, in fact, murder the priest in cold blood.

ends by reminding viewers that Steven did, in fact, murder the priest in cold blood.

At least some good came from his death, Bloomfield hastens to point out. “It served as the means by which Bobbie Jean and Crystal were finally able to break the cycle of abuse that traces back to their grandfather and perhaps beyond.”

According to a number of studies conducted in the U.S. and U.K.,  roughly one in ten male victims of childhood sexual abuse go on to physically or sexually abuse their own or other children as adults. But the risk is far greater – perhaps as high as one in three – for sexually-abused children who, like Steven, come from severely dysfunctional families. Although psychologically complex and subject to numerous qualifications, many psychologists theorize that by becoming an abuser,

roughly one in ten male victims of childhood sexual abuse go on to physically or sexually abuse their own or other children as adults. But the risk is far greater – perhaps as high as one in three – for sexually-abused children who, like Steven, come from severely dysfunctional families. Although psychologically complex and subject to numerous qualifications, many psychologists theorize that by becoming an abuser,  someone who has been abused can play the role of the more powerful person in the relationship in an attempt to overcome the powerlessness they felt when they were being abused. People who have been abused carry a lot of anger about what happened to them and abuse can be a way to express that anger. They may even try to kill before being killed themselves.

someone who has been abused can play the role of the more powerful person in the relationship in an attempt to overcome the powerlessness they felt when they were being abused. People who have been abused carry a lot of anger about what happened to them and abuse can be a way to express that anger. They may even try to kill before being killed themselves.

“I think that  Father Rene’ would have been willing to die to break this cycle,” Bloomfield speculates.

Father Rene’ would have been willing to die to break this cycle,” Bloomfield speculates.

He was that type of guy.

Of course there are other studies that dispute the cycle of abuse notion, and even those who subscribe to it readily note that not everyone who has experienced sexual abuse as a child goes on to become an abuser. Ironically, toward the end of the filming, Bloomfield and his team discovered that Father Rene had himself been sexually abused by a family member when he was a little boy. But even Steven Murray admits that he was a good and decent man who was just trying to help him and  as many others as he possibly could.

as many others as he possibly could.

Given the scope and complexity of the film’s storyline, its sophisticated structure and execution, and the depth of its themes (which also include guilt and forgiveness), it’s easy to see why Where There Is Darkness is the Fort Myers Film Festival’s Best Documentary 2019.

April 17, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.