Cultural Park’s ‘Golden Pond’ remarkably crafted character study

On stage for a final weekend at Cultural Park Theatre is Ernest Thompson’s On Golden Pond. It’s a remarkably crafted character study thanks in large measure not only to Ernest Thompson’s script, but to Gwen Salata’s direction and the amazingly capable performances rendered by her entire cast.

On stage for a final weekend at Cultural Park Theatre is Ernest Thompson’s On Golden Pond. It’s a remarkably crafted character study thanks in large measure not only to Ernest Thompson’s script, but to Gwen Salata’s direction and the amazingly capable performances rendered by her entire cast.

On Golden Pond was  originally written for the stage. First performed in 1979, it earned two Tony nominations, including one for Frances Sternhagen as Norman’s wife Ethel, the Oscar-winning role played by Katherine Hepburn in the movie. The show was again produced on Broadway in 2005. This time, James Earl Jones played Norman Thayer; Leslie Uggams played Ethel. Jones earned a Tony nomination as did the play for Best Revival.

originally written for the stage. First performed in 1979, it earned two Tony nominations, including one for Frances Sternhagen as Norman’s wife Ethel, the Oscar-winning role played by Katherine Hepburn in the movie. The show was again produced on Broadway in 2005. This time, James Earl Jones played Norman Thayer; Leslie Uggams played Ethel. Jones earned a Tony nomination as did the play for Best Revival.

Cultural Park’s iteration is a creature of its own. Oh, it’s still a love story between Norman and Ethel, but there is a lot more going on. Both Norman and Ethel are grappling with the early stages of his dementia and chronic congestive heart failure. And with time running out, it’s more important than ever for Norman to patch up his relationship with  his estranged daughter Chelsea.

his estranged daughter Chelsea.

Greg Wojciechowski plays Norman, a sardonic glass-half-empty college professor on the verge of turning 80. Salata and Wojciechowski are both cognizant of and embrace the irony implicit in Norman’s situation. As a younger and even middle-age man, Norman has always possessed an intellect far superior to those around him, including his wife and daughter. He has exacting standards, particularly where Chelsea was concerned.  But as a Mensa-level Brainiac, he also enjoys playing mind games with people for his own perverse amusement. Because his sense of humor is as dry as a Valpolicella Chianti and just as acerbic, he generally comes off as an intolerant bastard. If you try to be agreeable, he’ll walk all over you. So the only way you can earn his respect is by tossing back the bull he’s shoveling out.

But as a Mensa-level Brainiac, he also enjoys playing mind games with people for his own perverse amusement. Because his sense of humor is as dry as a Valpolicella Chianti and just as acerbic, he generally comes off as an intolerant bastard. If you try to be agreeable, he’ll walk all over you. So the only way you can earn his respect is by tossing back the bull he’s shoveling out.

Billy  Ray does this from their very first meeting and, as a result, they forge an immediate bond.

Ray does this from their very first meeting and, as a result, they forge an immediate bond.

By contrast, Chelsea never has.

To complicate matters, Norman has used his dry wit not only to tease her, but as a prod. That combination has proven deleterious over time not only to their relationship, but to his daughter’s ego and self-esteem. It’s probably fair to say that she’d have nothing to do with the old bird if it weren’t for her mother.

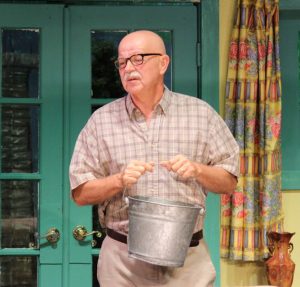

Now Norman is  slipping cognitively as well as physically, and he’s frightened to his very core. This is aptly illustrated by a brief scene in the play where he returns from a berry-picking assignment that Ethel has given him with an empty pail because he couldn’t remember where to go when he got to the end of the walkway in front of the cottage.

slipping cognitively as well as physically, and he’s frightened to his very core. This is aptly illustrated by a brief scene in the play where he returns from a berry-picking assignment that Ethel has given him with an empty pail because he couldn’t remember where to go when he got to the end of the walkway in front of the cottage.

At this juncture, you might (justifiably) be thinking that Norman’s such a poop (that’s Ethel’s word of endearment for him), why should we care what happens to him. But Norman has a number of redeeming qualities. He genuinely loves his wife, considers himself lucky that she loves him in return, and if you can just get past his barbs and quills, he’s actually incongruously sentimental.

At this juncture, you might (justifiably) be thinking that Norman’s such a poop (that’s Ethel’s word of endearment for him), why should we care what happens to him. But Norman has a number of redeeming qualities. He genuinely loves his wife, considers himself lucky that she loves him in return, and if you can just get past his barbs and quills, he’s actually incongruously sentimental.

Clearly, Norman  Thayer is a complex, nuanced character. Wojciechowski plays him exceptionally well. He doesn’t just make the abrasive curmudgeon lovable at the appropriate times, he actually elicits sympathy, if not empathy, from the audience as he grapples with the increasing erosion of his mental acuity and desperately resorts to only partially

Thayer is a complex, nuanced character. Wojciechowski plays him exceptionally well. He doesn’t just make the abrasive curmudgeon lovable at the appropriate times, he actually elicits sympathy, if not empathy, from the audience as he grapples with the increasing erosion of his mental acuity and desperately resorts to only partially  successful strategies intended to keep his wife, daughter and even the mailman from realizing the extent of his growing cognitive deficits.

successful strategies intended to keep his wife, daughter and even the mailman from realizing the extent of his growing cognitive deficits.

But for as good as Wojciechowski is in this production, On Golden Pond is Gerrie Benzing’s show. Her performance is an informed, insightful and fundamentally organic study of love, understanding and acceptance.

Under  Salata’s direction, Benzing leaves no question about the depth and duration of her love for Norman. In spite of his many flaws and failings, she adores her husband even after the passage of decades and his unceremonious entry into the sunset of his life. It’s not that she doesn’t see his foibles. It’s not that she makes allowances for them. She loves him notwithstanding their existence.

Salata’s direction, Benzing leaves no question about the depth and duration of her love for Norman. In spite of his many flaws and failings, she adores her husband even after the passage of decades and his unceremonious entry into the sunset of his life. It’s not that she doesn’t see his foibles. It’s not that she makes allowances for them. She loves him notwithstanding their existence.  She gets that he is and has always been a man torn unable to reconcile his mental and emotional lives.

She gets that he is and has always been a man torn unable to reconcile his mental and emotional lives.

And therein lies a key to understanding Salata and Benzing’s Ethel Thayer. She’s a realist. Perhaps even something of a fatalist. Rather than deny, become angry or withdraw in the face of her husband’s growing dementia, she accepts him and the condition with grace and equanimity. Rather than criticize him for what he doesn’t do, she celebrates the small things he  is still able to accomplish. Sure, that places a greater physical and emotional burden on her, but that’s just the way it is.

is still able to accomplish. Sure, that places a greater physical and emotional burden on her, but that’s just the way it is.

The berry gathering incident mentioned earlier is a case in point. Ethel doesn’t chide Norman for coming back with an empty pail. Nor does she dismiss his fears  as silly or irrational. Instead, she acknowledges their validity and provides him the comfort of her embrace. Drawing, no doubt, on her experience raising five children, Benzing brings a palatable degree of patience and tenderness to this scene.

as silly or irrational. Instead, she acknowledges their validity and provides him the comfort of her embrace. Drawing, no doubt, on her experience raising five children, Benzing brings a palatable degree of patience and tenderness to this scene.

While Ernest Thompson’s prescient script admittedly controls the action and character development over the course of the play, through her portrayal Benzing deftly draws out several life lessons that give direction and solace to the 16 million  American spouses and other family members who are caring for someone with dementia. She becomes lovingly exasperated (“you poop”) without giving in to frustration. She keeps her communications with Norman short, simple and clear. She gets in his face, makes eye contact and uses gestures and touch to get his attention. And she makes sure that Norman gets plenty of sensory stimulation

American spouses and other family members who are caring for someone with dementia. She becomes lovingly exasperated (“you poop”) without giving in to frustration. She keeps her communications with Norman short, simple and clear. She gets in his face, makes eye contact and uses gestures and touch to get his attention. And she makes sure that Norman gets plenty of sensory stimulation  and socialization.

and socialization.

That’s one reason she continually invites Charlie Martin (the mailman, played by Curtis Deterding) inside for coffee and muffins.

It’s also one of the reasons she persuades Norman to allow Billy Ray to stay with them for a month while Chelsea and his father vacation in Europe. Oh, she  couches the idea as a conciliatory gesture toward Chelsea, but it’s apparent that the boy’s presence in the cottage provides Norman with a level of mental stimulation and physical activity she’s not prepared or equipped to provide. Plus, it gives her a much needed respite from doting on her husband while discharging a laundry list of daily chores.

couches the idea as a conciliatory gesture toward Chelsea, but it’s apparent that the boy’s presence in the cottage provides Norman with a level of mental stimulation and physical activity she’s not prepared or equipped to provide. Plus, it gives her a much needed respite from doting on her husband while discharging a laundry list of daily chores.

Today, someone in Ethel’s shoes would undoubtedly do copious research into how to care for a spouse facing physical and cognitive degeneration, and perhaps Benzing did in order to better understand her character and what she was up against. Whether it was careful character analysis, painstaking research, insightful direction or profound insights emanating from her own life experiences, Benzing’s performance is to be applauded and remembered for its natural, organic quality. She does

Today, someone in Ethel’s shoes would undoubtedly do copious research into how to care for a spouse facing physical and cognitive degeneration, and perhaps Benzing did in order to better understand her character and what she was up against. Whether it was careful character analysis, painstaking research, insightful direction or profound insights emanating from her own life experiences, Benzing’s performance is to be applauded and remembered for its natural, organic quality. She does  what she does not because some book, pamphlet or doctor told her to, but as an expression of love. It’s what Norman needs at this time in his life, and she provides it because she loves him. It’s as simple as that. [Query whether you could muster the same love, understanding and grace under fire that Ethel displays at Gerrie Benzing’s conjuring.]

what she does not because some book, pamphlet or doctor told her to, but as an expression of love. It’s what Norman needs at this time in his life, and she provides it because she loves him. It’s as simple as that. [Query whether you could muster the same love, understanding and grace under fire that Ethel displays at Gerrie Benzing’s conjuring.]

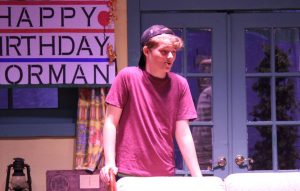

The supporting  cast is also deserving of recognition and praise. Cassie Sampson, Curtis Deterding, Nikolas Beyor and Edward Smith each make invaluable contributions to the story and overall production. Deterding is immensely enjoyable as the cheerfully simplistic mail carrier Charlie Martin and Sampson captures the essence of that tortured child who has always yearned for, but never won, the love and acceptance of a demanding, overbearing

cast is also deserving of recognition and praise. Cassie Sampson, Curtis Deterding, Nikolas Beyor and Edward Smith each make invaluable contributions to the story and overall production. Deterding is immensely enjoyable as the cheerfully simplistic mail carrier Charlie Martin and Sampson captures the essence of that tortured child who has always yearned for, but never won, the love and acceptance of a demanding, overbearing and emotionally unavailable parent.

and emotionally unavailable parent.

It also bears mentioning that the set in this production also functions as a supporting character. Attention has been paid to even the smallest of details in the successful effort to recreate the Thayers’ summer cottage on Golden Pond in Maine.

On Golden Pond closes with Sunday’s matinee.

October 30, 2019.

RELATED POSTS.

Cultural Park’s ‘On Golden Pond’ illustrates life’s hilarious, heartbreaking human moments

Cultural Park’s ‘On Golden Pond’ illustrates life’s hilarious, heartbreaking human moments- ‘On Golden Pond’ play dates, times and ticket info

- Spotlight on ‘Golden Pond’ actor Gerrie Benzing

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.