Marks & Brands

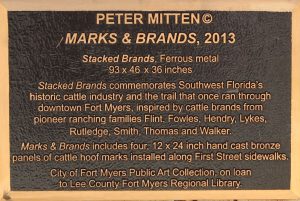

Marks & Brands is a site-specific sculptural installation that commemorates the rich traditions of the cattle industry that flourished in Southwest Florida during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was conceived, designed and fabricated by California sculptor and art instructor Peter Mitten, who was chosen from a field of three finalists and 112 applicants.

Marks & Brands is a site-specific sculptural installation that commemorates the rich traditions of the cattle industry that flourished in Southwest Florida during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was conceived, designed and fabricated by California sculptor and art instructor Peter Mitten, who was chosen from a field of three finalists and 112 applicants.

The installation consists of a large three-dimensional ferrous metal sculpture that is located in a water feature in the courtyard of the new Fort Myers Regional Library on First Street and Royal Palm Boulevard, and four bronze relief panels  containing the imprints of cattle hooves that have been inserted in the sidewalk running along First Street and McGregor Boulevard to identify the site of the historic cattle trail that once cut through the city.

containing the imprints of cattle hooves that have been inserted in the sidewalk running along First Street and McGregor Boulevard to identify the site of the historic cattle trail that once cut through the city.

It’s true. Between 1865 and roughly 1908, a crude dirt cattle trail sliced through Fort Myers. Connecting pasture lands in Fort Ogden and Fort Thompson to shipping pens and a deep water wharf built by Union soldiers in Punta Rassa in 1864, the road was dotted with scrub pens and stopovers like the cracker-style shack at the Edison & Ford Winter Estates that Jacob Summerlin put up for cattle drovers moving his herds down the old Wire Road  (now McGregor Boulevard). The weed-covered sand and dirt road was finally replaced with a paved thoroughfare in 1915 thanks to legendary civic leader Tootie McGregor Terry, who offered to cover the costs of paving the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa if the city and county would pick up the cost of paving Riverside Avenue from Whiskey Creek to the train station at Monroe and Main Street in downtown Fort Myers.

(now McGregor Boulevard). The weed-covered sand and dirt road was finally replaced with a paved thoroughfare in 1915 thanks to legendary civic leader Tootie McGregor Terry, who offered to cover the costs of paving the 20-mile stretch from Whiskey Creek to Punta Rassa if the city and county would pick up the cost of paving Riverside Avenue from Whiskey Creek to the train station at Monroe and Main Street in downtown Fort Myers.

For the 3D totemic piece, Mitten has stacked various cattle brand shapes in a calligraphic linear configuration that pays tribute to the “historic branding irons utilized by Lee County’s cattle ranchers to mark their cattle.” Known as Stacked Brands, the 400-500 pound rust-colored sculpture  stands eight feet in height, although it appears taller because it has been mounted on a 2 x 4 x 4 foot travertine clad pedestal which resides in the center of a shallow 12 foot wide by 77 foot long water feature that runs along the west side of the plaza opposite the library’s entrance. The sculpture is on loan to Lee County from the City of Fort Myers under a long-term lease in exchange for which Lee County agreed to install, light and maintain the piece, which has been sealed with three coats of clear Smart Coat sealer to protect it from corrosion and the sun’s UV rays.

stands eight feet in height, although it appears taller because it has been mounted on a 2 x 4 x 4 foot travertine clad pedestal which resides in the center of a shallow 12 foot wide by 77 foot long water feature that runs along the west side of the plaza opposite the library’s entrance. The sculpture is on loan to Lee County from the City of Fort Myers under a long-term lease in exchange for which Lee County agreed to install, light and maintain the piece, which has been sealed with three coats of clear Smart Coat sealer to protect it from corrosion and the sun’s UV rays.

The four 1 x 2 foot life-cast silicon bronze relief panels have been inserted in the sidewalk along First Street and McGregor Boulevard following an intensive  ADA and historic preservation review. Mitten fabricated each half-inch thick panel with rounded, ADA-compliant edges so that they could simply be bolted into the sidewalk with 3″ threaded rods and secured with epoxy.

ADA and historic preservation review. Mitten fabricated each half-inch thick panel with rounded, ADA-compliant edges so that they could simply be bolted into the sidewalk with 3″ threaded rods and secured with epoxy.

“It was important for me to visually mark the historic cattle trail as it  made its way from the ranches in eastern Lee County through downtown Fort Myers west toward Punta Rassa where cattle were loaded onto ships destined for Cuba and other ports,” notes Mitten. “Marking this trail became, for me, a powerful metaphor for passages that mark time, a recurrent theme in my public artworks for more than twenty years.”

made its way from the ranches in eastern Lee County through downtown Fort Myers west toward Punta Rassa where cattle were loaded onto ships destined for Cuba and other ports,” notes Mitten. “Marking this trail became, for me, a powerful metaphor for passages that mark time, a recurrent theme in my public artworks for more than twenty years.”

Marks & Brands is the 25th sculpture in the City of Fort Myers’ public art collection, which also maintains more than two dozen paintings, prints and photographs in its Portable Works Collection. When combined with works commissioned by the federal government, Lee County and other sources, there are more than 70 public artworks within the city limits, with most being concentrated in a four-square-block area in the downtown Fort Myers River District.

Marks & Brands is the 25th sculpture in the City of Fort Myers’ public art collection, which also maintains more than two dozen paintings, prints and photographs in its Portable Works Collection. When combined with works commissioned by the federal government, Lee County and other sources, there are more than 70 public artworks within the city limits, with most being concentrated in a four-square-block area in the downtown Fort Myers River District.

Fort Myers and the Cattle Industry

But for the cattle industry in Southwest Florida at the time of and in the years following the end of the Civil War, it is likely that there would be no Fort Myers today. Oh, there would probably be a town on the Caloosahatchee River, but it is doubtful it would be called Fort Myers and it would certainly not include the historic buildings that line First Street and dot the rest of the downtown Fort Myers River District. It is

But for the cattle industry in Southwest Florida at the time of and in the years following the end of the Civil War, it is likely that there would be no Fort Myers today. Oh, there would probably be a town on the Caloosahatchee River, but it is doubtful it would be called Fort Myers and it would certainly not include the historic buildings that line First Street and dot the rest of the downtown Fort Myers River District. It is  also highly improbable that Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, or the McGregors would have ever found their way to this part of Florida.

also highly improbable that Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, or the McGregors would have ever found their way to this part of Florida.

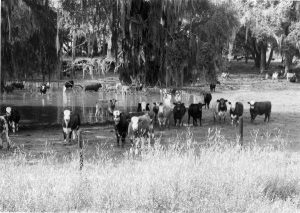

By the time forces under the command of General P.G.T. Beauregard opened fire on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Florida was one of the leading cattle-producing states in the South. And the Confederacy relied heavily on  Florida’s cattle ranchers for beef, hides and tallow. (Leather was vitally important not only for shoes, but cartridge boxes and harnesses for pulling artillery.) However, not all of Florida’s cattle went to feed and supply the Confederate Army. Because clothing, tobacco, salt and other provisions were in short supply due to the Union blockade, Florida ranchers diverted

Florida’s cattle ranchers for beef, hides and tallow. (Leather was vitally important not only for shoes, but cartridge boxes and harnesses for pulling artillery.) However, not all of Florida’s cattle went to feed and supply the Confederate Army. Because clothing, tobacco, salt and other provisions were in short supply due to the Union blockade, Florida ranchers diverted  thousands of head to blockade runners who sold their steers in Cuba, which was able and willing to pay more than three times what the Confederacy could pay – and in gold, clothing, home goods and food rather than Confederate dollars.

thousands of head to blockade runners who sold their steers in Cuba, which was able and willing to pay more than three times what the Confederacy could pay – and in gold, clothing, home goods and food rather than Confederate dollars.

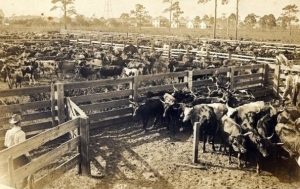

To interrupt the flow of cattle to both Confederate fighting forces  and the traders and fishermen who were thwarting the Union’s blockade, the Union re-garrisoned the abandoned redoubt on the Caloosahatchee known as Fort Myers with five companies from the 110th New York Infantry and the 2nd Florida Union Calvary. Between January 1, 1864 and the end of the Civil War, the soldiers

and the traders and fishermen who were thwarting the Union’s blockade, the Union re-garrisoned the abandoned redoubt on the Caloosahatchee known as Fort Myers with five companies from the 110th New York Infantry and the 2nd Florida Union Calvary. Between January 1, 1864 and the end of the Civil War, the soldiers  stationed there confiscated more than 4,500 head of cattle from ranches extending from Punta Gorda to as far north as Fort Meade. “Some of the cattle captured by raiders from the fort … were slaughtered at Fort Myers to supply meat for their garrison,” reports Karl H. Grismer in his book, The Story of Fort Myers. “Most of them, however, were driven overland to Punta Rassa, where they were loaded on transports and taken to Key West. The trail followed by these cattle

stationed there confiscated more than 4,500 head of cattle from ranches extending from Punta Gorda to as far north as Fort Meade. “Some of the cattle captured by raiders from the fort … were slaughtered at Fort Myers to supply meat for their garrison,” reports Karl H. Grismer in his book, The Story of Fort Myers. “Most of them, however, were driven overland to Punta Rassa, where they were loaded on transports and taken to Key West. The trail followed by these cattle  drives was the one which had been blazed in 1838 by Col. Persifer F. Smith during the war against the Indians …. [I]t became tramped down and so well defined that it was followed by cattlemen for many years after the Civil War ended.”

drives was the one which had been blazed in 1838 by Col. Persifer F. Smith during the war against the Indians …. [I]t became tramped down and so well defined that it was followed by cattlemen for many years after the Civil War ended.”

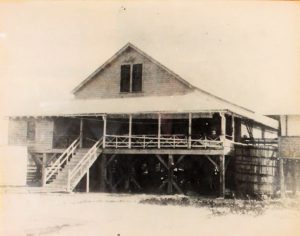

To facilitate the shipment of cattle from Punta Rassa, the Army built cow pens,  chutes, a long wharf into the deep waters not far from shore, and a 100 foot long by 50 foot wide barracks built atop 14 foot pilings. It was these facilities that lured Jacob Summerlin to the Fort Myers area in the months following Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox.

chutes, a long wharf into the deep waters not far from shore, and a 100 foot long by 50 foot wide barracks built atop 14 foot pilings. It was these facilities that lured Jacob Summerlin to the Fort Myers area in the months following Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox.

Jacob Summerlin got into the cattle business before the war when he traded 20 slaves he inherited for 6,000 head of cattle. Early on, he supplied the Confederacy with beef, but beginning in 1863, he teamed up with James McKay, Sr., a daring and highly successful blockade runner who operated from a base in Charlotte Harbor to the north. Whether he learned

got into the cattle business before the war when he traded 20 slaves he inherited for 6,000 head of cattle. Early on, he supplied the Confederacy with beef, but beginning in 1863, he teamed up with James McKay, Sr., a daring and highly successful blockade runner who operated from a base in Charlotte Harbor to the north. Whether he learned about Punta Rassa from McKay or by other means, Summerlin made the abandoned pens, chutes, wharf and barracks his base of operations for the continued export of cattle to Cuba and Key West within weeks following the end of the Civil War.

about Punta Rassa from McKay or by other means, Summerlin made the abandoned pens, chutes, wharf and barracks his base of operations for the continued export of cattle to Cuba and Key West within weeks following the end of the Civil War.

But Summerlin’s appropriation of these facilities was interrupted in 1867 when the Ocean Telegraph Company (which was later acquired by Western Union) took over the barracks and wharf under the provisions of a Congressional act that permitted a telegraph company “to take and use public land necessary for the stringing of line or the establishment of stations.”  The IOTC did not prohibit Summerlin from using the pens, chutes and wharf. But it did assess a port charge of 15 cents per head for his continued use of the shipping facilities.

The IOTC did not prohibit Summerlin from using the pens, chutes and wharf. But it did assess a port charge of 15 cents per head for his continued use of the shipping facilities.

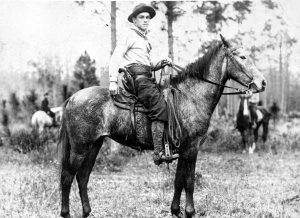

Summerlin’s export business accelerated in 1868 when Cuban insurrectionists began a ten-year war with their Spanish occupiers which increased their demand for beef. In no time at all, Summerlin’s agents began buying and driving ‘beeves” from ranches throughout central and northern Florida south toward Punta Rassa. Some herds crossed the Caloosahatchee at Fort Denaud; others at Fort Thompson. To facilitate these drives,  Summerlin constructed a crude road from Fort Ogden to Punta Rassa, building scrub pens and stopovers along the way including the cracker-style structure that Thomas Edison purchased in 1885 and converted into his Caretaker’s House. The town emerging from the remnants of the old fort was integrated into Summerlin’s cattle highway, which often saw herds exceeding a thousand head passing along present-day First Street.

Summerlin constructed a crude road from Fort Ogden to Punta Rassa, building scrub pens and stopovers along the way including the cracker-style structure that Thomas Edison purchased in 1885 and converted into his Caretaker’s House. The town emerging from the remnants of the old fort was integrated into Summerlin’s cattle highway, which often saw herds exceeding a thousand head passing along present-day First Street.

It  wasn’t long before other cattlemen began arriving in Punta Rassa intent on striking deals directly with buyers from Key West and Havana. F.A. Hendry and his brother Marion were among that group. Since Jacob and his son Samuel had the exclusive right to the IOTC facilities, the Hendrys and other cattlemen had to pay the Summerlins an augmented port fee for use of the pens, chutes and wharf.

wasn’t long before other cattlemen began arriving in Punta Rassa intent on striking deals directly with buyers from Key West and Havana. F.A. Hendry and his brother Marion were among that group. Since Jacob and his son Samuel had the exclusive right to the IOTC facilities, the Hendrys and other cattlemen had to pay the Summerlins an augmented port fee for use of the pens, chutes and wharf.

In October of 1873, the facilities were severely damaged by a hurricane. Ever the astute businessman, Jacob Summerlin decided he’d better construct his wharf and pens, and so he built a longer and even better pier farther up the point along with a hotel to compete with the hostel that the cable operator, George Shultz, was running out of

In October of 1873, the facilities were severely damaged by a hurricane. Ever the astute businessman, Jacob Summerlin decided he’d better construct his wharf and pens, and so he built a longer and even better pier farther up the point along with a hotel to compete with the hostel that the cable operator, George Shultz, was running out of  the old barracks that the Union soldiers had constructed in 1864. Jacob named his new hotel the Summerlin House. It not only provided room and board to drovers during their stays in Punta Rassa, but accommodations to cattle buyers visiting from Havana and Key West.

the old barracks that the Union soldiers had constructed in 1864. Jacob named his new hotel the Summerlin House. It not only provided room and board to drovers during their stays in Punta Rassa, but accommodations to cattle buyers visiting from Havana and Key West.

During the decade that followed the start of the Cuban insurrection, “165,669 head of cattle were shipped to Cuban ports and for them the cattlemen received $2,441,846 [which was] truly a princely sum during  those lean reconstruction years,” Grismer sums up. (Id. at 86.) But it wasn’t until the Hendrys moved into Fort Myers themselves that any of that money found its way to the small settlement on the banks of the Caloosahatchee.

those lean reconstruction years,” Grismer sums up. (Id. at 86.) But it wasn’t until the Hendrys moved into Fort Myers themselves that any of that money found its way to the small settlement on the banks of the Caloosahatchee.

The Hendrys decision to relocate to Fort Myers was actually prompted by the death of a six-year-old girl in May of 1873. Her name was Esther Ann Hendry, and she was the daughter of Charles and Jane Hendry. Charles and his family were living in an isolated two-room frontier shack in pasturelands near present-day Immokalee. In the aftermath of the girl’s death, Jane decided that she would no longer live far from civilization just to keep watch over the family’s cattle.  She and Charles arrived in Fort Myers four days later, and Captain Francis Asbury Hendry, Marion Hendry and three other closely-related families soon followed. All were familiar with the fort. F.A. Hendry had visited the fort twice during the Second Seminole War, once in 1853 and again a year later. He returned under less hospitable circumstances on February 20, 1865 when, as captain of a 131-man company that he raised and commanded himself, he joined with Major William Footman’s Cow Calvary or “Cattle Battalion” in an unsuccessful attack on the fort. Charles had also been to the fort during the Second Seminole War, when he brought Seminole prisoners there while a member of a Florida Volunteer boat company.

She and Charles arrived in Fort Myers four days later, and Captain Francis Asbury Hendry, Marion Hendry and three other closely-related families soon followed. All were familiar with the fort. F.A. Hendry had visited the fort twice during the Second Seminole War, once in 1853 and again a year later. He returned under less hospitable circumstances on February 20, 1865 when, as captain of a 131-man company that he raised and commanded himself, he joined with Major William Footman’s Cow Calvary or “Cattle Battalion” in an unsuccessful attack on the fort. Charles had also been to the fort during the Second Seminole War, when he brought Seminole prisoners there while a member of a Florida Volunteer boat company.  And all three had passed by the skeleton of the old fort numerous times as they led herds to the cow pens and wharves down river in Punta Rassa.

And all three had passed by the skeleton of the old fort numerous times as they led herds to the cow pens and wharves down river in Punta Rassa.

“All these newcomers were able, intelligent men, and all were destined to take prominent parts in the development of the Fort Myers area,” Karl Grismer writes. “Capt. F.A. Hendry became known as ‘The Father of Fort Myers,’ partly because of his many descendants but mainly because he fostered and took an active part in almost every worthy movement in the early days of the community.” (Id. at 91.) Capt. Hendry, in particular, quickly eclipsed the Summerlins as the principle cattle rancher in the area. With a herd in excess of 50,000 head,  he became known as the Cattle King of South Florida and one of the most influential leaders in both Fort Myers and Lee County as well. He served as a State Senator from 1875-1877, State Representative from 1893-1904, was on the first town council of Fort Myers in 1885 and also the first Lee County Commission in 1887. He was also one of the city’s ten founding fathers and

he became known as the Cattle King of South Florida and one of the most influential leaders in both Fort Myers and Lee County as well. He served as a State Senator from 1875-1877, State Representative from 1893-1904, was on the first town council of Fort Myers in 1885 and also the first Lee County Commission in 1887. He was also one of the city’s ten founding fathers and  chaired the meeting that resulted in the city’s incorporation on August 12, 1885.

chaired the meeting that resulted in the city’s incorporation on August 12, 1885.

Hendry and Summerlin were good for business. They brought with them a whole network of cattlemen, cow hunters, blacksmiths, cobblers and everyone else who attended to the cattlemen’s needs. Men in every line of endeavor began coming to Fort Myers.  “They could make a living here while at the same time get all the benefits of a fine climate, and fish and hunt to their heart’s content.” (Id. at 97.)

“They could make a living here while at the same time get all the benefits of a fine climate, and fish and hunt to their heart’s content.” (Id. at 97.)

While Fort Myers did have temperate weather and exceedingly fertile grounds, it could never have developed as a farming community because it lacked a way  to get its crops to market. The nearest railroad was an hour north of Tampa in Cedar Key. The nearest town of any consequence was Key West. And the river was filled with shoals and shallows that made shipping produce by boat impractical, if not impossible. “The infant village had one great asset – it was the one and only accessible trading center for a rapidly growing cattle region,” Grismer points out. “The importance

to get its crops to market. The nearest railroad was an hour north of Tampa in Cedar Key. The nearest town of any consequence was Key West. And the river was filled with shoals and shallows that made shipping produce by boat impractical, if not impossible. “The infant village had one great asset – it was the one and only accessible trading center for a rapidly growing cattle region,” Grismer points out. “The importance  of the cattle industry can best be shown by the fact that during one year in the 1870s, Captain Hendry shipped 12,896 head from Punta Rassa to Key West. The prices paid averaged $15. For all the cattle, he received approximately $200,000.”

of the cattle industry can best be shown by the fact that during one year in the 1870s, Captain Hendry shipped 12,896 head from Punta Rassa to Key West. The prices paid averaged $15. For all the cattle, he received approximately $200,000.”

The cattle industry drew people to the fledgling town not in one great migration, “but a few this year, and  a few next, the total always climbing.” Included in this influx were Dr. Thomas Langford and William H. Towles, who became prominent cattlemen in due course. And thus Fort Myers evolved into a rough-and-tumble cow town. Not fast, but slowly and deliberately until finally visionaries like Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Ambrose and Tootie McGregor came to lead Fort Myers into the age of invention, shifting the overall tenor and focus from cattle to citrus and tourism.

a few next, the total always climbing.” Included in this influx were Dr. Thomas Langford and William H. Towles, who became prominent cattlemen in due course. And thus Fort Myers evolved into a rough-and-tumble cow town. Not fast, but slowly and deliberately until finally visionaries like Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Ambrose and Tootie McGregor came to lead Fort Myers into the age of invention, shifting the overall tenor and focus from cattle to citrus and tourism.

About Peter Mitten

For 40 years Peter Mitten has been making and exhibiting sculptural ideas, drawings, and architectural design on a commissioned basis.

For 40 years Peter Mitten has been making and exhibiting sculptural ideas, drawings, and architectural design on a commissioned basis.

After receiving an MFA in sculpture in 1976 from Southern Illinois University School of Art and Design, Mitten moved to California for a college teaching position at Point Loma University. Launching his sculpting career at the same time, he quickly received favorable critical reviews and several awards, including “Best In Sculpture Division” at the 1982 Southern California Expo. In 1989, Peter moved to Boston, where he received a Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant to continue studio endeavors until his return to southern California in 1992. He now resides in Hemet, California.

Among  the public art pieces he has completed are installations at the San Diego County Library (Grove Canopy, fence and gate in cut and welded steel, 56′ x 10′ x 4″ – 2010), the Mt. San Jacinto College Library in Menifee, California (Polyhedron Stretch, right, painted wood – 2010), the UCSD Mathematics Department in La Jolla, California (Polyhedron Cloud, stainless steel – 2005), the Music Department at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego

the public art pieces he has completed are installations at the San Diego County Library (Grove Canopy, fence and gate in cut and welded steel, 56′ x 10′ x 4″ – 2010), the Mt. San Jacinto College Library in Menifee, California (Polyhedron Stretch, right, painted wood – 2010), the UCSD Mathematics Department in La Jolla, California (Polyhedron Cloud, stainless steel – 2005), the Music Department at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego  (Centenary Passage, cast bronze and granite, 120″ x 96″ x 96″ – 2002), the Escondido Transit Center (Hekkilk, cast, pigmented concrete, 96″ x 240″ x 168″ – 2000) and the Rapid Transit Center in Plano, Texas (Stele of Plano, right, cast bronze, twelve separate 48″ x 32″ sections 48″ x 32″ x 2″ – 1993), as well as in Belmont, Massachusetts and Prescott Valley, Arizona.

(Centenary Passage, cast bronze and granite, 120″ x 96″ x 96″ – 2002), the Escondido Transit Center (Hekkilk, cast, pigmented concrete, 96″ x 240″ x 168″ – 2000) and the Rapid Transit Center in Plano, Texas (Stele of Plano, right, cast bronze, twelve separate 48″ x 32″ sections 48″ x 32″ x 2″ – 1993), as well as in Belmont, Massachusetts and Prescott Valley, Arizona.

Mitten’s  work has been exhibited at the San Diego Botanical Gardens in Encinitas and by the Santa Ysabel Art Gallery in San Jacinto, California. His most recent one-person exhibition was in 2010 at Yuma Art Center in Yuma, Arizona.

work has been exhibited at the San Diego Botanical Gardens in Encinitas and by the Santa Ysabel Art Gallery in San Jacinto, California. His most recent one-person exhibition was in 2010 at Yuma Art Center in Yuma, Arizona.

“My work has been inspired by the hard surfaces, landscape and water drainage patterns in the southwest United States,” states Mitten. With a background in cast metals, he has interpreted canyons, valleys, rock outcroppings and distinctive areas along wilderness trails through small, medium and large-scale cast and fabricated metal, bronze, aluminum and iron, as well as granite and painted steel and wood in sizes ranging from desktop to 20 feet in  height.

height.

Peter’s recent work explores modular sculptural interpretations of micro and macroscopic systems.

Peter teaches life sculpture and three dimensional design at Mt. San Jacinto College in Menifee, and he remains involved in curriculum and teaching for the Oak Lake Art Center in Julian, California.

Fast Facts.

The Fort Myers Regional Library opened on Tuesday, December 10, 2013.

The Fort Myers Regional Library opened on Tuesday, December 10, 2013.- It was designed by Kevin Williams of BSSW Architects.

- Containing 40,000 square feet of space, the library is located on the corner of First Street and Royal Palm Avenue, roughly one block east of the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center.

The Fort Myers Regional Library replaces the Fort Myers-Lee County Public Library located at 2050 Central Avenue, Fort Myers, FL 33901, which was once home to Lorelei, a white marble sculpture that dates back to circa 1880 which the library chose to leave behind when it moved to its new quarters.

The Fort Myers Regional Library replaces the Fort Myers-Lee County Public Library located at 2050 Central Avenue, Fort Myers, FL 33901, which was once home to Lorelei, a white marble sculpture that dates back to circa 1880 which the library chose to leave behind when it moved to its new quarters.- Marks & Brands is the second commission issued by the Fort Myers Public Art Committee since its inception in 2004. (The first was Fire Dance by Ohio proto-architectural monumental artist David Black.)

- Stacked Brands was installed on Saturday, November 16, 2013.

- Peter Mitten oversaw the installation process and attended the dedication ceremony for Stacked Brands.

September 3, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.