Ghostbird’s ‘Catastrophe’ invites us to look at ourselves and the powers that control us

Ghostbird Theatre Company has built a reputation over the last handful of years for edgy, thought-provoking nontraditional theater presentations, and it did not disappoint the enlightened Art Walkers who made the three block trek from the cordoned-off section of First Street May 4 to the Langford-Kingston Home where they enjoyed not one, but two short-yet-provocative plays, Samuel Beckett’s Catastrophe and Barry Cavin’s Ibb.

Ghostbird Theatre Company has built a reputation over the last handful of years for edgy, thought-provoking nontraditional theater presentations, and it did not disappoint the enlightened Art Walkers who made the three block trek from the cordoned-off section of First Street May 4 to the Langford-Kingston Home where they enjoyed not one, but two short-yet-provocative plays, Samuel Beckett’s Catastrophe and Barry Cavin’s Ibb.

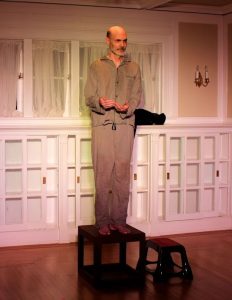

Catastrophe opened with a pajama-clad actor standing motionless on a plinth toward the far end of the parlor of the grand Langford-Kingston Home. Enter an impatient, obnoxiously officious Director (Dana Lynn  Raulerson) and her Assistant (Katelyn Gravel), who undertake final preparations for a stage presentation that will consist entirely of the unspeaking man silently regarding the audience from his perch on the unadorned pedestal. The Assistant has pre-arranged certain aspects of the man’s position and attire, and must now justify her artistic decisions to the imperious, self-important Director. It is left to the audience to decide what to make of the interactions between the Director, her Assistant and the Actor and the message(s) that Beckett intended to convey by his clearly metaphorical depictions.

Raulerson) and her Assistant (Katelyn Gravel), who undertake final preparations for a stage presentation that will consist entirely of the unspeaking man silently regarding the audience from his perch on the unadorned pedestal. The Assistant has pre-arranged certain aspects of the man’s position and attire, and must now justify her artistic decisions to the imperious, self-important Director. It is left to the audience to decide what to make of the interactions between the Director, her Assistant and the Actor and the message(s) that Beckett intended to convey by his clearly metaphorical depictions.

The play premiered at the Avignon Festival in 1982. Originally written in French, Catastrophe has been described as Beckett’s most overtly political play. Throughout his life, Beckett took political positions. He was against oppression. He supported individualism. And he opposed all forms of totalitarianism and fascism. But like many upper-echelon artists, Beckett also felt deeply that within the realm of art, themes were to be suggested rather than stated.

The play premiered at the Avignon Festival in 1982. Originally written in French, Catastrophe has been described as Beckett’s most overtly political play. Throughout his life, Beckett took political positions. He was against oppression. He supported individualism. And he opposed all forms of totalitarianism and fascism. But like many upper-echelon artists, Beckett also felt deeply that within the realm of art, themes were to be suggested rather than stated.  If playwrights or visual artists got too explicit, they risked undermining what they were attempting to convey.

If playwrights or visual artists got too explicit, they risked undermining what they were attempting to convey.

Within this context, Director Barry Cavin’s casting choices prove somewhat definitive of the conclusions the audience might draw from Ghostbird’s production of the play. Because Beckett wrote Catastrophe for and dedicated it to a playwright who’d been imprisoned by Czech authorities for his political views, many interpret the play as somber commentary on the ways in  which authoritarian political figures seek to control the common man by stripping him of his humanity. But had that been Cavin’s interpretation of the play, he would have cast Brock in the role of the Director and the diminutive Hanny Zuniga as the actor. Ghostbird audiences are still talking about Brock’s portrayal of the maniacal Dr. Cyrus Teed in Cavin’s ORBS! earlier this year, and Zuniga demonstrated her stoicism as Ghostbird’s “ring girl” as she held up a

which authoritarian political figures seek to control the common man by stripping him of his humanity. But had that been Cavin’s interpretation of the play, he would have cast Brock in the role of the Director and the diminutive Hanny Zuniga as the actor. Ghostbird audiences are still talking about Brock’s portrayal of the maniacal Dr. Cyrus Teed in Cavin’s ORBS! earlier this year, and Zuniga demonstrated her stoicism as Ghostbird’s “ring girl” as she held up a  handwritten “Intermission” sign between Catastrophe and Ibb.

handwritten “Intermission” sign between Catastrophe and Ibb.

But no, by placing Brock on the plinth and constituting Raulerson as his tyrannical director, Cavin resisted the easy casting call. In so doing, he opened Ghostbird’s rendition of Catastrophe to a far greater number of metaphorical interpretations.

On one level, Catastrophe could simply symbolize the forces employed by museum and gallery directors worldwide to define, limit and control the visual artists they exhibit to the general public.

It is equally plausible that in Cavin’s hands, Catastrophe satirizes politicians who seek to quash artistic expression by cutting their funding, as seen recently in Florida as lawmakers in Tallahassee slashed spending for the arts from $43 million in 2014 to just $2.6 million for coming year to be split by 489 cultural organizations.

It is equally plausible that in Cavin’s hands, Catastrophe satirizes politicians who seek to quash artistic expression by cutting their funding, as seen recently in Florida as lawmakers in Tallahassee slashed spending for the arts from $43 million in 2014 to just $2.6 million for coming year to be split by 489 cultural organizations.

On another plane, the play can be viewed as a psychological construct, with the Director, Assistant and Protagonist being embodiments of Freud’s Super-Ego, Ego and Id. From this vantage, the import  of the play is not condemnation of how totalitarian regimes or authority figures seek to manipulate or control Everyman, but rather a scathing criticism of Everyman’s mute acceptance of his own subjugation.

of the play is not condemnation of how totalitarian regimes or authority figures seek to manipulate or control Everyman, but rather a scathing criticism of Everyman’s mute acceptance of his own subjugation.

And that’s the beauty of Cavin’s casting.

Those who saw Catastrophe on May 4 were free to assign whatever meaning they liked to the play. And that, of course, is the mission of all good theater. At their best, plays operate as a vehicle for introspection and conversation by and among those who take the time to attend them.

All three  actors deserve special recognition. Brock is to be commended for the stoicism he exhibited as Gravel’s Assistant postured and primped his character, who was dressed in little more than nondescript gray pajamas. Raulerson was chilling as the loud, mean-spirited Director. It was more than a little humorous to watch audience members recoil and shift uncomfortably in their seats each time Raulerson barked out orders to her Assistant or chastised her for not correctly intuiting her desires or carrying out her instructions as quickly as she expected.

actors deserve special recognition. Brock is to be commended for the stoicism he exhibited as Gravel’s Assistant postured and primped his character, who was dressed in little more than nondescript gray pajamas. Raulerson was chilling as the loud, mean-spirited Director. It was more than a little humorous to watch audience members recoil and shift uncomfortably in their seats each time Raulerson barked out orders to her Assistant or chastised her for not correctly intuiting her desires or carrying out her instructions as quickly as she expected.

Although Beckett clearly meant for the audience to feel sorry for the plight of the  Protagonist, in this particular production, Katelyn Gravel’s Assistant turned out to be the more sympathetic of the two characters. Perhaps that’s because Brock stoically endured what she and the Director were doing to him. Or perhaps it was because as an actor, he’d willingly given himself over to their manipulation and control. But poor Katelyn! There was just no pleasing her boss, and who among us can’t identify with that! Make a note of it.

Protagonist, in this particular production, Katelyn Gravel’s Assistant turned out to be the more sympathetic of the two characters. Perhaps that’s because Brock stoically endured what she and the Director were doing to him. Or perhaps it was because as an actor, he’d willingly given himself over to their manipulation and control. But poor Katelyn! There was just no pleasing her boss, and who among us can’t identify with that! Make a note of it.

If you were not looking for it, you could have very easily missed the poignant ending to this play. It’s a simple, almost  imperceptible act or resistance. At the Director’s instruction, her Assistant has angled the Protagonist’s head down, facing the floor. After the Director and Assistant are finished staging his posture and attitude, the Protagonist raises his head to stare directly into the eyes of the audience. At the time the play premiered, some critics described this ending as ambiguous. But Beckett vehemently disagreed. “It’s not ambiguous,” the playwright maintained. “He’s saying,

imperceptible act or resistance. At the Director’s instruction, her Assistant has angled the Protagonist’s head down, facing the floor. After the Director and Assistant are finished staging his posture and attitude, the Protagonist raises his head to stare directly into the eyes of the audience. At the time the play premiered, some critics described this ending as ambiguous. But Beckett vehemently disagreed. “It’s not ambiguous,” the playwright maintained. “He’s saying,  ‘You bastards, you haven’t finished me yet!'”

‘You bastards, you haven’t finished me yet!'”

In effect, by that one simple act Beckett is proclaiming that no matter how much politicians, social structure or religion strive to reduce people to mindless, mechanized objects, the human spirit won’t be so confined. People are resilient and persistent. They will only submit for so long. Ultimately, people will rise above and overcome  their oppressors – even if it takes a lifetime or many lifetimes as history has repeatedly witnessed.

their oppressors – even if it takes a lifetime or many lifetimes as history has repeatedly witnessed.

But all change starts at the individual level. And perhaps that is the overarching message of Ghostbird’s performance of Beckett’s timeless classic. By choosing the cast that he did for this play, Cavin is asking, nay, demanding that each of us look more closely at ourselves and the powers that control us.

May 6, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.