Children of the Everglades

Children of the Everglades was part of the Alliance for the Arts’ Art in Flight program. It was taken down in February 2013. Information about the exhibit remains here through March 31, 2013. After that time, information about the exhibition will be archived. [Ed.]

Children of the Everglades was part of the Alliance for the Arts’ Art in Flight program. It was taken down in February 2013. Information about the exhibit remains here through March 31, 2013. After that time, information about the exhibition will be archived. [Ed.]

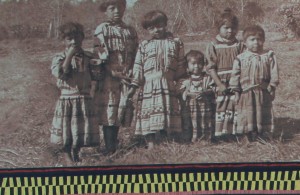

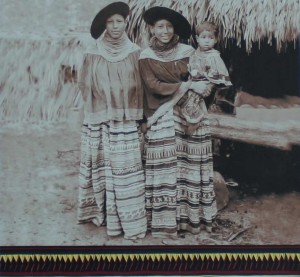

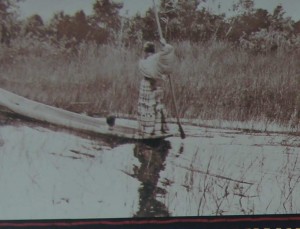

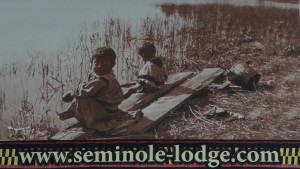

Children of the Everglades consists of large scale photographs from the W. Stanley Hanson and Robert D. Mitchell Collection of Seminole Indian Photographs, which is currently archived at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives. The exhibit provides both a glimpse into the lives of the Seminole-Miccosukee Indian children and authentic artifacts including patchwork dresses and jackets, sweet grass or pine needle baskets, palmetto dolls and historical documents.

Children of the Everglades consists of large scale photographs from the W. Stanley Hanson and Robert D. Mitchell Collection of Seminole Indian Photographs, which is currently archived at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives. The exhibit provides both a glimpse into the lives of the Seminole-Miccosukee Indian children and authentic artifacts including patchwork dresses and jackets, sweet grass or pine needle baskets, palmetto dolls and historical documents.

W. Stanley Hanson was the son of a turn-of-the-century Fort Myers doctor. Better known as the “White Medicine Man,” Hanson grew up among the Seminole-Miccosukee Indians and became a trusted friend and advocate. Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly to defend the tribe’s land and traditional way of life, served as a translator, and provided food and medicine to the tribe. In 1937, Hanson became a Seminole guide and interpreter under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration. The photographs and documents in the Hanson Family Archives provide a unique insider view of Seminole-Miccosukee Indian life and the fascinating relationship between these American Indians and the “White Medicine Man.”

W. Stanley Hanson was the son of a turn-of-the-century Fort Myers doctor. Better known as the “White Medicine Man,” Hanson grew up among the Seminole-Miccosukee Indians and became a trusted friend and advocate. Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly to defend the tribe’s land and traditional way of life, served as a translator, and provided food and medicine to the tribe. In 1937, Hanson became a Seminole guide and interpreter under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration. The photographs and documents in the Hanson Family Archives provide a unique insider view of Seminole-Miccosukee Indian life and the fascinating relationship between these American Indians and the “White Medicine Man.”

Additional sponsors for the Children of the Everglades exhibit include the Smithsonian Institution, Family Thrift Center, Carter-Pritchett Advertising, Scott Carter Signs, Owen Studio and MMT Printers.

More About the Hanson Family Archives

Passed down through five generations of one of Fort Myers’ first families, the Hanson Family Archives is a collection of more than 1,000 historic documents and images from 1884 to the mid-20th century. The collection is a treasure trove of information about the historic places, people and institutions of Southwest Florida, providing unrivalled insight into the community’s relationship with the neighboring Seminole-Miccosukee Indians.

Passed down through five generations of one of Fort Myers’ first families, the Hanson Family Archives is a collection of more than 1,000 historic documents and images from 1884 to the mid-20th century. The collection is a treasure trove of information about the historic places, people and institutions of Southwest Florida, providing unrivalled insight into the community’s relationship with the neighboring Seminole-Miccosukee Indians.

The Hanson family first planted its roots in Southwest Florida in 1884 when London-born Dr. Wm. Hanson and his wife, Julia Allen Hanson, opted to settle in Fort Myers rather than continue on to Cuba as they’d originally planned. Dr. Hanson became Thomas Edison’s physician and the Seminole-Miccosukee Indians’ doctor as well, and was also one of Fort Myers’ first real estate developers. Active in almost every movement or institution in Southwest Florida and beyond, Julia was called “the most beloved woman in Florida” upon her death in 1934.

The Hanson family first planted its roots in Southwest Florida in 1884 when London-born Dr. Wm. Hanson and his wife, Julia Allen Hanson, opted to settle in Fort Myers rather than continue on to Cuba as they’d originally planned. Dr. Hanson became Thomas Edison’s physician and the Seminole-Miccosukee Indians’ doctor as well, and was also one of Fort Myers’ first real estate developers. Active in almost every movement or institution in Southwest Florida and beyond, Julia was called “the most beloved woman in Florida” upon her death in 1934.

W. Stanley Hanson was born the year before his parents settled in Fort Myers. Growing up, he observed Seminole Indians at the general store. Most settlers knew only that the Seminoles traded venison and pelts and wore colorful costumes. But thanks to his parents, Stanley knew more. After the United States purchased Florida from Spain in 1821, the new government agreed to protect Seminole lands. But as settlement increased, the same government encroached upon their territory, resulting in the Seminole Wars. In 1855, it was the soldiers garrisoned at Fort Myers that provoked the Third Seminole War, a campaign that ended when Chief Billy Bowlegs agreed for a price to be resettled on land in Oklahoma. But not all the Seminoles boarded the steamer Grey Cloud with Billy Bowlegs. The few who remained went deeper into the Everglades and it was nearly two decades before they’d emerge to trade with the cattle ranchers and others who settled Fort Myers after the breastworks were abandoned following the end of the Civil War.

W. Stanley Hanson was born the year before his parents settled in Fort Myers. Growing up, he observed Seminole Indians at the general store. Most settlers knew only that the Seminoles traded venison and pelts and wore colorful costumes. But thanks to his parents, Stanley knew more. After the United States purchased Florida from Spain in 1821, the new government agreed to protect Seminole lands. But as settlement increased, the same government encroached upon their territory, resulting in the Seminole Wars. In 1855, it was the soldiers garrisoned at Fort Myers that provoked the Third Seminole War, a campaign that ended when Chief Billy Bowlegs agreed for a price to be resettled on land in Oklahoma. But not all the Seminoles boarded the steamer Grey Cloud with Billy Bowlegs. The few who remained went deeper into the Everglades and it was nearly two decades before they’d emerge to trade with the cattle ranchers and others who settled Fort Myers after the breastworks were abandoned following the end of the Civil War.

Hanson’s father and mother admired and respected the Seminoles. Dr. Hanson opened his practice to them. Julia mobilized local church groups and community clubs to help in hard times. When he came home from school, Stanley often found young Seminole boys waiting outside his father’s office. While his father treated the boys’ parents, the children played together. Stanley probably learned his first words of the Seminole language then.

From the time he was a teen, Hanson worked to help the Seminoles, first through a church-sponsored program and then as head of the Seminole Agency. But in 1926, the Seminole Agency office was transferred from Fort Myers to a 360-acre reservation in Dania in a thinly-veiled ploy designed to separate the Seminole nation from the wetlands they’d occupied since the 1850s. Once considered uninhabitable, the land occupied by the Seminoles became attractive to developers during the land boom of the mid-1920s for irrigation projects and subdivisions. “If a majority of the approximately 500 remaining Seminoles relocated to the reservation,” noted writer Michele Wehrwein Albion for Gulfshore Life Magazine in 2002, “it would be easier to justify moving out a few stragglers.”

But with Hanson’s intervention, the Seminoles retained their land. The respect he gained among the Seminoles led them to ask him to decide on the punishment to be meted out to a man who had killed a fellow tribesman in a drunken rage. Michele Wehrwein Albion recounts what happened next: “One of the elders, old Billy Fewell, he took off his turban and he put it on my father’s head. ‘Now you me, and me you.’ So my father sat in his place. They talked together about the man and what to do. My father was thinking about Solomon and he said, ‘If you kill this man, then you will have two families without a head.’ He told them that as punishment, he should support the other man’s wife and family. And that’s what they did. The decision was reported in newspapers throughout the state …. The white press called Hanson a ‘white medicine man’ because he had been asked to join the council of elders in making the decision. This title stuck with Hanson for the rest of his life.”

While his intervention had won him the respect and gratitude of the Indian nation, it made him powerful enemies both in Tallahassee and Washington, where a barrage of initiatives were launched to “rehabilitate” the tribe and force the Seminoles and Miccosukee to embrace white culture in derogation of their own traditions and heritage. Hanson fought against such programs, and to dispel myths about the tribe prevailing among politicians and the general public alike, Hanson launched his own campaign to offer a true portrait of his friends’ lives. With their permission, he recorded their lives in hundreds of photographs, writings and drawings, illuminating a world that had previously been invisible to outsiders.

During the Great Depression, Hanson helped the Seminoles trademark their goods and find places to sell their traditional crafts in order to raise money for food they could not grow or hunt. And after a lifetime of volunteering with the Seminoles, Hanson finally obtained a paid position in 1937 when he was hired as a guide and interpreter under the auspices of the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s recovery programs. It was a position Hanson held until his death from a cerebral aneurysm on April 4, 1945.

The letters and writings collected by Hanson, including correspondence from Presidents and legendary industrialists, were passed to the late W. Stanley Hanson, Jr., founder of Hanson Real Estate Advisors (HREA), and his wife, Mary Ellen Hanson, the great grand daughter of Manuel A. Gonzalez, Fort Myers’ first settler. The Hanson Family Archives and HREA are led by the couple’s son, fifth-generation Fort Myers resident Woody Hanson.

Fast Facts.

For more information on the exhibit, the Hanson Family Archives and the “White Medicine Man”, visit www.Seminole-Lodge.com.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.