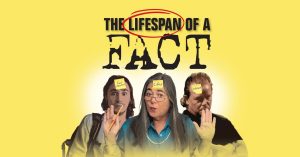

With ‘Lifespan of a Fact,’ Players Circle jumps into the fray of the fake news, alternative facts debate

In an interview he gave The New Yorker several weeks ago, filmmaker Morgan Neville remarked that that he had blended AI-generated voiceovers with clips from Anthony Bourdain’s television shows, radio and podcast appearances, and audiobooks in his documentary about the late travel-chef titled Roadrunner.

In an interview he gave The New Yorker several weeks ago, filmmaker Morgan Neville remarked that that he had blended AI-generated voiceovers with clips from Anthony Bourdain’s television shows, radio and podcast appearances, and audiobooks in his documentary about the late travel-chef titled Roadrunner.  The disclosure triggered a debate among documentarians and film critics about the ethics of employing “expansive storytelling techniques” in order to dramatize a seemingly fact-based biopic. Indeed, we are all buffeted with a constant stream of “fake news,” “alternative facts” and manipulative algorithms in the content we view in media outlets ranging from broadcast and cable news to social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. And with its upcoming production of Lifespan of a Fact, Players Circle Theatre jumps into the fray with this dramedy based on the true story of John D’Agata and Jim Fingal.

The disclosure triggered a debate among documentarians and film critics about the ethics of employing “expansive storytelling techniques” in order to dramatize a seemingly fact-based biopic. Indeed, we are all buffeted with a constant stream of “fake news,” “alternative facts” and manipulative algorithms in the content we view in media outlets ranging from broadcast and cable news to social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. And with its upcoming production of Lifespan of a Fact, Players Circle Theatre jumps into the fray with this dramedy based on the true story of John D’Agata and Jim Fingal.

A recent Harvard grad who’d majored in English, Jim Fingal took a job with one of the best magazines in the country as a fact-checker. Not long after, Fingal’s boss gave him a huge assignment – apply his skill to a groundbreaking essay written by legendary author John D’Agata which, coincidentally, had been rejected by another publication. It quickly becomes clear to Fingal why. D’Agata, he discovers, made up a lot of the information contained in the essay, and so what starts out as a professional relationship quickly becomes

A recent Harvard grad who’d majored in English, Jim Fingal took a job with one of the best magazines in the country as a fact-checker. Not long after, Fingal’s boss gave him a huge assignment – apply his skill to a groundbreaking essay written by legendary author John D’Agata which, coincidentally, had been rejected by another publication. It quickly becomes clear to Fingal why. D’Agata, he discovers, made up a lot of the information contained in the essay, and so what starts out as a professional relationship quickly becomes  profane as D’Agata and Fingal struggle to navigate the boundaries of literary nonfiction and the importance of truth in journalism.

profane as D’Agata and Fingal struggle to navigate the boundaries of literary nonfiction and the importance of truth in journalism.

“If we’ve done our job correctly,” comments Players Circle founder and director Robert Cacioppo, “a third of the audience will side with the writer, a third will side with the fact-checker and the other third will come down on the side of the publisher.”

To ensure that very result, Cacioppo has enlisted the formidable skills and immense talent of three of Southwest Florida’s top actors, Paul Graffy, Carrie Lund and Steven Coe.

Graffy is at his absolute best when he plays the temperamental, self-righteous, officious type, as he has in The Dining Room, The Crucible (where Lab Theater patrons are still haunted by his narrowed, scathing, impatient eyes in the role of Judge Thomas Danforth) and The Best Man (where he played amoral, power-hungry Senator Joe Cantwell). But he’s equally adept at displaying an unexpected sentimental side. His depth and versatility explain why he is always in high demand. Since 2001, Paul has appeared in more than 30 productions and directed over a dozen others at such theaters as The Naples Players, Artis Naples, TheatreZone, The Studio Players, The Naples Dinner Theater, the Laboratory Theater of Florida and, of course, The Players Circle.

Steven Coe is Graffy’s equal. The two faced off in The Crucible, and to a lesser degree in How to Transcend a Happy Marriage. Coe originally cut his theatrical teeth doing comedy, but of recent he has wowed area audiences with such dramatic roles as Sandro Botticelli in Botticelli in the Fire, Thomas Novacheck in Venus in Fur and Andri in Andorra. He’s best at playing the put-upon, under-fire character who refuses to be anyone’s victim, so he seems perfectly suited to the role of Jim Fingal.

Carrie Lund’s on-stage career spans more than 35 years. She has performed regionally in theaters in New York, Vermont, Pennsylvania and North Carolina. In Southwest Florida, Carrie has starred in more than 100 productions. As a member of the Actor’s Equity Association, she acted 451 weeks over 21 years. In Florida Rep’’ 19th season, she acted in the one-woman show Erma Bombeck, At Wit’s End, and all nine Wall Street Journal reviewed shows. Some of her favorite credits include Private Lives, Talley’s Folly, August Osage County, God of Carnage and Becky’s New Car. She was named Best Actress by Florida Weekly in 2011. She’s a force in any role and every production.

And so it falls upon these three awesome actors to highlight the play’s dramatic theme, the interplay between truth and storytelling when it comes to journalism and, derivatively, theater, literature and filmmaking.

While accusations of fake news and alternative facts may be recent and highly-publicized developments, the debate is not new. For example, playwright Jordan Tannahill took extensive liberties with historical fact and yet Botticelli in the Fire was touted as a recounting of the events surrounding the creation of his masterpiece The Birth of Venus and the Bonfire of the Vanities. Over at the Alliance for the Arts, Theatre Conspiracy will soon be poking fun at history with its gender-bending production of Men on Boats, in which playwright Jacklyn Backhaus recounts the exploration of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon in the summer of 1869 by ten intrepid pioneers led by one-armed Civil War vet John Wesley Powell with an all-female cast. Authors Dan Brown, Steve Berry and James Rollins have amassed fortunes pioneering the genre of “historical” fiction with works like The DaVinci Code, The Amber Room and Sandstorm. But it is the realm of documentary filmmaking that finds itself falling under considerable scrutiny these days – perhaps because documentarians purport to be presenting factual narratives about the people and events that become the subject of their exposes.

In reality, most (perhaps all) documentary filmmakers discount, distort and ignore key facts in aid of more cohesive, fluent and compelling storytelling. This is not new. Nanook of the North is a case in point. When Robert Flaherty lensed the documentary in 1922, he staged most of the scenes he included in the film, changed his subject’s name from Allakariallak to Nanook because the former was impossible for American audiences to pronounce, and substituted a prettier Inuit woman for Nanook’s plain-bordering-on-severe real-life wife. Yet, these adaptations were never revealed to the audiences who viewed the film.

How far can – or should – filmmakers go in sacrificing historical and factual accuracy in aid of storytelling? The use of AI to recreate Anthony Bourdain’s voice may seem relatively innocuous and inconsequential. But should audiences know when the subject of a documentary is paid to appear in a biopic about their life? Or the political views of a documentarian or the socio-political agenda they may be seeking to advance with their seemingly fact-based film? Is it important, for example, that Verizon financed Rory Kennedy’s documentary Without a Net: The Digital Divide in America and stands to benefit financially to the extent that broadband is expanded into the millions of classrooms in this country and huge number of children who do not currently have computers or internet access.

Lifespan of a Fact does not deal directly in these or a host of other issues in the fact-versus-fiction debate, but it certainly does by implication, and for that reason alone it is perhaps one of the timeliest plays on stage in Southwest Florida now or in the foreseeable future. The fact that it is staged in the cozy confines of Players Circle Theatre and features the likes of Graffy, Lund and Coe make this a must-see event. But space is limited and there are but 15 shows. So get your tickets early.

October 6, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.