Art may give children in border detention camps strength to overcome

Ela Weissberger was interned in Theresienstadt as a child. While there, a Bauhaus-trained artist by the name of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis took Ela and the other children in the ghetto under her wing, teaching them how to process and express the trauma of their experiences through art.

Ela Weissberger was interned in Theresienstadt as a child. While there, a Bauhaus-trained artist by the name of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis took Ela and the other children in the ghetto under her wing, teaching them how to process and express the trauma of their experiences through art.

Before she was ultimately murdered, Dicker-Brandeis saved thousands of the kids’ drawings and poems in suitcases. Recovered after the war, many of them are now on display at the Ghetto  Museum in Terezin.

Museum in Terezin.

It was a poem written by one of the children of Theresienstadt that inspired a grassroots global initiative in 2006 that has come to be known as The Butterfly Project. The project is the brainchild of Jan Landau, who was looking for a way to teach children about the Holocaust in a way that would be engaging but not frightening. A teacher at the San Diego Jewish Academy, Landau was familiar with a poem  titled “The Butterfly” that had been penned by a boy named Pavel Friedmann before he was deported and gassed at Auschwitz. Landau wanted to use the butterfly to symbolize the children who, like Friedmann, had perished during Shoah. In fact, she envisioned having school children around the world make a butterfly for each of the 1.5 million children who were murdered

titled “The Butterfly” that had been penned by a boy named Pavel Friedmann before he was deported and gassed at Auschwitz. Landau wanted to use the butterfly to symbolize the children who, like Friedmann, had perished during Shoah. In fact, she envisioned having school children around the world make a butterfly for each of the 1.5 million children who were murdered  during the Holocaust.

during the Holocaust.

But first, Landau needed to come up with a model she could use. The San Diego Jewish Academy happened to have an artist in residence, so Landau approached Cheryl Rattner Price with her idea. A trained ceramic artist, Price suggested making clay butterflies  that could be hand painted. So that other schools in San Diego, California, the United States and around the world could participate in the project, Landau and Price also developed kits that not only contained clay butterflies and paint, but brief stories of the children whom the butterflies

that could be hand painted. So that other schools in San Diego, California, the United States and around the world could participate in the project, Landau and Price also developed kits that not only contained clay butterflies and paint, but brief stories of the children whom the butterflies  would memorialize.

would memorialize.

“I fell in love with the project because it touched something deep inside me that I didn’t even know would wake up a sense of responsibility for the Jewish people,” Price told journalist Bracha Schwartz in an interview for Jewish Link of New Jersey. “I felt if I could be moved to learn more about the Holocaust—a topic that I had totally avoided—through making art, then others might be moved also. It really became an obsession for me. I simply felt a responsibility to keep it alive.”

in an interview for Jewish Link of New Jersey. “I felt if I could be moved to learn more about the Holocaust—a topic that I had totally avoided—through making art, then others might be moved also. It really became an obsession for me. I simply felt a responsibility to keep it alive.”

Some ten years later,  the art project morphed into a documentary, which Price wrote and co-produced with Joe Fab under the titled Not the Last Butterfly, which was shown by the Fort Myers Film Festival in 2018. Fab had done an award-winning film about a Tennessee school that collected six million paper clips to memorialize the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust, so The Butterfly Project was a natural fit.

the art project morphed into a documentary, which Price wrote and co-produced with Joe Fab under the titled Not the Last Butterfly, which was shown by the Fort Myers Film Festival in 2018. Fab had done an award-winning film about a Tennessee school that collected six million paper clips to memorialize the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust, so The Butterfly Project was a natural fit.

For the film, they decided to marry the ceramic butterfly project with the stories of Ela Weissberger and Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. Weissberger even agreed to travel back to Terezin with Price and Fab and talk about her childhood in the camp. But the film’s focus remains on The Butterfly Project which, as of the film’s release, had resulted in the installation of more than 150,000 ceramic butterflies in nearly a dozen countries

For the film, they decided to marry the ceramic butterfly project with the stories of Ela Weissberger and Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. Weissberger even agreed to travel back to Terezin with Price and Fab and talk about her childhood in the camp. But the film’s focus remains on The Butterfly Project which, as of the film’s release, had resulted in the installation of more than 150,000 ceramic butterflies in nearly a dozen countries  worldwide.

worldwide.

And so as it was in Theresienstadt 66 years ago, art has the power to enable those who make and connect with it endure and overcome even the darkest tragedies. The stories of Ela Weissberger and The Butterfly Project are both testaments to the incredible resiliency of the children and the strength and endurance of the human spirit.

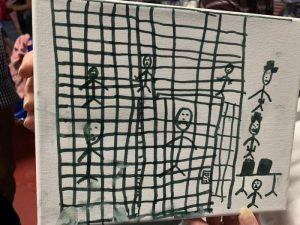

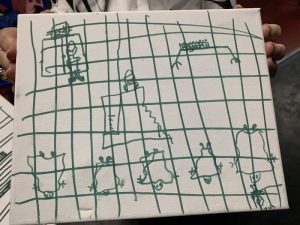

Like it or not, but parallels can be drawn to the conditions being experienced at present in the border detention camps housing migrant children and those existing in Theresienstadt more than six decades ago. And as then, art is again being used to help the children who have been released to process the sights, sounds, smells and emotions they experienced during their time in U.S. Customs and Border Protection

it or not, but parallels can be drawn to the conditions being experienced at present in the border detention camps housing migrant children and those existing in Theresienstadt more than six decades ago. And as then, art is again being used to help the children who have been released to process the sights, sounds, smells and emotions they experienced during their time in U.S. Customs and Border Protection  custody.

custody.

So as we are congratulating ourselves on the ideals and durability of the experiment in democracy that we call the Unites States of America, perhaps we should pause to consider the morality of our treatment of these children and whether on our behalf our representatives are guilty of child neglect and abuse. And I further challenge our area artists to come up with a symbol like the butterfly that might enable all Americans, regardless of political party or persuasion, to rally to their defense and advocate for their humane treatment.

July 3, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.