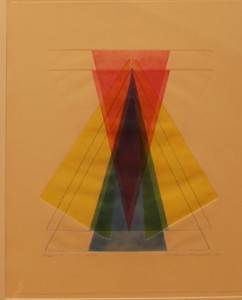

Littleton Studios Vitreography Prints

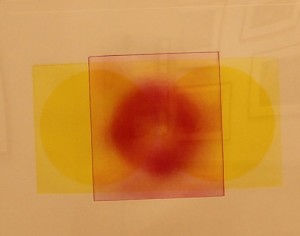

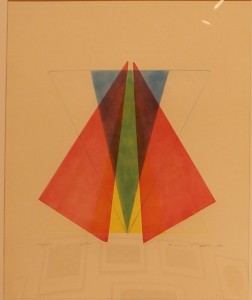

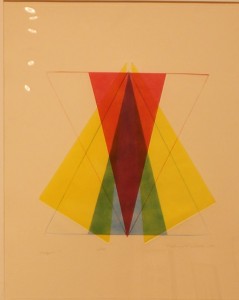

Included in the permanent collection of Florida Gulf Coast University are 70 prints created by Harvey Littleton and other artists using vitreography, a technique he developed at his studio in Spruce Pine, North Carolina. Donated by the printmaker’s daughter, Carol Littleton Shay, the gift to FGCU’s permanent collection was highlighted by an exhibition in the main gallery during the Fall of 2014 titled Harvey Littleton: No Secrets.

Included in the permanent collection of Florida Gulf Coast University are 70 prints created by Harvey Littleton and other artists using vitreography, a technique he developed at his studio in Spruce Pine, North Carolina. Donated by the printmaker’s daughter, Carol Littleton Shay, the gift to FGCU’s permanent collection was highlighted by an exhibition in the main gallery during the Fall of 2014 titled Harvey Littleton: No Secrets.

While Littleton’s name is more commonly associated with the studio glass movement in the United States, which he founded and pioneered, he also developed later in his career a process for making prints from glass plates. Artists from all over the world came to Littleton Studios to learn his process, and with Littleton’s tutelage, Dale Chihuly, Warrington Colescott, Hollis Sigler and a host of other glass artists, painters, potters and printmakers created diverse abstract, figurative and political works of art that explored the expressive power of the medium.

While Littleton’s name is more commonly associated with the studio glass movement in the United States, which he founded and pioneered, he also developed later in his career a process for making prints from glass plates. Artists from all over the world came to Littleton Studios to learn his process, and with Littleton’s tutelage, Dale Chihuly, Warrington Colescott, Hollis Sigler and a host of other glass artists, painters, potters and printmakers created diverse abstract, figurative and political works of art that explored the expressive power of the medium.

Significance of Littleton Studio Prints to FGCU Collection

The Littleton Studio prints provide the FGCU collection with an identity and academic significance. “A collection has to have a main focus,” explains FGCU Art Gallery Director John Loscuito. “The faculty here mainly teaches contemporary art practices, so the gallery needs to collect contemporary art. This is a significant gift and establishes the FGCU Art Galleries as collecting artworks by world-renowned artists.”

The Littleton Studio prints provide the FGCU collection with an identity and academic significance. “A collection has to have a main focus,” explains FGCU Art Gallery Director John Loscuito. “The faculty here mainly teaches contemporary art practices, so the gallery needs to collect contemporary art. This is a significant gift and establishes the FGCU Art Galleries as collecting artworks by world-renowned artists.”

Teaching Resource

The Littleton Studio prints will also serve as an important teaching tool. While vitreography is not currently part of the FGCU art curriculum, Associate Professor Andy Owen hopes to have the resources someday to add vitreography to the other printmaking techniques he teaches at FGCU. Until that happens, students will benefit in other ways from being able to study the Littleton Studios print collection.

The Littleton Studio prints will also serve as an important teaching tool. While vitreography is not currently part of the FGCU art curriculum, Associate Professor Andy Owen hopes to have the resources someday to add vitreography to the other printmaking techniques he teaches at FGCU. Until that happens, students will benefit in other ways from being able to study the Littleton Studios print collection.

“It’s a really, really valuable teaching tool to have  access to the works on a regular basis,” says Owen, who joined Littleton as a master printmaker right out of graduate school and remained friends with the artist until Littleton’s death in December of 2013. “These artists deal with a broad range of content. It’s a rich resource for students.”

access to the works on a regular basis,” says Owen, who joined Littleton as a master printmaker right out of graduate school and remained friends with the artist until Littleton’s death in December of 2013. “These artists deal with a broad range of content. It’s a rich resource for students.”

What is Vitreography?

Vitreography is a method of creating fine art prints from glass plates. Images are sandblasted into the glass, and the texturized surface holds ink effectively until it is transferred to paper.

Vitreography is a method of creating fine art prints from glass plates. Images are sandblasted into the glass, and the texturized surface holds ink effectively until it is transferred to paper.

Glass plates offer a number of advantages over traditional copper and metal plates. Because the roughly 3/8ths of an inch thick glass plates hold up well under printing compression, they last longer, enabling artists to produce a greater quantity of high-quality prints.

“For the viewer, there’s a purity of color that comes off glass,” Owen says. “The ink doesn’t oxidize like with metal plates.” This is particularly important with colors like yellows and whites, which can turn green or gray when they come into contact with metal plates. And intaglio vitreographs have the added advantage over metal in that the glass plate wipes cleanly in non-image areas, allowing bright white to coincide with black “that is velvety as a mezzotint” in the finished print, according to Janus Press’ Claire Van Vliet.

“For the viewer, there’s a purity of color that comes off glass,” Owen says. “The ink doesn’t oxidize like with metal plates.” This is particularly important with colors like yellows and whites, which can turn green or gray when they come into contact with metal plates. And intaglio vitreographs have the added advantage over metal in that the glass plate wipes cleanly in non-image areas, allowing bright white to coincide with black “that is velvety as a mezzotint” in the finished print, according to Janus Press’ Claire Van Vliet.

Glass plates can also facilitate the drawing process as the artist can place his or her drawing face down on a light table (to allow for reversal of the image when printed) and place the vitreograph plate on top of it.

How Littleton Developed the Technique

While still a tenured professor of art at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Harvey Littleton taught a workshop in cold-working techniques for glass artists. As the term implies, cold-working involves carving, grinding or engraving cold (as opposed to hot or molten) glass or sandblasting it with abrasives in order to mold or shape the glass or texture its surface. During the course of experimenting with various resists for

While still a tenured professor of art at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Harvey Littleton taught a workshop in cold-working techniques for glass artists. As the term implies, cold-working involves carving, grinding or engraving cold (as opposed to hot or molten) glass or sandblasting it with abrasives in order to mold or shape the glass or texture its surface. During the course of experimenting with various resists for  sandblasting, Littleton became intrigued by the possibility of making prints from glass. After Littleton had Warrington Colescott ink five of the sandblasted plates from the workshop and successfully print them onto paper, Littleton procured a research grant from the University and refined the development process.

sandblasting, Littleton became intrigued by the possibility of making prints from glass. After Littleton had Warrington Colescott ink five of the sandblasted plates from the workshop and successfully print them onto paper, Littleton procured a research grant from the University and refined the development process.

At the end of the grant period in 1976, Littleton retired and moved to Spruce Pine, North Carolina, where he promptly set up a glass studio that contained space for an etching press for vitreograph prints. But it was not until he hired Sandy Willcox as a part-time printer in 1981 that he began to widely share his glass plate printing technique with other artists.

At the end of the grant period in 1976, Littleton retired and moved to Spruce Pine, North Carolina, where he promptly set up a glass studio that contained space for an etching press for vitreograph prints. But it was not until he hired Sandy Willcox as a part-time printer in 1981 that he began to widely share his glass plate printing technique with other artists.

He encouraged Willcox, followed by Ken Carter, Billy Bernstein, Erwin Eisch and Ann Wolff to experiment with the technique. At Littleton’s invitation, Jane Kessler of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina looked at the resulting prints in 1982 and she recommended that he bring

He encouraged Willcox, followed by Ken Carter, Billy Bernstein, Erwin Eisch and Ann Wolff to experiment with the technique. At Littleton’s invitation, Jane Kessler of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina looked at the resulting prints in 1982 and she recommended that he bring  in other printmakers and artists to explore the medium even further. Littleton secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for this purpose, and painters Walter Darby Bannard, Ed Blackburn and Hollis Sigler came to Spruce Pine to team up with master printers Paul Maguire of Flatrock Press and June Lambla, who had apprenticed at Crown Point Press. Between 1985 and 1987, Bannard, Blackburn and Siger each produced a handful of prints which formed the nuclei of an exhibition at the Mint Museum in 1987 which included a catalog detailing these and other artists’ research in glass plate printmaking.

in other printmakers and artists to explore the medium even further. Littleton secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for this purpose, and painters Walter Darby Bannard, Ed Blackburn and Hollis Sigler came to Spruce Pine to team up with master printers Paul Maguire of Flatrock Press and June Lambla, who had apprenticed at Crown Point Press. Between 1985 and 1987, Bannard, Blackburn and Siger each produced a handful of prints which formed the nuclei of an exhibition at the Mint Museum in 1987 which included a catalog detailing these and other artists’ research in glass plate printmaking.

In 1998, Littleton asked artists Bonnie Pierce Lhotka, Karin Schminke and Dorothy Simpson Krause to try their hand at combining digital images with vitreographic processes. This “Digital Atelier” printed digital images onto clear transfer film using a large format inkjet printer, transferring them to paper in the course of the etching process along with glass plate imagery processed in the intaglio and siligraph techniques.

In 1998, Littleton asked artists Bonnie Pierce Lhotka, Karin Schminke and Dorothy Simpson Krause to try their hand at combining digital images with vitreographic processes. This “Digital Atelier” printed digital images onto clear transfer film using a large format inkjet printer, transferring them to paper in the course of the etching process along with glass plate imagery processed in the intaglio and siligraph techniques.

The Littlteon Studio Vitreography Artists

Between 1981 and Harvey Littleton’s death in December of 2013, over 110 artists worked in collaboration with Littleton Studios to publish vitreograph prints, including Dale Chihuly, Erwin Eisch, Shane Fero, Stanislav Libensky, Paul

Between 1981 and Harvey Littleton’s death in December of 2013, over 110 artists worked in collaboration with Littleton Studios to publish vitreograph prints, including Dale Chihuly, Erwin Eisch, Shane Fero, Stanislav Libensky, Paul  Stankard, Therman Statom, Sybren Valkema, Ann Wolff, Walter Darby Bannard, Louisa Chase, Herb Jackson, Mildred Thompson, Emilio Vedova, John Wilde, Cynthia Bringle, John Glick, Sergei Isupov, Italo Scanga, Glen Alps, Ken Kerslake, Karen Kunc, Judith O’Rourke and Dan Welden.

Stankard, Therman Statom, Sybren Valkema, Ann Wolff, Walter Darby Bannard, Louisa Chase, Herb Jackson, Mildred Thompson, Emilio Vedova, John Wilde, Cynthia Bringle, John Glick, Sergei Isupov, Italo Scanga, Glen Alps, Ken Kerslake, Karen Kunc, Judith O’Rourke and Dan Welden.

Major Littleton Studio Vitreograph Exhibitions

FGCU commemorated the gift of the Littleton Studios prints with an exhibition titled Harvey Littleton: No Secrets. The show was just the latest in a long line of vitreograph exhibitions dating back to 1975, when a medley of Littleton’s intaglio prints were displayed at the Brooks Memorial Art Museum in Memphis, Tennessee.

FGCU commemorated the gift of the Littleton Studios prints with an exhibition titled Harvey Littleton: No Secrets. The show was just the latest in a long line of vitreograph exhibitions dating back to 1975, when a medley of Littleton’s intaglio prints were displayed at the Brooks Memorial Art Museum in Memphis, Tennessee.

More than a decade passed before the next exhibition, a group show by 17 Littleton Studio printmakers, painters and glass artists in 1986 at Western Carolina University. The following year, the Mint Museum mounted a group exhibition titled Luminous Impressions: Prints from Glass Plates featuring  vitreographs by 19 artists including Dale Chihuly and Connor Everts. After another early group show in Coburg, Germany, the University of Florida partnered with the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1993 to host Vitreographs: Collaborative Works from the Littleton Studios and the Center for the Arts in Vero Beach, Florida put on Vitreographs: Collaborative Works from Littleton Studio in 1997.

vitreographs by 19 artists including Dale Chihuly and Connor Everts. After another early group show in Coburg, Germany, the University of Florida partnered with the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1993 to host Vitreographs: Collaborative Works from the Littleton Studios and the Center for the Arts in Vero Beach, Florida put on Vitreographs: Collaborative Works from Littleton Studio in 1997.

Recent group exhibitions include Reflections on a Legacy: Vitreographs from Littleton Studios at Appalachian State University in North Carolina in 2006 and Harvey K. Littleton  & Friends: A Legacy of Transforming Object, Image & Idea at Western Carolina University in 2006-2007. Curator Martin DeWitt said in the catalog that accompanied 75 artworks by 17 artists including vitreographs alongside works in glass, clay, ceramics, painting and art book, “Not only is Littleton credited to be the father of the contemporary studio glass movement in the United States …. he is also inventor and progenitor of the versatile and unique vitreographic printmaking process.”

& Friends: A Legacy of Transforming Object, Image & Idea at Western Carolina University in 2006-2007. Curator Martin DeWitt said in the catalog that accompanied 75 artworks by 17 artists including vitreographs alongside works in glass, clay, ceramics, painting and art book, “Not only is Littleton credited to be the father of the contemporary studio glass movement in the United States …. he is also inventor and progenitor of the versatile and unique vitreographic printmaking process.”

Public Collections

Besides Florida Gulf Coast University, vitreograph prints can be found today in museum and corporate collections across the United States, including the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Art in San Francisco, Burroughs Chapin Art Museum in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the Cincinnati Museum of Art, the Corning Museum of Glass, Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida in Gainesville, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut (which maintains an archive of more than 500 vitreographs), the Portland Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, and the Vero Beach Museum of Art. The Fine Art Museum of Western Carolina University holds an archive of 723 vitreographic editions published at Littleton Studios. Thus, the 70 prints gifted to FGCU by Carol Littleton Shay is significant in the context of the history of vitreography in the United States.

Besides Florida Gulf Coast University, vitreograph prints can be found today in museum and corporate collections across the United States, including the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Art in San Francisco, Burroughs Chapin Art Museum in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the Cincinnati Museum of Art, the Corning Museum of Glass, Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida in Gainesville, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut (which maintains an archive of more than 500 vitreographs), the Portland Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, and the Vero Beach Museum of Art. The Fine Art Museum of Western Carolina University holds an archive of 723 vitreographic editions published at Littleton Studios. Thus, the 70 prints gifted to FGCU by Carol Littleton Shay is significant in the context of the history of vitreography in the United States.

Father of the Glass Art Movement

Although Harvey Littleton developed vitreography, he is better known as the founder of the art glass movement.

Although Harvey Littleton developed vitreography, he is better known as the founder of the art glass movement.

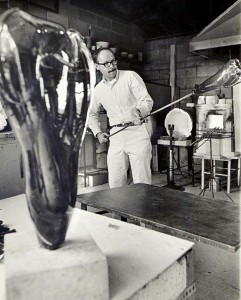

Trained as a ceramicist, Littleton began experimenting with hot glass in his studio in the 1950s. During this time, he began scouring the world to assemble the knowledge and hardware he would need in order to melt glass beads in a backyard furnace to make art by himself, thereby  breaking with the glassblowing tradition in which three or four apprentices assisted a craftsman.

breaking with the glassblowing tradition in which three or four apprentices assisted a craftsman.

At the time, fine glassmaking was the exclusive domain of large factories like Steuben Glass Works in upstate New York and the renowned glass factories in Murano, Italy. In these factories, fine glassmaking was a collaborative process. An artist created a design which he then provided to the factory’s glassmakers, who produced it. But with grants, fellowships and financing from the Toledo Museum of Art, Littleton developed a one-person glass production line with the help of friend, aspiring artist and Johnson Manville Corporation research scientist Dominick Labino.

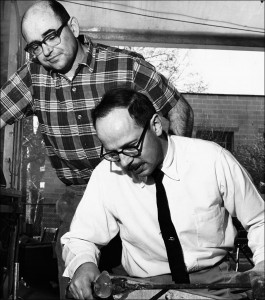

Littleton first attracted attention to what he was doing when he demonstrated the process on the grounds of the Toledo Museum in 1962.Through the fall of 1962 and spring of 1963, he taught glass in a garage at his farm to six students under an independent study program. But the following year, he secured University of Wisconsin funding that enabled him to rent and equip an off-campus glass department in Madison. Through the University’s glass program, Littleton went on to train many prominent glass artists, including Dale Chihuly, Marvin Lipofsky, Christopher Ries, Bill Boysen, Fritz Dreisbach, Sam Herman, Tom McGlauchlin and Michael Taylor.

Littleton first attracted attention to what he was doing when he demonstrated the process on the grounds of the Toledo Museum in 1962.Through the fall of 1962 and spring of 1963, he taught glass in a garage at his farm to six students under an independent study program. But the following year, he secured University of Wisconsin funding that enabled him to rent and equip an off-campus glass department in Madison. Through the University’s glass program, Littleton went on to train many prominent glass artists, including Dale Chihuly, Marvin Lipofsky, Christopher Ries, Bill Boysen, Fritz Dreisbach, Sam Herman, Tom McGlauchlin and Michael Taylor.

With the launching of the glass department, Littleton also became a self-described evangelist for the medium, giving lectures at university art departments and other forums throughout the midwest and northeastern United States about the potential of glass as a medium for the studio artist. He realized that making his own glasswork was not enough to kindle the level of interest the medium

With the launching of the glass department, Littleton also became a self-described evangelist for the medium, giving lectures at university art departments and other forums throughout the midwest and northeastern United States about the potential of glass as a medium for the studio artist. He realized that making his own glasswork was not enough to kindle the level of interest the medium  deserved. “He knew there had to be many more artists, many galleries, college courses – a whole infrastructure – for studio glass to become a movement,” says his biographer, Joan Ealconer Byrd.

deserved. “He knew there had to be many more artists, many galleries, college courses – a whole infrastructure – for studio glass to become a movement,” says his biographer, Joan Ealconer Byrd.

Since then, dozens more college-based glass programs have been founded throughout the country, most by Littleton’s former students, including Marvin Lipofsky, who started a glass program at the University of California at Berkeley, and Dale Chihuly, who developed the glass program at the Rhode Island School of Design and later was a founder of Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington.

In a 1999 oral history interview for Archives of American Art, Littleton compared the centuries-old glassblowing technique craftsmen used in factories like those in Murano with the method he used and taught others. “In the old system,” he said, “they were taught to make each piece exactly like the previous one. Our training teaches someone to make each piece different.”

In a 1999 oral history interview for Archives of American Art, Littleton compared the centuries-old glassblowing technique craftsmen used in factories like those in Murano with the method he used and taught others. “In the old system,” he said, “they were taught to make each piece exactly like the previous one. Our training teaches someone to make each piece different.”

Littleton’s Glass Art

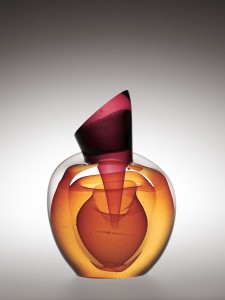

Littleton’s glass art dates back to the early days of his development of the technology for single-artist fine glassblowing in 1962. Exploring the inherent qualities of the medium, Littleton worked in series with simple forms to draw attention to the complex interplay of transparent glass with multiple overlays of thin color. But perhaps his best known body of work was his Topographical Geometry series, made between 1983 and 1989. Included under this heading are his signature Arc forms and Crowns, as well as his late Lyrical Movement and Implied Movement sculptural groups. In 1989 chronic back problems forced Littleton to retire from working in the hot glass medium.

Littleton’s glass art dates back to the early days of his development of the technology for single-artist fine glassblowing in 1962. Exploring the inherent qualities of the medium, Littleton worked in series with simple forms to draw attention to the complex interplay of transparent glass with multiple overlays of thin color. But perhaps his best known body of work was his Topographical Geometry series, made between 1983 and 1989. Included under this heading are his signature Arc forms and Crowns, as well as his late Lyrical Movement and Implied Movement sculptural groups. In 1989 chronic back problems forced Littleton to retire from working in the hot glass medium.

Littleton’s glass art can be found today in the permanent collections of museums around the globe, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corning Museum of Glass, Detroit Institute of Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Arts & Design, Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Smithsonian Institution and the Toledo Museum of Art. Overseas, his work is in Glasmuseet

Littleton’s glass art can be found today in the permanent collections of museums around the globe, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corning Museum of Glass, Detroit Institute of Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Arts & Design, Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Smithsonian Institution and the Toledo Museum of Art. Overseas, his work is in Glasmuseet  Ebeltoft in Denmark, Museum Bellrive in Zurich, Switzerland, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Holland, National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, Japan, Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art in Sapporo in Japan, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Glasmuseum Frauenau and the Decorative Museums in Frankfurt, Hamburg, Prague and Vienna

Ebeltoft in Denmark, Museum Bellrive in Zurich, Switzerland, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Holland, National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, Japan, Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art in Sapporo in Japan, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Glasmuseum Frauenau and the Decorative Museums in Frankfurt, Hamburg, Prague and Vienna

A Word about Carol Littleton Shay

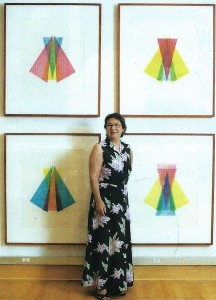

Carol Littleton Shay serves as director of Littleton Studios. In that capacity, she donated more than 70 prints by her father and other Littleton Studios artists to Florida Gulf Coast University. “I wanted to help promote the process and possibilities of this medium for the next generation,” she explained during the opening of Harvey Littleton: No Secrets, the exhibition that marked the occasion of the gift’s announcement. “It’s his legacy. These works need to be seen in order to be known and remembered.”

Carol Littleton Shay serves as director of Littleton Studios. In that capacity, she donated more than 70 prints by her father and other Littleton Studios artists to Florida Gulf Coast University. “I wanted to help promote the process and possibilities of this medium for the next generation,” she explained during the opening of Harvey Littleton: No Secrets, the exhibition that marked the occasion of the gift’s announcement. “It’s his legacy. These works need to be seen in order to be known and remembered.”

Shay is one of four children born to Harvey and Bess Tamura Littleton. All work in the field of glass art. Tom Littleton owns and manages Spruce Pine Batch Company, which supplies batch (the dry ingredients used for purposes of making glass) to artists and art departments across the U.S. Maurine Littleton is the owner and director of Maurice Littleton Gallery in Washington, D.C., which specializes in glass art. John Littleton is a glass artist who lives and works in Bakersville, North Carolina with his wife and collaborative partner, Kate Vogel.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.